KKK: Rise and Fall of the Invisible Empire

Posted on 24th September 2021

The Ku Klux Klan was the offspring of war, more to the point it was the offspring of defeat in war.

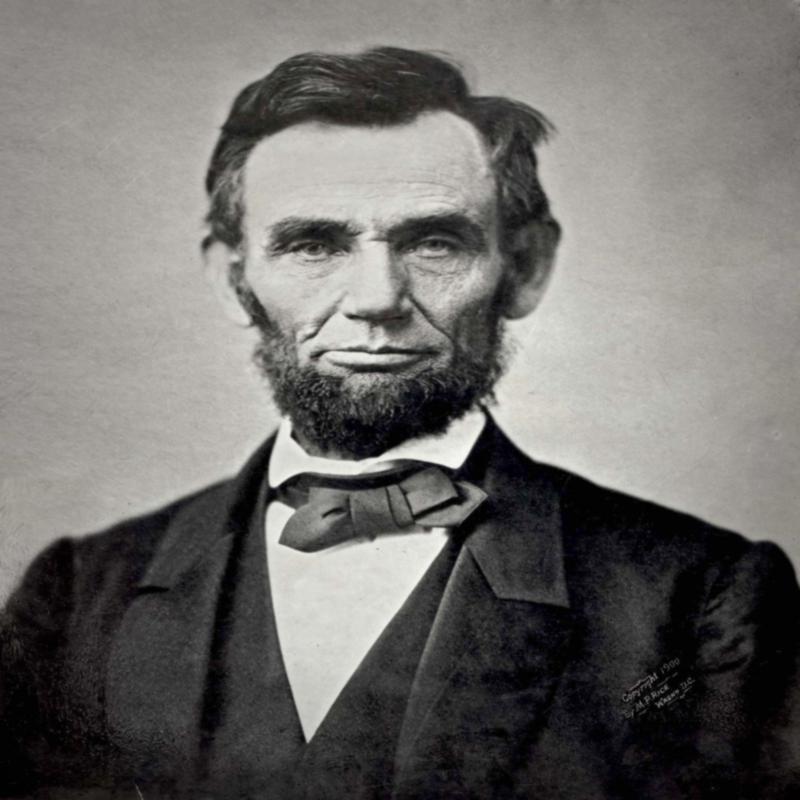

By April 1861, eleven Southern States in America had banded together to form a Confederacy and break away from a Union they saw as threatening their way of life. The recently elected President of the United States Abraham Lincoln who had been so unpopular that he had not even appeared on the ballot paper of most Southern States and whose effigy had been burned on the streets of Southern towns, had talked peace but prepared for war.

Under no circumstances was he willing to even contemplate the break-up of the Union and if it was to come to a force of arms then so be it.

The one issue that divided people more than any other and had done so ever since the founding of the country was slavery and if it was not alone the cause of the war it seems likely that without slavery in place no war would ever have been fought. It was the point of separation upon which there could be no reconciliation.

On 4 February 1861, the States of South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas formally seceded from the Union. They were to be followed soon after by Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina.

Abraham Lincoln, who considered himself a moderate was an anti-slavery man, but he had never called for its abolition merely its curtailment - there should be no new Slave States, he insisted. But to take the centre ground in an argument of such extremes only antagonises both sides. So, he could never truly be a hero of the Anti-Slavery Movement who demanded its complete abolition while as President his stance ensured he became an enemy of the South. By the time he took Office on March 4, 1861, the rush to secession was already underway.

The dividing lines had been so clearly drawn that there was little attempt at negotiation and despite Lincoln’s pleas for common sense to prevail in the early hours of 12 April Confederate batteries fired upon the Federal Armoury at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbour.

The Civil war had begun.

After four years of violent struggle which modern estimates now suggest as many as 720,000 Americans were killed by their fellow Americans the South was forced to concede defeat.

During the war much of the South had been laid waste particularly the States of Georgia and South Carolina, the beating heart of the secessionist movement.

There was a great deal of bitterness on both sides of the conflict but particularly in the Deep South where States such as Georgia and South Carolina, the beating heart of secessionism, had been laid waste during the conflict, punished for wanting to maintain the social order and preserving their way of life. So many young men they had sacrificed in a struggle against overwhelming odds in what soon became known as – the Lost Cause.

The victorious North thought, otherwise, the Secessionist South had no honour, they had committed an act of treason to maintain an evil and stripped of the moderating influence of Abraham Lincoln who had been assassinated in April 1865, the Congress in Washington was determined to punish those States that had embarked upon the course of rebellion. It seemed that at every possible opportunity Radical Republicans in Congress would unfurl the “Bloody Red Shirt” and blame the South for all the Nation’s woes.

In 1866, the States of the old Confederacy were divided into five Military Districts governed by a General supported by Federal troops, many of them black - the South was effectively under occupation.

In their wake followed a hybrid band of crooks, charlatans, and asset strippers known collectively as Carpetbaggers. Fallow Southern land, abandoned farms, and disused factories were bought on the cheap by Northern entrepreneurs and in a population of only 9 million there were 4 million recently freed slaves with no love for their former white masters in need of employment.

In March 1865, the Congress in Washington had established the Freeman’s Bureau. It had been designed to provide help to the many recently freed slaves and it built schools and hospitals but the various attempts to extend its powers were vetoed by Andrew Johnson, who had succeeded Lincoln as President.

The Fourteenth Amendment (and the 1870 Fifteenth Amendment) to the Constitution granted black men the right to vote in elections and those States that had previously been in rebellion could only gain formal re-admission into the Union by implementing the new male suffrage laws. But it was never that simple and the response in many Southern States was to introduce the Black Codes and Jim Crowe Segregation Laws which required any black man who registered to vote to be able to sign his own name, read from a book, or answer a long list of questions that he could not possibly know the answer to. Not being able to do any of these things would disqualify him from the registration process. Black men could also be excluded from sitting on a jury or testifying against a white man in court on the same grounds.

President Johnson vetoed any attempts to curtail the implementation of the Black Codes. He did not want to be seen to be punishing the South and was opposed to the Radical Republicans attempts to apportion blame for starting the Civil War, and likewise their demands that the South should be made to pay for doing so. He believed that his attempts at reconciliation as he saw it were what Abraham Lincoln would have wanted, but he neither had Lincoln’s political nous or his moral authority. It seemed to his many opponents that he merely wished to restore the old antebellum South. It was to lead to a vote for his impeachment which he only won by the narrowest possible margin.

Within ten years of the end of the Civil War and the emancipation of the slaves’ white rule had been re-imposed in most of the South. White plantation owners were employing cheap black labour in conditions almost as harsh as when they were in bondage, secessionist politicians were being re-elected to Congress, and white supremacists were sitting in the Governor’s Mansion.

The Ku Klux Klan which had been formed in Pulaski, Tennessee in May 1865 by ex-Confederate Army Officers was to play a significant role in restoring white supremacy in the Southern States and the policies of segregation that followed.

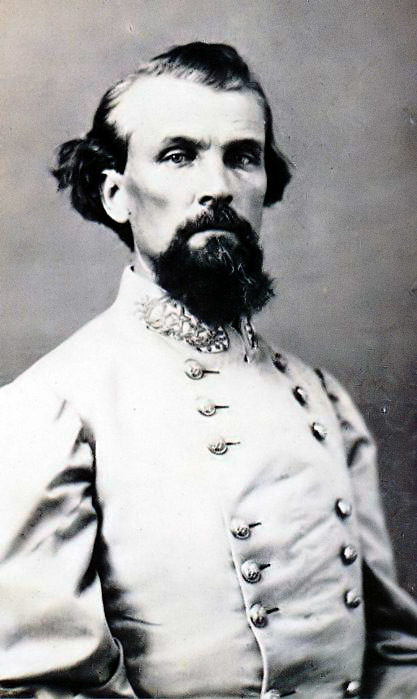

Initially it was seen as little more than a fraternal society but others soon began to perceive it as a nascent self-defence league and its popularity soon spread throughout the Deep South and by 1867 an organisation had been formed in Nashville to bring all the different branches together. Its first so-called ‘Grand Wizard’ was the legendary Confederate Cavalry Commander Nathan Bedford Forrest, an ex-slave owner and brilliant battlefield tactician who also became notorious during the war for executing any black man found under arms or captured in uniform.

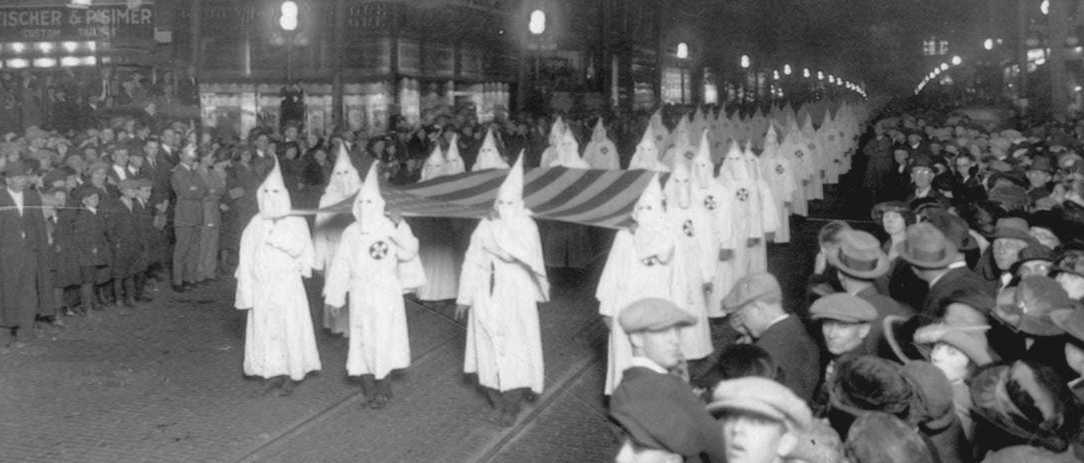

With such a charismatic figure at its head the Klan soon became integral in the fight to preserve the Old South and this fight soon turned violent as dressed in their distinctive uniform of white sheets and hoods they held rallies designed to cow the black population whilst Klan Night-Riders criss-crossed the countryside burning black owned farms, destroying crops, and lynching those who opposed them. Many hundreds of Negroes, carpetbaggers, and those deemed undesirable were assaulted and murdered in the years immediately following the end of the Civil War.

Such was the scale of Klan violence that President Ulysses Simpson Grant felt compelled to act and on 20 April 1871, he passed the Ku Klux Klan Act which proscribed the organisation, but it was already too little too late. With its work almost done, the Klan had already begun the process of disbanding itself whilst those that remained, forced underground, soon became known as the “Invisible Empire.”

By 1877, every Republican in the South had been removed from Office and replaced with white conservative and often white supremacist Democrats. But proscribed by law and seemingly no longer required it appeared that the Klan had ceased to exist, and for most Americans it had.

In 1915, the legendary movie director D.W Griffith, a native of Kentucky and the son of a Confederate Army Officer, released Birth of a Nation. It was a blockbuster in every sense of the word and received a rapturous reception.

Its story had been largely based on a book called ‘The Klansman’ which portrayed the Negro race as drunken, idle, untrustworthy and lascivious beasts with the Klan riding to the rescue of imperilled white womanhood. And this was how the movie was viewed though Griffith was later to say that he had wanted to depict the sufferings of the South in general.

Despite the criticism that was levelled at it in some quarters it was a box office smash and costing an expensive $110,000 it was to make in takings well over $60 million.

It was condemned by black organisations and in the liberal press for its crude and unmitigated racism but praised by President Woodrow Wilson who had a private viewing in the White House and was later heard to remark – thank God for the Klan.

Despite the endorsement of the President, Griffith was hurt by the criticism and in his next movie ‘Intolerance’ he tried to redress the balance, but it was a box office flop.

Birth of a Nation had been made at a time when racist murders in the South were on the increase. One of the more sensational occurred following the indictment on 23 May 1913 in Atlanta, Georgia, of Leo Frank, a factory manager, for the murder of 13-year-old Mary Phagan, an employee of the company. Frank was Jewish and Northern and though the evidence against him was circumstantial he was roundly condemned by the Southern press.

The case against him rested on the evidence of a black janitor, Jim Conley.

During the trial, Frank’s Defence Attorney Luther Rosser accused Conley of being a “dirty, filthy, drunken, lying nigger” and Frank during his own testimony asked the Jury how they could possibly believe the “perjured, vapourising of a black brute”. The attempt by Frank and his Defence Team to play the race card failed, however. Anti-Semitism was just as rife in Atlanta as was anti-black sentiment and Frank was found guilty and sentenced to death but because of the discrepancies in the police investigation the State Governor commuted the sentence to life imprisonment.

On the evening of 16 August 1915, Frank was abducted from his prison in Milledgeville and driven 150 miles to within sight of Mary Phagan’s grave and hanged. The drive had deliberately replicated Sherman’s March to the Sea during the Civil War.

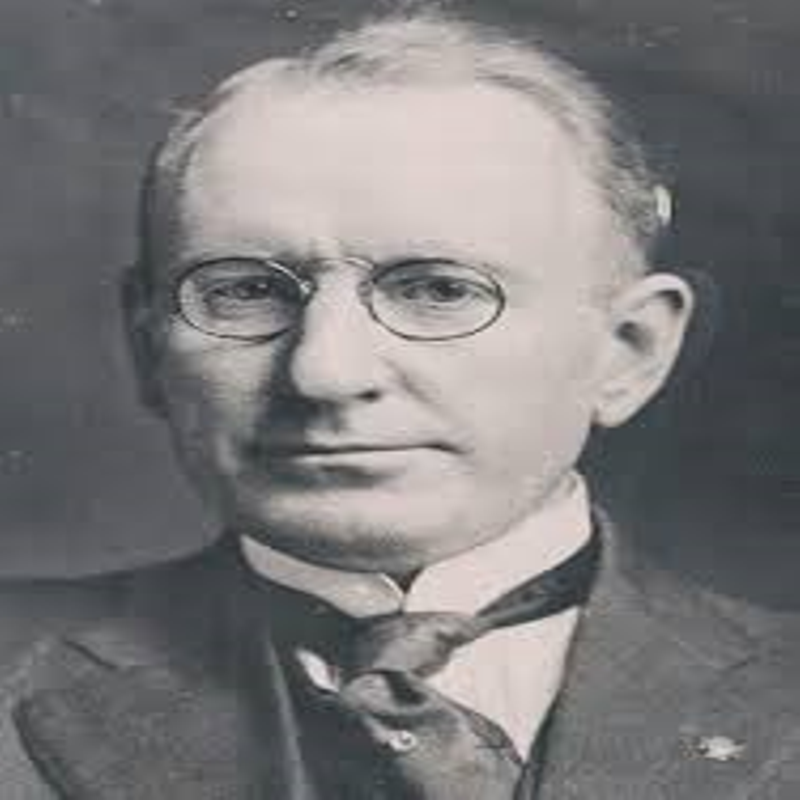

The release of Birth of a Nation along with the Frank incident played an integral part in the revival of the Klan. The Alabama physician and de-frocked Methodist preacher William Joseph Simmons was recovering from an accident when inspired by both events he decided to reform the Klan.

On the night of 16 October 1915, he led a group of men, many of whom had been present at the Frank lynching, up Stone Mountain overlooking Atlanta where they set fire to a large wooden cross. The burning cross could be seen in the city and for many miles around and was to become the most visible sign of Klan activity.

But this would not be the Klan of old. It no longer sought just to preserve and defend the status-quo. It now had a political agenda all its own - the Ku Klux Klan had been reborn.

The newly reconstituted Klan stood to protect native born, white, Anglo-Saxon Protestants. It was opposed to Roman Catholics, who owed their allegiance to the Pope, a foreign despot; Jews, who were Christ-killers; and Negroes, who were racially inferior. They were also anti-Communist which was an atheist ideology; anti-Immigrant who were leeches on American society; and anti-Labour who were opposed to the free-market and the pursuit of the American dream.

It espoused Christian family values, the Protestant work ethic and cherished white womanhood while supporting the temperance movement and prohibition. This was the new Klan, no longer invisible they were now political and very visible, and they would soon become national. They wanted power and they made no bones about it.

The 1920’s were to be the high-water mark of Klan support, and it was soon to spread from its Southern heartland to the mid-West and much of rural America though its headquarters remained in Dallas. Its increased popularity was mainly down to two factors: It had been steadfast in its support of the Temperance League and fully backed the 18th Amendment and the passage of the Volstead Act of 28 October 1919 that banned the production, distribution, purchase, and consumption of alcohol anywhere in the United States. The Klan received a great deal of Kudos for its strict moral stance. They also exploited the resentment of those white soldiers, unemployed veterans of the Great War, who had been willing to put their life on the line for their country only to see their jobs go to blacks willing to work for lower wages. It was a complaint the Klan exploited to the full and farm burnings and lynching increased. The Klan denied any involvement of course, and for the first time perhaps, many were willing to believe them, or at least give them the benefit of the doubt.

In November 1922, William Simmons was ousted as Imperial Wizard by the Alabama dentist, Hiram W Evans. He took over at a time when there seemed to be no stopping the Klan. No longer just a regional and rural organisation it was now making great headway in the cities of the north. In Detroit alone it could boast 40,000 members, and by the end of 1924 it had six million members nationwide, or some 15% of the adult population.

The Ku Klux Klan was affiliated to the Democratic Party and at its 1924 National Convention to elect a Presidential Candidate it got the opportunity to flex its new-found political muscle.

In what was to become known as the ‘Klanbake’, Evans and the Klan leadership refused to support the front-runner, the Catholic Al Smith instead supporting his rival, William G McAdoo. Their opposition led to deadlock and for over a week the dispute dragged on with the Klan holding night time rallies outside the Convention Hall in full regalia and with burning crosses while inside the Convention Hall itself temperatures ran high and fist fights broke out.

The bad publicity was excruciating for the Party and after 103 separate ballots the issue remained unresolved. Such was the embarrassment that the three times Presidential Candidate William Jennings Bryan was drafted in to negotiate a deal and the Klan eventually agreed to support a compromise candidate, John W Davis. But they had made their point and the next time they would choose the nominee.

By the end of 1924, the Ku Klux Klan appeared to be the rising political power in the land.

They represented, or so it seemed, the values of the white Protestant working class – God, sobriety, hard work, and the preservation of a traditional way of life free from foreign influences. But it was all a sham and within four years of the Klanbake the whole rotten edifice of the Invisible Empire would be brought crashing to the ground and one man alone would be responsible – David Curtiss Stephenson.

D. C. Stephenson as he was known was born in Houston, Texas, on 21 August 1891. Little is known of his early life but by the time he arrived in Evansville, Indiana, in 1920, he had already been a member of both the Socialist Party and the Democratic Party. Having settled in Indiana he now joined the Ku Klux Klan.

An able administrator and charismatic speaker whose brand of blue-collar populism went down a storm with the farmers of the largely rural State, he quickly rose through the ranks of the party to become Grand Dragon. Under his leadership membership of the Klan in Indiana rose to an all-time high of 250,000.

He had also backed Hiram J Evans in his bid to become Grand Wizard and his reward for doing so was to be made the Grand Dragon of 22 other Northern States.

D.C. Stephenson, or Steve as he was known, seemed to epitomise everything that people admired about the new Klan. He was sober, hard-working and a committed Christian. He even eschewed violence, denounced the burning of crosses, and was heavily involved in many community programmes. But the truth was very different, and he was to prove to be none of these things.

At a party thrown by Ed Jackson, the Republican Candidate for Governor, he met a 29-year-old school teacher Madge Oberholtzer, who ran a literacy programme in the State.

Stephenson soon became obsessed with the sexually naive Madge who despite wanting to be associated with such a powerful man who she knew could help advance the programme she felt so passionate about repeatedly spurned his advances. Frustrated by his inability to woo Madge, Stephenson decided to take what he wanted instead.

He invited her to meet him at his home on the pretext of discussing the help he could provide her. She was reluctant to go but could not turn down such a golden opportunity. Upon her arrival Stephenson plied her with alcohol, drugged and kidnapped her.

On 15 March 1925, on a train journey to Chicago he repeatedly beat and raped her. In doing so, he bit her all over her body to such an extent that someone who saw her later said that she looked as if she had been chewed by a cannibal.

While they were in Chicago, she managed to slip away long enough to purchase some mercuric chloride tablets with which she hoped to commit suicide. She failed and instead became seriously ill and for days she writhed and screamed in agony. Rather than take her to a doctor which may have saved her life Stephenson left her to suffer before telling his accomplices to take her back home to Indiana. Before they did so Madge threatened him with the law, to which Stephenson laughed and replied: “I am the law in the State of Indiana.”

Returned home, Madge immediately sought urgent medical attention but it was too late and on 15 April 1925, she died in great pain of kidney failure brought on by mercury poisoning. Before doing so however, she made a death-bed deposition. It was enough to bring a case of second-degree murder against D.C Stephenson.

Stephenson’s demeanour in the Courtroom shocked many for he was both arrogant and cocksure not believing for one moment that an all-white, male jury, many of whom were or had been Klan members, would ever convict him. He also knew that most of the political establishment in Indiana were on the Klan’s payroll. He also knew they knew he had the evidence to prove it.

The Trial made national headlines and as the details of it began to emerge public sentiment began to turn against him and the Klan. Soon members began deserting the organisation in droves.

In an effort to stem the tide Hiram J Evans began to distance himself from Stephenson before finally denouncing him outright and in August 1925, he led 40,000 fully robed Klansmen down Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, in a show of strength.

But with Party membership diminishing with every new revelation, it was apparent that the Klan was in terminal decline.

In Court D.C Stephenson was revealed to be a violent, drunken lecher. The man who had seemingly epitomised everything good about the new Klan had been a fraud, the paragon of all its virtues had become the purveyor of vice. On 14 November 1925, he was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Still, he expected to be pardoned by the Governor Ed Jackson, when this did not happen he handed over for publication all of the documents he had relating to the corrupt relationship the Klan had with leading politicians throughout the States he controlled. If he was to go down then he would take everyone else with him, and that included the Klan.

Within four years of Stephenson’s conviction Klan membership in the United States had fallen from over 6 million to under 30,000. Unable to halt the decline in 1939, Hiram J Evans sold what remained of the Klan to the Indiana vet James A Colescott, a Nazi sympathiser.

Under his leadership Klan membership declined even further as they became associated with attempts to disrupt the American war effort after Pearl Harbor and in 1944, the Inland Revenue Service filed for $685,000 in back taxes from what was left of the Klan. With no possibility of meeting such a demand Colescott was forced to wind the organisation up. It seemed that the Ku Klux Klan was finished – but it wasn’t of course, and would have yet another revival.

On 1 December 1955, in Montgomery, Alabama, Rosa Parks, a 43 year old black seamstress refused to give up her seat on a bus to a white man. She wasn’t the first black woman ever to do so but the mood in the Deep South had changed and on this occasion the incident made headlines around the world.

Arrested and forced to leave the bus she was later convicted of breaking the law and fined but the consequences of her actions were to be far more profound for they sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

The boycott of Montgomery’s buses by the black population was to lead to a Supreme Court ruling that judged Montgomery’s segregation of its buses to be unconstitutional. The Supreme Court’s ruling was the first dent in the South’s policy of racial apartheid. The boycott was also to see the emergence on the scene of a young Baptist Minister, Martin Luther King and the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement.

Rosa Parks protest had also occurred just four months after a fourteen-year-old black boy, Emmett Till, had been murdered in Mississippi for whistling at a white girl. The Deep South remained a dangerous place for the Negro who stepped out of line.

The emergence of the Civil Rights Movement was to bring in its wake a revival in the fortunes of the Ku Klux Klan. Whereas the former sought to change the South and create an even playing field for all the length and breadth of the country, the latter was just as determined to preserve the privileged status of the white population in the South.

The central plank of the Civil Rights Movement was voter registration. The majority of Negroes in the South were effectively disenfranchised. For example, in Mississippi where blacks made up 41% of the population only 2% were eligible to vote. They were second class citizens in their own State and their own country, and if they were prevented from voting they would remain so.

Martin Luther King and the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (N.A.A.C.P) were determined to change this. In the early hours of the morning of 21 June 1964, three civil rights workers, two young Jewish men, James Goodman and Michael Schwerner, and a black man, James Chaney, were stopped for speeding in Neshoba County, Mississippi, by Deputy Cecil Price. After spending a night in the cells, they were released and escorted to a spot near the County Line by Deputy Price. There they were ordered to stop and wait as the local Klan gathered. A little later they were dragged from the car and severely beaten before being shot to death and buried in a lime pit.

After months of frenzied investigation carried out under the spotlight of intense media scrutiny the FBI made a number of arrests. Aware, that they would be unable to secure a conviction for murder in a Mississippi Court the accused were instead tried on the lesser Federal charge of depriving the victims of their civil rights.

Found guilty, Cecil Price, Imperial Wizard Sam Bowers, and five others were sentenced to between three and ten years in prison. None were to serve more than six.

Earlier on 12 June 1963, Medger Evers, a native of Mississippi and a Second World War veteran was murdered outside his house by Klan member Byron de la Beckwith. Evers had been prominent in the Civil Rights Movement and the Field Representative for the N.A.A.C.P in the State. His murder caused an outcry throughout America. Even so, and despite the overwhelming evidence against him Byron de la Beckwith was not brought to justice until 1994.

In the summer of 1963, the Governor of Alabama George Wallace spoke of the need for more funerals to stop this damned desegregation. This was said hot on the heels of his notorious declaration: “Segregation Now, Segregation Tomorrow, Segregation Forever.”

On 16 September 1963, the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, a centre of local civil rights activity, was dynamited. Four young black girls, 14-year-old Addie Mae Collins, Carole Robertson, Cynthia Wesley, and Denise McNair, aged just 11, were killed.

The explosives had been set by Thomas Blanton, Herman Cash, Bobby Frank Cherry, and Robert Chambliss, all members of the United Klan’s of America.

This fact was well known at the time and appears to have been widely circulated locally. Despite this the crime was to remain officially unsolved until 1977, when Chambliss was at last convicted. He was to die in prison. Cash had already died earlier, and Blanton and Cherry were not tried until the year 2000.

In May 1963, the so-called Freedom Riders left Washington in buses bound for the South. White and black students travelled together as the idea was to challenge the concept of segregated interstate travel.

As the buses approached Birmingham, Alabama, they were attacked by furious mobs hurling bricks, bottles, and petrol bombs. Meanwhile the local Police Chief Eugene “Bull” Connor had arranged with the Klan a 15-minute window of opportunity for them to attack the students as they left the buses upon their arrival in Birmingham before the police would intervene. They took their opportunity with relish savagely beating the students with baseball bats and iron bars. Many of those injured were later refused treatment in the city’s hospitals.

As narrow-minded in their actions as they were bigoted in their views, Klan violence only served to hasten the end of segregation, the very thing they had vowed to defend.

On 2 July 1964, President Lyndon Baines Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act securing equal rights for all American citizens. Despite its defeat the Klan did not go away, and sporadic acts of violence were to continue for many years to come.

In recent times however it has been overshadowed by the emergence of white supremacist paramilitary groupings, the so-called Militia, conspiratorial and with a grievance against the Government.

This grievance would culminate in the bombing of the Alfred P Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City on 19 April 1995, that killed 168 people and seriously injured a further 680. The bomb had been planted by army veteran and Militia member Timothy McVeigh and was the worst ever terrorist atrocity on American soil before 9/11. McVeigh, who refused to appeal against his sentence of death, was executed by lethal injection on 11 June 2001.

The Ku Klux Klan still exists as an active organisation today though it has around only 6,000 members. During the 1990’s it underwent a makeover under the leadership of the articulate, charismatic, media-savvy David Duke, and moved more into the mainstream. Even so, it has made few political inroads.

No longer restricted in its message to burning crosses on distant mountain tops it has since sought to create links via the World-Wide Web with other Far-Right groups in the rest of the world, particularly Europe.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous

Share this post: