Harriet Tubman: Mother Moses

Posted on 9th August 2021

Harriet Tubman was the ninth of eleven children, just one of the more than 4 million black people held in bondage in the Southern Slave States of America and like her fellow slaves she had no legal status and no rights but was a commodity, the property of Edward Brodess on his plantation in Dorchester County, Maryland.

Born Araminta Ross, she was a lively, playful, headstrong young girl known affectionately as ‘Minty,’ but there was little time for childhood.

Frequently separated from their parents, subject to physical chastisement, and always under the threat of being sold the children of slaves like their elders were used without recourse to anything but the whim of their owner and his or her understanding of profit and loss – so there could be no good master only a more, or less, brutal one.

Such was the life Minty was ordained to lead and so at the age of just 6 she was taken from her parents and loaned to another slave holder where she was put to work setting and clearing muskrat traps in local streams, but she soon took ill and was returned to her master.

Brodess was disappointed, a child slave could often be a burden and a sick child slave was no use at all but unlike many denied adequate medical attention Minty made a full recovery and was to be loaned out again this time as nursemaid to a white infant child.

It was easier work, at least compared to the physical demands made elsewhere but it was only temporary and by the age of 12 she was back at the plantation toiling up to sixteen hours a day in the fields as a plough hand.

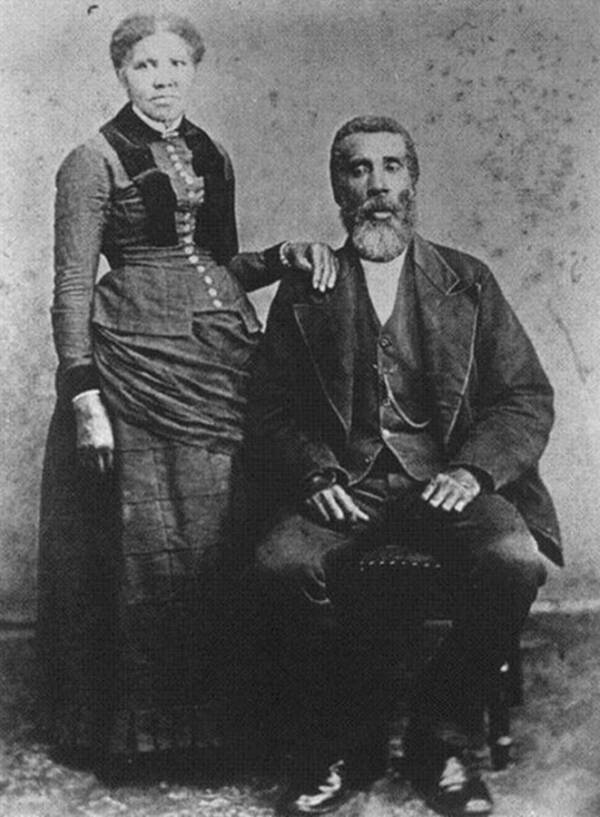

In 1844, when she was around 20 years old Minty accepted a proposal of marriage from a free black man, John Tubman but she could only marry with the permission of her master and he only reluctantly agreed once it had been established that she would remain his property and continue to work on the plantation and that any children born to her would become his property also. She also had to promise she would make no attempt to flee.

In fact, she had every intention of using her marriage as an opportunity to escape but when she told John of her intentions, he reacted angrily telling her that should she attempt do so he would report her immediately; but she would make her own decisions and in an act of what she regarded as defiance she changed her name to Harriet.

Unsurprisingly, the marriage wasn’t a success and one day she came home to find her husband had taken up with another woman and so effectively cast out she returned to the plantation.

Having tasted at least a partial freedom Harriet was to display her new-found sense of independence when she intervened to prevent a fellow slave being beaten and was struck heavily with a blunt instrument. The blow could have killed her, and she was to suffer from severe headaches and nightmares for the rest of her life – the deeply religious Harriet put the nightmares down to visions from God.

Frequently incapacitated by her injuries and increasingly recalcitrant Harriet was proving difficult and Brodess determined to sell her, but Harriet would either absent herself or feign illness whenever a prospective buyer appeared diminishing her dollar value.

In the meantime, she prayed to God that her master would change his mind – when he did not she prayed he would die. When in 1849 he did, she only regretted that she had not prayed for it earlier.

The confusion caused by Edward Brodess’s sudden and unexpected death provided Harriet with the opportunity she had been waiting for. The rumour that his widow Eliza intended to sell the slaves to chain gangs in the malarial infested swamplands of the Deep South (what was known as being sold down the river) only hastened Harriet’s decision.

On the night of 17 September 1849, Harriet and her brothers Henry and Ben fled the plantation. With no maps and little knowledge of the geography beyond the confines of the plantation other than that learned from the songs of freedom they sang in chapel and the awareness that they should follow the North Star, progress was slow, and it wasn’t long before her brothers became fearful and expressed their desire to return to the plantation in the hope that they had not been missed.

They convinced Harriet to return with them but not for long and soon fled once again saying that she would follow the North Star until freedom was reached or die in the attempt. Now alone Harriet hid in the woods during the day and travelled only at night.

The likelihood is she made use of the Underground Railroad the collective name for the route used and the series of safe houses established by white abolitionists and freed blacks to spirit escapees north.

Although the fear of capture was constant once she became aware that she had crossed the State line into Pennsylvania her sense of freedom was palpable: “When I found that I had crossed that line I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person. There was such a glory over everything, the sun came like gold through the trees, and I felt like I was in Heaven.”

But Harriet’s own successful flight to freedom was never going to be enough and she would not cease until the rest of her family were free also.

Moving to Philadelphia Harriet worked as a cook and laundress saving every cent, she could to help finance missions south to assist runaway slaves, but she could not do this on her own and so contacted the leading abolitionists in the city becoming involved in the organisation and running of the Underground Railroad. But she also demanded she be allowed to lead the missions herself.

Working out of the Wilmington home of the Quaker abolitionist Thomas Garret she led 19 successful missions south and always carrying a rifle refused to tolerate feint-heartedness threatening to shoot anyone who expressed a desire to return to the plantation and slavery.

At only 5 feet tall and with a seemingly clumsy manner Harriet had an unthreatening demeanour that served her well as did her knowledge of how to behave like a slave if approached. She also proved herself resourceful and able to adapt to every situation. She was also confident of success believing as she did that it was God’s work she was doing.

Believing she had Divine protection was one thing, but she also left nothing to chance with most of her rescue missions embarked upon in the depths of winter when the days were short and the nights long while the more inclement the weather the better. Any intended escape would also occur at the weekend when the flight would not be reported in the newspapers or elsewhere until the Monday. This provided her with the time to connect to the Underground Railroad and its well-established routes of escape.

Harriet’s success soon established her as a hero of the abolitionist movement and a scourge of the South so much so that various rewards were offered for her capture and her work already dangerous became more so with every mission successfully accomplished.

Some of her fellow abolitionists wished she would cease her activities before her luck ran out as her seizure would be a terrible blow to the cause. Their fears were almost realised when a combination of her illiteracy and the narcolepsy that was also a result of the severe beating, she had received all those years before almost resulted in her capture when she fell asleep beneath one of her own wanted posters. She barely escaped in time.

Throughout the period Harriet was active in the abolitionist movement the issue of slavery was dividing the nation as never before. Victory over Mexico in the war of 1848 and the continued expansion west had seen vast tracts of lands added to the sovereign territory of the United States and the arguments over whether these should be slave or free were intense and often violent as the south showed itself willing to fight to protect both its property and to see the spread of its peculiar institution.

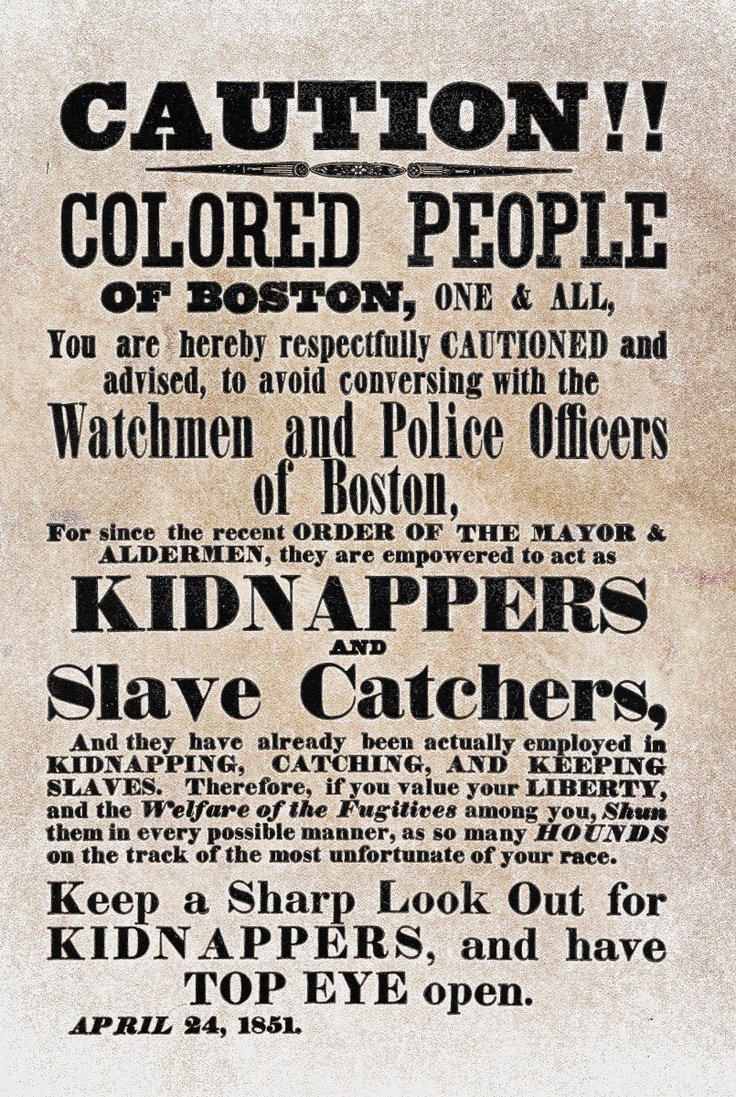

On 18 September 1850, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act which obliged every Federal Marshal and Law Enforcement Officer to arrest suspected runaway slaves. Likewise, every citizen was expected to report their suspicions and assist in the apprehension of runaways when requested to do so or face financial penalty.

Any black man or woman could be arrested as a runaway on the sworn testimony of the claimant alone. The case would not then be taken before a judge or heard in a court of law, but before specially appointed commissioners paid on a case-by-case basis with greater remuneration often attainable for the return to slavery of a suspect than those freed.

The Fugitive Slave Act instituted a reign of terror in cities where free black people had lived openly for many decades and proved a boom time for bounty hunters and unscrupulous men willing to lie to obtain ‘black property’ at little cost to themselves.

Freedom for those who had successfully escaped bondage in the south could no longer be guaranteed in the non-slave holding States of the north and the Underground Railroad now began to spirit runaways across the border into Canada.

With every black man, woman or child whether born free or not now liable to arrest or being kidnapped from the street’s abolitionists plastered the cities with posters advising them to remain at home where possible and keep their doors locked.

Harriet now had every reason to fear for her own safety, but she would neither hide nor cease her activities. Yet the Fugitive Slave Act was just the first of a series of events that were to presage slavery as the irreconcilable cancer that cursed the body politic of a nation for so long blessed by the spirit of compromise.

Slavery could either exist or it could cease to exist but as Abraham Lincoln would later say a nation could not be half slave and half free.

In March 1852, Harriet Beecher Stowe, the 40-year-old daughter of the outspoken anti-slavery Presbyterian Minister Lyman Beecher published her book Uncle Tom’s Cabin which though it may appear over-sentimental even racist to us today was nonetheless a scathing indictment of the iniquities of slavery becoming a worldwide bestseller.

But to many in the south where it was also widely read its depiction of cruel and callous slave owners brutalising those under their charge was not only indicative of their northern brethren’s attitude towards them but a direct attack upon their sense of chivalry, decency, and way of life. Indeed, it appeared to condemn them before the world.

So should the United States be a slave owning nation or not?

In January 1854, the Democratic Senator for Illinois Stephen A. Douglas passed through Congress the Kansas-Nebraska Act that would see the people of any new State decide whether it should permit slavery to exist within its borders. But his notion of popular sovereignty merely created a field of conflict as both pro and anti-slavery men flooded the territories determined to win them for their cause leading to violence which in Bleeding Kansas for example, was little short of open warfare.

On 22 May 1856, the violence even reached the floor of the Senate House when Preston Brooks, the Congressman from South Carolina beat the anti-slavery Senator for Massachusetts Charles Sumner, senseless with his cane.

Two years before pro and anti-slavery men began fighting each other in the Border States and within the hallowed halls of the Federal Legislature the Republican Party had been formed.

Made up largely of ex-Whig Party members and with a strong abolitionist element it was perceived as a direct threat particularly by the Slave States of the Deep South and its strong showing in the 1856 Presidential Election when it won 11 northern States only served to increase tensions even further.

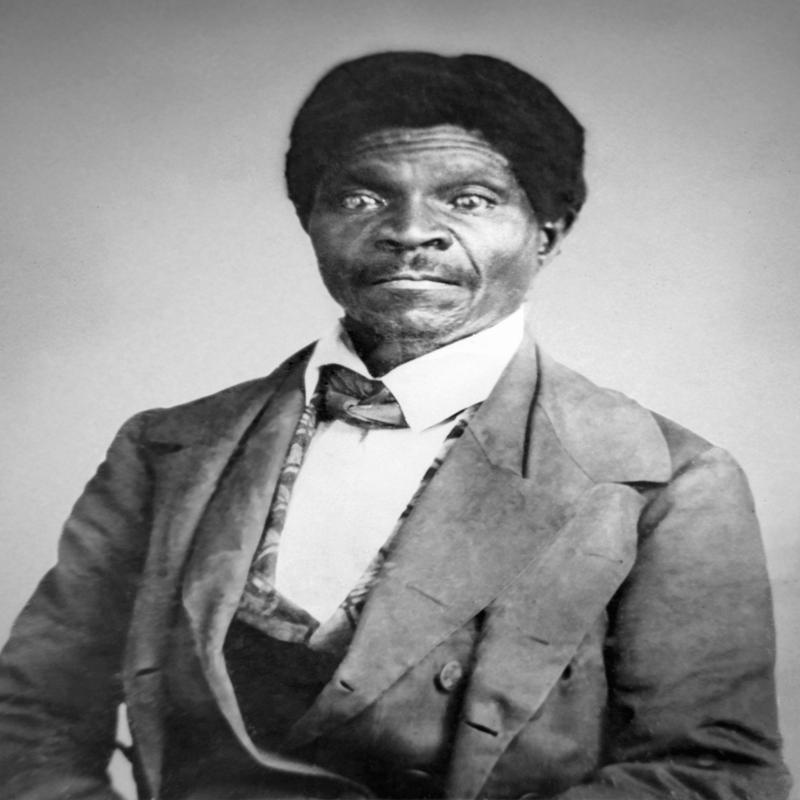

In 1857 the case of Dred Scott, a slave who taken into a non-slave holding State had with the help of the abolitionist movement sued for his freedom came before the Supreme Court of the United States which under the guidance of the Chief Justice Roger B Taney ruled that a black man had no rights that the Government need uphold.

If by ruling that black people whether slave or free could not according to the Constitution be considered citizens of the country or treated as such Taney believed that he had settled the slavery issue once and for all then he was mistaken.

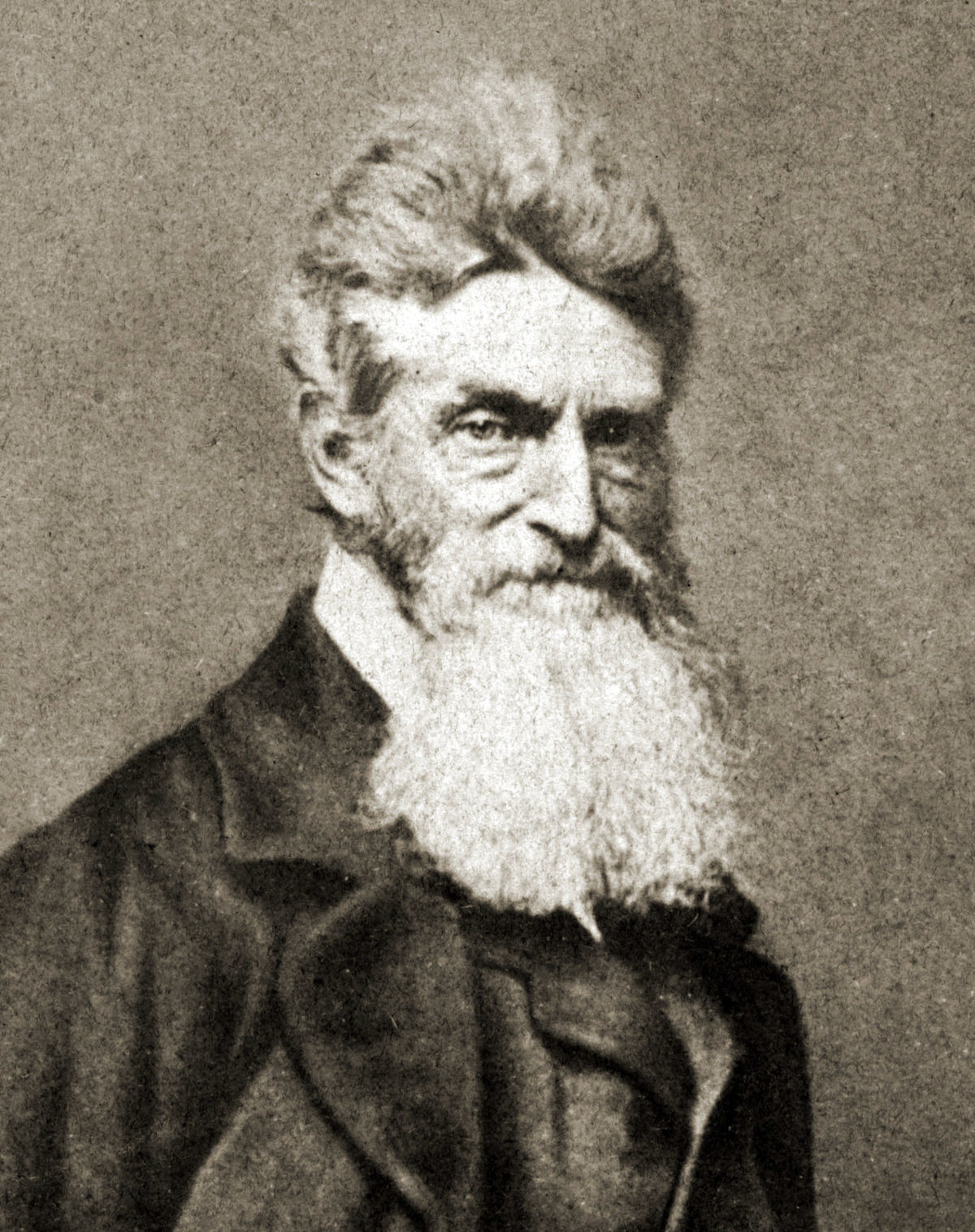

On 17 October 1859, the failed businessman and Old Testament prophet John Brown considered a murderer by some but as a hero by others led 21 men in an assault on the Federal Armoury at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, intending to incite slave insurrection.

The insurrection never materialised, and the attempt was easily, if bloodily, crushed the following day by a Company of Marines led by Colonel Robert E Lee but the thought that armed northern abolitionists were invading the territory of the south and inciting slaves to rise up and murder them in their beds sent a shiver up the spine of southerners as they now began to arm themselves, form militias and organise for a much greater conflict.

The execution of Brown for treason and inciting slave insurrection did little to placate the ire of those in the South for they knew as Brown did that it was in the deed not its outcome that his success lay. As he stood upon the scaffold he passed a note it read: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land can never be purged away but with blood.”

Many abolitionists had been quick to denounce John Brown and disavow any association with him following his attack upon Harper’s Ferry but not Harriet Tubman. She and Brown had become close in the previous years, and she had provided information, helped raise money to buy arms and acted as a recruiting agent for his attack on the Federal Armoury. Indeed, so invaluable had she become to Brown that he would call her General Tubman she in turn would remain true to his memory and for the rest of her life would refer to him as ‘her dearest friend.’

In November 1860, the Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln, an anti-slavery man but no abolitionist, won the Presidential Election with just 39.7% of the vote. He had not even appeared on the ballot paper of ten Southern States.

For many in the South the election of a ‘Black Republican’ as President was a direct threat to their very existence which despite Lincoln’s best efforts to the contrary had set the country on the inexorable path to secession and war.

Between December 1860 and February 1861 seven Southern States seceded from the Union where meeting in Montgomery, Alabama, they formed the Confederate States of America.

All attempts at a reconciliation failed and on 12 April 1861, Confederate batteries under the command of General P.G.T Beauregard fired on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor in what was an effective declaration of war.

The conflict between the States was viewed by many abolitionists as the opportunity they had been waiting for. Surely, the inevitable military defeat of the Confederacy would bring in its wake the destruction of the very institution it had sworn to defend. But they were to be frustrated by the man they had elected who refused to acknowledge slavery as an issue over which the war was being fought. For Lincoln it was about the preservation of the Union.

It was not his intention at the beginning of the war to free the slaves, but they were being freed nonetheless by Generals who took it upon themselves to treat runaways and those slaves who fell into their hands as contraband of war and northern abolitionists now travelled to those liberated areas of the South to tend to the needs of slaves rescued from the plantations. Harriet Tubman journeyed with them to Port Royal in South Carolina, the heart of secession where she intended not just to help where she could but to lead her people to freedom.

In early 1863, she moved to Beaufort where she served as a scout for Colonel James Montgomery’s 2nd South Carolina Infantry, a Regiment composed of freed slaves.

Montgomery was a controversial figure who believed it his mission to bring the Wrath of God down upon the slave owners whom he hated far more than he ever did the institution of slavery itself; and this he did in raids into the South Carolina countryside burning farms, looting towns and getting rich on the proceeds. He was not the first man of dubious repute that Harriet had formed a close association with.

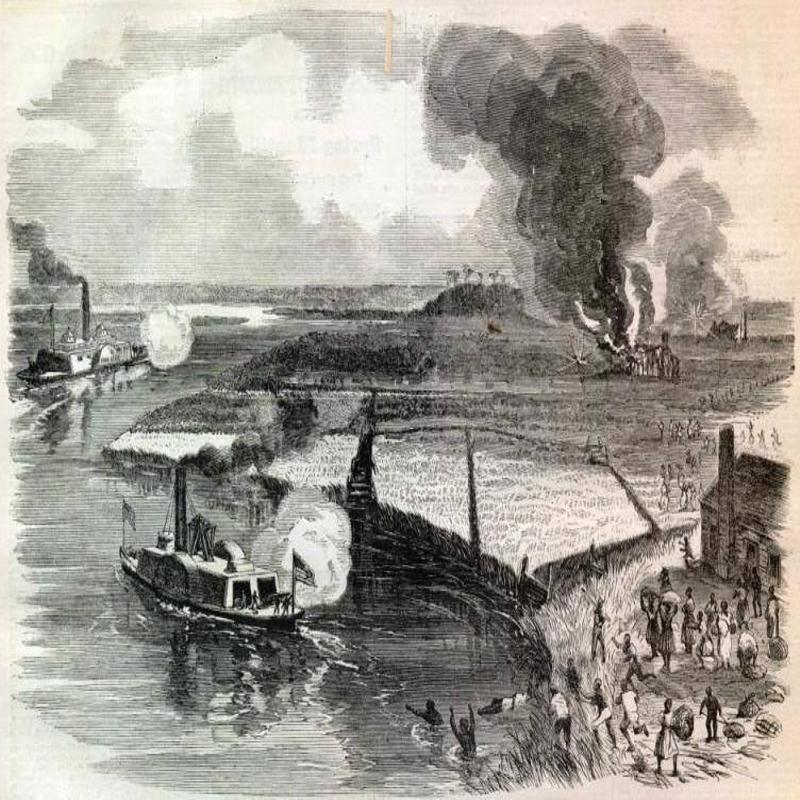

On 1 June 1863, she accompanied Montgomery in a raid on the coastal plantations along the Combahee River. During the raid various plantations were pillaged and put to the torch before Confederate troops arrived and Montgomery beat a hasty retreat. Harriet, however, was determined to take the many freed slaves back with her and so sitting upon a horse with a rifle slung over her shoulders she rode before them and like Moses leading his people to the Promised Land more than 800 or so followed her to a steamboat that took them to safety. She was ‘Mother Moses.’

Following the end of the Civil War, Harriet returned to Auburn, New York where she remained for the rest of her life. There she received the admiration and respect of those who for many years had worked alongside her but little formal recognition and certainly no pension.

Even so, she was never as poor in later life as has often been made out and she continued to work tirelessly for the rights of black people helping raise money to build schools provide for the education of black children and a nursing home for black women no longer able to take care of themselves in old age.

But her desire to see black people treated as the equals of their white brethren was to prove no less problematic than the abolition of slavery itself and she was to be deeply frustrated by the failure of Reconstruction which saw white domination re-emerge in the South under many of the same people who had been at the forefront of secession and many of them ex-slave holders.

With the land parcelled out to freed blacks in the South having been returned to its original owners many black people found themselves once again working on the plantations but this time for slave wages. Others worked the land as sharecroppers in a hard scrabble existence that barely provided them with a living.

The passage of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution which guaranteed black people citizenship, equality before the law and the right to vote appeared to mean little in the Deep South where the introduction of Black Codes and later the Jim Crow Laws effectively denied them these rights as segregation was forged under the hollow banner of separate but equal making a mockery of much that had been gained by the abolition of slavery.

Slaves no more but oppressed just the same those who refused to comply with the new reality were subject to swift retribution by white robed Klansmen.

The suppression of black rights in the South and the continued economic disadvantage of those in the North was for Harriet who remained as committed a civil rights campaigner as she had been a militant abolitionist, a cause of some bitterness.

Harriet Tubman died in the nursing home she had helped build on 10 March 1913, aged 93.

Her contribution over so many years to the abolitionist cause cannot be underestimated. Frederick Douglass, himself a runaway slave who had purchased his freedom with donations from foreign admirers and whose erudition had long made him the spokesman and public face of black freedom wrote to Harriet in a letter from 1868:

“Excepting John Brown – of sacred memory – I know of no one who has willingly encountered more perils and hardships to serve our enslaved people than you have.”

Tagged as: Miscellaneous, Women

Share this post: