Kaiser Wilhelm II

Posted on 19th January 2021

Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert, a Hohenzollern, future and last Emperor of Germany was born on 27 January 1859 in Berlin at a time when the country he would come to rule made up as it was by a myriad of separate kingdoms, duchies, and principalities did not even exist other than as a geographical expression on the map of Europe; but he was destined to be King of Prussia nonetheless, Germany would come later after a long gestation and much like his own difficult birth with severe and lasting implications for the future.

His mother was the eighteen-year-old Princess Victoria known as Vicky, the strong-willed eldest daughter of Britain's Queen Victoria the future matriarch of Europe's many dynasties great and small.

She had been schooled by her father, Prince Albert, to think for herself and be unafraid to express her views. She also shared his liberal values, the English way of doing things, and was determined that others should believe in them to, among them her husband Friedrich, the Crown Prince of Prussia, but when he spoke in favour of greater press freedom or liberty of conscience it was not well received in a deeply conservative country little interested in reform and dominated by the army. It would in time see him increasingly alienated from his father and excluded from affairs of state. This came as a surprise to Vicky, from a country where a prince’s views on a whole range of issues were not just expected but sought, listened to, and even on occasion acted upon. But then the entire Prussian Court with its rigid protocol, cold palaces, and even colder servants was so unlike her cosy childhood in the bosom of a loving bourgeois family home. Even so, she would not be intimidated by the parade ground politics and barrack room manners of her new world. She would not be silent, she would have her say, and she remained determined that together she and the Crown Prince would change their country forever. Or so she thought.

But all such and their consequences thereof were as yet unknown, for now as a recently wed young princess she had her duty to perform, to provide the Prussian Monarchy with a son and future heir, and so it would be that on a cold winter’s afternoon in the Crown Prince’s Palace on the Unter den Linden in Berlin that a most protracted and painful labour began.

In attendance at her bedside was Queen Victoria’s personal physician Sir James Clark who was a great advocate for the benefits of chloroform which, despite finding the baby lying in the breech position, he had administered to Vicky in heavy doses to help deaden the pain and silence the screams which were frequent and loud. Indeed, so much had been absorbed she was almost comatose and incapable of helping in the delivery. Under such circumstances a Caesarean Section would normally have been contemplated but it was then a perilous procedure and after consulting with his German colleagues it was decided they could not risk the death of both mother and child. Instead, the baby was quite literally yanked from the womb with great force. In doing so, its left arm which was lying behind its back was crushed.

The injury was not apparent at the time and of far greater concern was the baby seeming not to breathe and it was only the timely intervention of one of the Princess’s female attendants who, much to the horror of the doctors present, took the baby and began to slap its face vigorously that likely saved the future Kaiser’s life.

The severity of the infant Wilhelm’s disability would become apparent over time and we can only speculate as to any brain damage that may have resulted from the violence of the delivery, though many would later remark upon his erratic behaviour and an evident emotional instability.

Vicky may have revelled in the joy of having given birth and glowed with good health but the same could not be said for her son who as a future King would require not just the moral strength to lead but physical accomplishments to be admired. As he grew into infancy it became apparent that his disability was graver than at first thought. She could not allow it to go untreated and determined that his paralysed and useless left arm would be cured a series of increasingly bizarre medical procedures were undertaken to that effect.

At the age of six he was subjected to a twice weekly ‘animal bath’ where his left arm would be placed inside the still warm carcass of a freshly slaughtered wild hare, it being thought that its hot blood and feral energy would transfer itself to his withered limb; he was also forced to undergo galvanism, or electro-therapy treatment, powerful electric shocks that were intended to jolt his arm back into life but the impact of such treatment was not on his disability but on his nerves with the possible psychological effects on a child made to endure the fear and pain of such a harsh remedy never even taken into consideration.

On other occasions his good arm would simply be tied behind his back forcing him to try and use his other arm which of course he was unable to do causing him great embarrassment and no little distress.

Vicky was observant of every aspect of her son’s well-being and by the age of four Willy’s tendency to tilt his head to the left was causing concern and so he was made to wear a brace that extended the length of his back and neck and was fixed over his head which when screwed tight kept it ramrod straight. This anomaly was at least overcome but there was little they could do about his arm, and it appeared his disability would be permanent. Vicky wrote in despair to her mother:

“The idea of him forever remaining a cripple appals me. It spoils all the pleasure and pride I should have in him.”

Vicky’s love for her first born diminished the more it became apparent he would remain an invalid and a distance grew between them. As a result, Willy’s childhood would be both a time of great affection and the most excruciating torment; a confused myriad of emotions that were reflected in a character that was needy, hyper-active, and prone to tantrums. Again, Vicky wrote to her mother expressing her concerns:

“He gets so fretful and cross and violent, and passionate he makes me quite nervous sometimes.”

Still, if she could not cure him then she could at least educate and mould him as a man. She would start by demanding that he learn to ride, withered arm or not, and learn to ride well. His disability should not be seen as an impediment and so he would learn to mount and dismount without assistance; to that end he would do so again and again and ride for hours without respite. If he lost his balance and began to fall, then he would be allowed to do so. If it hurt him then good, the sooner he would learn. When Friedrich watching his son and seeing him in tears complained to Vicky that she was too harsh, she replied – it must be done!

Vicky was also eager to inculcate her son with the same liberal values she had been taught at her father’s knee and so Willy was encouraged to play with the children of ‘common folk’ and even made to visit their homes. They were of course the children of respectable bourgeois, friends of the royal couple, but even so she was insistent that he learn of life outside the Imperial Palace and the confines of the Royal Court. All it achieved was to provide him with an inflated opinion of his own understanding, that no one knew the people better than he for he had spent time alongside them.

Wilhelm would come to view his mother’s teaching as weak and foolish and, in the end, reject them all,

At the age of eleven Willy was sent to Boarding School in Kassel and it was here that he first imbibed the Prussian nationalism that came to dominate his thinking.

Lonely and infused with that sense of abandonment many children feel when sent away from home his relationship with his mother was only intensified by her absence. The many letters he wrote (often not reciprocated) were affectionate and filled with longing. Vicky, when she did reply, was cold and unsympathetic - where he expressed his love, she corrected his grammar. Indeed, the letters exchanged between them bear stark testimony to the breakdown in their relationship.

The happiest periods of Willy’s childhood were spent with his grandmother at her home Osborne House on the Isle of Wight. It was here playing with his British cousins that he fell in love with the sea and later as Kaiser he would regularly attend the Cowes Yachting Regatta not as a tourist but as a competitor. He would race his own yacht determined to win, or at the very least finish ahead of his Uncle Bertie, the future King Edward VII.

On 18 January 1871 following Prussia’s victory in their short but bloody war against the French, in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles, King Wilhelm I was proclaimed Emperor of the newly unified Germany. Despite fears expressed in some quarters of Prussian domination a wave of patriotism swept the new nation as its people took pride in its achievement and Willy was no exception. He was thrilled by the turn of events and especially proud of his father’s role as Commander of the victorious Third Army. At odds though he often was with his father this fact alone would earn him his undying respect and in later life no little envy.

The genius behind German unification, however, was the Emperor’s Chief Minister Count Otto von Bismarck, a man who was to become increasingly influential in the young Wilhelm’s life and work to separate him from his father and the malign influence of the Crown Prince’s English wife.

With his coming of age Willy’s grandfather, the Emperor, decided it was time for the boy to become a man. He would learn the discipline the sense of duty, and experience the camaraderie that comes with army life and so he was commissioned First Lieutenant in the elite Foot Guards stationed at Potsdam. Here at last was a place he felt at home, somewhere he could be happy morning, noon, and night whether on manoeuvres, in the officer’s mess, or on the parade ground. The manly attributes of the soldierly life suited him down to the ground. If his disability was any impediment at all then no one cared to mention it – they were all stout fellows together. He wrote of his time there: “In the Guards I really found my family, my friends, my interests – everything I had up to that time had to do without.”

Despite his acceptance into the Guards as a fellow officer with few questions asked his disability did in truth remain problematic. He could not mount a horse without assistance or wield a sabre or lance once he had done so; he could only fire a rifle using his good arm and had to have it reloaded for him; even at dinner a footman would stand behind his chair ready to cut up his food, at least until a knife and fork mechanism was designed specifically for his use. He also walked with a limp and had done so ever since he’d had a tendon removed to help with his balance. But soldiers overcome such adversities, and so it was with the future Kaiser; he would become a competent if nervous rider, an expert marksman, and would stride out with confidence on the parade ground. He also learned to place the hand of his withered arm on the hilt of his sword making its paralysis barely visible even to those aware of it.

On 27 February 1881, Willy married his second cousin Augusta Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein known in family circles as ‘Dona.’ He had previously proposed to his first cousin Princess Elisabeth of Hesse-Darmstadt, the older sister of Alexandra the last Empress of Russia, but she had spurned his advances in favour of the Grand Duke Sergei. As a future King of Prussia and German Emperor he did not take kindly to being rejected for a Duke, Grand or otherwise, and certainly not a Russian one. It reminded him perhaps, of Germany’s parvenu status among the great dynasties of Europe, so it could be said he married Dona on the rebound much to the chagrin of his parents who considered her to be of minor nobility and unworthy of such elevation.

But if it was a hasty choice it was also a wise one for, she would prove the ideal partner for her rarely less than exuberant husband. She said little, remained in the background, had no opinions anyone was aware of, and bore him seven children in ten years without complaint - it was a happy marriage and by all accounts a faithful one.

While his successor once removed wallowed for the time being at least in domestic bliss the Emperor Wilhelm lurched towards a venerable old age retreating further and further from public life leaving both domestic and foreign policy in the capable hands of Bismarck, but even as he succumbed to physical infirmity and the increasingly maudlin reminiscences of a long life there would still be no political role for the Crown Prince. Instead the wily old Chancellor fostered a relationship with his son providing him access to government documents denied his father.

Willy soon forged an understanding with Bismarck, a man whose views appeared to correspond with his own. If indeed they were his own for Bismarck was a master at manipulation who had long sought to influence the successor to the Crown Prince, whose reign when it came would have to be hindered rather than helped.

So, for now the longer the old Emperor remained alive the better but he was drawing on borrowed time and on 9 March 1888, just thirteen days short of his 91st birthday, the account was finally closed.

The Crown Prince would be Emperor at last, and he could no longer be excluded from affairs of state. Here, after being side-lined for so long was Friedrich and Vicky’s opportunity to shape the future of Germany and forge it in their own image but he was ill, though few at the time realised how ill - what Friedrich believed was a lingering but heavy cold was in fact something far worse - throat cancer.

Vicky consulted the British cancer specialist Morrell Mackenzie who at first delivered a positive prognosis and recommended various treatments. Yet despite periods of apparent improvement and veiled optimism the decline in his health could not be reversed.

Willy was less than sympathetic and did little to lift the pall of gloom. Instead, he strode the corridors of power as if he were already Kaiser-in-waiting criticising his mother and loudly damning those who were tending to his father’s medical needs. Vicky wrote despairingly to her own mother in London: “Willy is saying it was an English doctor who crippled his arm and that now it is an English doctor who is killing his father.”

Despite being too weak to attend his father’s funeral the new Kaiser nonetheless remained determined to do what he could but by now unable to communicate verbally he ceased to hold meetings or attend royal functions. Vicky was distraught and became even more so when at the end of May he was confined to his bed. Informed by Dr Mackenzie that the cancer was malignant she insisted there must be an operation to remove the tumour but there was little they could do.

Friedrich wrote a last entry in his diary: “What is happening to me? I must get well again. I have so much to do.”

Emperor Friedrich III died on 15 July 1888 - his reign had lasted just 91 days.

Mourn though the country did over the death of its second ruler in just a few months Friedrich’s passing came as a relief to many in government circles, none more so than Bismarck who at least knew that his successor was no liberal. Indeed, he had guided the young Wilhelm in his political development to ensure this would be so and in doing so encouraged his estrangement from his parents.

He was to confirm his conservative credentials when in one of his first acts as Kaiser he ordered troops to surround the Royal Palace and have his mother’s private chambers ransacked in the search for court documents and proof of private correspondence she was sharing with her relatives in England. They found little evidence of Vicky’s alleged espionage, but it was to prove the straw that broke the camel’s back of their relationship. Unable any longer to influence his behaviour and aware that he resented her presence she went into a self-imposed exile on her country estate.

Wilhelm’s first public address as Kaiser was also not to his people but the army, and this concerned Bismarck. The prosperous and stable Europe with Germany at its centre was very much his creation but the peace was a fragile one and the balance of power built upon shifting sands. He knew that Germany was surrounded by enemies who bore the mask of friendship only out of fear and intimidation; to the West was a France still bristling with resentment over its loss of Alsace and Lorraine in 1871, in the East was an aggressive and expansionist Russia with its eyes on Constantinople and access to the Mediterranean; while Britain remained the dominant commercial power and would respond to any threat posed to its control of the seas and the protection of its trade routes to India and the rest of its Empire.

The political situation in Germany itself was no less precarious with its rapid industrialisation seeing the emergence of a working class and their representatives an increasingly powerful Socialist Party. Bismarck sought to curtail their influence by making concessions on welfare and pension rights while seeking to divide and rule in the Reichstag.

So, there was a delicate balance to be maintained in both domestic and foreign affairs and Bismarck was a master of both but the young Kaiser was not. He was just 29 years old, a young man with a short attention span, bombastic in his speech and impetuous in his decision making, who it was said lacked judgement - he hadn’t been expected to rule so soon and it showed.

The detail of politics and the everyday routine of governance bored him, and the popular image of him in some dress uniform or other entertaining friends and sipping champagne wasn’t an entirely false one. He was indeed more likely to be found in the company of his tailor or perusing the items on the wine list than he was at the cabinet table in the presence of his Ministers. But this didn’t prevent him from meddling in affairs of which he was at best ill-informed and at worst dangerously ignorant - a reckless foreign policy or ill-judged attempts at social reform could ruin everything. Bismarck tried to govern much as he had before, but he would no longer be given a free hand, and the Kaiser determined to assert his authority could rely upon the support of the Chancellor’s many enemies in Cabinet and at Court.

Wilhelm, who had previously admired Bismarck and even been in awe of him now found this single-minded, strong-willed, and stubborn old man an inconvenience. He would rule not reign and if his Chancellor interfered and tried to prevent him from doing so then he would have to go. It was in fact a dispute in the Reichstag over labour legislation (which the Kaiser supported, and Bismarck did not) which provided the excuse to wield the axe. When Bismarck refused to yield to the Kaiser’s way of thinking his resignation was demanded. It was duly received and accepted on 20 March 1890. Count Otto von Bismarck’s long and distinguished political career was over – the Iron Chancellor was no more.

Wilhelm did not require advice and in any case doubted the significance of diplomacy in foreign affairs; there were few difficulties on the world stage that could not be sorted out between Emperors and especially those who were close relations. He believed himself to be on good terms with his cousins both in Britain and Russia therefore, any problem could be resolved over dinner or via an exchange of telegrams and private letters.

Likewise, opponents in the Reichstag, or the Monkey House as he preferred to call it, might well squabble with his representatives but could always be assuaged by his words and would never fail to condescend in his presence - he was Kaiser, after all.

But he was not a figure as admired and respected around the world as he imagined. Neither was his authority ever quite what it seemed at home. The realisation of both these facts would come as a profound shock to a man not given to introspection.

It was true that he could manipulate his cousin Tsar Nicholas but then so could everyone else while his relationship with his British cousins was in fact often strained and his frequent visits to England not always welcome. Likewise, an invitation to visit him in Berlin was held in dread for he was never less than overbearing. But he could also be charming when the mood took him, and both offensive and sentimental in equal measure, at one moment berating perfidious Albion for her many misdeeds, the next waxing lyrical about the many happy days he spent at Osborne House and the love he felt for his English family. He could barely speak of his grandmother Queen Victoria without a tear in his eye, and to his mind it was only fitting that she had died in his one good arm. Not that she had intended to do so. It was instead the result of the doctor repositioning Her Majesty to make her more comfortable.

He was also a great admirer of his ‘Uncle Bertie,’ who succeeded to the throne in 1901 as King Edward VII, though he thought him as much a rival as a friend and was not averse to belittling him should the opportunity arise. Once at the Cowes Yachting Regatta when asked if he knew of the whereabouts of the Prince of Wales, who was in fact having lunch with the tea magnate and businessman Sir Thomas Lipton, he replied: “I believe he is dining with his grocer.” It was intended more as an insult than a joke. He wasn’t after all, a man known for his sense of humour unless it involved a bodily function, someone else’s misfortune, or a ritual debagging.

In truth he could be unbearable, Queen Victoria had long before described him as a petulant child and his constant craving for attention and rigidity of demeanour even at the most informal of occasions drove many to distraction. Even in a world where blood was thicker than water and it certainly was among the Royal Families of Europe, he was a difficult man to stomach. Yet he was proud of his British blood and envious of their customs and traditions, though he hated the Monarch’s purely ceremonial role; but he was also envious of its longevity, of the Empire it represented, and he would seek to challenge the authority of Britain at every turn, and in increasingly reckless ways.

Still, if Wilhelm was not beloved by a vast swathe of his relatives, he remained popular with his people who liked their assertive and vigorous Kaiser so firm of speech and strident of manner. They appreciated his love of display (few men enjoyed a parade more) and were emboldened by an army over which he took such pride and the powerful navy he had created – he made them feel good about themselves. Yet even with their ebullient and self-confident Kaiser in charge Germany without Bismarck was like a ship with a leaky boiler and no rudder, forging ahead, going around in circles, careering out of control, and getting nowhere – Kaiser Bill was to prove a poor Captain and certainly no navigator.

In foreign policy he threatened, and bullied, and provoked crises in Morocco (twice) and in Algiers that brought Europe to the brink of war. He nurtured a relationship with the Ottoman Empire that actively sought to promote anti-British sentiment in the Islamic world and boasted of building a Berlin to Baghdad Railway that would directly threaten Britain’s control of the Suez Canal. He also supported the Boers in their war against Britain and did so publicly by sending a telegram of congratulation to Paul Kruger, President of the Transvaal, and later provided them with arms and financial assistance.

In 1902, he embarked upon a naval arms race with Britain determined to create a Kriegsmarine that could compete with the Royal Navy both for control of the North Sea and across the world. Much to his surprise the Government in Britain accepted the challenge forcing him to abandon his ruinously expensive project eight years later still far behind in Dreadnoughts and other armoured vessels.

No one quite knew what this Kaiser was going to do next, where his interest might be drawn, or to whom he might pledge his own and Germany’s support. The uncertainty it caused in the corridors of power made it appear as if Europe was always on the cusp of another crisis. His often-ham-fisted attempt at alliance building first with Britain against France and Russia and then with France and Russia against Britain only made matters worse. Yet when the confrontation finally came it saw the great powers of Europe arraigned against Germany which could only call upon the support of a reluctant Italy that soon reneged on its obligations and a besieged Austro-Hungarian Empire desperate merely to survive it.

Unlamented though he undoubtedly was by those who’d had the temerity to oppose him the once all-powerful and all-knowing Bismarck was sorely missed. The ineptitude of those who had succeeded him as Chancellor and of the man who had appointed them would destroy all he had so meticulously created – from the other side of the veil he must have been turning in his grave. Shortly before his death in July 1898 he had remarked: “One day the Great European War will come out of some damned foolish thing in the Balkans.”

On 28 July 1914, a bucolic young Serb nationalist named Gavrilo Princip shot dead the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife Sophie, in the Bosnian capital of Sarajevo. It was yet another Habsburg tragedy and as such, barely merited front page news but its repercussions would soon become apparent.

In Britain, Irish Home Rule dominated the news cycle while France was once more mired in scandal. In Germany, as elsewhere, people were departing for their summer holidays and most of Europe was distracted in one way or another, but not Austria-Hungary and neither, monitoring events closely, was Russia.

The murder of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife was an outrage but not one deeply felt in the Habsburg Court, at least not on a personal level. The heir to the throne was not popular among those who worked for him, and the aged Emperor Franz Joseph disliked his nephew intensely, a man he considered a dangerous radical and had never forgiven for marrying Sophie Chotek, a commoner to his mind he thought little better than a serving wench. Their murder and Princip’s links to the Serbian secret society the ‘Black Hand’ did however provide the opportunity long sought by the Commander of the Austro-Hungarian Army Conrad von Hotzendorff to teach the upstart Serbia a lesson and send a harsh message to Slav nationalists throughout the Empire - but would the professed defenders of that very same Slav nationalism, Russia, stand aside? Given their humiliation when forced to back down over the Habsburg annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1908, it seemed unlikely.

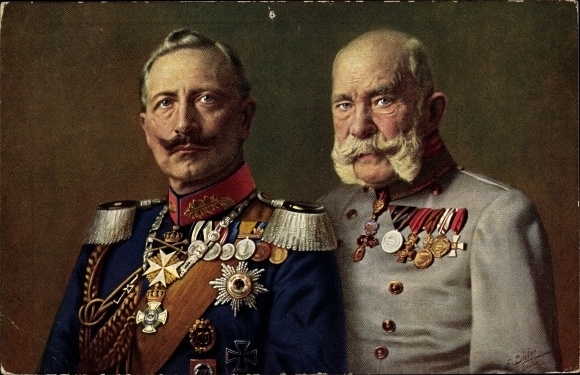

The threat of Russian intervention meant the Austrians dare not punish Serbia militarily unless they could depend upon German support and so it was that on 5 July, Count Alexander von Hoyos arrived at Potsdam from Vienna with two notes, one a formal representation to the German Government the other a personal letter to the Kaiser from the Emperor Franz Ferdinand, both requesting support for any action Austria might pursue in punishing Serbia the country they believed was behind the assassination of the heir to the throne and his wife.

The murder of one of their own never failed to send a shiver down the collective spine of the royal dynasts of Europe, and the murder of Franz Ferdinand was no different. He was also a close friend of the Kaiser’s which made it personal and given what we know of Wilhelm’s character his response then was not unexpected. He was bellicose and eager to help -the Emperor could rely upon his full support, he declared - but with the proviso that the Austrian’s march at once, there must be as little time as possible for the conflict to escalate. When soon after it became apparent, they were in no position to do so he began to demur – he would have to consult with his Chancellor and the Foreign Ministry, the army would have to be notified, plans put in place, he would say. But for now, that was not the case. On 6 July he wrote to his Austrian counterpart:

“The Emperor Franz Joseph may rest assured that His Majesty will faithfully stand by Austria-Hungary.”

It was the notorious ‘Blank Cheque’ and Count Hoyos was able to return to Vienna with it firmly in his pocket.

In the meantime, Wilhelm set off for his summer cruise of the Norwegian fjords oblivious to the path of destruction upon which he had inadvertently set the Continent of Europe.

The embers of war still barely flickered for much of that hot July imbued as it was with a sense of gaiety and ennui. But in the musty corridors of power from London to Paris and Berlin to St Petersburg increased diplomatic activity was stoking those very same embers and a frantic exchange of telegrams was ramping up the pressure.

Aboard his yacht the Hohenzollern, Wilhelm was becoming increasingly frustrated at Austrian inaction. Upon his return to Berlin, he curtly informed their Ambassador that had they acted sooner the looming crisis could have been avoided. His mood hardly improved when told that Austrian mobilisation had been paused while the harvest was gathered in.

The likelihood of a European conflict involving Germany in a two-front war had long been anticipated and planned for. Indeed, the strategy to be adopted in just such a scenario, with various revisions, had been in place since 1905. The Schlieffen Plan, so-named after its chief protagonist General Count Alfred von Schlieffen, called for the bulk of the German Army, some 1.5 million men, to advance into north-western France via neutral Belgium where, with its right-flank hugging the coastline, it would cut deep into the French countryside before turning east then north, encircling Paris from the rear and trapping the main French Army they felt sure would be attempting to seize back the lost territories of Alsace and Lorraine between itself and the German Army stationed on its western frontier.

The entire campaign in the west was planned to last just six weeks during which time Germany’s eastern frontier would be held by a mere 275,000 fighting men of the Tenth Army. It being assumed the sluggishness of Russian mobilisation would ensure there was little if any fighting to be done. Only with France defeated could the full might of German arms be turned upon its real enemy, Russia.

It was a bold plan, but feint heart never won fair maiden.

As for Britain, would she fight? Her defence of Belgian neutrality suggested she might. It remained a concern despite the Kaiser’s dismissal of her ‘contemptible little army.’ For her Navy certainly wasn’t contemptible neither was her Empire or the spirit of her people.

In the meantime, as the clouds of war loomed large and grew ever darker a series of increasingly desperate telegrams were exchanged between Willy and his cousin Nicky, the Russian Tsar, each begging the other not to take the fateful step to full mobilisation. But regardless of the fraternal greetings and words couched in the language of friendship neither could halt nor even slow the momentum towards catastrophe.

On 1 August 1914, Germany declared war on Russia. Two days later it would likewise declare war on France. But its demand that the Belgium Government surrender its sovereignty and allow the German Army to traverse its territory unmolested had been rejected. Even so, Britain had still not revealed its hand leading the Kaiser to rejoice - without British support the French would not fight there would be no two-front war:

“Now we need only wage war against Russia. So, we simply advance with the entire army East.”

But despite his demand for more champagne and that the attack upon France be halted his exultation would be brief. Informed that with the trains rolling west, Luxembourg already invaded, and troops massing on the Belgium border the Schlieffen Plan once implemented could not be stopped he shrugged his shoulders as if to say, then do as you will. He would later remark:

“To think that George and Nicky should have played me false, if my grandmother had been alive, she would ever have allowed it.”

On 3 August, from the balcony of the Imperial Palace in Berlin he addressed his people:

“This is a dark day and a dark hour. The crisis which is forced upon us is the result of an envy which for years has pursued Germany. The sword is being forced into my hand. This war will demand of us enormous sacrifice in lives and money, but we will show our foe what it means to provoke Germany.”

The following day he likewise addressed the Reichstag:

“I have no knowledge any longer of party or creed, I know only Germans, and in token thereof, I ask all of you to give me your hands.”

Attempts over the previous decade by socialists across Europe to unite and organise against war were now forgotten in the wave of patriotic fervour that swept the Continent. The Socialist Party, the largest in the Reichstag, the place the Kaiser had mockingly referred to as the Monkey House, now declared, “We shall not abandon the Fatherland in its hour of need,” and voted unanimously for the unprecedented War Budget of £265,000,000.

As he reviewed the troops parading through Berlin on their way to their way to the front Wilhelm told them, “You will be home before the leaves fall from the trees.” It was to prove a popular refrain in all the combatant countries. They would be home before Christmas – it wasn’t to be.

It appeared for time as if the Schlieffen Plan might work as the Belgian forts that hindered the advance were swiftly turned to rubble by artillery pieces of immense power borrowed from Austria-Hungary catching the French unawares and forcing the British into hasty retreat; but moving so many troops in such a narrow corridor was to prove a logistical nightmare for the Germans and making rapid reinforcement proved almost impossible. When in September near the River Marne the arc of the advance was changed so the attack broke down. The war of movement on the Western Front was over as both sides now dug-in and a line of trenches soon stretched from the Swiss frontier to the French coast.

The Kaiser who had so often rattled the sabre was unnerved by what he had unleashed but now having unsheathed the sword he would have to use it and he would prove no Frederick the Great.

There was to be no swift victory as there had been in 1870 and the longer the war continued the less interested in its detail the Kaiser became; he would attend military briefings, peruse the maps, and make suggestions but the war would increasingly be run by others most notably Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and General Erich von Ludendorff.

Only in naval affairs did he continue to assert himself rejoicing in ‘German Victory’ at the Battle of Jutland - the legend of Nelson at Trafalgar had been surpassed, he declared – but his mighty navy would remain bottled up in port for most of the remainder of the war and do nothing to break the blockade that was strangling Germany and starving his people.

He rarely visited the front and when he did the cameras were always present. In one such publicised event he was seen surveying the battlefield of Verdun from a safe distance through an armoured viewfinder. He declined to visit the wounded preferring the company of his Generals to that of the men they led, not that he was wholly unsympathetic to the hardships endured by the troops at the front he just didn’t know what they were. Likewise, as his people starved so the champagne continued to flow at Headquarters and the Royal Palaces of the Kaiser Reich.

But while the war stagnated in the West it developed a momentum towards inevitable German victory in the East that could not be prevented by Russia’s large, ponderous, poorly trained, under-equipped and badly led army. By the time the punitive peace of Brest-Litovsk was signed the Bolsheviks were in charge in Russia and his cousin Nicky and his family were their prisoners.

Wilhelm was sympathetic to his cousin’s plight and his wife urged him to do something, perhaps make the safe delivery of the Romanov family and their relatives into German hands part of any peace settlement. But the proposal of asylum gained little traction, and how could it, Russia had only recently been the enemy in a war that had cost a great many German lives. In any case, peace overtures had been rejected not once but many times, so why now should Germany be gracious in victory? Whatever the Kaiser’s personal feelings, nothing would be done. When in July 1918, he received the news that Tsar Nicholas, his wife, and their children had been murdered tears were shed but not by Wilhelm – Nicky was weak, if he had taken his advice, it would never have happened – but by Dona, her ladies, and others who had known the family personally. The lesson of their murder was also not entirely lost on the recipients of such bad tidings.

The conclusion of the war in the East freed more than 600,000 men for the Western Front giving the Germans a numerical superiority for the first time since the opening weeks of the conflict but it could only be temporary. General Ludendorff told the Kaiser the army must strike, that the British must be defeated before the American Army then gathering in northern France could become fully operational - it would be the last great German offensive of the war.

Operation Michael, or the Kaiser’s Battle, began on 21 March 1918, and it seemed for a time that the breakthrough had at last been made as the first line of trenches fell, then the second line, a significant breach had been made in the defences and tens of thousands of troops were killed and captured. By the end of the third day of the offensive the British Fifth Army was in full retreat. It was the deepest penetration on the Western Front since the summer of 1914.

His interest in the war reinvigorated on 23 March Kaiser Wilhelm pronounced: “The battle is won the English have been utterly defeated.”

He declared a public holiday and that church bells be rung the length and breadth of the country.

But Ludendorff’s master plan for victory lacked a strategic objective; did he seek to capture the railway terminus at Amiens the pivot of the Allied line, did he wish to capture Paris, or did he want to threaten the Channel Ports and force the British to withdraw to the coast? As a result, a desperate situation for the Allies was squandered as he switched the direction of the attack to wherever a breakthrough appeared imminent. By July, exhausted and having lost a quarter of a million men the German attack began to lose momentum and peter out. On 8 August, the Allies counter attacked. The German Army remained a formidable foe and some of the hardest fighting was to be witnessed in those final months of the war. Even so, they were surrendering in unprecedented numbers, desertion had reached dangerous levels, and Germany’s cities were crammed full of soldiers absent without leave.

On 8 August, during the Battle of Amiens 16,000 German soldiers were taken with barely a shot being fired. Ludendorff referred to it as the ‘Black Day of the German Army.’ By September it was clear that Germany had lost the war, Hindenburg knew it, Ludendorff knew it, only the Kaiser it appeared did not, but even he felt compelled to remark: “The troops continue to retreat. I have lost all confidence in them.”

Fearing the army was on the verge of collapse on 29 September, Ludendorff informed the Kaiser that they must seek an immediate armistice. Wilhelm agreed but he wanted an assurance that any approach to the Allies would not entail surrender. It was not an assurance he could give in good faith, but the General did so anyway. Well might the Kaiser remark, “the war has ended quite differently, indeed, from how we expected.” Not that he would take any responsibility, “the politicians have let us down miserably,” he said.

Despite Ludendorff’s worst fears the German Army continued to fight hard on the Western Front but at home where military discipline did not apply the situation was dire; famine conditions existed in many cities, anti-war sentiment was widespread, and the disorder that resulted increasingly unmanageable with street protests, food riots, and strikes becoming a daily occurrence – political radicals it seemed were everywhere, the plague of Bolshevism was spreading.

At his headquarters in Spa, Belgium, the Kaiser seemed oblivious to the seriousness of the situation. He still dreamed of leading his army to Berlin in person and restoring order by force. When he was verbally abused by troops on their way to the front who shouted that he was a murderer and butcher he was genuinely shocked – these were not his soldiers, these were not his guards! On 28 October, the German High Seas Fleet received orders to put to sea and break the British blockade in what was widely seen as a suicide mission. The order was ignored and so repeated a further four times. Still the crews refused to budge instead threatening violence, imprisoning their officers and establishing shipboard soviets.

Wilhelm was dismayed to learn that his beloved navy had mutinied, their unwillingness to fight he found incomprehensible, he put it down to the ‘Reds.’

Informed that he no longer had the confidence of the army, that they would follow Field Marshal von Hindenburg but no longer the Kaiser, he refused to believe it. When told that the Allies would not negotiate a settlement while he remained on the throne and that order could only be restored in Germany if he abdicated, he demurred. Could he not abdicate as Emperor but remain King of Prussia? The answer was no, the constitution did not allow for it - still, he refused to sign any abdication document.

On 9 November, his Chancellor, Prince Max of Baden announced the Kaiser’s abdication without even informing him of it. He then resigned from his post later the same day.

Wilhelm was furious with his nephew Prince Max but there was little he could do, and time was short if he wished to evade capture and so on 10 November he boarded a train bound for the Netherlands. Fearing it might be stopped by the radicalised troops of his once loyal army and that he might suffer the same fate as the Tsar, and Nicky was very much on his mind, the train was soon abandoned, and the journey completed by car.

The Kaiser’s presence in their country wasn’t entirely welcomed by the Dutch Government and Wilhelm worried with good reason that they might bow to international pressure and hand him over to the victorious Allied powers - and for a time that pressure was intense - in Britain his cousin King George V had already referred to him as ‘the greatest criminal in history’ and the Prime Minister David Lloyd George had recently won re-election on the slogan ‘Hang the Kaiser.’ While in France their Premier, Clemenceau, for whom everything was personal, thirsted for revenge. His prosecution was even called for in the Versailles Treaty but in the end wiser counsel would prevail particularly that of the United States President Woodrow Wilson who saw no benefit in pursuing the vanquished Kaiser.

The Dutch eager to maintain their position of neutrality, especially in the event of any future European war, were unlikely to extradite him an any case but neither would they allow his presence to embarrass them. He would remain under surveillance and require permission to travel.

On 9 November, his Chancellor, Prince Max of Baden announced the Kaiser’s abdication without even informing him of it. He then resigned from his post later the same day.

Wilhelm was furious with his nephew Prince Max but there was little he could do and time was short if he wished to evade capture and so on 10 November he boarded a train bound for the Netherlands. Fearing it might be stopped by the radicalised troops of his once loyal army and that he might suffer the same fate as the Tsar, and Nicky was very much on his mind, the train was soon abandoned and the journey completed by car.

The Kaiser’s presence in their country wasn’t entirely welcomed by the Dutch Government and Wilhelm worried with good reason that they might bow to international pressure and hand him over to the victorious Allied powers - and for a time that pressure was intense - in Britain his cousin King George V had already referred to him as ‘the greatest criminal in history’ and the Prime Minister David Lloyd George had recently won re-election on the slogan ‘Hang the Kaiser.’ While in France their Premier, Clemenceau, for whom everything was personal, thirsted for revenge. His prosecution was even called for in the Versailles Treaty but in the end wiser counsel would prevail particularly that of the United States President Woodrow Wilson who saw no benefit in pursuing the vanquished Kaiser.

The Dutch eager to maintain their position of neutrality, especially in the event of any future European war, were unlikely to extradite him an any case but neither would they allow his presence to embarrass them. He would remain under surveillance and require permission to travel.

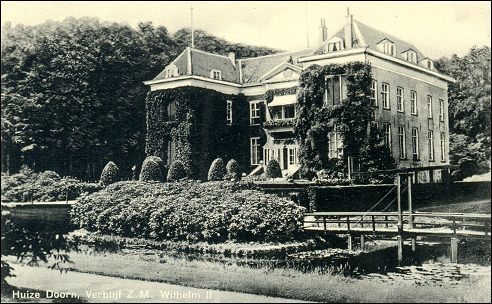

In May 1920, he moved into what would become known as the Doorn House, a country estate situated in the safety of the central Netherlands where he could live free from the fear of abduction. It would be his home for the remainder of his life and it was from here as a celebrity from a bygone era that he would hold court with, aside from those who merely came to gawp at the ex-Kaiser, eminent citizens from across Europe and elsewhere who visited to pay their respects. But it was tragedy that was to mark the early months of his exile.

On 18 July 1920, his youngest son Joachim committed suicide while less than a year later Dona, his wife of 40 years died. Wilhelm was devastated struggling to understand the former and greatly mourning the latter. Yet he was not one to let the grass grow under his feet and on 5 November 1922, he married Princess Hermine Reuss, a young woman who had become a frequent visitor to Doorn House and had long ago caught his eye.

Unlike the Kaiser who appeared willing to accept his life in exile Hermine remained ambitious for her husband and was determined that he should be restored to the throne, if not as German Emperor, then certainly as King of Prussia even if the role was to be a purely ceremonial one. There was little prospect of either as long as the Socialists remained in power, but an opportunity appeared to present itself when in January 1933, Adolf Hitler assumed the Chancellorship and Hermann Goering became one of the many prominent Nazis who were to pay homage at the Court of the ex-Kaiser.

Hitler may have fought for the Kaiser, but it seemed doubtful that he would be willing to share power with him even if it were more show than substance. Even so, talks continued for a time.

Any thoughts of a restoration were soon dismissed as illusory however, much to the relief of Wilhelm no doubt, who had no desire to wear a paper crown. Instead, he would remain at Doorn to work on his memoirs, enjoy the hunting, chop down the trees, drink champagne, and pontificate at length over dinner on why and where it all went wrong and what might have been - to his mind the fault lay with the Jews. As early as 2 August 1919, in a letter to General August von Mackensen he had written:

“The deepest, most disgusting shame ever perpetrated by a people in history the Germans have done unto themselves. Egged on and misled by the tribe of Judah, whom they hated, whom were guests among them! That was their thanks! Let no German ever forget this, nor rest until these parasites have been destroyed and exterminated from German soil, this poisonous mushroom on the German oak tree.”

He later told his doctor:

“The English, French, and German Jews were all in cahoots with one another. Their sole aim was to establish the Jewish domination of the world. Therefore, they first had to enslave the German people completely.”

Such anti-Semitic rhetoric was to become a regular refrain throughout his exile yet in the immediate aftermath of Kristallnacht, the Nazi pogrom of November 1938, he was to say:

“For the first time in my life, I am ashamed to be a German.”

His relationship with the Nazi Regime would always be a fractious one. In private he considered them an abomination to German culture, but he was careful not to rile them even if his praise for the Fuhrer was often sparse and rarely unconditional. When Nazi Germany achieved in just six weeks what the Kaiser had failed to do in four years of bitter conflict and force France’s capitulation, he sent Hitler a congratulatory telegram. It was perhaps, more significant for what it didn’t say:

“Under the deeply moving impression of Frances capitulation I congratulate you and all the German Armed Forces on the God-given prodigious victory with the words of Kaiser Wilhelm the Great of the year 1870. “What a turn of events through God’s dispensation.” All German hearts are filled with the chorale of Leuthen which the soldiers of the Great King sang in 1757. Now thank we all, our God!”

What Hitler made of that exactly remains unknown, but he was to express on more than one occasion that he thought the Kaiser mad.

Following their occupation of the Netherlands the Nazis for the most let the Kaiser be, though Dutch police at the gates of Doorn were replaced with SS Guards and he was once again placed under close surveillance. People who sought to visit him now required permission and those who continued to venerate him did so in private.

Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert, Wilhelm II King of Prussia and last German Emperor died of a blood clot on the lungs on 4 June 1941, aged 82. The Kaiser Reich he had ruled over lasted 47 years the Thousand Year Reich that replaced it survived barely 11.

The question remains however, was the Kaiser to blame for the war? Perhaps, if any one man could be blamed but there were many factors that contributed to the tragedy which ensued. – Austro-Hungarian belligerence, Russian intransigence, a complex series of treaties and alliances, pre-determined military planning, even railway timetables. Yet it cannot be denied that brinkmanship had been the hallmark of Wilhelm’s foreign policy almost since the time of his succession, that it was a dangerous game, and not one he played well. There is little doubt that the Blank Cheque he issued to the Austrian Imperial Representative on that fateful day in July 1914 was pivotal in leading the Great Powers of Europe into a war the magnitude of which was unforeseen and ill-prepared for. If any blame attached itself to him then he chose not to see it and certainly not to apologise for it. Even so, any prosecution of the Kaiser could only have been viewed as victor’s justice, a vindication almost of the persecution he believed had been his to endure since childhood. Better perhaps, a long and uneventful exile as a man from an age long past and committed to memory lost in the swirl of history and cast into the wilderness of irrelevance.

.

Tagged as: Modern

Share this post: