Highwaymen: Stand and Deliver!

Posted on 8th February 2021

The wind was a torrent of darkness among the gusty trees.

The moon was a ghostly galleon tossed upon cloudy seas.

The road was a ribbon of moonlight over the purple moor,

And the highwayman came riding—

Riding—riding—

The highwayman came riding, up to the old inn-door. *

Eighteenth century England was a violent place and a country of extremes; of great wealth but greater poverty still with a politics shorn of scruple and a law without justice. In such a world even heroes are often more to be feared than admired - pickpockets and thieves, fraudsters and robbers on the highway – as long as they stole from the rich regardless of whether they gave to the poor they were to be honoured in the darker recesses of the human soul.

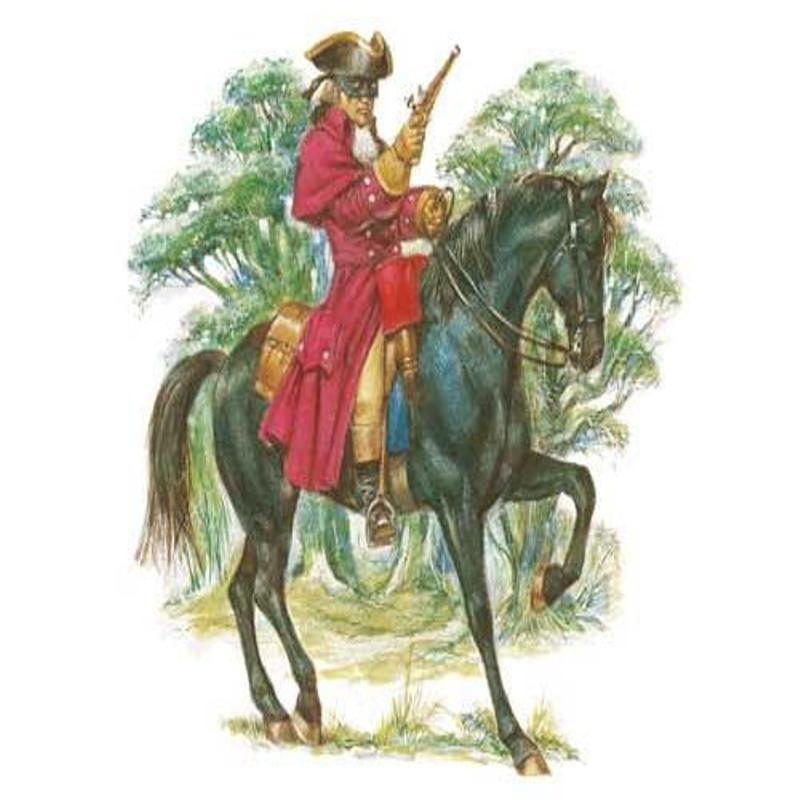

In this brutal world and with their trademark address beloved by generations of children, ‘Stand and deliver. Your money or your life’, ¬ none was more admired than the highwayman who terrorised with impunity by night those who governed with an iron fist by day.

Portrayed in popular ballad and verse as both dashing and brave, they infested the main arteries of England making travel a perilous pursuit undertaken with trepidation and for good reason. Most highwaymen made no pretence of gallantry but were violent thugs who would kill without compunction. But there were exceptions and James Hind was one. Indeed, he was to become the first criminal as folk hero since perhaps the time of Robin Hood.

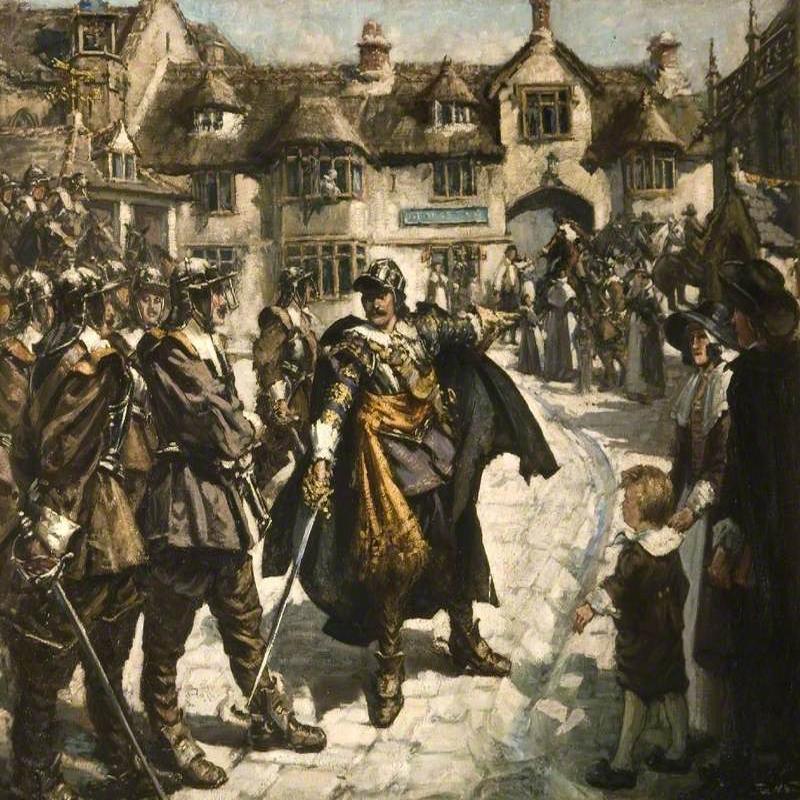

Born in the small town of Chipping Norton in Oxfordshire the humble son of a saddler, he would rise in status to become an Officer in the King’s Army during the war with Parliament where his devotion to duty was acknowledged but he could do little to alter the tide of a war that had turned decisively in Parliaments favour. Following the Royalist defeat, he briefly returned home but fearing retribution soon fled to London, a Republican city, but one upon whose teeming streets he could easily disappear and did into its many brothels and taverns, and it was in one such tavern that he met Thomas Allen, a career criminal who had already committed several robberies on the highway and was looking for a partner.

Lucrative though it was highway robbery was fraught with danger and not just for its victims. Few coach passengers travelled unarmed and the coachman himself would often carry a blunderbuss, a scattergun with a flared nozzle that fired a multitude of musket ball that could kill both a horse and its rider with a single shot. It was important then for one man to keep the passengers covered while the other would deprive them of their goods and money.

Hind, who had remained a vocal critic of the new regime, a dangerous preoccupation, was eager to be that man but unlike many others who had also shed a tear at the King’s execution his grief turned to anger, and he desired their partnership to be more than a mere criminal enterprise, he wanted it to be a continuation of the war by other means. Allen, whose sympathies likewise lay with the Cavalier cause, did not object - they would target the Regicides when the opportunity arose.

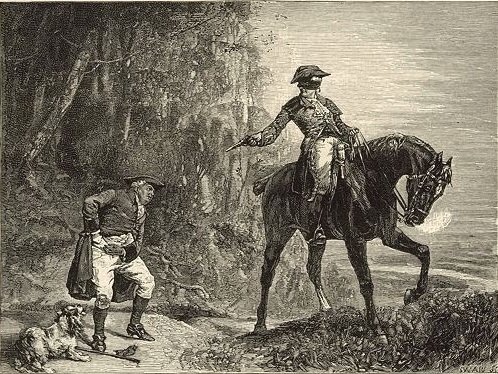

Those they stopped who could prove their loyalty to the King would be permitted to continue on their way unmolested but not so the Commonwealth Men whose lives they would threaten, their valuables they would steal, sometimes even their clothes. Many a wealthy Republican would fall foul of James Hind and Thomas Allen much to the delight of the public at large but an attack upon the arch-Regicide himself, Oliver Cromwell, would prove a step too far when they found the Lord Protector to be very well protected indeed.

Cromwell travelled nowhere without an armed escort, and it appears unlikely that Hind and Allen would have been unaware of this. They probably blundered then into the Lord Protector’s entourage rather than targeted it specifically. If so, they soon wished they hadn’t.

In the gloom of an early evening Thomas Allen’s sudden appearance and demand that they ‘stand and deliver’ seemed palpably absurd and he was quickly seized and overpowered. In the meantime, Hind fought desperately with those trying to grab the reins of his horse and pull him from the saddle. He barely escaped their clutches and with no prospect of helping his friend galloped off in the direction of London with Cromwell’s men in hot pursuit. He had been fortunate indeed, Thomas Allen less so, and he would shortly pay with his life for his audacity.

Hind may only just have eluded justice but his attack upon Cromwell made him a hero among all those who loathed the new Puritanism and there were many, or simply had a disdain for authority of which there were even more. Hind revelled in his new fame and now without Allen he could act without restraint and so it was on the road to Salisbury that he intercepted the carriage of John Bradshaw, the Chief Justice who had presided at the trial of the King. Notorious for having sat on the bench wearing a breastplate under his judicial robes and a helmet to protect against assassination he seemingly took no such precautions when on his travels. It was an astonishing arrogance on his part, and it very nearly cost him his life as with an ill-grace and a curse upon his lips he handed over all he had.

The next high-profile Commonwealth Man to fall victim to the Cavalier Thief was Hugh Peters, the firebrand preacher to Oliver Cromwell’s New Model Army who in his eagerness to see the King executed had fulminated from the pulpit: “So ye shall not pollute the land wherein ye are: for the blood it defileth the land: and the land cannot be cleansed of the blood that is shed therein, but by the blood of him that shed it.”

Having similarly admonished his current assailant with verses from the Bible it soon became Peters turn to be on the end of a sharp tongue as Hind accused him of humbug and hypocrisy, of treason and of sanctioning the murder of his divinely anointed King. If he did not comply with his demands, then a similar fate awaited him. The old preacher for all his bluster did not need to be told twice – his life would be spared but not his cane, cloak and purse.

With each robbery of a Republican, a Regicide, or a Puritan Divine, Hind’s popularity soared and his reputation along with it. It seemed there was nothing he wouldn’t do in the Royalist cause, that he was not only a confidante of the exiled heir to the throne but had helped him escape the clutches of Cromwell’s Ironsides following his defeat at the Battle of Worcester. It was even rumoured that he led a secret countrywide organisation dedicated to the Restoration of the Monarchy.

Hind revelled in the attention that came his way and would openly toast the King’s health and damn the King killing Republicans whenever the opportunity arose, but he was to engage in the drunken ribaldry of a crowded tavern once too often - overheard boasting of his exploits he was reported to the authorities and arrested.

James Hind acted in a higher cause or so he claimed, a fact not lost on the Authorities. As such he was tried not for robbery or murder but treason. An example would be made of him and speaking from the scaffold he made plain why: “The robberies I committed were upon the Republican Party of whom I have an utter abhorrence. It troubles me greatly that I shall not live to see my royal master established upon the throne from which he has been so unjustly and illegally excluded by rebellious and disloyal men who deserve to hang more than I.”

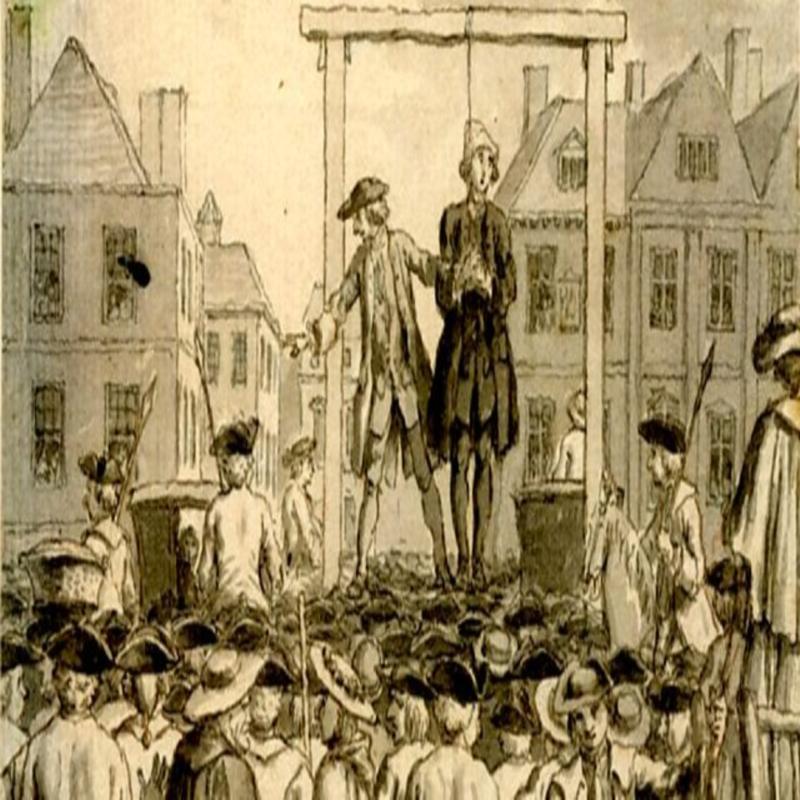

Having died a traitor’s death, hung, drawn, and quartered, his severed head was put on public display as a warning to others.

If the Cavalier Thief had stirred the blood of young men, it was an émigré French aristocrat who stole the heart of the young ladies.

The very model of the gallant highwayman Claude Duval had been born in Paris in 1643, to an impoverished noble family that had been stripped of its land and titles. With no future for him in France he moved to England where his aristocratic connections at least ensured him gainful employment; but it was never enough, and so he turned to crime to maintain a lifestyle that was otherwise beyond his means and where his courteous behaviour and dignified manner was to see the image of the highwayman romanticised as never before.

Stalking the remoter byways of North London between Islington and Highgate it was said that no one was ever harmed in a Duval robbery; that he would rather charm his victims into handing over their valuables than demand they do so, though the very notion that charm alone could induce someone to comply without the corresponding threat of a pistol to the head or a sword thrust to the chest seems unlikely.

Nonetheless charm prevailed in most cases as removing his hat he would quote verse or wax lyrical upon the vicissitudes of fortune before bowing before the lady who would curtsey in return. Then kissing her by the hand he would ask her to dance, should she agree to do so it was said he would take only half of her husband’s purse.

It was the stuff of legend and so popular did he become that many a lady of quality expressed a desire to be waylaid by the charming French aristocrat, not something likely to endear him to a jealous husband or a timorous fiancée in fear of his life. Personal enmity aside, a popular criminal dashing or otherwise could not be tolerated and the authorities were willing to pay to secure his arrest.

Sensing it was no longer safe for him in England he fled briefly to France and there he should have remained, but the lure of London’s riches proved too great. If he believed his Gallic charm and aristocratic connections would protect him, he was mistaken for not long after his return he was arrested while drinking at the Hole-in-the-Wall Tavern in Covent Garden.

Despite a public appeal for clemency Claude Duval was hanged at Tyburn on 21 January 1671, before, regardless of the great many women weeping into their silk handkerchiefs, a cheerful crowd for a cold day.

In a brief criminal career that lasted barely six months Plunkett and MacLaine made quite a name for themselves and one that far surpassed their deeds; but then it was always their intention to make an impression. That at least remained a shared ambition for two otherwise very different men.

James MacLaine was born in Ireland, the son of a Scottish Presbyterian Minister but there any nod towards sobriety ended. He was a young man on the make, flamboyant and gregarious, who openly defied his father while also burdening the old man with his many debts. Forced to marry early in the hope that the responsibility of family life might restrain him he instead moved to London where having set himself up as a grocer in name only, he proceeded to squander his wife’s inheritance on a lifestyle he believed was his by right, if not necessarily by birth.

William Plunkett was an earnest but failed businessman whose penurious situation was hardly improved on account of his association with MacLaine to whom he loaned money with little prospect of it ever being repaid. Indeed, it was MacLaine who suggested crime may be the way out of their predicament. Plunkett, who had an equally high opinion of himself agreed, but they would do so as gentlemen; and so it was wearing fancy clothes, their faces hidden by Venetian masks and with the exaggerated mannerisms they believed appropriate for men of their station they embarked upon a life of crime.

Operating for the most part in the wasteland that was then Hyde Park they committed robbery after robbery stopping carriages almost at will; so much so that one of their more high-profile victims the Gothic novelist and son of a former Prime Minister Horace Walpole would write: “One is forced to travel, even at noon, as if one is going into battle.”

The thunder and fury of war may have been an exaggeration, but no robbery was unworthy of a theatrical gesture and so while MacLaine wooed the ladies with a silver tongued charm the more morose Plunkett stripped them and their male companions of everything of value with a grimly determined but always polite menace. Indeed, so conscious were they of their public image that when it was reported shots had been fired at Walpole’s carriage MacLaine wrote a letter of apology along with a corresponding demand for money:

“Sir, seeing an advertisement in the papers of today of you being robbed by two highwaymen on Wednesday last in Hyde Park and during the time a pistol was fired intended or accidental obliges us to take this method of assuring you it was the latter and was designed by no means to frighten or hurt you for we are reduced by the misfortunes of the world to have recourse to this method of getting money. Yet we have humanity enough not to take anybody’s life where there is not a necessity. We have likewise seen the advertisement offering a reward of 20 guineas for your watch and seals which are very safe and which you shall have along with your sword and the coachman’s watch for 40 guineas and not a shilling less.”

The missive then provided for the delivery of the money before once again burnishing their image as latter day Robin Hood’s by promising to return the few pennies and cheap pocket watch they had stolen from Walpole’s poor footman.

Such apparent generosity did little to deflect from their avarice but no matter how valuable their haul MacLaine in particular, never failed to spend it. Residing in expensive lodgings with a wardrobe of fine clothes and a live-in mistress bought and paid for, he even now struggled to make ends meet and it was his pawning of some expensive lace that lead to their downfall. In attempting to sell the lace the pawnbroker inadvertently approached the tailor who had made the original waistcoat from which it had been unpicked. Aware that the waistcoat had been stolen in a robbery he reported it to the relevant authorities and MacLaine was subsequently arrested.

There is of course no honour among thieves and MacLaine immediately revealed Plunkett’s whereabouts and declared he was willing to turn King’s Evidence against him for a guarantee of immunity from prosecution. But it was the dashing MacLaine they wanted to make an example of not the dour Plunkett and it was the latter not the former who would ultimately betray his friend.

Hundreds of well-wishers visited MacLaine while he was in prison awaiting trial but his popularity was to prove no defence and he was hanged at Tyburn on 3 October, 1750. William Plunkett meanwhile, remained free to spend his ill-gotten gains and disappear into well-earned obscurity on the other side of the Atlantic.

Plunkett and MacLaine’s notoriety as highwaymen was fleeting as was that of others such as John Nevinson referred to as ‘Swift Nicks’ by no less than the King himself and ‘Sixteen String’ Jack Rann so named because of the colourful silk stripes he had elaborately sewn into his breeches. None however acquired a fame as enduring as Dick Turpin’s, his was a legend that grew largely after his death the result of William Ainsworth Harrison’s popular 1830 novel Rookwood in which he appeared as a peripheral but particularly vivid character.

Richard 'Dick' Turpin was born in the Bluebell Inn, Hempstead, Essex, in September 1705, the son of a butcher in whose trade he followed and it was in fencing stolen livestock and poached meat that he became part of the local crime scene. It was after all easier money that the long hours and hard graft of butchery and by 1734 he was operating as a member of the Essex Gang led by the brothers Samuel and Jeremiah Gregory. So it was not as a highwayman that Dick Turpin cut his teeth as a career criminal but in street robbery and burglary, and as part of a large organised gang.

In February 1735, Turpin along with four other members of the Essex Gang broke into the isolated farmhouse of 70 year old Joseph Lawrence who, while his two maidservants were bound and gagged and made to look on was severely beaten and forced to strip. Even so, he stubbornly refused to reveal where he had hidden his money. A furious Turpin pistol-whipped the old man before the other members of the gang took him and began roasting his bare buttocks over the open fire. They even poured a kettle of boiling water over his head but even in great pain and in fear of his life he would not give up his fortune. In their fury the Gang ransacked the house while the Gregory brothers took the maidservants to an upstairs room and raped them.

Later that same month the Gang broke into another isolated house, this time belonging to an elderly widow Elizabeth Shelley who they again brutalised before escaping with £100 and her silver plate.

This is not the popular image of Dick Turpin the highwayman we have today but the Lawrence and Shelley robberies were just two of a series of violent incidents that occurred in fairly quick succession. Indeed, the fear they spread forced the Authorities to act and using paid informers and Government spies the Gang was infiltrated, broken up, its members arrested, and in the case of the Gregory brothers hanged. Only Dick Turpin of the dozen or so gang members escaped justice but he was now a marked man.

The Duke of Newcastle offered a substantial reward for his arrest while his description was widely circulated to the press. This one appeared in the London Gazette:

“A butcher by trade about 26 years of age, a tall fresh coloured man very much marked with the smallpox. Lived some time ago in Whitechapel and wears a blue grey coat and natural wig.”

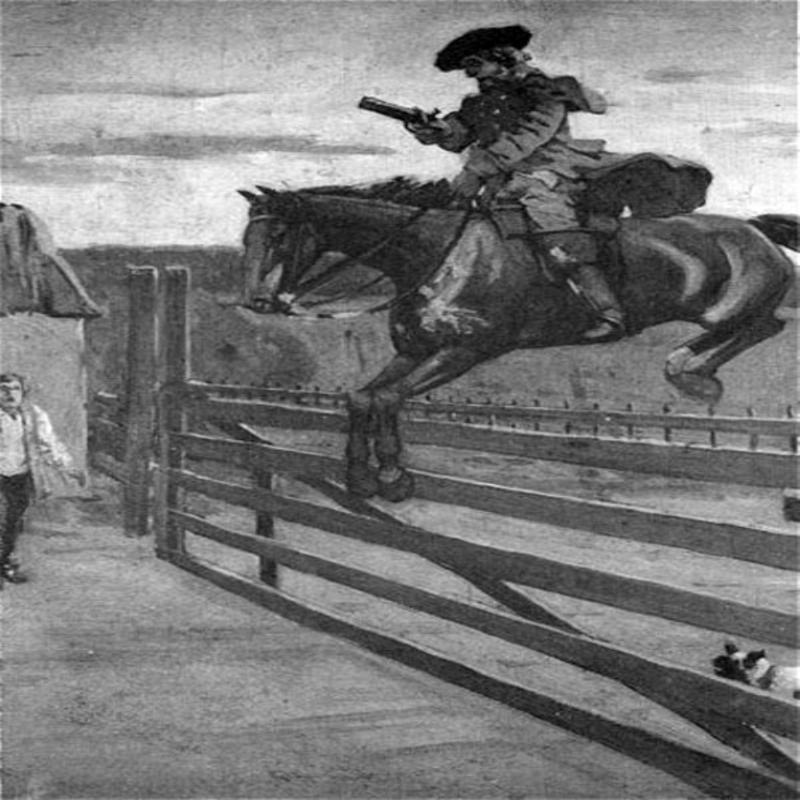

Turpin had indeed fled to the anonymity of the smog-bound city, but he did not lie low for long before turning once more to crime, this time highway robbery but it wasn’t for the most part well-armed carriages he targeted but lone travellers vulnerable and defenceless amid the woodland and bleak moors that still surrounded much of London. He also rarely worked alone his most regular accomplice being Matthew King with whom he carried out a great many robberies, but a partner in crime is not necessarily a friend as he was soon to discover. Cornered while attempting to steal some horses King was overpowered and called upon Turpin who had initially fled the scene to return and save him. Turpin did return and drawing his pistol shot King dead. It may have been unintentional the result of a confused melee, but with his partner’s death Turpin’s whereabouts for now remained secret. Even so, he took the precaution of moving to Epping Forest an area he knew well but with a £200 reward on his head familiarity alone provided little cover and on 4 May 1737 he killed Thomas Morris, a servant to one of the Keepers of the Forest, who having recognised the notorious highwayman had attempted to apprehend him.

The cold-blooded murder of Thomas Morris, a respected servant who had been shot without warning in a cowardly attack was widely reported the length and breadth of the country making Turpin for a time at least the most wanted man in England. One such report appeared in the Gentleman’s Quarterly of June 1737:

“It having been represented to the King, that Richard Turpin did on Wednesday the 4th of May last, barbarously murder Thomas Morris, Servant to Henry Tomson, one of the Keepers of Epping Forest and commit other notorious felonies and robberies near London, his Majesty is pleased to promise his most gracious pardon to any of his accomplices, and a reward of £200 to any person or persons that shall discover him, so that he may be apprehended and convicted. He is by trade and butcher, about 5 feet and 9 inches high with a brown complexion very much marked by the smallpox, his cheek bones broad, his face thinner towards the bottom, his visage short, upright, and broad about the shoulders.”

Turpin was forced to flee once more this time in haste, and it was now that according to legend he rode his trusty mare Black Bess through the night on an epic 11 hour 200 mile race to York pausing only briefly to cool her down with a mixture of water and brandy. It did prove enough to save her life, and no sooner had they reached their destination than her heart burst and with blood pouring from her nostrils she dropped dead of exhaustion.

It was a great story, and it almost certainly wasn’t true. A similar journey had been undertaken by John Nevinson many years before when he sought an alibi for a vicious robbery committed in London by being seen to play a game of bowls with the Mayor of York not long after, but it was at least true that Turpin had fled to the city where he lived under the alias of John Palmer.

Throughout Yorkshire and neighbouring Lincolnshire Turpin embarked upon a crime spree teaming up with others to commit robberies but also to engage in poaching and particularly lucrative horse theft, but he had also taken to drinking heavily and his behaviour had become increasingly erratic as a result. It would land him in a heap of trouble.

On 2 October 1738, having returned from a hunting trip with friends the worse for wear and in a foul mood he shot dead another man’s expensive cockerel in what appears to have been an act of malice. Reported to the local Magistrates, John Palmer as he was known was arrested. Although he was able to pay the fine that was imposed upon him, he instead refused to do so pleading his innocence. Detained in prison an investigation was now undertaken into the true identity of this man who lived the high life in York’s taverns and brothels while seemingly having no gainful employment. He was certainly not the simple butcher he claimed to be and was suspected of being a horse thief, poacher, and rustler of sheep and cattle but not yet the notorious Dick Turpin.

Following his arrest Turpin was also accused of stealing a horse which had been a capital offence since 1545 and though it was by now rare for such a harsh penalty to be imposed it might have been wise at this point to plead guilty and pay the subsequent penalty but still he stubbornly refused to do so - his case would come to trial.

With no Defence Counsel provided for the accused he would be expected to represent himself and Turpin was to prove a particularly poor advocate in his own defence. Indeed, it was his ham-fisted attempt to find character witnesses willing to testify on his behalf that was to prove his undoing.

One of those he approached was his brother-in-law who not wanting to get involved refused even to open the letter he had received but neither did he choose to destroy or conceal it. James Smith who had taught the young Richard Turpin how to write and was still in contact with the family saw the envelope and recognising his distinctive style wrote to the Court in York to inform them that it was not John Palmer they had under arrest but the notorious highwayman Dick Turpin.

The Judge presiding at the trial Sir William Chapple was determined that Turpin should hang and now charged with horse theft he had the crime by which to do so. There was no need to seek further proof of his identity or charge him with further felonious acts the capital crime had already been committed. In its haste to conclude the trial became a farce with incorrect dates, doubtful eyewitness accounts, and tainted evidence. Any competent Defence Counsel would have seen the case thrown out of court, but Turpin had none - he was sentenced to hang.

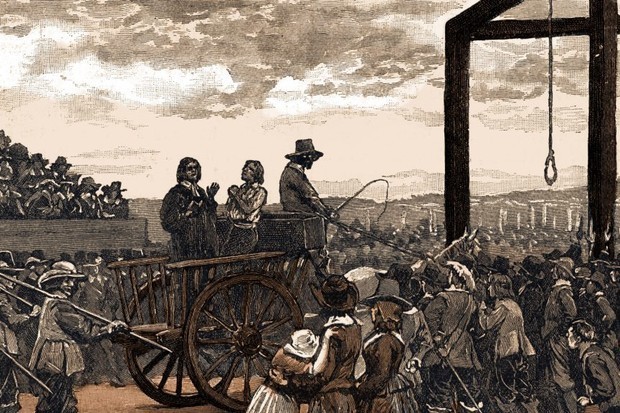

The most notorious criminal in England hundreds of people visited Dick Turpin while he was in jail and thousands would attend his execution to see how he died – he would not disappoint. He bought a new frock coat and shoes for the occasion, paid for mourners to accompany his cart as it took him through the streets of York to his place of execution. He even joined in the carnival atmosphere: “Turpin behaved himself with amazing assurance and bowed to spectators as he passed.”

But for all the bravado Dick Turpin was no less fearful of imminent death than anybody else and as he ascended the ladder to the scaffold his right leg trembled, so much so that he had to pause and stamp his foot to bring it under control and regain his composure. Perhaps he could sense his nerve was failing him or maybe it was to avoid the short drop that ensured slow strangulation that compelled him to jump with force before reaching his destination. If he thought his leap into eternity would snap his neck, then he was mistaken and he would dangle from the rope struggling for breath for a full five minutes before he finally died.

Dick Turpin’s notoriety like others before was fleeting but would be revived in William Ainsworth Harrison’s novel and become legend. Yet the day of the highwayman had already passed. Indeed, it was only a year after the novel’s publication that the last such recorded incident occurred. It had been then, a crime of a very specific period and there was already a nostalgia for it long before one era had evolved into another. For those who were never its victim and were in little danger of ever becoming so the highwayman was a folk hero, a man to be admired by the many who would never dare trespass the law of their own volition. It was not the first time the criminal has been elevated to a status unbecoming his profession, there is perhaps just something in the human condition restrained by a common decency that seeks validation in the activities of those who have no such qualms, as long as they do so in a manner otherwise acceptable to polite society. So those like John Hind who had the noble cause, Claude Duval the charm, and Plunkett and MacLaine the daring, would be idolised. Yet it would fall to Dick Turpin, a man who could lay claim to none of the above who would live on in time and space and come to epitomise the highwayman as something other than a common criminal in the historical narrative.

Tagged as: Georgian

Share this post: