John Evelyn & Samuel Pepys: Diary Extracts

Posted on 2nd February 2021

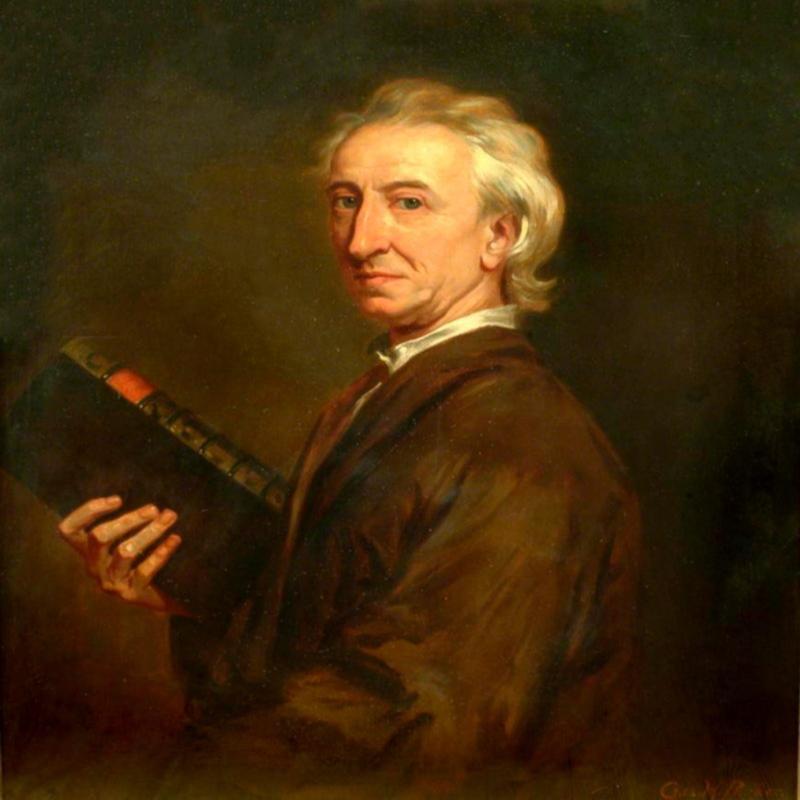

John Evelyn is one of England’s most notable diarists, though less famous that his contemporary Samuel Pepys the longevity of his diaries and journals which he maintained throughout his adult life and spanned near sixty years are quite extraordinary.

He was born on 31 October 1620 in Wooton, Surrey, to a wealthy family who had made their fortune in the production of gunpowder and had since become local landowners. A High Church Anglican he was also a fervent Royalist who upon the outbreak of the Civil War briefly volunteered in the Royalist Army but it only took a small but bloody skirmish at Brentford just outside London to convince him that he did not have the stuff of a soldier and he sailed to Europe where he embarked upon a cultural tour, married Mary Browne, the daughter of the English Ambassador in Paris, and sat out the duration of the war.

Upon his return to England in 1652, he settled in Deptford. Never short of money, even during his self-imposed exile on the Continent, he was freed of the need to find gainful employment and could instead indulge his intellectual pursuits. He was to become an enthusiastic designer of gardens and on 28 October 1660 a founder member of the Royal Society where he was to make the acquaintance of such notable people as Robert Hooke, Christopher Wren, and Sir Isaac Newton. He was also to become good friends with his fellow diarists and Royal Society member, Samuel Pepys.

He was to continue to record events in his diary until just two weeks before his death on 27 February 1706, at the age of 85.

January 1649: The villainy of the rebels proceeding now so far as to try, condemn, and murder our excellent King on the 30th of this month, struck me with such horror, that I kept the day of his martyrdom a fast, and would not be present at that execrable wickedness; received the sad account of it from my brother George, and Mr Owen.

28 October 1653: Went to London to visit my Lady Gerrard, where I saw that cursed woman called the Lady Nolan, of whom it was reported that she spit in our King’s face as he went to the scaffold. Indeed, her talk and discourse was like an impudent woman.

4 December 1653: Going this day to our Church, I was surprised to see a tradesman, a mechanic, step up; I was resolved yet to stay and see what he would make of it. His text from Samuel XXIII And Beniah went down and slew a lion in the midst of a pit in a time of snow; the purport was that no danger what to be thought difficult when God called for shedding of blood, inferring now that the Saints were called to destroy temporal governments; with such feculent stuff; so dangerous a crisis were things grown to.

9 August 1654: To the old and ragged city of Leicester, large and pleasantly seated, but despicably built, the chimney flues like so many smiths forges; however, famous for the tomb of the tyrant Richard III, which is now converted to a cistern from which (I think) cattle drink.

3 September 1658: Died that arch-rebel Oliver Cromwell, called Protector.

29 May 1660: This came in his Majesty Charles the 2d to London after a sad and long exile and calamitous suffering both of the King and Church; being 17 years. This was also his Birthday, and with a triumph of above 20,000 horse and foot, brandishing their swords and shouting with inexpressible joy; The ways strewn with flowers, the bells ringing, the streets hung with tapestry, fountains running with wine . . . I stood in the Strand and beheld it and blessed God; and all this without one drop of blood, and by that very army, which rebelled against him.

11th October 1660: The regicides, who sat on the life of our late King, were brought to trial in the Old Bailey, before a commission of oyer and terminer.

17th October 1660: Scot, Scroop, Cook, and Jones suffered for the reward of their iniquities at Charing Cross, in sight of the place where they put to death their natural Prince. I saw not their execution, but met their quarters, mangled, and cut, and reeking, as they were brought from the gallows in baskets on the hurdle. Oh, the miraculous providence of God!

4th September 1666: The burning still rages, and it was now gotten as far as the Inner Temple; all Fleet Street, the Old Bailey, Ludgate Hill, Warwick Lane, Newgate, Paul’s Chain. Watling Street, now flaming, and most of it reduced to ashes; the stones of St Paul’s flew like grenades, the melting lead running down the streets like a stream, and the very pavements glowing with fiery redness, so as no man or horse was able to tread on them, and the demolition had stopped all passages, so that no help could be applied.

Samuel Pepys is the most famous diarist in the English language yet he only maintained a detailed account of his life for nine years between 1660 and 1669. His final entry makes clear that he feared for his eyesight and would in future have all his papers read to him. Yet during that short period he was to provide us with graphic accounts of such momentous events as the Restoration, the Plague, and the Great Fire of London as well as an insight into the full, sometimes troubled, often ribald life of a man of import and property in seventeenth century London with a clarity and honesty that can still take one's breath away.

21 March 1660: In our way the coach drove through a lane by Drury Lane, where abundance of loose women stood at the doors, which, God forgive me, did put evil thoughts in me but proceeded no further, blessed be God.

23 May 1660: Upon the quarter-deck (the King) fell in discourse of his escape from Worcester. Where it made me ready to weep to hear the stories he told me of his difficulties that he had passed through. As his travelling four days and three nights on foot, every step up to the knees in dirt, with nothing but a green coat and a pair of country breeches on and a pair of country shoes that made him so sore all over his feet that he could scarce stir.

13 October 1660: To Charing Cross today to see Thomas Harrison hung, drawn, and quartered. He looked as cheerful as any man could in that condition. He said he was shortly to be at the right of Christ to judge them who had judged him. Thus it was by chance to see the King beheaded at Whitehall and the first blood-shed in revenge for the blood of the King at Charing Cross. Within all afternoon setting up shelves in my study.

7 June 1665: “ . . . it being the hottest day that I ever felt in my life, and it is confessed so by all other people the hottest day the beginning of June we to the New Exchange and their drunk wine with much entreaty getting it for our money, and would not be entreated to let us have one glass more . . . This day much against my will, I did in Drury-Lane see two or three houses marked with a red cross upon the doors and Lord have mercy upon us writ there which was a sad sight to me, being the first of that kind that to my remembrance I ever saw. It put me into an ill-conception of myself such that I was forced to buy some roll tobacco to smell and chew which took away the apprehension.

25 October 1665: " . . . and so to Church, and there find Jack Fenn come with his wife, a pretty black woman: I never saw her before, nor took notice of her now. So home and to dinner . . . to have my hair combed by Deb, which occasioned the greatest sorrow to me that I ever knew in this world, for my wife coming up suddenly did see me embracing the girl with my hand under her coats, and indeed I was with my main in her cunny. I was at a loss upon it and the girl also . . . but after much crying and reproaching me with inconstancy and preferring a sorry girl before her. I did give her no provocation but promise all fair usage to her and love, and foreswore any hurt that I did with her, till at last she seemed to be at ease again, and towards morning a little sleep.”

2 September 1666: I down to the water-side, and there got a boat and through bridge, and there saw a lamentable fire. Poor Michell's house, as far as the Old Swan, already burned that way, and the fire running further, that in a very little time it got as far as the Steelyard, while I was there. Everybody endeavouring to remove their goods, and flinging into the river or bringing them into lighters that layoff; poor people staying in their houses as long as till the very fire touched them, and then running into boats, or clambering from one pair of stairs by the water-side to another. And among other things, the poor pigeons, I perceive, were loth to leave their houses, but hovered about the windows and balconys till they were, some of them burned, their wings, and fell down. Having staid, and in an hour's time seen the fire: rage every way, and nobody, to my sight, endeavouring to quench it, but to remove their goods, and leave all to the fire, and having seen it get as far as the Steele-yard, and the wind mighty high and driving it into the City; and everything, after so long a drought, proving combustible, even the very stones of churches, and among other things the poor steeple by which pretty Mrs.———— lives, and whereof my old school-fellow Elborough is parson, taken fire in the very top, and there burned till it fell down.

2 September 1666: Hurried to St Paul’s, and there walked along Watling Street, as well as I could, every creature coming away laden with goods to save here and there, sick people carried away in beds. Extraordinary goods carried away in carts and on backs. At last I met my Lord Mayor in Cannon Street, like a man spent, with a handkerchief around his neck. To the King’s message he cried like a fainting woman, Lord, what can I do? I am spent; people will not obey me. I have been pulling down houses, but the fire overtakes us faster than we can do it. So he left me, and I him, and walked home.

4 September 1666: Sir William. Penn and I to Tower-street, and there met the fire burning three or four doors beyond Mr. Howell's, whose goods, poor man, his trays, and dishes, shovels, &c., were flung all along Tower-street in the kennels, and people working therewith from one end to the other; the fire coming on in that narrow street, on both sides, with infinite fury. Sir W. Batten not knowing how to remove his wine, did dig a pit in the garden, and laid it in there; and I took the opportunity of laying all the papers of my office that I could not otherwise dispose of. And in the evening Sir W. Pen and I did dig another, and put our wine in it; and I my Parmazan cheese, as well as my wine and some other things.

Tagged as: Fact File, Tudor & Stuart

Share this post: