Joseph Chamberlain and Tariff Reform

Posted on 24th March 2021

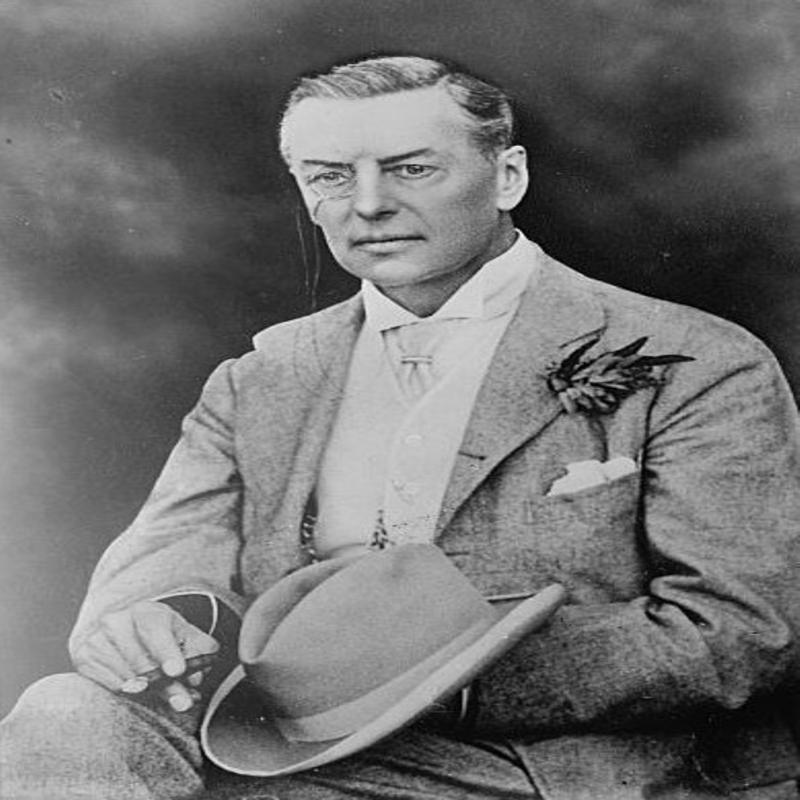

Born in London on 8 July 1836, Joseph Chamberlain was a self-made man who would rise from relative obscurity to become one of the most influential and divisive figures in late nineteenth century British politics.

The son of a shoe manufacturer his background was that of the sober middle-class, hard-working and with a sense of social responsibility so for the young Joseph there would be no sightseeing Grand Tour of Europe and no study beyond basic schooling. He was expected to earn his living and at the age of sixteen he began an apprenticeship as a Cordwainer, or worker in fine leathers.

Upon the completion of his training, he moved to Birmingham to work in his uncle Joseph Nettlefold’s small screw manufacturing company becoming a partner where under his astute stewardship it became the largest producer of screws in the country.

He soon became a very rich man as a result allowing him to concentrate on other matters – politics and the national interest.

Born into the liberal tradition prevalent among the manufacturing classes and the Unitarian Church in which he was raised his mantra was reform and the improvement of the living conditions of working people. Very much on the radical wing of the Liberal Party he wasn’t afraid to break ranks supporting Conservative proposals for electoral reform and the disestablishment of the Church in Ireland.

In Birmingham he formed an Education League that advocated the Government and Local Authorities take responsibility for educating the young removing it from the control of underfunded and by their nature non-inclusive Church Schools. In November 1873, he was elected Mayor of Birmingham promising that the city would be – parked, paved, marketed and gas and water protected. He was to prove as good as his word.

Arguably the most reforming Mayor in the country he could not of course eradicate poverty, but the slums would be cleared, the water made clean and the streets made safe. His achievements in Birmingham were widely praised so it was little surprise when in June 1876 he was elected unopposed as Member of Parliament for the city.

At Westminster his desire for reform remained firmly on the agenda but his impact on national politics would be very different.

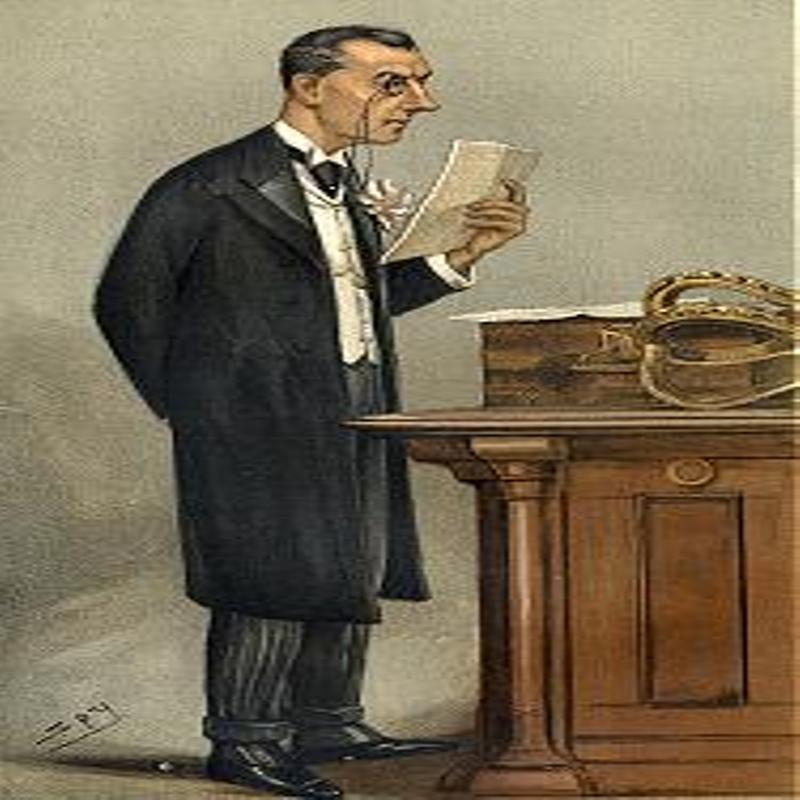

As a self-made millionaire who had not attended one of the great Universities, he had a certain disdain for the aristocratic political elite who had power thrust upon them though he wasn’t shy in adopting their style with his tailor-made suits, cigarette holder and trademark monocle; yet despite his common background and relatively late rise to national prominence he was to dominate the British political landscape for the next three decades. Indeed, he was to be as the young Winston Churchill described him – the man who made the weather.

Britain had been the first industrialised nation, the so-called Workshop of the World and a Free Trade country ever since the abolition of the Corn Laws in 1846. By the late nineteenth century, it possessed the greatest land Empire the world had ever seen even if it was said that it had been created from an absence of mind. If so, then Imperialism had since become very much a self-conscious doctrine and in the minds of most people Britain and its Empire were one and indivisible.

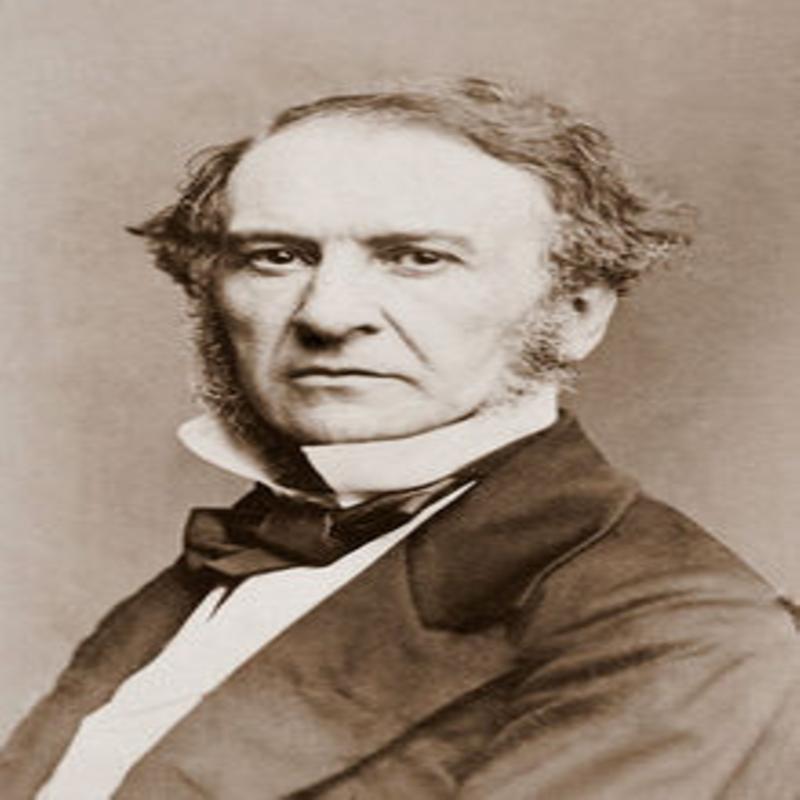

In April 1880, Benjamin Disraeli’s Conservative Government fell and in the resulting General Election the Liberal Party under Lord Hartington were swept to power. He was soon to stand aside as Prime Minister however, in favour of William Gladstone who in forming his Second Administration offered Chamberlain, the rising star of the Liberal Party, the post of President of the Board of Trade.

He was delighted to be offered a position in the Cabinet but was to find his time as a government minister deeply frustrating for unlike when he was Mayor of Birmingham he saw his many attempted reforms thwarted while at the same time becoming increasingly concerned with and distracted by the direction of British Imperial and foreign policy.

Gladstone, though his words did not always reflect his deeds, appeared to consider the Empire a burden, an attitude that greatly offended Chamberlain in particular his intention to negotiate with Charles Stuart Parnell, leader of the Irish Nationalists in Parliament a deal that would see Ireland granted Home Rule.

Gladstone’s proposed Home Rule Bill was to split the Liberal Party and at the forefront of the opposition to it was Joseph Chamberlain who was pivotal in the formation of the Liberal Unionists, effectively a party within a party. When on 8 June 1886, the Home Rule Bill came before the House of Commons and was defeated by 30 votes, 93 of those who had opposed its passage were Liberal Unionists.

When Gladstone lost the subsequent General Election, the Liberal Unionists split and formed a coalition with the Conservative Party that was to keep the Liberals from power for the next decade until it too fell as the result of a campaign organised and led by Joseph Chamberlain.

He was indeed making the political weather and his reputation and status was such that the Conservative Prime Minister Lord Salisbury offered him any role he wished within the new Administration but rather than accept one of the great Ministries of State he surprised everyone by choosing the relatively minor post of Colonial Secretary, but then for him the Empire had since become an obsession.

Britain in the 1890’s despite its pre-eminent position in the world was undergoing a crisis of confidence. She had already been outstripped in industrial output by the United States and Germany and would soon be involved in a naval arms race with the latter that appeared to threaten not only her dominance of the seas and her trade routes to the Colonies but the very existence of the Empire itself.

The British Empires vulnerability would be brought into sharp focus by the Boer War (1899-1902) which as Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain had been one of the primary architects. It had taken Britain and the might of her Colonies three years of bitter struggle to defeat 30,000 Boer farmers who they were forced into taking extreme measures to subdue.

The military humiliations endured were to be the cause of much mirth and mockery in the diplomatic drawing rooms of Europe while the brutality of Britain’s response provoked condemnation throughout the world.

British manhood it seemed had proven itself incapable of defending the Empire with many of those who had volunteered to do so being turned away from the recruitment centres as too emaciated, too deceased and too weak to fight. Only the white colonies rallying to Britain’s support had saved it from the prospect of defeat. It beggared the question, if the Empire could no longer be sustained militarily then other means would have to be found.

Concerns regarding the security of the Empire were not a recent phenomenon Its defence had been one of the guiding principles of British foreign policy for many decades, but some perceived in its implementation a lack of commitment and a sense of drift.

In 1884, the Imperial Federation League was formed by the future Liberal Party leader Lord Rosebery to establish closer ties with the Empire but a Federation by its very nature entailed political oversight which the largely self-governing white colonies of Australia, New Zealand, and Canada were unwilling to concede. Chamberlain likewise did not wish to diminish the authority of the white colonies who he saw as the bulwark of Empire and hoped would participate in the Empire’s continued expansion.

Chamberlain believed that closer economic ties with the Colonies would not only secure their future for many centuries to come but was the only way Britain would be able to compete with the rapidly expanding industrial capacity of Germany and the United States.

When Canada suggested the imposition of tariffs on its competitors to facilitate easier access to Imperial markets for its wheat in return for similar access for British manufactured goods Chamberlain was quick to seize on the opportunity declaring that - the time has come to abandon Free Trade.

When Chamberlain spoke, people listened and at a time of uncertainty and national self-doubt his proposals found a receptive audience with even the Cabinet at first appearing favourable to his ideas, though it was far from unanimous and was soon to change.

Many believed that Free Trade was the economic shibboleth upon which British commercial success was founded and saw in the multi-millionaire businessman Chamberlain’s protectionism only naked political ambition.

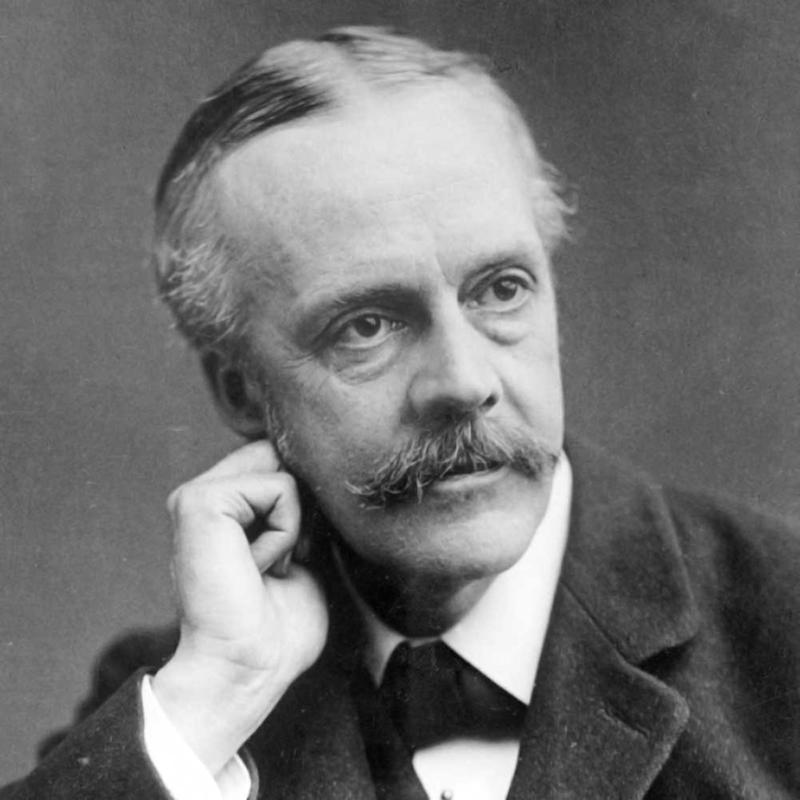

Amid increasing political those within the governing coalition divided over the issue and the Prime Minister Arthur Balfour, a diffident and effete man who did aloofness as only the British aristocracy could, was not the man to reconcile the irreconcilable.

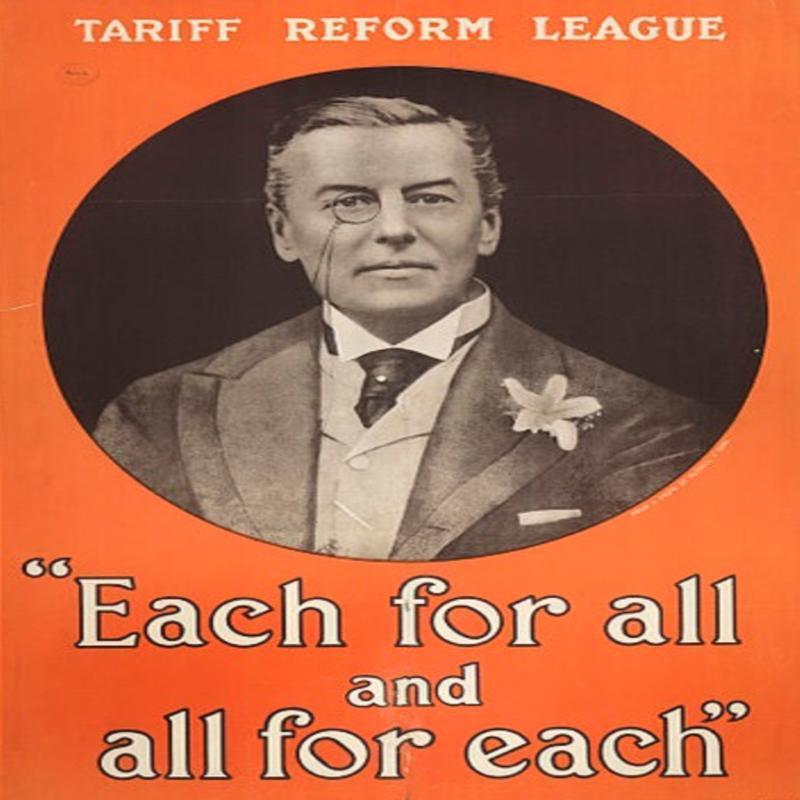

When it became evident that the Cabinet would not shift on the issue of Free Trade on 3 September 1903, Chamberlain resigned from the Government. Although he held no formal position within it, Joseph Chamberlain now became the spokesman for and public face of the recently formed Tariff Reform League.

Well-funded with many rich and influential backers the Tariff Reform League wanted to see Britain and its Empire become a single trading bloc insulated against competition by Imperial Preference that would see customs duties and tariffs imposed on competitors from outside.

Chamberlain now embarked upon a nationwide campaign for Tariff Reform explaining at a meeting in Glasgow how Free Trade damaged British industry: “Sugar is gone, silk is gone, iron is threatened, steel is threatened, and cotton will go. How long can we be expected to stand aside and take it?”

Chamberlain’s rallies were well attended and in some places, he was even mobbed and a certain triumphalism accompanied him but the rapturous reception he received was to prove in large part eye-candy for the gullible. In truth, his reputation as the reforming Mayor of Birmingham, the millionaire businessman who took heed of the needs of the people had faded into the past; he was now a national politician, a divisive figure increasingly conservative in outlook who had refused to compromise over Home Rule for Ireland, whose Imperial ambitions appeared limitless and who had to shoulder his share of responsibility for the fiasco of the Boer War. Popular as he was with the Tory grassroots his previous appeal amongst the working class was on the wane. But the dash, the charm, the oratory and the monocle remained, and he displayed considerable energy for a man in his late sixties. Wherever Chamberlain spoke he was followed closely by the Liberal Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer Herbert Henry Asquith who transformed the argument from one of Imperial Preference to higher food prices and the cost of living; as emphasis he contrasted the large metaphorical Free Trade loaf to a much smaller Protectionist one. It was an argument that resonated a people for whom the ‘Hungry Forties’ remained a vivid and very real collective memory.

Chamberlain responded to Asquith’s claims by having two loaves of bread baked of equal size which during his rallies he would hold up before the audience and ask them which is the larger?

He was trying to make light of an argument that he knew was true, readily believed and would not go away. The price of food would rise and all other factors - protection of the Empire, Britain’s position in the world and the prospect of social reform would be secondary to the money in people’s pockets and the food on their table.

Still, Joseph Chamberlain remained the most high-profile politician in Britain and for the next two years Tariff Reform would dominate the political agenda and the newspapers. But his campaign was damaging to both the Government and the Conservative Party in particular the latter which contained within its ranks many wedded to the notion of Free Trade especially among the business community. Under pressure from his own MP’s and party members Balfour declared he would hold a referendum on the issue, a promise he soon reneged upon, but the people would have their say, nonetheless.

Balfour’s indecisiveness (he had more than once indicated qualified support for Tariff Reform but now seemed in denial) contrasted sharply with Chamberlain’s brash and confident demeanour and his failure to heal the split within the Coalition made the continuation of his government untenable.

On 4 December 1905, he resigned as Prime Minister and called a General Election strangely confident of victory.

The election campaign was dominated by the issue of Tariff Reform with both sides able to muster support in the press, on the street corner and at the hustings making the outcome appear uncertain but the ballot box was to tell a different story.

The election result of 8 February 1906 saw the Free Trade Liberals swept to power in a landslide victory that reduced the Conservative Party from 302 to a rump of just 156 MP’s, the worst electoral calamity in its history with even its leader and now former Prime Minister Arthur Balfour losing his seat.

Even though the Conservative Party had not formally campaigned for Tariff Reform it had become so closely associated with the issue that in their defeat lay the seed of its rejection. But Joseph Chamberlain did not see it this way, he had increased his share of the vote and with Balfour no longer a sitting MP and the Conservative Party so denuded of credibility he became in the mind of the public at least the effective leader of the Parliamentary opposition.

It seemed that the election result though it may have tarnished his reputation had only served to strengthen his position and it appeared that his time was yet to come - but it wasn’t to be.

On 13 July 1906, less than a week after celebrating his seventieth birthday he was discovered by his wife collapsed on the bathroom floor, he’d suffered a massive stroke that would leave him partially paralysed. Over the following months and years, he would struggle to overcome his disabilities teaching himself to walk again but his speech remained slurred and his voice barely audible.

He would in time return to the House of Commons, but it would be quite literally as a silent backbencher unable any longer to influence events but only observe them.

With its most powerful advocate incapacitated the issue of Tariff Reform was hastily brushed aside as the Liberal Government with its radical Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George at the forefront adopted its own programme of social reform.

But fears over the future of the Empire and the impact of Free Trade on Britain’s economic prominence did not go away, it could still stir the passions and even as late as the outbreak of the Great War the Tariff Reform League could boast over 200,000 members.

Following his stroke Chamberlain’s health continued to decline and on 2 July 1914 he died of a heart attack. His passing was not just the end of an era but in the cauldron of World War he would be viewed almost as a man from a by-gone age.

Ironically, in the depths of economic depression the form of protectionism Joseph Chamberlain had long advocated would be implemented by his son and future Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain in the Ottawa Treaty of 1932, only to be abolished a decade later under pressure from the United States as part of the Lend-Lease Agreement during World War Two.

Share this post: