Hypatia: A Woman of Substance

Posted on 27th February 2021

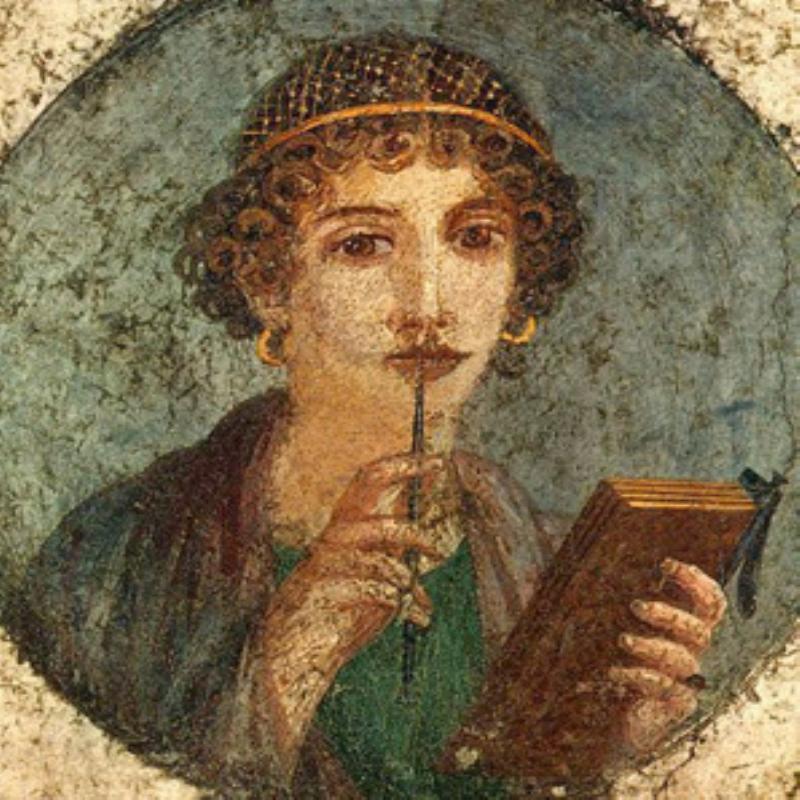

Hypatia was a philosopher, mathematician, inventor and no doubt many other things besides; some would say she was a woman of genius and a question mark might follow but she was a woman of substance and of influence and she would pay for being so with her life.

Of Greek descent she was born in Alexandria around AD 370 during the dying embers of the Roman Empire, the daughter of Theon a teacher of mathematics at the great Museum.

A sober and serious young woman she was encouraged by her father to devote herself to study and follow in his footsteps. She was eager to do so and dedicating herself to her work she was already teaching mathematics when barely out of puberty, but this alone wasn’t enough it seems.

The Greek philosopher Damascius wrote of her: “Having a nobler nature than her father she was not satisfied with his mathematic instruction but also embraced the rest of philosophy with diligence.”

What she taught was neo-Platonism the one truth, the intellectual, the mystical, and yes the optional; the notion that reality exists in the idea of the object and not the object itself. Her teachings would bring her into conflict with the Christian Church and its insistence on the principle of doctrinal unity.

She was also a keen inventor and when she wasn't teaching, she could always be found in her workshop and has been credited by some (though not by others) with inventing the plane astrolabe an astronomical instrument that charted the celestial bodies and was used in navigation, the hydrometer that was used to test the density of liquids and the hydroscope. Whether she was involved in their creation remains uncertain, but she certainly wrote commentaries upon them and both understood and taught their use.

Her reputation as a creative and original thinker soon spread and people travelled from miles around to hear her speak and to participate in her classes. As Scholasticus wrote: “She explained the principles of philosophy to her listeners many of who came from a great distance to hear her.” But this wasn't supposed to be and her success brought her not only admiration but also the envy of a great many men of influence.

Described as being shapely and of good features men found her attractive not that she was one to use her femininity to her advantage. She would often go barefoot and rejected female clothing for the traditional cloak and attire of the male philosopher. She also spurned any opportunities for love.

When one of her students declared his undying love for her, she responded by showing him a bloody rag, the result of her menstruation. Holding it up to him she said: “Is this what you love, young man? Beautiful, isn't it." He fled in horror.

On account of her gender Hypatia's life was not only controversial but political. In a male dominated world where women were expected to conform, she refused to do so or remain silent. She was not willing to be cowed by public perceptions of inferiority and being brash, confident, and out-spoken only added fuel to the burning embers of resentment.

Alexandria was a bustling port city, densely populated with people of all races and beliefs as well as a place of great learning where tensions often ran high. Never less than volatile it was a place which during Hypatia's time was torn apart by political and religious dispute.

A party of Christian Zealots led by the Patriarch Cyril vied for political power with the Pagan Establishment. Hypatia was a fellow pagan and close friend of the Roman Governor Orestes. She addressed the people in his support: “All formal dogmatic religions are fallacious and must never be accepted by self-respecting persons as final.”

It was clear where she stood on the issue of religion and the Christian Church – faith was a matter of personal conscience and not the domain of priests and scripture.

The Patriarch Cyril was not only jealous of Hypatia’s reputation but critical of her behaviour which he believed undermined society by raising women above their proper station. He also feared her influence. She thought that she could live on equal terms with men, and this was simply unacceptable.

A Christian opponent of Hypatia’s wrote: "In Alexandria there appeared a female pagan philosopher named Hypatia, who was devoted at all times to magic and beguiled people with her satanic wiles." Propaganda was circulating that she was nothing less than a witch and a willing servant of the Devil.”

The case against her in Christian eyes was growing for not only did she behave beyond the bounds of acceptability for any woman but her support for Orestes against the Patriarch Cyril was helping prevent Christian encroachment on secular prerogatives.

She was an impediment to Alexandria becoming a fundamentalist Christian city - she had to be made an example of.

Hypatia would often travel around the city in her chariot and one evening after a busy day attending lectures and visiting friends, she returned home to find a crowd congregated outside her home. This wasn't as unusual as it might seem for her reputation was such that admirers often gathered merely to get a glimpse of her. Even so, on this day the numbers appeared greater than usual, and it was said that when Cyril learned of this ‘his soul was bitter with envy.’

But the rumour had recently spread that Hypatia was a sorceress who had cast a spell upon Orestes and made him her slave and not all those who awaited her arrival were the admirers she was used to.

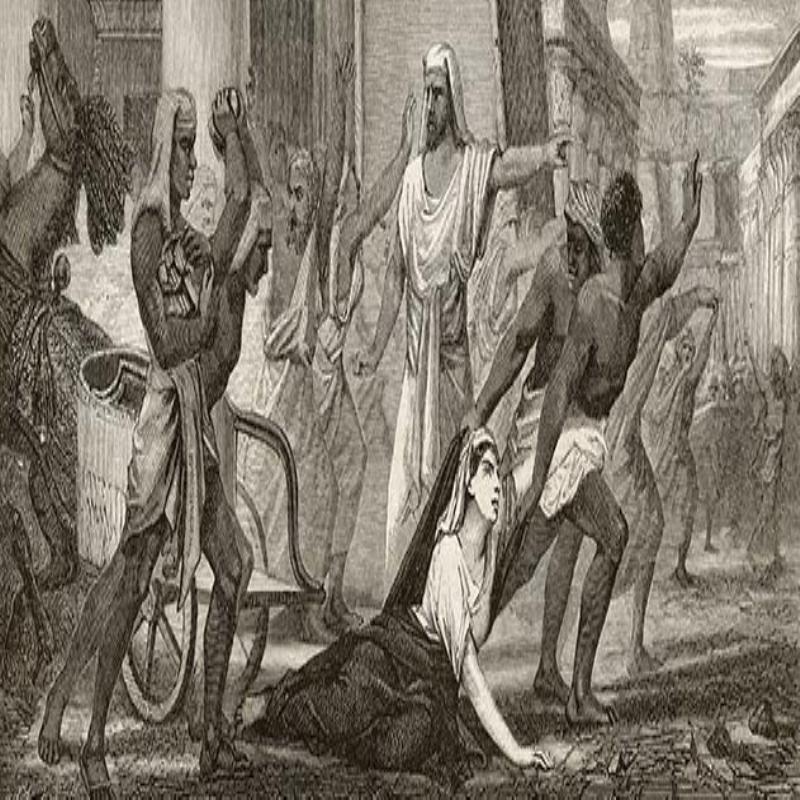

As she pulled up a group of young men emerged from the crowd pulled her from her chariot, forced her to the ground and stripped her naked before dragging her through the streets of the city to the Church of Caeserium. Damascius described events: “Many close-packed ferocious men, truly despicable, fearing neither the eye of the Gods nor the vengeance of men rushed at her and killed her.”

It was indeed a brutal and vicious assault as bound and helpless Hypatia was beaten with rocks before barely alive being taken back onto the streets once more and literally torn limb from limb. The various parts of her body distributed around the city as a warning not only to her fellow pagans but women who dared to challenge the patriarchy.

Her murderers according to Scholasticus had ‘inflicted a very great pollution and brought shame upon their homeland.’

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval, Women

Share this post: