Glencoe: Murder under Trust

Posted on 13th January 2021

On 23 April 1685, following the death of his brother Charles, James Stuart was crowned King James II of England and James VII of Scotland. Much to everyone’s relief it had been an orderly succession, the horrors of civil war still served to temper the mood of even the most adversarial, but even so James remained an avowedly Catholic King of a deeply Protestant country and suspicions remained. Nonetheless, a modicum of prudence on the part of the new Monarch might have prevented the turmoil his reign was soon to descend into.

James may not have sought to re-establish Catholicism in England, but he advocated freedom of worship and desired to see punitive measures against Catholics removed from the Statute Book which to many was much the same thing and there was no desire in England to see its people once again bend their knee to the Pope in Rome or see auto-da-fe introduced onto its streets.

On 4 April 1687, James introduced his Declaration of Indulgence also known as his Declaration of Liberty of Conscience. This was intended to remove once and for all those laws that discriminated not just against Catholics but also dissenting Protestants. It repealed the penal laws enforcing conformity to the Church of England, permitted people to worship both in chapel and hearth as they wished, and abolished the requirement to take a religious oath before being considered for employment in Government service.

In an attempt to persuade a sceptical people of the moral rectitude of his case he now embarked upon a speaking tour of the country defending its introduction with the argument: "Supposing there should be a law that all black men should be imprisoned, it would be unreasonable, and we have as little reason to quarrel with other men for being of different religious opinions as for being of different complexions."

The King was listened to respectfully even indulgently, but he was not heard.

In truth, his people were indignant, and his Declaration of Indulgence caused not only resentment but considerable discontent. Even so, his opponents were willing to tolerate it if only on the grounds of his advanced age, James was 52, quite elderly for the time, and he had not yet produced a son and heir. All this was to change however when on 10 June 1688, his beautiful Catholic wife Mary of Modena, gave birth to a healthy baby boy, James Francis Edward Stuart. The birth of a Catholic heir to the throne presented James's opponents with a dilemma that would take more than merely denying the legitimacy of the birth to resolve.

They had been in negotiations with the ruler of the Dutch Republic the Protestant Prince William of Orange for some time in the hope that should the prospect of a Catholic Dynasty, become a reality he would be willing to fill the void as the Protestant heir and usurp the throne if required. They had hoped that like the Tudor Queen Mary before him, James's Catholic rule would prove an aberration and die with him but now faced with the prospect they had most feared they were forced to act; and so on 30 June 1688, seven prominent Protestant noblemen including the Earl of Danby, the Earl of Devonshire, Viscount Lumley, and Henry Compton, the Bishop of London sent a formal invitation to William to invade England and save the country from Catholic despotism.

William of Orange, who was a cousin of James II and as a young man had spent a great deal of time at the English Court, had little desire to rule the country. His primary concern was and always would be the Dutch Republic. But he did want England as an ally in his on-going conflict with the powerful Catholic King Louis XIV of France. He wanted English troops and English resources, and he also feared that under a Catholic Monarch they might in turn become an ally of France. He responded to the request positively and on 5 November 1688, the Anniversary of the Gunpowder Plot, William landed at Brixham in Devon with 20,000 men.

At first James was determined to fight and his army was at least twice the size of William's but when learned that his leading General, John Churchill had abandoned his cause for that of his opponent he lost his nerve. Suffering from headaches and nosebleeds and unable to sleep he fled back to London where he prepared to take ship to France, but not before in a final act of pique throwing the Great Seal of England into the River Thames.

As it turned out James was captured disguised as a priest before he could make good his escape and thrown into prison but William not wanting to make a martyr of the deposed King allowed him to escape once more and make his way to the Continent.

William now set about establishing his authority in England which was to prove easier than might have been expected for someone who was in effect a foreign invader. But the people had wanted rid of James and William had also agreed to have restrictions placed upon his rule that guaranteed Parliaments position as the supreme arbiter in the country.

The settlement was agreed, if not entirely without rancour on both sides but having not descended into conflict the events of 1688 were to be celebrated as the Glorious Revolution.

This self-satisfied apple cart was upturned however when in August 1690, James arrived in Ireland with a large French Army and Irish Catholics fearing increased Protestant oppression rallied to his cause. The gates of Londonderry would be shut to him, however.

The threat to William's continued reign in England was a serious one and in response he took personal command of his Dutch/English Army and set sail for Ireland.

On 1 July 1690, he met and defeated James at the Battle of the Boyne and not for the first time James fled leaving his troops to fight and die without him. Arriving in Dublin he complained that the Irish had deserted his cause and run away. A woman in his presence reminded him that they had not run away as fast as he had as he was the first to arrive. Known thereafter as Seamus an Chaca (James the Shithead) and with his reputation in tatters he fled back to France never to return.

The victory at the Boyne had been accomplished with relative ease but William knew full well that had James not panicked it could have been very different, and the threat he posed as a rallying cry for Catholic dissent remained. As such, William was determined to root out all Catholic opposition to his rule but even though most of the country was accepting of his reign one place steadfastly displayed mixed loyalties - the Highlands of Scotland.

Scotland in the 1690's was still formally independent but the two countries had shared the same Monarch since 1603 when James VI of Scotland had also ascended to the throne of England. Now that the Stuart King had been overthrown the Scottish Parliament in Edinburgh had to decide who was to be their new Monarch.

The Scots Parliament approached the situation with circumspection and did not rush to judgement, James was their rightful King but to restore him to the throne would risk war with their more powerful neighbour.

They wrote to both Kings with due deference but the arrogant response they received from James went some way to convincing them that their best interests lay with William. After all, the majority of the country was Protestant, and the Presbyterian Kirk remained a powerful force in Scottish society. Also, cross-border trade with England was essential for the Scottish Lowland economy but this meant little in the Highlands where many thought differently.

Here the Catholic religion dominated and many feared the hegemony of Protestant Lowland Scotland and many of the Clan Chiefs had taken a personal oath of loyalty to the Stuart Monarchs, and an oath at this time was a serious matter and not easily broken; but this counted for little with the Lowland Scots who had a poor opinion of their Highland neighbours seeing them as little more than rustlers, cattle thieves and brigands. What could an oath possibly mean to them?

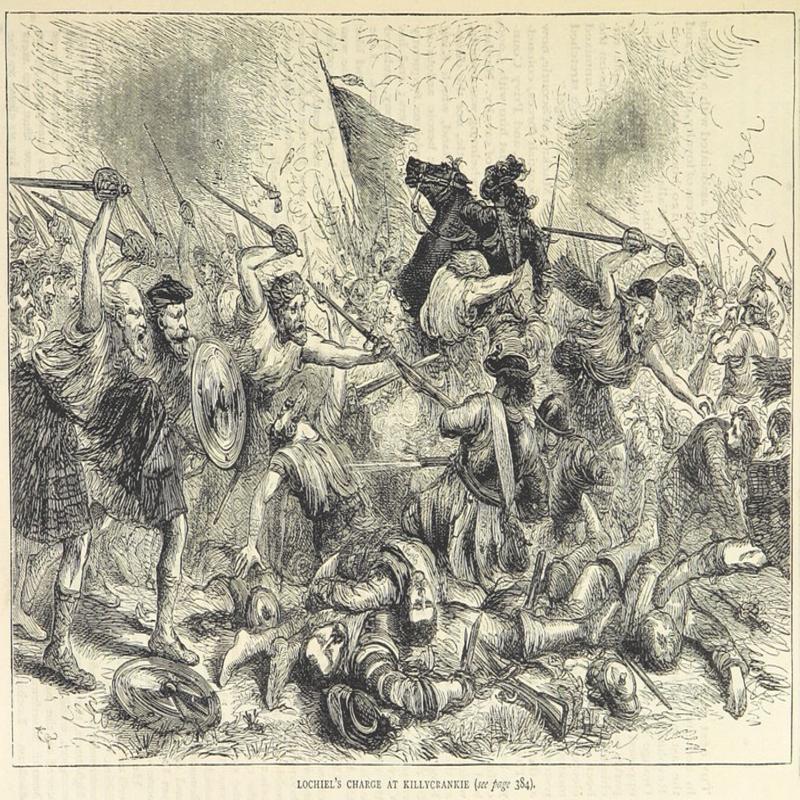

It was something worth fighting for and a series of Jacobite rebellions followed reaching their zenith at the Battle of Killiecrankie on 27 July 1689, John Graham, Viscount Dundee, defeated a much larger Lowland Covenanter Army. It was a stunning victory but a costly one and the ‘Bonnie Dundee’ had been killed in the fighting. Deprived of its leader the rebellion soon lost all direction and the Clans began to return home while others set about pillaging the surrounding countryside cementing their reputation as nothing but cutthroats and thieves. They were finally cornered and defeated on 21 August at the Battle of Dunkeld.

Escaping the battle, the MacIain's, part of the MacDonald Clan, and their Glengarry cousins on their way back to Glencoe raided the lands of Robert Campbell stealing his livestock. For Campbell who was weighed down with gambling debts the raid was a financial disaster, and he was forced to take a commission in the King's Army merely to make ends meet. But it would not be too long before Robert Campbell would have his revenge.

On 27 August 1691, William offered all those Clan Chiefs who had been involved in the uprising a pardon if they swore an Oath of Allegiance by New Year’s Day, 1692. If they refused to swear the Oath, then they would be considered still in a state of rebellion and would be dealt with accordingly.

The Clan Chiefs wrote to James, now exiled in France for permission to break their oath of allegiance to him.

James was reluctant to grant permission because he knew the loyalty of the Highland Clans remained his only hope of a future Restoration but with his cause destroyed in Ireland and with no prospect of further help from the French, he had little choice. His letter however was not received until December 1691, and his tardy response was to have tragic consequences.

Alistair MacIain, the 12th Chief of Glencoe waiting to be absolved from his Oath to James and hemmed in by bad weather did not set out for Fort William to pledge allegiance to William until 31 December, the day before it was due. Arriving just in time the Governor of Fort William Colonel Hill, told MacIain that he was not empowered to administer the Oath and that he would have to travel onto Inverary and make his supplication to Sir Colin Campbell, the Sheriff of Argyle. He did though provide the elderly Clan Chief with a letter stating that he had arrived to take the Oath within the allotted time.

The sixty-one-year-old MacIain walked the 74 miles in driving snow arriving three days later at Inverary only to find Sir Colin, due to his tardiness reluctant to administer the Oath and it was only on being shown the letter that he finally relented. The Certificate of Allegiance was signed, and he wrote a letter to Colonel Hill at Fort William:

"I endeavoured to receive the great lost sheep, Glencoe, and he has undertaken to bring in all his friends and followers as the Privy Council shall order. I am sending to order that Glencoe though he was mistaken in coming to you to take the oath of allegiance, might yet be welcome. Take care that he and his followers do not suffer till the King and the Councils pleasure be known."

Alistair MacIain returned home through severe storms feeling tired and unwell, but he had done his duty and was both satisfied and relieved that there would be no future repercussions. But unknown to him the decision had already been made to make an example of the MacDonald's at Glencoe.

The Lord Advocate of Scotland and Marshal of Stair Sir James Dalrymple, a confirmed Protestant who had an intense hatred of Highland Scots and in particular Alistair MacLain believed, as William did in London, that firm action needed to be taken should the Clans dare to contemplate rebellion in the future.

Upon receiving the certificate in Edinburgh, Dalrymple with the agreement of the other Privy Councillors present crossed MacIain’s name from it. He then sent orders to Sir Thomas Livingstone, King William’s Military Commander in Scotland:

"You are hereby ordered and authorised to march our troops which are now posted at Inverlochy and Inverness and to act against these Highland rebels who have not taken the benefit of our indemnity, by fire and sword, and all manner of hostility; to burn their houses, seize or destroy their goods or cattle, plenishings or clothes, and to cut off the men."

Along with order he also sent a private letter:

"Only just now, my Lord Argyle tells me that MacDonald of Glencoe has not taken the oath, at which I rejoice. It is a great work of charity to be exact in rooting out that damnable sect, the worst of the Highlands".

Later that same day he wrote to Colonel Hill who had first received MacIain and would be responsible for issuing the orders:

"When it comes to the time to deal with Glencoe, let it be secret and sudden. It is better not to meddle with them at all, if it cannot be done to purpose, and better to cut off that nest of robbers who have fallen foul of the law, now, when we both have the power and opportunity. When the full force of the King’s Justice is seen to come upon them, that example will be as conspicuous and as useful as his is clemency to others."

There was no ambiguity in Dalrymple’s statements and therefore could be no uncertainty as to his intentions.

Colonel Hill was appalled by the instructions he had received and voiced his concerns but to no effect. He was to delay passing the orders onto Glenlyon via the chain of command but in the end, he had little choice and in late January 1692, two companies of the Argyle Regiment, 120 men, were despatched to Glencoe under the command of the now Captain Robert Campbell of Glenlyon.

The approach of the troops concerned MacIain, who sent his son John along with 30 armed men to intercept them and discover the reason for their presence and they demanded to know why they marched on a people who had sworn an oath of loyalty to the King in England? Glenlyon reassured them that he had no aggressive intent but was merely on a mission to collect unpaid taxes but as there was no room for them at the fort any taxes due could be paid in kind by providing them with shelter.

Billeting troops had often been used as a substitute for the payment of tax but such were the rules of Highland hospitality that they would have been provided with shelter in any case and the MacDonald's made them welcome allowing them to take refuge in their homes.

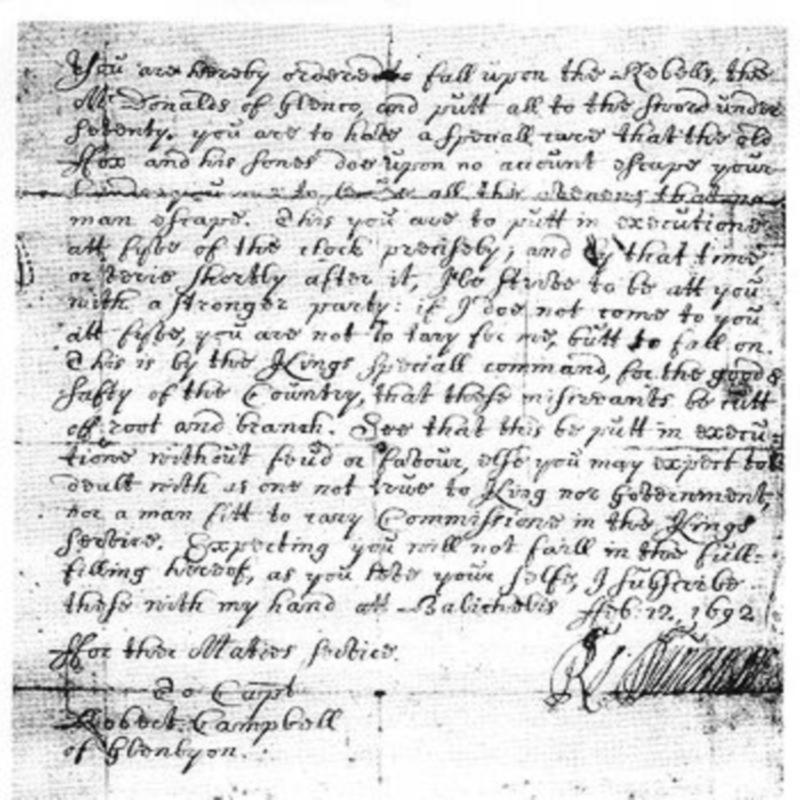

Eleven days were to pass during which the troops and the Clan sheltering from the inclement weather ate, drank, and played cards together before Robert Campbell received his orders:

"You are hereby ordered to fall upon the rebels, the MacDonald's of Glencoe, and put all to the sword under seventy. You are to have special care that the Old Fox and his sons are to die and on no account escape. All avenues are to be secured that no man escapes. You are to put into action at five in the morning."

To ensure that the events at Glencoe should remain a secret a further 400 troops were dispatched to secure all the passes out of the valley. As it turned out they arrived too late, delayed by the weather they said, though it has been suggested that they did so deliberately so that they did not have to participate in the events that were to follow.

The night that Glenlyon had received his orders he had been playing cards with his hosts and had just been invited to breakfast with the Clan Chief the following day.

On the morning of 13 February 1692, a blizzard was blowing through Glencoe and the temperature had plunged to well below freezing but despite this the massacre began at 5 am exactly the time specified and where some troops went about their business with relish others did so reluctantly.

Nine men in one billet who had overheard talk of the troops intentions the previous night and had since been kept bound, gagged, and locked up were taken outside and executed - they were some of the first to die.

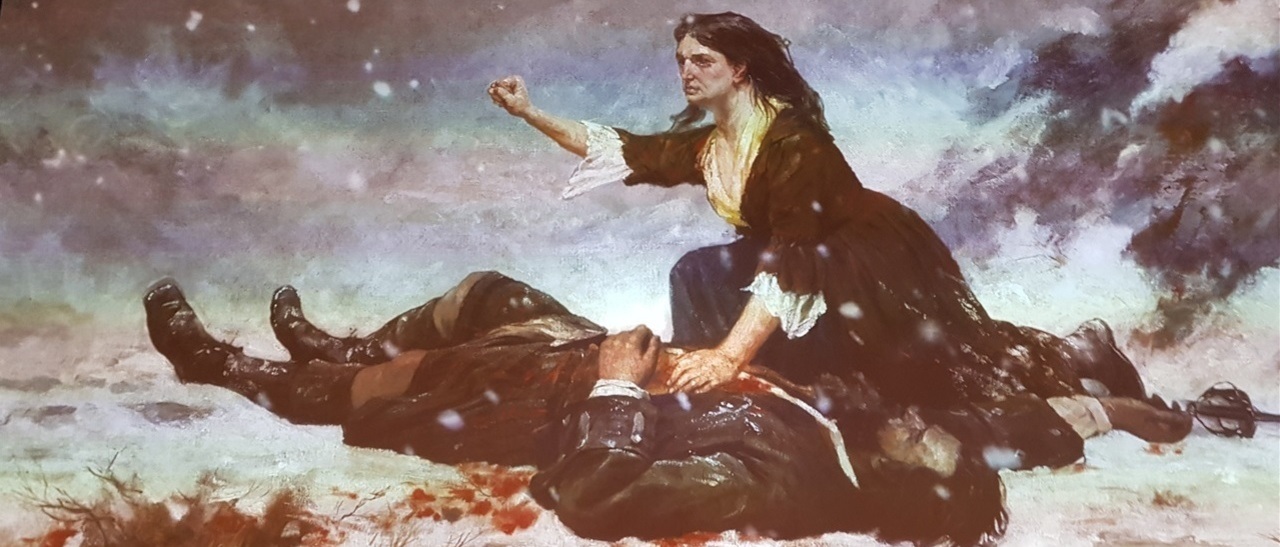

Upon hearing the commotion, the elderly Alistair MacIain began to rise from his bed but before he could do so he was shot, bludgeoned, and stabbed to death. His wife was then stripped naked, had her wedding ring ripped from her finger and was forced to flee naked into the snow.

The Clan Chief was an early target as were his sons but perhaps forewarned they managed to escape, many others were not so fortunate either killed in their beds or as they fled across the snow.

Not all the soldiers were comfortable with what they were doing, and some had indeed, much to Glenlyon’s fury, warned their hosts of what was about to occur. Others refused to participate in the massacre including Lieutenant Gilbert Kennedy and Lieutenant Francis Farquhar who broke their swords in protest rather than do so. They were to be arrested for disobeying orders but were exonerated at their subsequent Court Martial.

There were some who enjoyed their work however, the Campbell’s in particular.

When one Officer tried to prevent a Campbell from killing a child, he turned to him and said, "to save a flea is to guarantee a louse," and the child was no more.

In total 37 men, women, and children of the MacDonald Clan were killed in the initial massacre and a further 40 were to die of exposure on the mountainside in the days following, including the naked wife of the Clan Chief.

Many managed to escape because of the failure of the troops sent to block the exits from Glencoe doing so. As a result, news of the massacre soon began to spread.

The Massacre at Glencoe caused a public outcry, and many prominent voices were raised demanding that the truth be told. At the same time there was a great deal of handwringing and denials of responsibility especially in London.

King William was to deny all knowledge of the orders declaring that mixed up with his other papers he must have signed them without being aware of the contents, though this doesn’t fully explain how he managed to counter-sign them as well.

The Government in Westminster ordered an Inquiry but the fact that the orders regarding Glencoe had the King’s signature all over them a cover-up was guaranteed.

It was in the end decided that there had been no intention on the part of the Authorities to harm the MacDonald’s at Glencoe and that the resultant blood-letting was a consequence of the ancient feud that existed between Clan Campbell and Clan MacDonald despite the fact that few of the troops who participated were Campbell’s at all.

An Inquiry also took place in Scotland where there was a law on the Statute Books known as "Murder under Trust" which was considered a particularly heinous crime.

The horrific nature of the events at Glencoe even resonated with the Lowland Scots and many of their leading jurists refused to participate in the Inquiry unless there was a guarantee that punishments would be duly administered. The Scottish Parliament was in no position to punish the soldiers and servants of the King but unlike their English counterpart they declared the savage attack upon the MacDonald Clan as cold-bloodied, without pity, and condemned it as Murder under Trust.

Despite the widespread condemnation the only casualty of the Inquiry was Sir John Dalrymple who was forced to resign. Robert Campbell of Glenlyon was sent to serve in Flanders where six years later he died in poverty having never financially recovered from the earlier theft of his property.

William's desire to pacify the Highlands had succeeded in the short-term but his attempt to root out Jacobitism as a threat had failed and the sentimental loyalty that many Highlanders felt towards the Stuart cause and the old religion remained with the bitterness and resentment caused by the Massacre at Glencoe only making it more so. As a result, it would be remembered in verse and recalled in song for many years to come and would be a rallying cry for the most serious threat to Protestant rule in England the Highland Rebellion of Bonnie Prince Charlie some fifty years later.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous, Tudor & Stuart

Share this post: