Jacques-Louis David: The Devil's Playground

Posted on 21st November 2021

Jacques-Louis David was a great artist but not a great man, but then how often can we say that. Afflicted with a facial tumour, the result of a sword cut that impaired his speech he communicated through his art the confident strokes of his brush belying the nervous stammer of his being. He was to live through tumultuous times which he captured on canvass like no other artist of his day – and he was a chameleon who would change according to the political weather - first the painter of Republican virtue, then of Revolution and Terror, and finally of Dictatorship. Finally, the French people would tire of him, and he would exile himself to Belgium which is exile indeed.

He was born in Paris on 30 August 1748, into a wealthy family who despite the death of his father in a duel ensured that he was well cared for by his uncle, a successful architect. He received the best education available but rejected the opportunities for advancement this provided to pursue his desire to be an artist. His family did not stand in his way, and he studied under both Francois Boucher and Joseph-Marie Vien before attending the Royal Academy. His favoured genre was the neo-classical – it would take him a long way.

Looking to Classical Antiquity and Ancient Rome for inspiration the themes he undertook of Republican virtue, mordant self-sacrifice and an honourable death suited well the political mood of the moment, big ideas painted on big canvasses – The Oath of the Horatii, The Death of Socrates, The Lictors Bringing to Brutus the Bodies of his Sons and so forth would quite literally make people gasp in admiration. Here was someone they believed, steeped in history and understanding who, could capture the momentous events of their time for all eternity. He was one of them he was a man who could be trusted. But he was never that.

David embraced they revolution with a ferocious insincerity, he had early in his career taken commissions from those he would later condemn before their date with the National Razor but was now both a Jacobin and advocate of the Terror. He was even elected a Deputy and would for a brief time serve as President of the National Convention.

A friend and supporter of Maximilien Robespierre he voted for the execution of the King and frequently referred to his Queen Marie Antoinette as both a whore and a witch. When his ally Jean-Paul Marat, the journalist and man for whom there could never be too much blood, was assassinated in his bath by Charlotte Corday the cry for him to immortalise the Great Denunciators martyrdom on canvass was deafening. He didn’t disappoint working in haste and in great heat before a decaying corpse to capture for all time the moment of his death. When he presented his painting before his fellow Deputies in the Convention he spoke thus: “Citizens, the people were again calling for their friend; their desolate voice was heard. David take up your brushes, avenge Marat! I heard the voice of the people. I obeyed.”

The Death of Marat is David’s most famous painting and would prove the pinnacle of his career, but it was also his most controversial and dangerous. Now firmly wedded to Robespierre and the Terror he could not avoid the fall-out from their demise.

When on 9 Themidor (27 July 1794) Robespierre was attacked in the National Convention which then voted for his arrest David was heard to shout in defiance: “Robespierre, if you drink hemlock then I shall drink it with you.” His apparent determination to share his hero’s fate was short-lived however, for by the time they came for him a few days later he had changed his mind. It was Robespierre who had been the tyrant he was just an artist. He was to be imprisoned nonetheless not once but twice but would be spared the guillotine.

It had been a brush with death he had neither expected nor enjoyed. He would return to painting, but he was done with politics; no longer the painter of Revolution he nonetheless remained an artist of repute and the commissions rolled in but it seemed his time as a man of substance has passed. He would rise again however and this time upon the shoulders of another dictator, Napoleon Bonaparte.

David was again mixing with the great and the good this time as the arch-propagandist for the French Emperor who would soon rule much of Europe but when he too was deposed and the Bourbons restored to the throne David was added to the proscribed list as one of those who had voted for the execution of the old King. Fearing for his life he chose exile in Belgium rather than await events. No great attempt was made to compel the return to France of its greatest living artist.

David continued to paint of course, and teach, but his time was done. He died on 29 December 1825, aged 77, much admired but little loved and even less missed.

The Oath of the Horatii

The Lictors Bring to Brutus the Bodies of his Sons

Death of Socrates

Mourning Homer

Death of Seneca

Mars Being Disarmed

Intervention of the Sabine Women

Tennis Court Oath

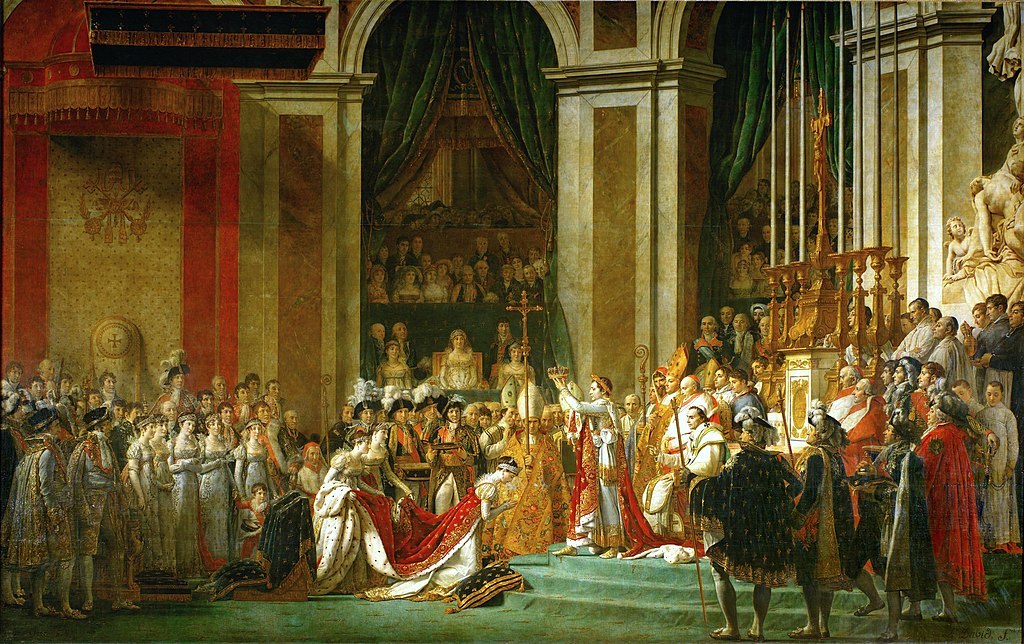

Napoleon Bonaparte’s Coronation

Napoleon Bonaparte in his Study

St Bernard Pass

Genevieve Pecoul

Henrietta Delacroix

Pierre Seriziat

Tagged as: Art

Share this post: