John Wilkes Booth: The Assassination of Tyrants

Posted on 18th January 2021

By the spring of 1865, the Confederate States of America were in abeyance and four years of bloody conflict at last appeared to be ending.

In the South William Tecumseh Sherman was making that cradle of secession South Carolina ‘howl’ as he had Georgia before it while the Confederate Army of Joseph E Johnstone merely stood aside seemingly incapable of doing anything to prevent it. In the North, Robert E Lee remained defiant in the trenches outside Petersburg grimly determined to defend the Confederate capital Richmond but in reduced circumstances with munitions low and reinforcements few eventual defeat,

seemed inevitable. In the meantime, the Union blockade of Southern ports had destroyed commerce with the shortages that resulted causing rampant inflation and rendering the Confederate currency all but worthless.

In Washington, President Abraham Lincoln had since won a second term of office determined to see the war through to its bitter end. The Confederacy, he knew, was being strangled out of existence. But one man at least refused to accept the inevitable, a man who had never been a soldier, never taken up arms in defence of his country and had not so much as fired a shot in anger, that man was - John Wilkes Booth.

Booth was a Southern nationalist and a firm believer in the institution of slavery never took pains to disguise either. He believed in the superiority of Southern manhood over their Yankee Northern counterparts and in the inferiority of the black races. Only independence for the South from the United States could protect Southern culture and society from being dragged into the pit of degradation that Yankee financiers and abolitionists would drag them.

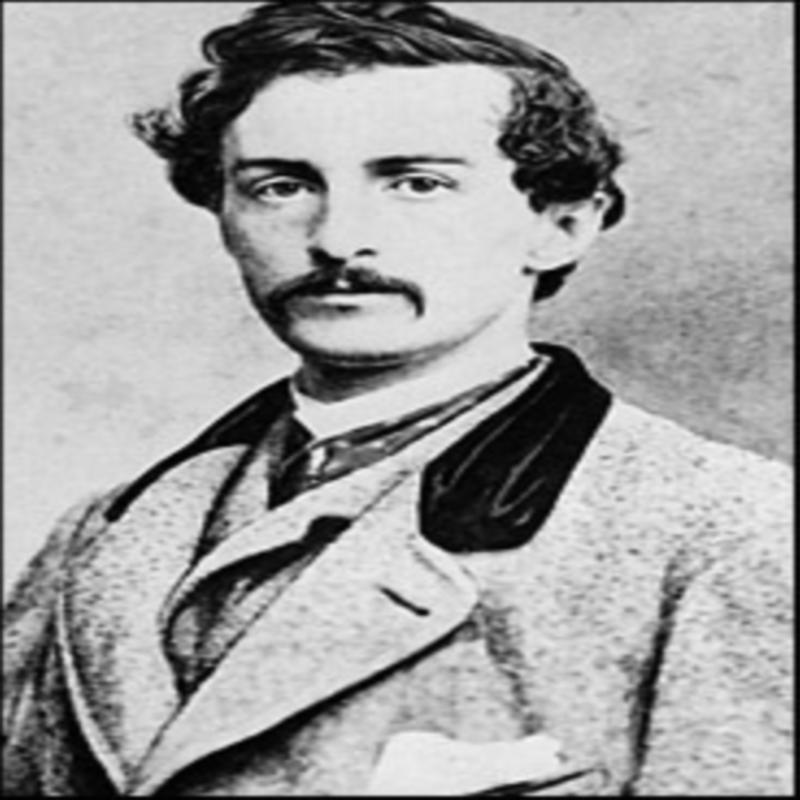

He had been born in Bel Air, Maryland, on 10 May 1838, the scion of a successful family of actors, and he was to follow in their footsteps. His childhood, though a happy one had not necessarily marked him out for success. He was a dreamer and somewhat of a romantic and his academic abilities did not impress so perhaps a career on the stage was inevitable.

Despite attending a Quaker school, he was raised an Episcopalian, a Church that had remained loyal to Britain during the American War for Independence and appeared to struggle with the concept of America as a unitary State. It imbued in him a sense of rebellion and otherness and he had become involved in secessionist and anti-immigration politics when he was still a boy. By the age of sixteen however, he had decided to follow his two older brothers into the theatre.

His stage career was a success and often joining with his brothers his interpretation of Shakespeare was well considered to the point where he was being referred to as one of the finest actors of his generation. He enjoyed both the accolades and the money.

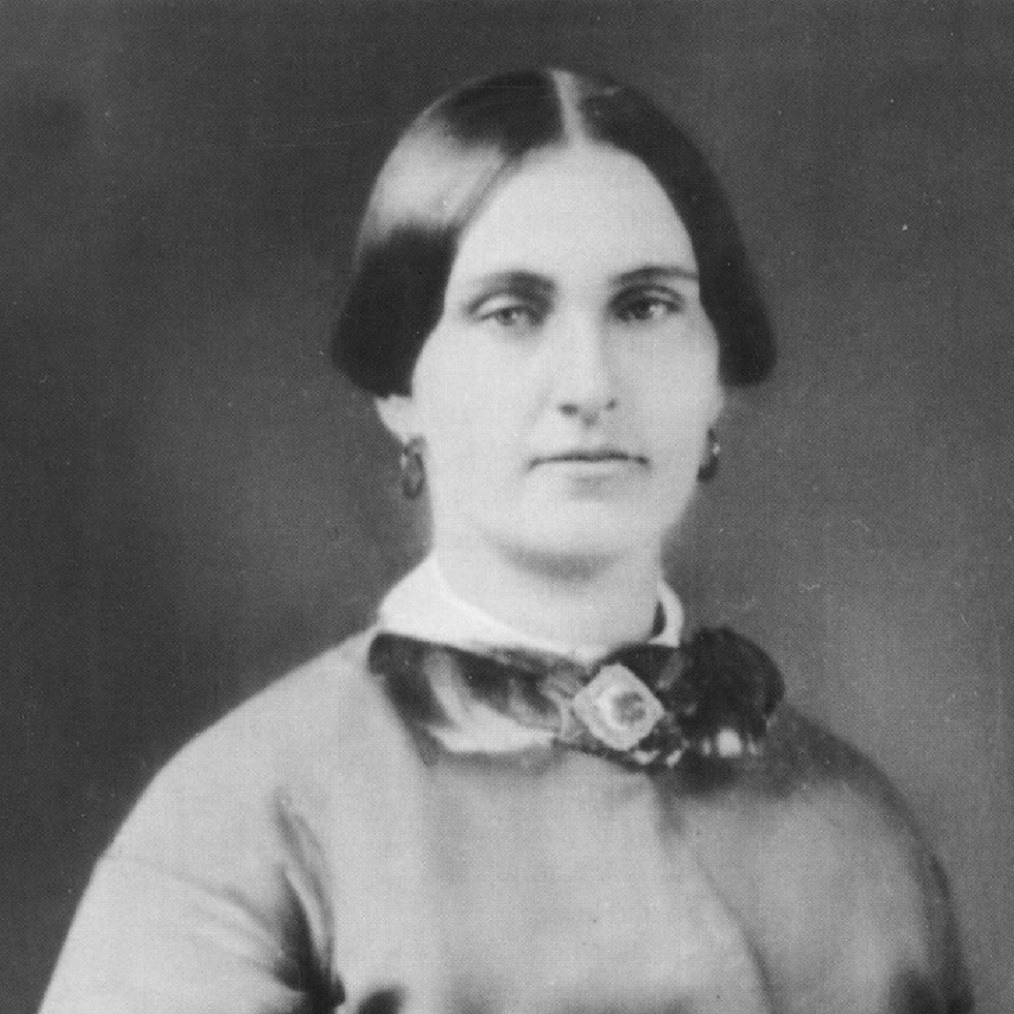

Mixing in the best circles in Washington Booth was considered one of the most handsome men in America. He was a celebrity and a darling of the ladies and it was not unknown for those of the more genteel class to carry his picture in their purses. By the late 1850's, Booth was earning $20,000 a year and life was good. He was soon to get engaged to his childhood sweetheart, but behind the veneer of a gilded life of wealth and fame he was a troubled man.

He remained committed to the cause of Southern independence, but he could never bring himself to fight for it. The nearest he ever got was when he borrowed the uniform of a member of the Virginia State Militia so that he could attend the execution of the abolitionist John Brown. Not long after the outbreak of hostilities between the States he left Virginia for Washington and returned to the stage.

By late 1864, it was becoming increasingly clear that the Confederacy was going to lose the war. The South had pinned their hopes on holding out long enough for the pro-peace candidate, General George Brinton McClellan to defeat Abraham Lincoln in the forthcoming Presidential election. When Lincoln won by a landslide the South was plunged into despair.

Booth, who had continued to entertain the good people of the North throughout the war and had become wealthy as a result, was disgusted with himself. He confided to his diary: "I have to deem myself a coward, and I despise my own existence."

In March 1865, he had witnessed Lincoln's Inauguration Speech and was standing so close to the President that he felt he could have touched him. He wrote in his diary: "I had an excellent chance to kill the President, if I had wished."

On 11 April, Abraham Lincoln gave a speech from the balcony of the White House in which he confirmed his intention to bestow voting rights to certain blacks. John Wilkes Booth, who was again in attendance, was overheard to remark: "Now by God! I'll put him through! That is the last speech he will ever make."

He was by now determined to kill Lincoln a man for whom his loathing knew no bounds. He had earlier raged at his sister, Asia: "That man's appearance, his pedigree, his low coarse jokes and anecdotes, his vulgar similes, and his policy are a disgrace to the office he holds. He is made the tool of the North to crush out slavery."

But his plot to kill Lincoln had originally been part of a wider conspiracy.

He had long been in contact with the Confederate Secret Service and in October 1864, travelled to Montreal in Canada to meet with their agents. Now he gathered together a group of fellow conspirators including David Herold, a pharmacists assistant and fellow native of Maryland, who had once worked for the Quack Doctor Francis Tumblety later identified as a suspect in the Jack the Ripper murders; George Atzerodt, a German immigrant who could barely speak English; Lewis Thornton Powell (who also went by the name Payne) a Confederate soldier who had been wounded and taken prisoner at the Battle of Gettysburg. He later escaped his incarceration and joined John Singleton Mosby's Partisan Rangers before returning north and agreeing to work for the Confederate Secret Service; John Harrison Surratt, a postmaster and Confederate spy; and 43-year-old Mary Surratt, John's mother, who ran a boarding house where the conspirators met and stored arms.

They were a disparate group united only by a desire to do something, anything, to further the cause they all believed in.

It had originally been intended to kidnap Lincoln and spirit him away to Richmond where he could be exchanged for thousands of Confederate prisoners-of-war. Plans were made to snatch him as he returned in his carriage from a trip to the theatre, but he decided not to ride out that day. The conspirators returned home disappointed.

It was becoming increasingly evident to everyone that the Confederacy was close to expiring as a coherent entity and so Booth’s plan to kidnap the President was abandoned in favour of more decisive action. Gathering the conspirators together Booth informed them that he would assassinate Lincoln. At the same time George Atzerodt would kill Vice-President Andrew Johnson and Lewis Powell would murder Secretary of State William H Seward.

On 2 April 1865, General Robert E Lee was forced to abandon his position around Petersburg following a Union breakthrough. The following day the capital Richmond fell. Nine days later the Army of Northern Virginia surrendered at Appomatox Court House. As news of these disasters filtered through to the conspirators in Washington they were imbued with a sense of urgency. If they were to strike at all they had to do so now.

Booth knew through his connections that the Lincoln's would be attending a production of the popular comedy My American Cousin at Ford's Theatre in Washington on the night of 14 April. He called the other conspirators together to tell them they would implement their plan that night.

Earlier that morning in a moment of prescience Abraham Lincoln had remarked to his bodyguard George H Crook: "Do you know, Crook, I believe there are men who want to take my life. And I have no doubt they will do it."

Booth had been drinking in the saloons and taverns of Washington throughout the evening and did not arrive at Ford's Theatre until around 10 pm. He immediately headed for the theatre's bar where he had a large brandy. While Booth continued to fortify himself with Dutch courage the President and his party, his wife Mary and a young Army Officer Henry Rathbone accompanied by his fiancé all seemed to be enjoying the play tremendously. There seemed little danger, so Lincoln had earlier permitted his bodyguard to leave his private box and watch the production from the stalls.

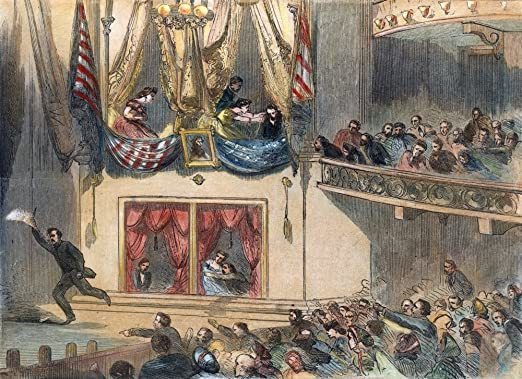

Booth, armed with a single shot derringer pistol and a hunting knife knew the play well and was aware of the line that would raise the biggest laugh. He was waiting for this moment to strike hoping that the noise from the audience would disguise the sound of the gunshot. He now waited anxiously outside the President's box.

As the crowd burst into laughter, Booth pulled back the curtain of the President's Box and shot him in the back of the head. As he did so Rathbone grabbed him and, in the ensuing, struggle the young Army Officer was stabbed repeatedly in the arm until he was forced to let go and Booth was able to break free. Leaping from the balcony onto the stage his spur got caught on the drapes and he fell awkwardly. Rising to his feet he cried "Sic Semper Tyrannis" (Thus, always to tyrants). He then fled the scene, hobbling away on his now broken ankle.

There was pandemonium in the theatre as it began to dawn on people what had occurred. Lincoln was treated by a young student doctor who had been in the audience but there was little he could do. Taken to a nearby house he died the following day having never regained consciousness. In the meantime, the other assassination attempts had failed.

George Atzerodt had arrived at the home of the Vice-President Andrew Johnson but had lost his nerve and too afraid to carry out his mission had fled in panic.

Lewis Powell however, had broken into the house of the Secretary of State William H Seward where he attacked him in his bed stabbing him repeatedly. When he was pulled off the terrified, cowering Seward by his bodyguards he shouted "I'm mad! I'm mad!" Seward though seriously wounded and scarred for life was to recover from his injuries.

Booth had arranged for a horse to be held for him outside the theatre by a young boy Joseph "Peanuts" Burroughs who had no idea that he was helping the man who had just assassinated the President.

Joined by David Herold, they both now fled Washington intending to make for Southern Maryland where Booth believed the sparsely populated, densely forested swampland would help facilitate their escape into rural Northern Virginia. But first they stopped off at the Boarding House of Mary Surratt to collect supplies and re-arm. They then made for the home of Dr Samuel Mudd, a known Southern sympathiser and sometime Confederate spy, where Booth could get his leg fixed. Dr Mudd patched him up as best he could, but they couldn't remain long.

On 16 April, they arrived at the house of Samuel Cox who told them to hide in nearby woods while he contacted the Confederate Spymaster for Southern Maryland, Thomas A Jones. He told them to remain where they were while he made arrangement for them to cross the Potomac River.

In hiding Booth insisted the newspapers be brought to him every day but expecting to be thought of as some kind of romantic hero he was shocked to discover himself excoriated and despised. Though there had been much rejoicing in the South at Lincoln's death there was even criticism from this quarter at what he had done. It had been pointless, they said. It could only heap even further misery upon an already a defeated nation and was the action of a madman.

To be criticised by those in whose service he believed he was acting hurt him deeply. He wrote in his journal: "With every man's hand against me I am in despair. And why, for doing what Brutus was honoured for. Yet I struck down a greater tyrant, and for that I am looked upon as a common cutthroat."

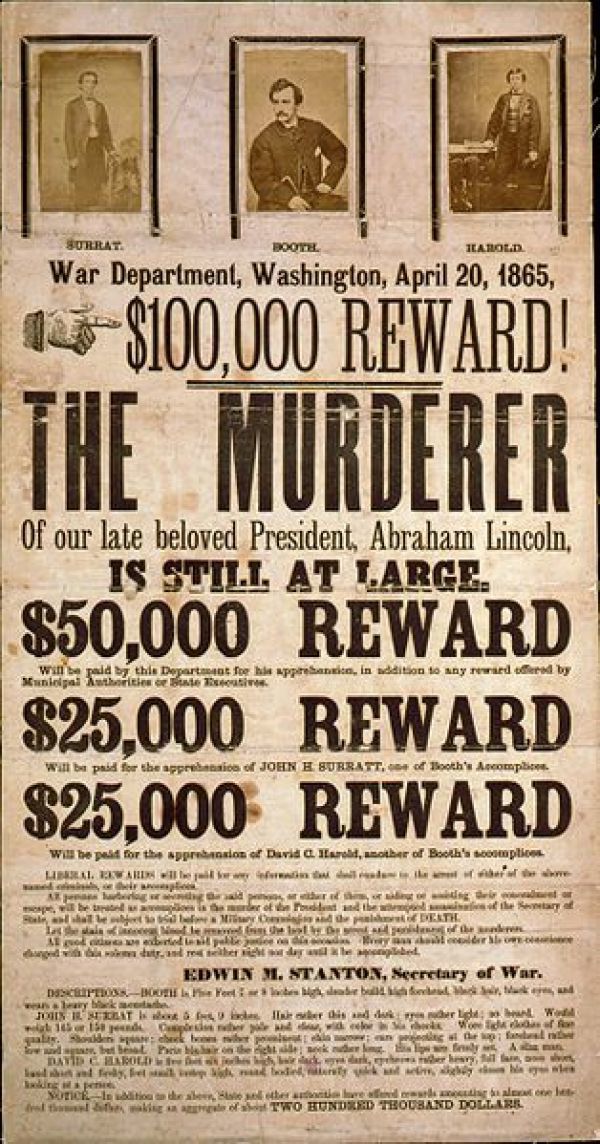

Continuing their flight south Booth and Herold were helped by a network of Southern agents that had been organised by Jones, but Federal forces were hot on their heels and Booth was aware that a $100,000 reward had been offered for information leading to his capture. This was a sum of such magnitude that he knew there was literally no one he could trust with any certainty.

Eventually the conspirators crossed the Potomac River and provided with fresh horses by Confederate Agent William S Bryant they reached Port Royal, Virginia. Booth was relieved to at last be on Southern soil. An ex-Confederate soldier William S Jett then led them to the farm of Richard H Garrett where it was thought they could hide until the opportunity arose for them to flee further south, possibly to Texas or even Mexico.

The collapse of the Confederacy meant that the mail was no longer being delivered and so Garrett was unaware that the President had been assassinated. He thought he was harbouring Confederate soldiers trying to evade capture.

On the night of 24 April while dining with the Garrett's, news reached the farm that Joseph E Johnstone had surrendered the Army of the Tennessee, the last remaining Confederate force of any significance still under arms. Booth fell silent at the news; the Garrett's were now also aware of the assassination and of the reward on offer. When Booth made mention of the size of the reward Garrett expressed the view that if he knew of the culprit’s whereabouts the reward would sorely test his loyalty. Booth remained impassive to these remarks and said nothing.

Unknown to Booth that same night a detachment of 26 troopers had been dispatched from Washington under the command of Lt Edward P Docherty to hunt for Booth and Herold following tip- offs that they had been seen hiding out in the swamps and woodlands of southern Maryland.

Following further information on 25 April they crossed the Potomac River into Virginia and headed for Port Royal. Hearing the troops approaching the Garrett Farm Booth and Herold fled to a barn but they were seen doing so and Lt Docherty ordered his troops to disperse and surround it. Booth was heard to shout "Who are you?" To which Docherty replied, "It doesn't matter who we are, we know who you are." Booth then asked the troops to stand back a bit, if they did so, he would emerge and shoot it out with them.

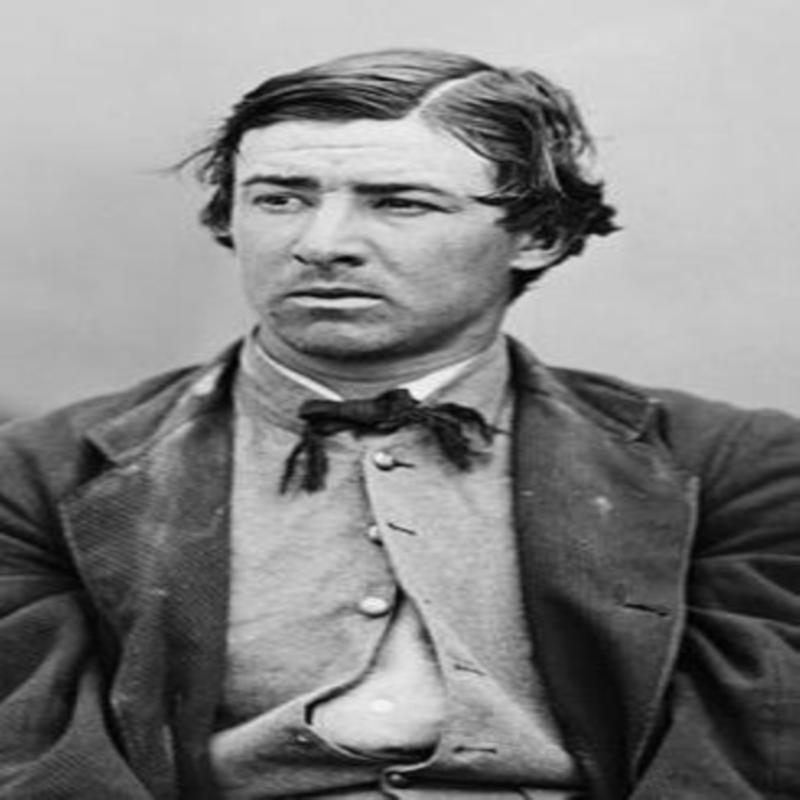

David Herold, who had no intention of shooting it out with anyone, could now be heard arguing with Booth who accused him of being a coward for deserting him. Herold soon after emerged from the barn with his hands in the air and was promptly tied to a tree. Booth would not surrender, however.

Docherty had wanted to take Booth alive and had ordered his troops not to open fire. It was now that Sergeant Thomas "Boston" Corbett intervened. He was an English immigrant and a religious crank who to prevent himself from sinning any further with prostitutes had sliced off his own genitals. He would later die in an Insane Asylum.

Seeing Booth through a crack in the barn wall Corbett ignored orders and shot him in the back. Booth collapsed to the ground his spinal cord broken. Taken to the Garrett's house he was laid out on the porch. Doctors were called but there was little they could do to keep him alive. There he lay for many hours in great pain. Aware that the end was near he whispered to one of his guards: "Tell my mother, I died for my country." Then holding his hands up to his face he cried "Useless! Useless!" They were the last words he ever spoke.

In a letter written to his sister Asia, that was to be opened only upon his death, he provided vindication for acting as he did. He spoke plainly of Southern rights and wrote:

"The institution of slavery is one of the greatest that God has ever bestowed upon a favoured nation . . . I love justice more than a country that has disowned it. I love it more than I do fame or wealth."

The assassin Booth may have been dead but the North's thirst for vengeance had not yet been quenched. It seemed that following the assassination anyone who had had the merest acquaintance with Booth and Herold were under suspicion and there were many arrests. Amongst those rounded up in the ensuing days were George Atzerodt, Lewis Powell, and Mary Surratt. In total eight people would stand trial for the assassination of President Lincoln. The trial however would not take place in the Civil Courts but before an especially selected Military Tribunal.

Michael O'Laughlen and Samuel Arnold, who been involved in the original plot to kidnap Lincoln were sentenced to life imprisonment. As also was Dr Samuel Mudd, who had only escaped a sentence of death by a vote of 5 to 4.

O'Laughlen was to die in prison but Arnold and Mudd were amnestied by President Johnson in 1869. Edmund Spangler who had procured the horse that Joseph Burroughs had held for Booth's escape was sentenced to 6 years imprisonment but was also released in 1869.

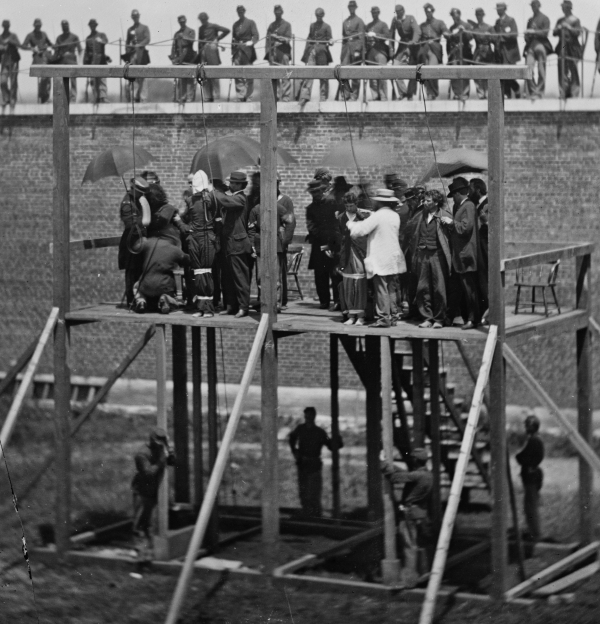

David Herold, George Atzerodt, Lewis Powell, and Mary Surratt were sentenced to hang.

Mary's son, John Surratt had earlier escaped to Quebec from where he had taken ship to England and was for a time to serve as a member of the Papal Guard in Rome before being forced to flee. He was finally arrested by U.S Agents in Egypt. Returned to America in 1867, he was to stand trial for his part in the plot, but the Statute of Limitations had run out on many of the charges he faced and he was released. He was not to die until 1916.

During their captivity the four condemned conspirators were treated harshly. Kept in close confinement in the intense heat on a boat moored on the Potomac River they were manacled, denied visitors, and made to wear a tight-fitting leather mask that stifled speech and restricted breathing.

Mary Surratt was to be the first woman executed by the United States Government. She had been sentenced to death not for being an active participant in the plot to assassinate the President but as a facilitator of it. As such, five of the jurors wrote to President Andrew Johnson requesting clemency for Mary and for her sentence to be commuted to life imprisonment. Johnson later claimed to have never received the letter.

The executions took place on 7 July 1865, at the Old Arsenal Penitentiary in Washington. It was a baking hot day, and a chair was placed on the scaffold for Mary Surratt. None of the condemned was permitted to address the crowd but their words would in any case have been drowned out by the jeers and chanting of the military personnel present. Mary Surratt requested that she not be hooded, but this was denied. At the specified time the trap doors were opened, and they were all hanged together, though it took some longer to die than it did others.

John Wilkes Booth's actions in assassinating President Lincoln had ended the best chance of a speedy reconciliation between former foes, and the South may have been treated harsher as a result.

Those who sought to asset strip the former Confederacy found their vindication for doing so in the assassination and were quick to raise the Bloody Red Flag at every opportunity and claim that the old Confederacy remained unrepentant rebels.

Southerners in response refused to accept the new reality and sought for many years to re-impose and safeguard what they believed to be the Southern way of life leading to segregation and the denial of equal rights to the recently liberated slaves and black population for the best part of another century.

But perhaps John Wilkes Booth's greatest legacy was by acting as he did a ‘great man’s’ reputation could never be tarnished; and that as a paragon of all the virtues Abraham Lincoln would be the guide to lead a country torn apart by war to reconciliation and eventual salvation.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous, War

Share this post: