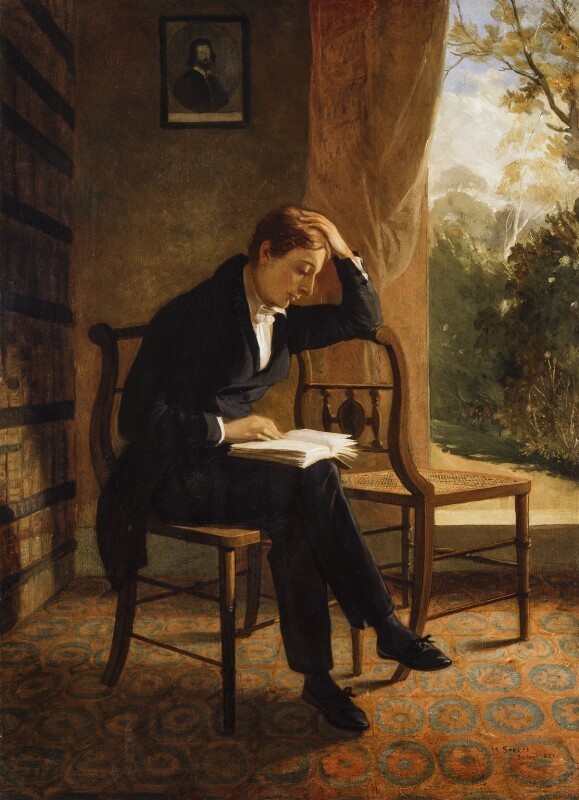

John Keats: Too Beautiful to Live

Posted on 14th February 2021

Often laid-low by a disease that kills John Keats was a man living on borrowed time.

Tuberculosis or consumption as it was known was the illness that took the life of his mother and two of his brothers as well as his own but in the short time available to him he was to write some of the most popular verse in the vast canon of English literature.

Unlike his contemporaries, Shelley and Byron, his was not the poetry of ideas or of revolution and social change but of sense and feeling, imagery and sound, of intimacy and love. His was the minutiae of vast panoramas and along with the King James Bible and the Sonnets of William Shakespeare it transformed the English language into a thing of beauty - it was poetry in its purest form.

He was born in Moorgate, London, on 31 October 1795, the son of an Ostler who worked at the stables attached to the Swan and Hoop Inn and unlike so many of the Romantic Poets he was not the scion of privilege but of relatively humble origins. He would have to work for a living.

The requirement to pay his way was an impediment to his literary ambitions but of scant concern compared to the tragedy and fear that was to be his constant companion.

When he was just eight years of age his father died after falling from his horse and fracturing his skull on his return from visiting John at school and he would be consumed with guilt as a result.

In March 1810, his mother died of the dreaded consumption and John along with his younger siblings was sent to live with their grandmother in Edmonton. She had neither the money nor the wherewithal to cope and so appointed two guardians to take care of them. The young John, who had been doing well at school having already won a first literary prize was at the age of 13 forced to curtail his education and find work. He had in fac two sizeable bequests held in trust for him until his 21st birthday but he was never made aware of either and was to struggle for money all his life. In 1810, aged 15, he got a job as an apprentice at Thomas Hammond’s Apothecary in Edmonton where he lived in the attic above the shop.

In the evenings following work he would indulge his love of literature reading assiduously and writing verse. At this time, he was free of illness and liked nothing more than to walk in the countryside and breathe in the fresh air. It was the happiest time of his life.

Having completed his apprenticeship in October 1815, he registered as a medical student at Guy’s Hospital where he worked as a surgeon’s assistant and expressed the view he wished to train as a doctor. But he had also fallen in love with poetry and was torn between the two.

The medical profession he knew offered him the opportunity of a career and a comfortable life and that there was little money to be made in poetry, but his love of language and words was well known to his friends who encouraged him to keep writing.

In May 1816, the poet Leigh Hunt published the poem ‘O Solitude’ in his magazine The Examiner. It was the first time that Keats work had been exposed to the public gaze. Later that year in October he published his first book of verse simply called - Poems. It was not particularly well received but he remained undaunted, and Hunt continued to publish his work.

Having already spent a great deal of money on his medical training the decision to cease his application to the Royal College of Surgeons filled him with dread but the desire to write poetry was simply too strong. It was not good timing however, for never less than generous he had spent most of his money on family and friend. He was heavily in debt and little of the money he was owed was ever repaid.

In March 1817, he published his second book of poems Endymion to a chorus of bad reviews with the literary critic John Gibson Lockart writing in Blackwods Magazine even going so far as to describe him as an uncouth cockney:

“To witness the disease of any human understanding, however feeble, is distressing; but the spectacle of an able mind reduced to a state of insanity is ten times more afflicting . . . the frenzy of the poems was bad enough in its way, but it did not alarm us half so seriously as the calm, settled, imperturbable drivelling idiocy of Endymion. Back to the apothecary shop Mr Keats, back to plasters, pills, and ointment boxes.”

He went onto accuse him of summoning up - the most incongruous ideas in the most vulgar language. It was little better received elsewhere and his fellow poets Byron, Shelley and Coleridge, always protective of him though he often felt uncomfortable in their presence would, later claim that the bad reviews in Blackwoods, the Quarterly Review and others, had hastened him to his premature death. Indeed, Byron famously remarked that Keats had been - snuffed out by an article.

Despite the criticism he persisted and the following year his faith in his own abilities was to be vindicated by the brilliance of his verse. It was to be the zenith of his career as a poet, but it was also the year when he was diagnosed with tuberculosis and became aware of his own impending death. He began to write as if in frenzy.

Living at the house of a friend Charles Armitage Browne, Wentworth Place on Hampstead Heath his great poems came thick and fast – Ode to the Psyche, Ode to a Nightingale, Ode to a Grecian Urn, Ode to Melancholy, Ode to Indolence, and Ode to Autumn. He had earlier been mocked for being mawkish and sentimental when in fact he had disavowed the mythic grandeur of so much nineteenth century verse for the simple desires of the heart and the pain of unrequited desire – the desire to live.

His energetic and fast-paced style of writing began to remake the traditional understanding of the Ode and the Sonnet. His poetry, increasingly musical in tone had soared to unprecedented heights of lyrical beauty. He wrote of his verse:

“Poetry should surprise by a fine excess and not by singularity, it should strike the reader as a working of his own highest thoughts and appear almost a remembrance.”

In October 1819, he began to compose ‘Bright Star’ one of his most popular and enduring poems:

Bright star, would I steadfast as thou art–

Not in lone splendour hung aloft the night

And watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like nature’s patient, sleepless Eremite,

The moving waters at their priestlike task

Of pure ablution round earth’s human shores,

Or gazing on the new soft-fallen mask

Of snow upon the mountains and the moors-

No - yet still steadfast, still unchangeable,

Pillow’d upon my fair love’s ripening breast,

To feel for ever its soft fall and swell,

Awake for ever in a sweet unrest,

Still, still to hear her tender-taken breath,

And so live ever – or else swoon to death.

Written in sonnet form it has been suggested that it had not been completed before he fell into his final illness and so was perhaps his final work but there is little proof of this other than its theme of love, loneliness, and eternity. Bright Star wasn’t published until 1838, seventeen years after his death. But if his poetry was a dream then his reality was the nightmare.

The previous year his younger brother Tom had fallen ill with tuberculosis and John had spent much of his time nursing him. When that summer he had to abandon a walking holiday in Scotland because of a fever and return to London it was remarked upon how pitifully thin he was. It was evident that he too was ill. The devastation of Tom’s death on 31 December 1818, only served to weaken him further.

John Keats was to have two great loves in his life Isabella Jones and Fanny Brawne though whether either relationship was ever consummated remains uncertain.

Isabella Jones is a somewhat shadowy figure about who little is known. Keats had met her on a journey to the village of Bo Peep in Kent in May 1817. They shared a common background in that she was the daughter of an Innkeeper. She was described as well-educated, pretty and coquettish. She became one of his closest friends and was to be the focus of much of the love interest in his best regarded poems. Though we do not know how their relationship developed Keats did write to his brother George that he frequented her rooms, kissed, and was warmed by her.

A strikingly beautiful eighteen-year-old she charmed Keats who fell in love upon first setting He first came to know Fanny Brawne in September 1818, whil she too had lodgings in Wentworth eyes on her. His feelings towards her are well documented in his letters.

“My love has made me selfish. I cannot exist without you. I am forgetful of everything but seeing you again. My life seems to stop there and proceed no further. You have absorb’d me. I have a sensation at the present moment as though I was dissolving. I would be exquisitely miserable without the hope of seeing you. I have been astonished that men could die martyrs for religion. I shudder at it, I shudder no more. I could be martyred for my religion, love is my religion, I could die for that – I could die for you.”

In another letter he wrote with some poignancy:

“I have two luxuries to brood over on my walks - your loveliness and the hour of my death.”

His love for Fanny is beyond doubt but whether they were reciprocated we can never know for all her letters to him were destroyed. With little money, no prospects and sustained by the kindness of friends’, marriage was in any case out of the question.

By now Keats health was deteriorating rapidly and, in the summer of 1820, it was suggested to him that he travel to Italy where the warmer climes would be better alleviate his condition. The situation echoed his verse:

Darkling I listen, and call for many a time,

I have been half in love with easeful death,

Call’d him soft names in many a mused rhyme,

To take into the air my quiet breath.

He left on 14 September but due to unforeseen circumstances the journey took longer than expected and he didn’t arrive in Rome until November when the weather was little better than it would have been in London. He soon became so ill that he was no longer able to write, and it was apparent to his friends that he had little time left.

He had been preparing for his death for much of his life and he met his end calmly and with resignation saying to those present at his bedside:

“Lift me up, I am dying. I shall die easy, don’t be frightened and thank God it has come.”

John Keats passed away on 23 February 1821. His pen quieted for evermore aged just 25, but the words he wrote remain eternal.

Ode to Autumn

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun;

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eaves run;

To bend with apples the mossed cottage-trees,

And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core;

To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells

With a sweet kernel; to set budding more,

And still more, later flowers for the bees,

Until they think warm days will never cease,

For Summer has o'er-brimmed their clammy cell.

Who hath not seen thee oft amid thy store?

Sometimes whoever seeks abroad may find

Thee sitting careless on a granary floor,

Thy hair soft-lifted by the winnowing wind;

Or on a half-reaped furrow sound asleep,

Drowsed with the fume of poppies, while thy hook

Spares the next swath and all its twined flowers;

And sometimes like a gleaner thou dost keep

Steady thy laden head across a brook;

Or by a cider-press, with patient look,

Thou watchest the last oozings, hours by hours.

Where are the songs of Spring? Ay, where are they?

Think not of them, thou hast thy music too,---

While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day,

And touch the stubble-plains with rosy hue;

Then in a wailful choir, the small gnats mourn

Among the river sallows, borne aloft

Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies;

And full-grown lambs loud bleat from hilly bourn;

Hedge-crickets sing; and now with treble soft

The redbreast whistles from a garden-croft,

And gathering swallows twitter in the skies.

John Keats, 1820

Share this post: