Harold II: Last Saxon King of England

Posted on 6th August 2021

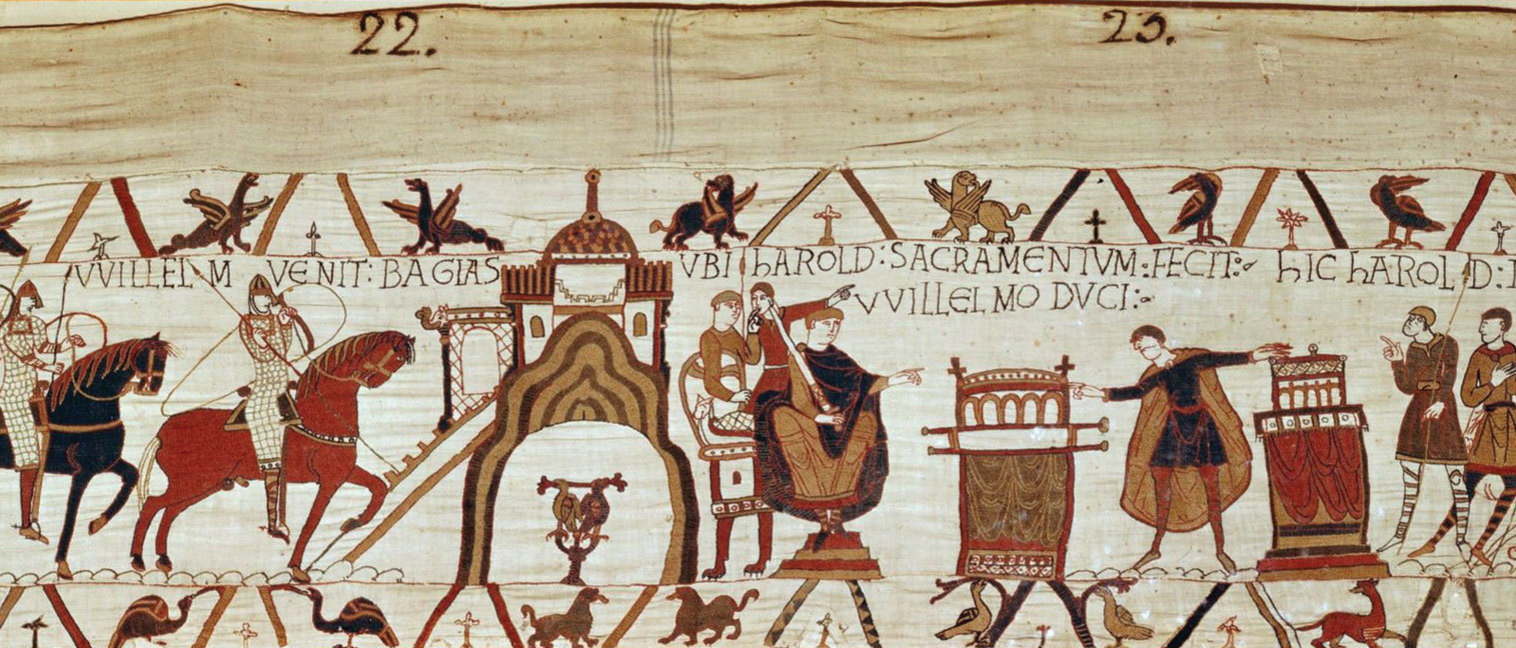

Harold Godwineson was the last Saxon King of England, a capable leader and formidable military commander, his end when it came would be immortalised in the Bayeaux Tapestry – the year was 1066 and it would change English history forever.

Harold Godwineson was born in 1022, the second son of the powerful Earl Godwineson and his wife the Viking, Gytha Thorkelsdottir.

The cunning and ruthless Godwin, who had made his fortune as a pirate, had risen to prominence as King Canute's effective right-hand man in England. When the Viking Canute died on 12 November 1035, his Anglo-Scandinavian Kingdom was split into three. His eldest son Harthacnut reigned in Denmark, Norway was governed by Magnus the Noble, whilst the Witanthe ruling Saxon Council responsible for electing the King of England prompted by Godwin supported Harold Harefoot's seizure of the Crown in England.

Harthacnut, who was no friend of his half-brother Harold, decided not to contest the succession, which at least saved Saxon England from the prospect of war.

Another man did however lay claim to the throne and he wasn't a Viking but Alfred, the son of the last Saxon King Ethelred the Unready.

He had been living in exile in Normandy along with his brother Edward but upon hearing of Canute's death he immediately laid claim to what he saw as his rightful inheritance. The Earl Godwin, as the leading member of the Witan and the most prominent Nobleman in England learning of Alfred's intentions cordially invited both Alfred and Edward to visit him at his Estate in Guildford.

Though both brothers landed in England the more circumspect Edward declined Godwin's invitation and returned to Normandy. Alfred, however, continued on his journey and was lavishly entertained by Godwin who even at one point swore an oath of loyalty and fealty to his new Lord and Master.

The same night as his guests slept after a heavy night drinking he summoned Harold Harefoot's men who butchered Alfred's entourage. Alfred himself was briefly imprisoned before he had his body mutilated and his eyes plucked out. He died three days later in Ely of his wounds.

Having displayed his loyalty and secured the throne for Harold Harefoot, Godwin revelled in the honours that were now showered upon him.

On 17 March 1040, Harold Harefoot died to be succeeded by Harthacnut who was so contemptuous of his half- brother that the first thing he did on his return was to have his body disinterred, beheaded and thrown into the River Thames.

The unmarried and childless Harthacnut now invited Edward to join the Royal Household with the intention perhaps of making him his successor. His reign would be cut short before he could do so however, when on 17 June 1042 whilst toasting the bride at a wedding reception in Lambeth, Harthacnut collapsed and died. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes how: "He died as he stood at his drink, and he fell suddenly to earth with an awful convulsion, those who were close to him took hold, but he spoke no words." A Viking end if ever there was one.

With no other obvious successor, the Witan elected Edward, already known as The Confessor for his devout piety, as King.

He may have been King, but the stability of his throne was reliant upon the continuing support of the Earl Godwin whom he held responsible for the brutal murder of his brother. He hated the Earl Godwin with a passion, but he was not in a position to do anything about it.

In 1045 at Godwin's insistence Edward married his daughter Eadgyth. I t was his intention to secure the succession for the Godwineson family and Edward though he was aware of this had little choice but to comply. He refused however to consummate the marriage.

With little support among the Saxon nobility, Edward looked to his friends in Normandy for his priests and advisers something which Godwin who was eager to promote his sons to positions of power deeply resented. They were to become bitter political opponents, but they needed each other and they knew it.

In September 1051, a violent confrontation occurred between the people of Dover and the party of Eustace II, Count of Boulogne, who was in England at Edward's invitation and in the affray several of Eustace's people were killed. The incident provided Edward with the opportunity to assert his authority and he was quick to take it.

Dover was a town in the Earl Godwin's possession and the King now ordered that he punish its people for their behaviour and their disobedience. Godwin refused, preferring to maintain the loyalty of his own Earldom. To refuse the direct order of the King was an act of treason and it allowed Edward to rally enough support to have Godwin and his family exiled abroad. Flushed with success, Edward was at last free to rule as he wished but his joy was to be short-lived and within a year The Earl Godwin was back with an army of his own and Viking support.

Edward's attempts to raise a fleet to prevent him landing failed and he was forced to restore Godwin not only to his Earldom but all his old positions of authority. It was a humiliation for Edward that was only made worse by Godwin's unbridled celebrations. He lauded over England and was now more powerful than ever.

On 15 April 1053, a little over a year after his return the 63-year-old Godwin collapsed at a banquet that was being given in his honour. He died three days later.

The outpouring of grief at the death of the Old Monster was perhaps less than sincere but then the family’s power had diminished none as the Earl Godwin's estates and authority now passed to his eldest son, Harold.

Just as ruthless as his father, Harold was at least better liked as an energetic, brave and resourceful man who despite being a Godwin quickly became indispensable to a King who preferred to reign rather than rule.

Despite being reliant upon Harold at home it seems unlikely given his hatred of the Godwin family that Edward ever considered him as his successor. Instead, he looked to Normandy where he had been born and raised for religious and political support. He spoke often of his admiration for William the Bastard the young Duke of Normandy so much so that a strong anti-Norman faction emerged at the Royal Court and within the Witan.

Edward meanwhile was spending more time than ever in isolation and pious reflection leaving the running of the country to Harold - it seemed obvious to most who was the King’s heir apparent.

In the spring of 1064, Harold was shipwrecked off the coast of Ponthieu in France. No one seems to know why he was at sea or where he was intending to go and it has since been suggested that the childless Edward who had earlier sent the Archbishop of Canterbury to Normandy to offer the succession to Duke William, had likewise sent Harold to pledge fealty.

A bedraggled and forlorn looking Harold rescued from drowning was handed over to the Duke William. The two men got on well it seems and were to spend a great deal of time in each other’s company. The Norman chronicler Orderic Vitalis wrote: "This Englishman was very tall and handsome, remarkable for his physical strength, his courage and eloquence, jests and acts of valour. But what were these gifts without honour, which is the root of all good".

It was praise and condemnation in equal measure but either way Harold impressed William who took him on campaign with him to Brittany where Harold rescued two of William's soldiers from treacherous quick sands at great danger to himself.

It was believed by some, and it most certainly was by the Normans, that whilst a guest of Duke William, Harold had sworn an oath of allegiance and fealty. The Bayeaux Tapestry certainly shows him doing this on Holy Relics, and an oath was taken very seriously indeed, to break it was to break a bond with God. The one exception was if the oath had been taken under duress.

Upon his return to England, Harold made no mention of any apparent oath and in any case he had little time to ponder upon it for he was immediately plunged into a crisis. His brother, the hot-headed Tostig to whom he was particularly close had been made Earl of Northumbria in his absence and upon taking up his new responsibility one of the first things he did was to double the rate of taxation. The only reason he could have done so was to line his own pockets and those prominent people worse affected by the measure protested to the King threatening rebellion. It was a problem that Edward was only too happy to allow the recently returned Harold to sort out.

Harold, putting aside family made the political decision to replace Tostig with the Earl Morcar. As far as Tostig was concerned to turn against your own brother was the greatest betrayal and he would never forgive Harold for doing so.

Tostig vowed vengeance and fled to Norway where he quickly formed an alliance with the ferocious and legendary Viking warrior Harald Hadrada. From now on Harold and his embittered brother Tostig would be implacable foes and it would prove fatal to both.

In January 1066, Edward the Confessor fell into a coma but despite from time to time regaining consciousness he refused to nominate a successor. On one occasion he appeared to point towards Harold, and he was said to have told his wife that upon his death Harold should succeed him as Protector of England at least, but at no point could he bring himself to name a Godwineson King.

He died on 5 January, and regardless of what he may have thought or wished the Witan selected Harold to succeed him. He was crowned at Westminster Abbey later that same day.

Hearing the news of Harold's Coronation, Duke William of Normandy flew into a rage. He was a traitor, he said, who had sworn allegiance to him as his Lord and Master on Holy Relics. He immediately began preparations to invade. But there was little enthusiasm among the Norman nobility for war. Foreign wars were expensive, and they knew that their estates would be vulnerable in their absence. It took the intervention of the Pope, who had proclaimed it a Holy War at William's request, to convince the Norman nobility to support their Lord.

In the meantime, Harold assembled his army on the Isle of Wight.

Unavailing winds delayed the sailing of William's fleet and with summer fast turning into autumn it seemed as if any invasion would have to be delayed until spring of the following year. So, on 8 September, with provisions running short Harold ordered his army to be disbanded. On the same day Tostig and Harald Hadrada who also laid claim to the throne of England landed with their forces near Newcastle.

Tostig and Hadrada quickly advanced into Yorkshire where they defeated the combined armies of Earl Morcar and Earl Edwin of Mercia in a hard-fought battle near the village of Fulford. But they were to be taken totally by surprise when just five days later on 25 September they were confronted by Harold's hastily reassembled army. Remarkably he had gathered his forces and marched them all the way from London to Stamford Bridge in Yorkshire in just four days.

Tostig and Hadrada had travelled to Stamford Bridge in order to take possession of some hostages and they had left many of their men in York. They were to find themselves outnumbered and ill-prepared to give battle and Tostig was all for retreating but Harald Hadrada never refused to give battle.

As the opposing forces lined up a man rode towards the Viking lines and shouted at Tostig that he would return to him his Earldom if he and his men would desert Hadrada. Tostig yelled back, "And what will you give, Hadrada?" To which the man replied, "As he is taller than most men, I offer him seven feet of earth".

Hadrada demanded to know of Tostig, "Who is that man?" Tostig smiled and with no little pride replied: "That is my brother Harold, King of England".

The Battle of Stamford Bridge was ferociously fought but the outcome was never in doubt and both Tostig and Hadrada were killed along with as many as 5,000 of their 6,000 men while of Hadrada's fleet of 300 ships only 24 ever returned to Norway.

Harold had little time to either celebrate his victory or mourn the death of his brother for just three days later he received the news that Duke William of Normandy had landed with his army at Pevensey Bay in Sussex. He immediately turned his army about and marched south.

Harold's army was understandably exhausted, but they were also flushed with success and their confidence was high. He could have waited for the reinforcements that were already gathering but he did not want William to establish himself inland and so despite his army being weary and only a third of the size it could have been he chose to give battle.

The decisive confrontation was to take place at Senlac Hill some six miles north of the town of Hastings.

The armies were evenly matched with both having around 12,000 men but unlike William, Harold had no cavalry so decided to take up a defensive position on the high ground behind the formidable Saxon Shield Wall.

The core of his army was made up of Housecarls, some 5,000 or so professional soldiers who were armed with a two-handed battleaxe that it was said could slice a horse in two, alongside them stood the Thegns or the Saxon nobility. The rest of his army would consist of the Fyrds, or conscripted peasants.

Duke William's army was heavily reliant upon his mounted Norman knights who were his shock troops. He also had a great many archers. His infantry were mainly drawn from conquered territories such as Bretons and Flemings along with a number of Italian mercenaries.

The battle began late in the morning of 14 October 1066, when William ordered his troops to attack uphill. Despite having the blessing of the Pope and believing that their victory was pre-ordained by God they found the going tough making little impact on the Shield Wall and suffered a great many casualties from the barrage of missiles that were hurled at them. They also came off second best in the hand-to-hand fighting as time and time again they charged and were forced back.

As the day wore on William became increasingly frantic, his troops simply couldn’t break through the shield wall so he ordered his knights to charge much earlier in the battle than would normally be the case. Yet they too were unable to penetrate the Shield Wall and as they retreated down the hill the Norman line began to falter. The Breton's on William's left flank broke and began to run taking the Flemish in their rear with them. At this pivotal moment William's horse was killed from under him and the rumour spread that he too had been killed, his army began to disintegrate.

Seeing this and believing that victory was imminent many of the Fyrd broke away from the Shield Wall and gave chase. William, who had by now found another horse, rallied his men shouting that the Shield Wall had been broken.

He managed to restore some discipline and those Saxon's who had broken ranks were surrounded and killed, among them Harold's brothers Gytha and Leofwyne who had pursued them to try and restore order.

The Saxon Shield Wall had reformed but it was now much depleted, and William now ordered his archers to fire volley after volley of arrows into the now clearly disorganised Saxon ranks. Many of the Saxon's shields had been lost or badly damaged in the fighting and they were defenceless against the rain of arrows and hundreds were killed. But still the Shield Wall held firm.

Late in the afternoon Harold, who had been in the thick of the fighting throughout was struck down by an arrow in the eye. Seeing their King dead or dying many of the Fyrd's began to flee the battlefield. The Housecarls however fought on to the bitter end.

After nearly nine hours of fighting the battle was over, Harold was dead and the Norman victory total. William ordered the usurpers body mutilated and unceremoniously buried.

It was later recovered by his wife Edith Swanneck who had it buried in secret but with great solemnity at Bosham Church near Chichester Harbour.

There would still be much hard fighting for William to do but on Christmas Day, 1066, he was crowned King William I of England at Westminster Abbey.

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval, Monarchy

Share this post: