Hirohito: The Emperor's New Clothes

Posted on 28th March 2021

The Second World War had ended with Adolf Hitler dead by his own hand and Benito Mussolini shot and strung up by his ankles from a Milan petrol station. In the chaotic months that followed those held responsible for genocide were hunted down and put on trial for their crimes. Yet in Tokyo the Emperor Hirohito, the absolute ruler of Japan and a living God to whom every Japanese owed their lives was never charged with any misdemeanour and was to reign for a further 44 years.

For much of its history the Japanese Emperor had been little more than a figurehead who was forced to yield to the power of the warlords, in particular the Shogun who would be chosen to govern the administration of the Empire. He was drawn from the most powerful family and effectively ran a feudal dictatorship. They in turn, would often be in conflict with the Samurai who would in time become the prevailing military force in Japan.

Japan’s traditional isolation was challenged however, by the arrival on 8 July 1852 of Commodore Matthew C Perry with a powerful fleet and orders from the President of the United States Millard Fillmore to open up Japan to American trade, by force if necessary.

Sailing off the coast of Uraga with his ship’s guns pointing towards the town he refused orders to leave and instead demanded that the Japanese accept a letter outlining American proposals. Once they had done so he departed but curtly informed them that he would return to receive their reply. In February 1854, he did so and with a naval squadron twice the size and like nothing the Japanese had ever before seen; and he was unequivocal in his demands, the matter was not open to negotiation, the Japanese would either open a series of ports to American trade or he would open fire and take them by force.

Given Commodore Perry’s uncompromising attitude the Togugawa Shogunate had little choice but to yield and they proceeded to sign a number of agreements that were so favourable to the Americans they became known as the Unequal Treaties. It was a humiliation they would not easily forget but also one from which they would also learn.

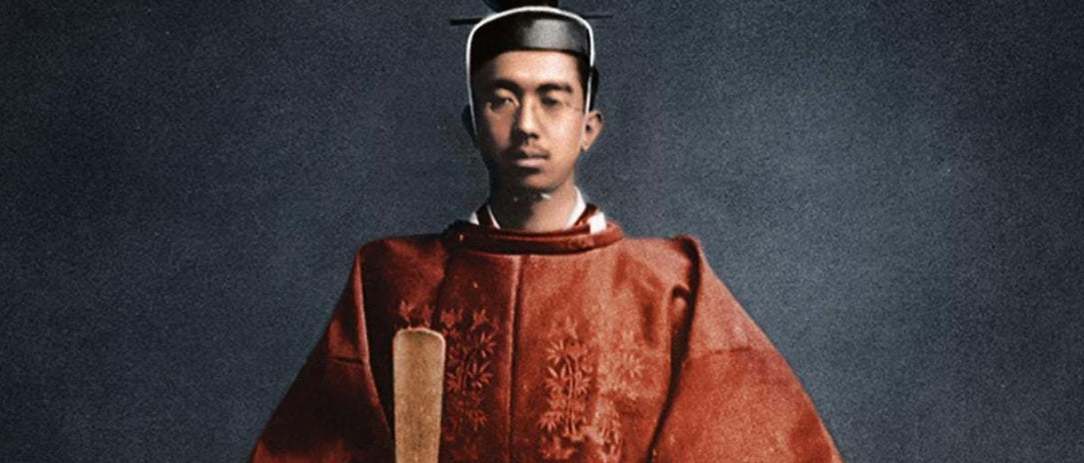

On 3 February 1867, the Meiji Emperor Mutsuhito ascended to the Chrysanthemum Throne and though there had already been some progress towards modernisation he was determined to speed it up and make Japan a regional and world power. He was supported in his ambition by many of Japan’s intellectuals, merchants and bureaucrats.

A conscript Imperial Army trained and armed by the Americans and commanded by turncoat Samurai Officers now posed a direct challenge to the role of Imperial defence that had long since been the role of the Samurai. The struggle between modernisers and traditionalists reached its zenith on 4 January 1868, when the Meiji Emperor announced that the Shogun Yoshinobu had been removed and that in the future power would reside with the Imperial Throne. It was a decision that would be resisted.

The Satsuma Revolt as it became known pitted 300,000 Imperial troops armed with modern weapons against 20,000 Samurai in what was from the first an unequal struggle. Even so, the revolt did not end until September 1877 and the defeat and death of Saigo Takamuri in what is now considered the last stand of the Samurai warrior elite.

The military victory of the modernisers, the abolition of the Shogunate, the restoration of Imperial rule and the passage of the Meiji Constitution of 29 November 1890 set Japan on the path to becoming a global power.

The Meiji Constitution had followed many Western precepts including that of religious toleration but over the next few years Shinto came to dominate and other religions such as Buddhism and Christianity were suppressed and their adherents subject to abuse and intimidation.

State Shintoism declared the Emperor of Japan to be descended from an unbroken line that went back 2,500 years to the dawn of time and the first Emperor Ameterasu. As such the Imperial Family were older than the Japanese people themselves.

This had previously been just one among many myths but now with the introduction of State Shintoism it became fact and the Emperor acquired Divine status as the direct descendant of God. The future Emperor Hirohito’s status as a living God gave him not only the unchallenged right to rule Japan and its people but made them in their turn superior to any other race.

The future Emperor Hirohito was born on 29 April 1901, in the Aoyama Palace in Tokyo. As heir to the Chrysanthemum Throne, he was raised in splendid isolation and rarely left the confines of the Imperial Compound. He was by all accounts a shy and nervous child who lacked confidence and was accident prone with even his own brother saying that when he fell over, he was so fumbling that he was unable to get up again unaided.

He succeeded to the throne on 25 December 1926, following the death of his father Taisho who had been ill for some time. His reign would be known as the Showa.

The modernisation of Japan had seen the country end its traditional isolation and be transformed from a regional backwater to an economic, industrial and military world power in just 40 years. The change was too rapid for many and throughout that period there remained a strong yearning to return to a more traditional Japanese way of life.

In October 1929, the Wall Street Crash plunged the world into an economic depression and no country was hit harder than a Japan which had yet to fully recover from the devastating effects of the Yokohama and Tokyo earthquakes. Some viewed these catastrophes as a punishment from the Gods for abandoning Japanese traditions while others saw it as proof that the experiment in Western politics and values had failed.

The number of societies dedicated to the spiritual purification of Japan and practising the Samurai code of Bushido multiplied and spread rapidly especially among the military. Declaring their devotion to the Emperor and advocating militarism and national chauvinism they began to dominate the political agenda and those who opposed this backward trend and continued to believe in democratic values and good relations with the West became increasingly subject to scorn, intimidation and even murder.

Japan struggled more than most to emerge out of the economic depression because it lacked raw materials, it had no oil, no coal and no iron ore among many other things and its agricultural yield was barely enough to feed its own population which was increasing at over a million a year.

Japan needed to expand and take these things for themselves and their victories in the Sino-Japanese, Russo-Japanese, and Great War had given them a growing sense of military invincibility.

The Government was desperate to rein in the power of a military that seemed determined to provoke a war but it received little support from an Emperor who felt comfortable in the company of Army Officers, accepted their pledges of devotion to his person without question and was happier reviewing the troops than he was in debating political issues with his Ministers.

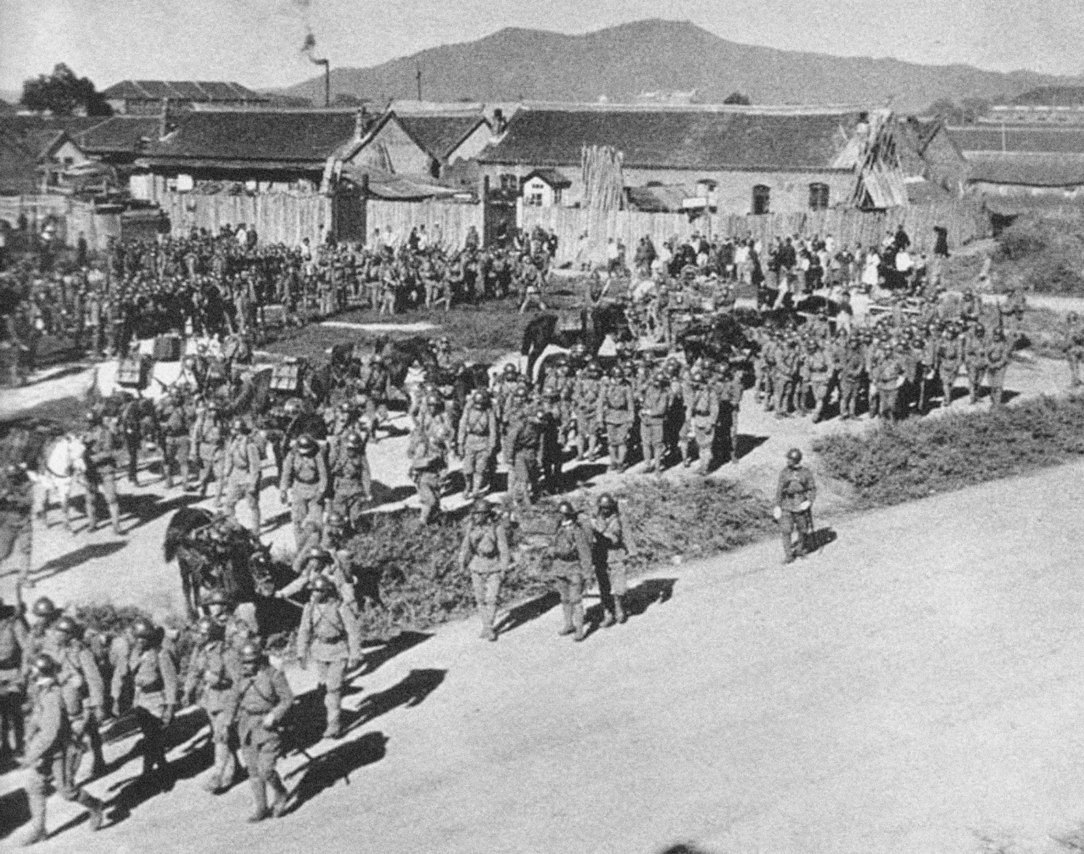

When on 18 September 1931, the Japanese Kwantung Army following an incident at Mukden invaded Manchuria despite having received express orders from the Government not to do so Hirohito stood aside and said nothing. Again, on 15 May 1932, when the Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi was assassinated for signing the London Naval Treaty that limited the size of the Japanese Navy, Hirohito remained silent and the perpetrators went unpunished.

Hirohito’s refusal to become involved and support his government in their struggles with the military, particularly the army, convinced some that they could act with impunity in the Emperor’s name and with his consent.

On 26 February 1936, Officers of the 1st Guards Division in Tokyo sought to assassinate those politicians they thought disloyal to the person of the Emperor and traitors to Japan. Among them were the former Prime Minister Makoto Saito and the Inspector-General of the Armed Forces Watanabe Jotaro both shot, while the 82-year-old Finance Minister Korekiyo Takahashi was hacked to death in his bed. Many others barely escaped with their lives.

Informed of the coup, Hirohito who had done nothing to oppose the military in the past appalled at the bloodshed and the threat posed to his Throne for the first time in his life displayed a resolution that had previously been thought lacking. He rejected the notion that they were acting on his behalf and ordered the coup be crushed.

Some Senior Officers tried to persuade the Emperor to mollify his response and seek a negotiated settlement but he remained adamant and reluctantly they ordered troops to surround the rebels. Outnumbered the rebel Officers sent a message to Hirohito declaring that they would be willing to surrender if their Emperor ordered them to do so but sought permission to commit ritual suicide according to the code of Bushido. Hirohito refused the request and the rebellion had to be ended by force and those rebel leaders who were captured were subsequently tried and executed.

To those in the Civil Administration and indeed to many people at large this seemed to be the moment the Emperor at last asserted his power and his right to rule. He had taken on the army and won, and they hoped it was a sign of things to come, but it wasn’t. Hirohito wished only to never to find himself in such a position again. He wished to reign not rule, and instead of clamping down on the military in the wake of the failed coup he acquiesced to their demands once more. He would instead hide behind the cloak of custom, of ritual, of arcane protocol and in the mystery of his Divine status. With the Emperor unwilling to intervene the responsibility for opposing the grip of the military fell to a series of Prime Ministers who were too weak and afraid to do so.

Hirohito always trusted the military more than he did politicians for whereas the former pledged loyalty and provided him with victories the latter were devious and only presented him with problems. And so it would remain in the months leading up to Japan’s intervention in World War Two.

At the meeting held to discuss Admiral Yamamoto’s plans to assault the American Pacific Fleet stationed at Pearl Harbor, the Emperor who rarely spoke in Cabinet merely nodded his assent; and to those who have long argued that he had wanted peace all along his behaviour at pivotal times on the road to war when he neither questioned nor acted to impede the aggressive stance being adopted would seem to indicate otherwise – as the absolute ruler of Japan no war could have been declared without his approval.

The day following the successful attack upon Pearl Harbor the Emperor was said to be in excellent mood it improved even further over the next few months as Japanese forces swept all before them. The Generals had promised him a swift victory and now they appeared to be delivering it. But the swift victory remained elusive.

A little more than six months after the stunning success at Pearl Harbor defeat at the Battle of Midway turned a war of conquest into a struggle for survival.

The attack upon Pearl Harbor was carried out as the precursor to a land grab and the seizing of essential raw materials in the Pacific and South-East Asia but it had also been intended to shock the United States into suing for peace; that the destruction of the American Pacific Fleet and the conquests that followed had failed to do so ensured a drawn out conflict which could only end in defeat for Japan; the High Command knew this, the Political Establishment knew this, and so did the Emperor Hirohito.

Despite the inevitability of defeat the Japanese High Command would not countenance surrender and neither would the Emperor and though his public appearances remained rare he was often to be seen on newsreel in full military regalia reviewing the troops. He frequently issued messages encouraging those in the Armed Forces to ever greater effort and sacrifice. Everything done was done in the name of the Emperor. Newsreels showed him visiting the Yasukuni Shrine dedicated to the memory of those who had sacrificed their lives for their Emperor where he would personally pray for the repose of their souls – despite always maintaining his distance Hirohito was an active participant in the war effort.

By May 1945, with the war against Germany already won the continuing conflict against Japan seemed like a sideshow and there was little desire on the part of the Allies to participate in an invasion of the mainland. The sacrifices made on Iwo Jima and Okinawa had convinced them that the Japanese would defend their homeland with a fanaticism that would prove very costly in Allied lives.

The carpet-bombing of Japan’s cities had been underway since the night of 9 March 1945, when 334 American B29 Super-fortresses attacked Tokyo. The wooden houses that made up most of the densely populated city burst into flames and it is believed that as many as 100,000 people were burned alive or suffocated to death.

Similar raids soon followed on Kobe, Osaka, and Nagoya with similar casualties, but it did not induce Japan to surrender and combat operations on the mainland appeared unavoidable - but there might be another way.

As long ago as 9 October 1941, before America found itself at war President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had approved a programme for the development of an atomic bomb. Under the guidance of Professor Robert Oppenheimer, a team of top nuclear physicists were formed to work on what was known as the Manhattan Project at the remote location of Los Alamos in the New Mexico Desert. On 16 July 1945, at Alamogordo the first nuclear bomb was detonated.

Instructed to do so by the Emperor the Japanese Government tentatively approached the Allies seeking peace. They wanted an assurance that the Chrysanthemum Throne and the Emperor’s sovereignty would remain inviolate. The response was no negotiations only unconditional surrender as had been outlined in the Potsdam Declaration of 26 July 1945. It also stated ominously that Japan could expect “prompt and utter destruction” if it did not surrender, though no mention was made of the atomic bomb.

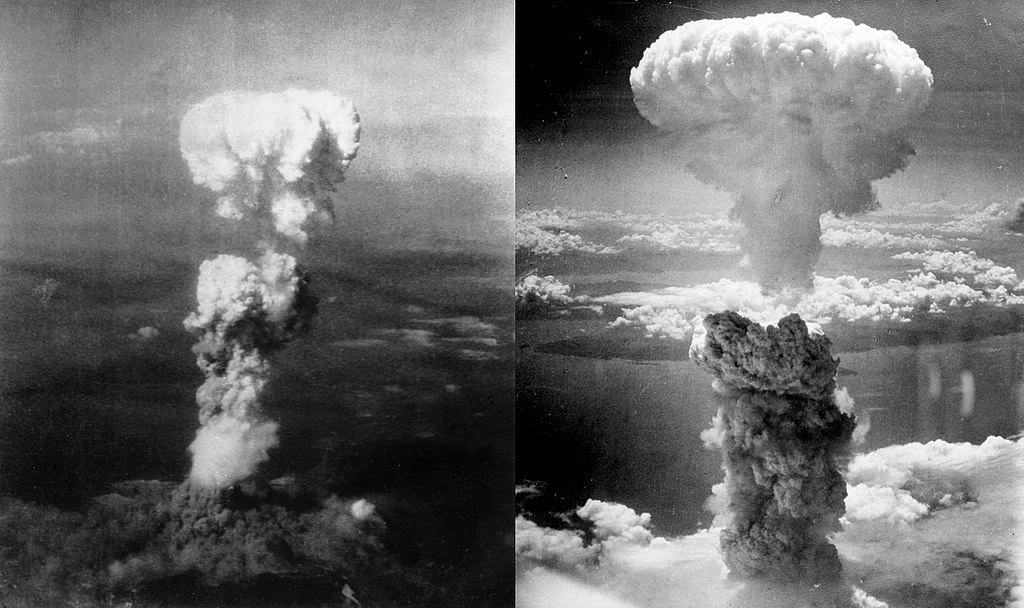

At 8.15 am on 6 August, a beautiful sunny morning without a cloud in the sky, the B29 Bomber Enola Gay, dropped the world’s first atomic bomb on Hiroshima, just 43 seconds later the city was obliterated and 80,000 people with it.

The reaction in Japan was not the one of shock expected, Japanese cities had already been razed to the ground after all and so when the American’s issued a warning that if Japan did not surrender the bombs would continue to fall – the response was silence.

On 8 August, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and invaded Manchuria where for the first time in the war Japanese soldiers began to lay down their arms and surrender in large numbers. The destruction of the Kwantung Army was now only a matter of time.

On 9 August, a second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki and again it resulted in utter devastation killing more than 60,000 people.

The dropping of the atomic bombs to which the Japanese had no answer at last convinced the Prime Minister Kantaro Suzuki and others within the Imperial Council to agree to the humiliation of surrender. Hirohito would not oppose then and on 10 August the decision that Japan would be willing to surrender, subordinate itself to American rule, and subject itself to an army of occupation was relayed to the Allies.

It had proved impossible to keep secret the Emperor’s intention to issue a declaration of surrender. There were many especially among the military unwilling to accept the reality of defeat and would rather see the destruction of Japan than yield to such dishonour.

Fear of the army’s reaction should the news of surrender leak out provoked the Minister for War Korechika Anami to assemble those senior Officers present in Tokyo to put their signature to a statement that read, “The Army will act in accordance with the Imperial decision.” It did so.

The real threat was posed not by the Senior Command of the Japanese Army however but by its Junior Officer Corps.

Earlier Anami had been approached by several Junior Officers led by Major Kenji Hatanaka seeking reassurance that the Imperial Council had no intention of accepting the terms of the Potsdam Declaration. Anami had been ambivalent and evasive in his responses. Hatanaka knew what this meant. Convinced that the Emperor would never willingly submit to surrender and that he must have been coerced by his corrupt and cowardly Ministers he prepared to act.

At 9.30 on the night of 14 August, in what became known as the Kyujo Incident, Officers of the Japanese Imperial Guard attempted a coup d’etat. They intended to seize the tape of the surrender declaration before it could be broadcast, at the same time Hatanaka despatched hit squads under the command of Takeo Sasaki to assassinate the Premier and those other Ministers he considered dishonourable traitors and no longer worthy of life.

An attempted coup was not unexpected however, and most forewarned had already gone into hiding.

The Imperial Palace was well defended but Hatanaka rather than try to force his way in persuaded the Commander of the Guard to allow him and a few of his men entry. They now hurriedly hunted high and low for the recording of the broadcast but as a precaution it had already been spirited away.

Hirohito, aware of events had hesitated to act until finally at 3.00 am he ordered troops to surround the Imperial Palace. Around the same time Hatanaka unable to persuade General Takeshi Mori, Commander of the Imperial Guards Division, to sign an order placing the Emperor under house arrest shot him dead.

Colonel Haga of the Imperial Guard, who had done nothing to protect his Commanding Officer, now informed Hatanaka that troops of the Eastern District Army were marching on the Palace and ordered him to leave but Hatanaka unable to find the recording begged to be permitted to broadcast on N.H.K, the Japanese State Radio to explain his actions – the request was denied.

In a last desperate attempt to prevent the surrender from being accepted Hatanaka drove around the streets of Tokyo tossing out leaflets from a car window and shouting warnings to people of the treason that was about to take place. But there was little response. In despair, an hour before the broadcast was due to be made, he put a pistol to his head and shot himself.

At noon on 15 August, the Emperor Hirohito broadcast to his people. It was for most the first time they had ever heard their Emperor’s voice and he spoke in a little used courtly Japanese that it was difficult for many of them to understand. He also avoided using the word surrender, but they were able to make out the phrase “endure the unendurable and bear the unbearable.” It was clear, Japan had lost the war.

Hirohito fully expected to be put on trial for war crimes and unlike so many who had borne the responsibility for Japan’s defeat he never contemplated suicide, neither did he consider abdicating the throne. Instead, he awaited the arrival of the Americans and prepared his defence.

Despite being Absolute Ruler of Japan, Commander-in-Chief of its Armed Forces and a Living God he was to claim that he was effectively powerless, a prisoner of the military, locked up in the splendid isolation of the Imperial Palace, ill-informed and with little influence.

The Japanese hurriedly destroyed all documentation relating to the Emperor’s role in the war.

On 30 August, General Douglas MacArthur, Commander of the United States Army in the Far East, arrived in Tokyo to take charge. There was no rush on the part of the Allies to seize Hirohito or place him under arrest. On 27 September, he summoned the Emperor to a meeting at the U.S Embassy. Never shy of publicity MacArthur had ensured that cameramen were there to capture the moment. The photograph taken was published around the world. It showed the tall American in military uniform towering above the diminutive Emperor dressed somewhat comically in morning dress. There could be little doubt who now ruled Japan.

MacArthur, always supremely confident, some might say arrogant, and with political ambitions of his own set about his task of transforming Japan with gusto. When he charged Japanese civil servants with the task of writing a new constitution and they returned with something that only reflected variations of the old Japan and the Meiji Constitution he had Army officials come up with one for them. He was equally decisive in other areas and the building blocks he put in place were to lead to one of the most startling political and economic revivals in history but for the time being the problem of what to do with the Emperor remained.

MacArthur and many in the American Administration did not want Hirohito put on trial. There were many reasons for this: the requirement for Japan to become a bulwark against the spread of Soviet influence in South-East Asia was considered essential and the threat of communism taking hold in war-ravaged Japan was greatly feared. Also, many Japanese still owed an oath of personal loyalty to the Emperor and any transition to democracy would be much easier with the Emperor as Head of State even if he was only a figurehead. The clamour for the Allies to put the Emperor on trial for war crimes was deafening however, it would be difficult to deflect and it was thought at the very least that he would be forced to abdicate.

Under pressure from the Americans on 1 January 1946, Hirohito publicly renounced his divinity but for him to remain Constitutional Monarch he would have to be exculpated from all blame and someone else would have to take responsibility for the war and all its subsequent atrocities.

The man chosen was Hirohito’s favourite soldier, Hideki Tojo, who had been Prime Minister between 17 October 1941 and 22 July 1944, and had only reluctantly been dismissed by the Emperor. He had been an enthusiastic advocate for war and of its continuation at all costs. Utterly devoted to the person of the Emperor he had already expressed his wish to shield him from any blame and would say anything that was required to do so.

Tojo as scapegoat had almost been lost to the Americans when on 8 September, he had tried to commit suicide by shooting himself through the chest. He failed but only just.

At his subsequent trial for war crimes in the autumn of 1948 he took all responsibility for the war and of any atrocities that had been committed by the Armed Forces of Japan throughout its duration. Sentenced to death he was hanged on 12 November 1948, maintaining throughout that as far as Japan was concerned the war had been a righteous and just one.

Hideki Tojo’s execution cleared the way for the Emperor Hirohito’s rehabilitation. But he was far from blameless:

The war had been fought in his name, he had been regularly updated on how the conflict was proceeding both in Cabinet and through informal meetings, and though he neither ordered nor personally condoned the brutalities that occurred he would have been made aware of them. The ill-treatment of Allied prisoners had been Japanese policy and not merely the result of sadistic Camp Commanders and savage guards, likewise the inhuman behaviour of Japanese Forces towards civilian populations in China and elsewhere.

Similarly, he had been made aware of the activities of Unit 731 known euphemistically as the Epidemic Prevention and Water Purification Department but in fact responsible for human experimentation and the development and utilisation of in chemical weapons which were used extensively in China. Indeed, its facility in Manchuria was visited by the Emperor’s brother Prince Mikasa and film footage of the Unit’s activities was shown at the Imperial Palace, though it is not known if the Emperor attended the screening. The Unit’s scientific coordinator Shuru Ishii also regularly lectured in Tokyo.

Hirohito also condoned the use of Kamikaze suicide pilots during the war and did nothing to deter Japanese civilians taking their own lives and that of their children rather than endure the shame of living under foreign occupation. Indeed, they were encouraged by the army to do so.

In November 1946, Emperor Hirohito formally accepted the new American drafted Constitution for Japan that enshrined him as the symbolic Head of State.

The role of Constitutional Monarch did not come easily to Hirohito as no longer the elusive, untouchable God he toured the bomb ravaged cities of Japan. The common people could see their Emperor up close for the first time, they could speak to him they could even shake his hand, but he was awkward in his manner, hesitant in his speech and evidently ill at ease. He was no man of the people and as soon as he could he retired to the confines of the Imperial Palace where he indulged his love of the natural sciences writing a number of books on the subject of marine biology. But he would over time grow accustomed to his role as a Constitutional Monarch.

As the decades passed and the collective memory dimmed a new generation wishing to put the horrors of the World War behind them began to see the elderly Hirohito as essentially benign. In 1971, he was granted a State Visit by Queen Elizabeth II where he rode in the Royal Carriage through the streets of London and stayed at Buckingham Palace.

Four years later invited to the White House by President Gerald Ford where he visited Disneyland and had his picture taken with Mickey Mouse – from Supreme Warlord to genial grandfather his rehabilitation was complete.

Tagged as: Modern

Share this post: