Jack the Ripper: The Women

Posted on 11th January 2021

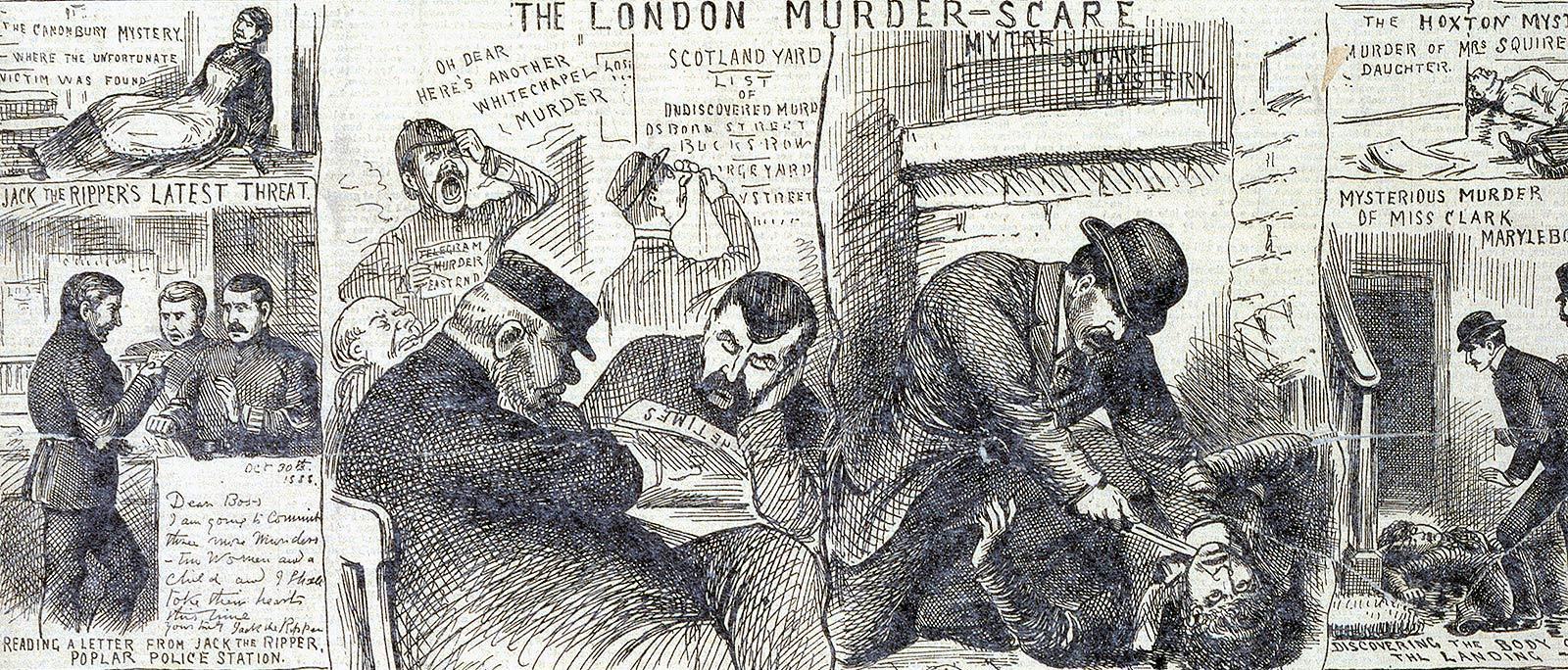

Most people are aware of the crimes of Jack the Ripper, the most notorious serial-killer in history. They were widely reported at the time and have been the subject of numerous books, movies, and investigations ever since, but what do we know of his victims? Their names are familiar to us now because of the gruesome circumstances of their deaths but we too readily forget that they were people too, who lived and loved, had dreams and ambitions, endured pain, and felt loss.

This is the story of the women who became victims of Jack the Ripper.

Mary Anne Walker, better known as Polly Nicholls, was born in Fleet Street near Whitechapel on 26 August 1845, into a respectable working-class family with her father in regular employment as a skilled locksmith.

Aged 19, Polly married a printer by the name of William Nichols by whom she had five children and as far as we can tell they were happily married for the best part of sixteen years. However, in 1880, for reasons that are uncertain their marriage broke down and they separated. For a time, William continued to provide Polly with a small weekly allowance but this was withdrawn once he learned that she had been living with another man. Not long after this the other man moved out and Polly, who may by this time already have been drinking heavily, was left destitute. She lost her home and for a time returned to live with her father, but her drinking put undue strain on their relationship, and she was forced to move out. She was to spend the rest of her life moving from one doss house to another.

Polly kept it secret, certainly from her family at least, that she was from time to time reduced to selling her body to make ends meet; yet despite the drinking and the harsh conditions of her environment having taken its toll at a petite 5’2″ with brown eyes and dark hair greying slightly at the temples those who knew her said she still had some prettiness about her and could pass for a woman ten years younger.

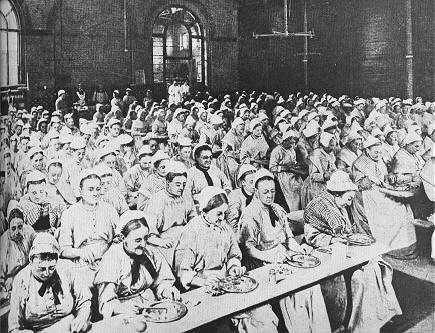

By April 1888, she was an inmate at the Lambeth Workhouse who the following month, as was common in those days, procured for her a position as a domestic servant in a well-to-do house. Polly was delighted to have found work and on 12 May wrote to reassure her father:

“I just write to say that you will be glad to know I am settled in my new place, and going alright up to now. My people went out yesterday and have not returned, so I am left in charge. It is a grand place inside, with trees and gardens back and front. All has been newly done up. They are teetotalers and religious so I ought to get on. They are nice people and I have not much to do.”

Her father was relieved to learn that she was properly employed once more but it wasn’t to last and in July, she was dismissed from her post following an accusation of theft.

Polly was unable to find another job, and by the late summer she was living in the Thrawl Street Lodging House, Spitafields, and unable to pay the rent. On the night of 30 August, she told the Lodging Housekeeper: “I’ll soon get my doss money – see what a pretty bonnet I have.”

At around 11.30 pm she was seen walking the Whitechapel Road. An hour later she left a pub in Brick Lane and returned to the Lodging House in Thrawl Street but was refused admittance because she was still four pence short of her rent. At 2.30 am she met Emily Holland, a fellow prostitute and a woman with whom she had previously shared a room and told her: “I had my doss money three times today and spent it.”

Emily was later to say that Polly had been very drunk and unsteady on her feet. It was the last time she was seen alive.

At 3.40 am her body was discovered in Bucks Row just 150 yards from the busy London Hospital by Charles Cross, a cart driver who as on his way to work. He kept his distance and unaware whether she was dead or alive walked on later informing a passing policeman. Upon inspection it became evident that Polly’s throat had been cut. Her dress had also been pulled up and her abdomen mutilated.

The policemen present interviewed several horse slaughterers who had been working nearby but they reported that they had not seen or heard anything. She had in her possession just a comb, a pocket handkerchief, and a broken piece of mirror.

Polly Nichols, aged 43, had become Jack the Ripper’s first acknowledged victim.

Annie Chapman was born Anne Eliza Smith in London sometime in 1841. She was the daughter of an ex-soldier who was rarely out of work and had three sisters and a brother with whom she had a fractious relationship, in particular her sisters.

In May 1869, she married a coachman, John Chapman and together they had three children, one died young, another was disabled, and the third left home whilst still an adolescent. The death of their youngest child, a daughter, had affected them both badly and their relationship was never the same after the tragedy.

In early 1884, they separated and two years later Annie moved to Whitechapel where she lived with a man. Little is known of him except that he appeared to have no gainful employment other than occasionally making wire sieves. But as Annie was in receipt of a 10 shilling a week allowance from her husband, she was relatively well-off; her allowance ceased however when John Chapman died of alcohol poisoning on Christmas Day, 1886. Upon learning of this the man, she had been living with abandoned her.

Annie, who had a reputation for being argumentative and difficult had always been a sensitive and emotional woman greatly affected by loss and even though she and her husband were separated they had remained friends and his death hit her hard. Indeed, a friend of Annie’s was later to remark that she appeared to give up on life at that point.

Annie fell into a deep depression and her drinking, which had always been heavy, if intermittent, began to spiral out of control.

By 1888 Annie, known as “Dark Annie” because of her dark brown hair and not for her sullen mood swings as has often been thought was living in the various Lodging Houses that dotted the area of the East End, sometimes with a labourer named Edward Stanley, who was known locally as The Pensioner. She did crochet work for neighbours and sold flowers, but she had also turned to prostitution when money was tight.

Described as being industrious and civil when sober, she was nonetheless often the worst for wear. Though many of her friends were to deny this following her death describing her as a “Sober, and steady going woman who seldom took any drink,” there is much evidence to show that this was not the case, and it is possible that when she drank, she did so heavily and was careful about whom she did her drinking with.

In the week prior to her death, she had a fight with another woman, Eliza Cooper, over a borrowed bar of soap that she had not returned and as a result was carrying a number of bruises that had still not yet healed. It led some to remark that she must have taken quite a beating.

At 1.45 am on 8 September, Annie left her Lodging House much like Polly Nichols had done before to earn the money to pay for her board. A woman, Elizabeth Long, later described how she saw Annie around 5.30 am talking to man she said was of medium height, dark complexioned, possibly foreign, and of a shabby genteel appearance. Just 30 minutes later at 6.00 am her body was found lying in the doorway of 29 Hanbury Street, Whitechapel, by a market porter named John Davis.

None of the sixteen residents of the house had heard anything, though a carpenter named Albert Cadosch who worked nearby claimed that he had heard a woman shout No and then a loud thud.

Annie had been strangled before having her throat cut and just like Polly Nichols her clothes had been disturbed and her lower body mutilated. The doctor who examined the body was to say that the killer, whoever he was, must have had some anatomical knowledge.

Prior to her murder she had often complained of feeling unwell and was later discovered at the autopsy to be suffering from tuberculosis. She had in her possession only two small combs, a scrap of muslin, and an envelope containing some pills.

The 47-year-old Annie Chapman was to be Jack the Ripper’s second victim.

Elisabeth Gustafsdottir was born in Gothenburg, Sweden in 1843, the daughter of a farmer and unlike the other Ripper victims who had taken to selling their bodies after the break-up of a marriage or having fallen into poverty she had worked as a prostitute from an early age.

On 21 April 1865, she gave birth to a stillborn baby and later that same year she was treated for venereal disease and formally registered with the police as a working prostitute.

On 10 July 1866, she moved to London. Her precise reasons for doing so remain unknown but it is possible that she had either found a job, already had relatives living in England, or was simply evading the law. In 1869, she married a ship’s carpenter, John Stride, and for seven years they were to run a coffee shop in Poplar, East London but by March 1877, it appears that they were no longer together for she was admitted alone to the local Workhouse.

Liz appears to have been greatly affected by the loss of her baby, and in later years she was to frequently claim to be the mother of children she’d never had. Indeed, she had the reputation of being a fantasist. For example, she would tell the story of how she had lost her husband and two of her nine children in the sinking of the pleasure steamer Princess Alice on the River Thames. They had drowned whilst she had only survived by climbing the mast as the boat sank; and her often pronounced stutter had been induced by being kicked in the mouth in the panic that ensued.

The truth was that John Stride died of tuberculosis in the Poplar Sick Asylum on 24 October 1884, six years after the Princess Alice disaster.

Long Liz, so-called for her height, though she was only tall by the standards of the day had dark curly brown hair which she wore long, a pale thin face, and blue sometimes grey eyes. She was described as calm, quietly spoken, almost shy in fact, though she had been arrested numerous times for being drunk and disorderly, and she was evidently intelligent, or at least quick to learn for she was fluent in both English and Yiddish.

From 1885 she was seen frequently in the company of Michael Kidney, a dockyard worker. Their relationship was a volatile one and she once accused him of assault and reported the incident to the police, though she subsequently withdrew the charge. He would later describe how she would often disappear for days sometimes weeks on end and how he assumed she was drinking again.

By the summer of 1888 she was living at the Lodging House in Flower and Dean Street, Whitechapel, living off whatever she could make sewing and cleaning, and the charity of the Church of Sweden in London.

Doctor Thomas Barnado who was doing charity work in the area at the time and was soon to open his famous home for destitute young men described how he saw Liz discussing the Ripper murders with the other women in the kitchen of the Lodging House. He said they appeared very scared and overheard one of them say: “We’re all up to no good, and no one cares what becomes of us.”

They feared one of them would be next.

Liz was to spend most of the day of the 29 September cleaning rooms at the Lodging House for which she was paid 6d.

The day had been a miserable one with a lashing rain and a strong wind blowing but even so by the time night came Liz was to be seen by many people working the narrow streets and dark alleys of Whitechapel. At 11.00 pm she was seen by James Brown talking to a short man who was barely as tall as she was in a morning suit and bowler hat in Berner Street. Brown claimed that he heard Liz say – “No, not tonight.”

At 12.35 am she was spotted by Police Constable William Smith with a man in a hard felt hat whom he remembered was carrying a package about 18 inches long and wearing a full-length overcoat. This was near the International Working Men’s Club and was to be the last time she was seen alive.

Liz Stride’s body was discovered at 1.00 am on Sunday 30 September by Louis Diemschutz, the steward of the club, in Dutfield’s Yard which was adjacent to where he worked. Her body was still warm, and the blood was gushing from a deep wound to the neck. The killer had evidently been interrupted in his work and Liz’s body had not been mutilated like the Ripper’s other victims. Indeed, Diemschutz was to say that he could sense the presence of the killer still in the yard.

“Long Liz” had on her only a comb, a key for a padlock, a metal spoon, and some scraps of muslin and paper.

Elizabeth Stride was the Ripper’s third victim but only the first that night for less than an hour later and just half-a-mile away he was to strike again.

Catherine Eddowes: the Ripper’s second victim on that ghastly night was born on 14 April 1842, in Wolverhampton but her family were later to settle in London.

As a young woman Catherine was to return to Wolverhampton to work in a factory stamping tin plates where friends described her as being a very good looking and jolly sort of girl. Whilst there she lived with an ex-soldier named Thomas Conway with whom she had three children out of wedlock. They returned to London, but it appears that she was already estranged from her family for she had little contact with them thereafter. This may have been because of her refusal to marry which was the cause of some shame at the time.

At barely five feet tall, Catherine had auburn hair, hazel eyes, and a tattoo on her forearm with the initials TC, for Thomas Conway, though their love had long since died. So much so that he now drew his army pension under a false name so that she could not trace him and kept the address of their children secret from her.

She was said to be an educated woman who was well able to read and write, an amiable lady with a ready smile who liked to laugh and sing. But this was when she was sober. Under the influence of alcohol, it was said her mood changed and she would become abusive and physically aggressive. Her fierce temper when drunk was to be avoided.

By the mid-1880’s she was living in the doss houses of Whitechapel sometimes with a man known as John Kelly. They were so poor that at one point Kelly had been forced to pawn the only pair of boots he possessed.

During the summer of 1888, she went hop picking with Kelly returning to London in September. Staying briefly at the Casual Ward, a shelter for the homeless where they could also receive rudimentary medical treatment, she told the Superintendent that she had returned to London to get the reward for the apprehension of the Whitechapel murderer. I think I know who he is. That she truly said such is anecdotal only though future events provide it with some credence.

By the end of September, she was living in the same Lodging House on Flower and Dean Street as Liz Stride and the fact that both women were to be killed within minutes of each other leads one to think that the killer may indeed have been known to them.

On the night of 29 September at around 8.30 pm, she was discovered lying blind drunk in Aldgate High Street by Police Constable Louis Robinson and was taken into custody at Bishopsgate Police Station to sober up. She was deemed sober enough to leave by around 1.00 am the following morning but she wasn’t released until she provided the police with her name which she said was Mary Anne Kelly, an interesting choice of alias as the final victim of the Ripper was to be Mary Kelly. She then headed off back towards Aldgate and was last seen alive at 1.35 am in Mitre Square not far from the Great Synagogue of London.

At 1.45 am her body was discovered in Mitre Square by Police Constable Edward Watkins who had passed by there only 15 minutes earlier.

The killer must have worked quickly again leading some to believe that he must have had some anatomical knowledge. Her throat had been cut and her face repeatedly slashed. Her clothes had been drawn up above her abdomen and her uterus and kidneys had been removed and taken. Her intestines had also been torn out and draped over her right shoulder in a very deliberate manner. Near the murder scene was found the notorious graffiti “the Juwes are the men that Will not be Blamed for Nothing” scrawled on a wall.

The Police Commissioner Sir Charles Warren fearing that if news of the graffiti became public the murders would be construed as part of a Jewish Blood Ritual had it removed immediately. It had after all, been scrawled near the Synagogue and he believed it was likely anti-Semitic propaganda intended to stir up trouble in the East End.

Catherine was a woman who clearly feared losing the few possessions she had for she always carried them with her. On her body were found two clay pipes, a tin containing tea, a tin containing sugar, an empty matchbox, a red flannel with pins and needles attached, a ball of hemp, a number of buttons and a thimble, six pieces of soap, a teaspoon, a table knife, and a tin with two pawn tickets in it.

Catherine Eddowes was the Ripper’s fourth victim and the nature of her injuries convinced the police for the first time that they were hunting a sexual sadist. This was to be confirmed by events but for a period at least the panic that had gripped the East End relented as the killing ceased.

Mary Jane Kelly, the Ripper’s last confirmed victim unlike the others who were all middle-aged was still in the full bloom of youth. She was a tall, blue-eyed redhead whom Police Inspector Walter Dew, who was later to become famous as the man who arrested Dr Crippen, described as being: “A pretty, buxom, young girl who was never seen without a clean white apron and rarely wore a hat, she was very proud of her long red hair.”

She is believed to have been born in Limerick, Ireland, sometime in 1863, but her family moved to Wales soon after her birth and she was raised in Caernarfonshire where she became a fluent Welsh speaker. It was when she moved to Cardiff to live with a cousin that she first turned to prostitution.

In 1884, aged 21, she moved to London where she worked in an upmarket West End brothel servicing the better kind of gentleman. But she soon started to drink heavily and as a result lost her job ending up in the less salubrious East End where she met a fish porter, Joseph Barnett, with whom she set up house. As long as Barnett was in employment, Mary remained off the streets, and they appeared to be happy together. However, Barnett was soon accused of theft and lost his job as a result.

With no money coming in Mary insisted that she return to prostitution to guarantee them an income. They argued furiously over this and Barnett, declaring that he refused to live in a brothel, moved out of the house. Despite this, they were to remain friends and following her death Barnett was always to speak of her with great affection saying that she was “an excellent scholar and an artist of no mean degree,” though he was to say later at her Inquest that he would read the newspaper to her, indicating that she may have been illiterate.

Mary Kelly was well known locally for being raucous, loud, and always in search of fun. When drunk she would sing Irish folk songs which lent her a certain charm. But she could also be abusive and sharp-tongued which led some of her friends to name her “Black Mary.”

At about 11.45 pm on the night of 8 November, Mary was seen returning to her home at 13 Miller’s Court, Whitechapel by another prostitute and resident Mary Anne Cox who said she was drunk and with a stout ginger-haired man. They went into her room together and for a time she could hear Mary singing.

At 2.00 am, a labourer George Hutchinson, who knew Mary, said that she had approached him and asked to borrow some money. He said she was with a man of Jewish appearance of whom he was to provide the police with a detailed description. Hutchinson, however, was a strange man who was dismissed by the police as a fantasist. Indeed, he was later to confess to being Jack the Ripper but on this occasion there were others who could prove he had been elsewhere.

Hutchinson may not have been Jack the Ripper, but he was obsessed with Mary Kelly and was undoubtedly a stalker. He told the police that he followed the couple back to Mary’s home and kept watch for about 45 minutes. He was suspicious because he felt the man seemed rather well-heeled for the area.

By 3.00 am, Mary’s home was in darkness. Some local people later reported hearing screams during the night and faint cries of Murder! Murder! But such cries in the East End in the early hours of the morning were not unusual and few people paid any attention to them.

At around 10.45 on the morning of 9 November, Thomas Bowyer visited 13 Miller’s Court to collect the rent. Mary was six weeks in arrears and her landlord was beginning to lose patience. He knocked repeatedly upon the door but receiving no response he pulled aside a coat that she had been using as a curtain and peered inside. What he saw horrified him, turned his stomach, and for a few moments he could barely breathe or stand up. He had previously served as a soldier in India, but he had never seen anything like this.

Mary’s bedroom had the appearance of a slaughterhouse. She was lying naked upon her bed; her throat had been cut and her face slashed beyond recognition. Her breasts had been cut off with one placed under her head. Her uterus, kidney, liver, spleen, and intestines had been removed and positioned at various places around her body. Flesh from her abdomen and thighs had been stripped away and placed on the bedside table. Pieces of flesh hung from the walls.

The police who visited the scene had never witnessed an attack carried out with such ferocity. Dr Thomas Bond, who examined the body, concluded that it would have taken at least two hours to carry out the mutilations. As a result, the police took photographs of Mary’s eyes in the hope that the retina had retained the image of her killer.

The room itself was awash with blood and the killer had started the fire which had been so intense that it had charred the grate and the nearby walls. He had burned Mary’s clothes, and quite possibly his own, which would have been soaked in blood. The door had also been locked from the inside and the police had had to break in.

The police were at a loss what to do. Humiliated by their failure to find such a dangerous sexual maniac they now feared riots on the streets of the East End and a possible anti-Semitic backlash in what was a predominantly Jewish area of London. They waited nervously for reports of the next attack, but it never came.

With the murder of Mary Kelly, the Jack the Ripper attacks ceased.

The attack upon Mary Kelly had been of the obscenest ferocity and sustained over a long period of time. Did the murders then cease because it signified the culmination of a maniac’s lust for blood, or had Mary been singled out for such special treatment? Had the killer perhaps himself died mysteriously soon after the murder? These things we cannot know as he was never caught, and the identity of Jack the Ripper has never been uncovered or revealed.

What we do know for certain was that the women he killed were people and not just victims. They had been wives and mothers and, in most cases, had previously lived respectable lives before falling upon hard times due to circumstances, perhaps of their own making, perhaps not. Like many before and since they tried to find solace in the bottle, but alcohol is not and never will be the elixir of redemption. It was to help propel them to a brutal and violent end to what had been in large part a miserable life.

However, we do these women, and history, a disservice to remember them just as victims and not as human beings.

Tagged as: Victorian

Share this post: