Kristallnacht: Night of the Broken Glass

Posted on 30th June 2021

On 28 October 1938 the Nazi Government in Germany deported those German Jews they defined as being of foreign extraction and some 12,000 who had been born in Poland were ordered to pack a suitcase, vacate their homes and put upon transports bound for the Polish border.

Upon their arrival the Polish Authorities permitted only 4,000 of them to enter the country to join their families while the rest were left to wander the villages along the frontier, homeless, penniless and forced to beg for food and shelter. Among these refugees were Zindel and Rivka Grynzspan who had left Poland and relocated to Hanover in 1911.

Their 17-year-old son Herschel was staying with his uncle in Paris when he received a harrowing letter from his sister Berta detailing the dire situation his parents now found themselves in and begging him to send money. Instead, he used the little money he had to purchase a pistol and some ammunition.

On 7 November he visited the German Embassy and asked to speak to an official.

After waiting for some time he was taken to the office of the diplomat Ernst von Rath who greeted him warmly, but once in his presence and without saying a word he took out his revolver and shot him five times. Von Rath died the following day. Following the shooting Herschel made no attempt to escape but waited calmly in the office for the arrival of the police to whom he gave himself up and confessed everything.

Ironically Herschel had taken out his vengeance on a man who was a vocal critic of the Nazi Regime and was under investigation by the Gestapo.

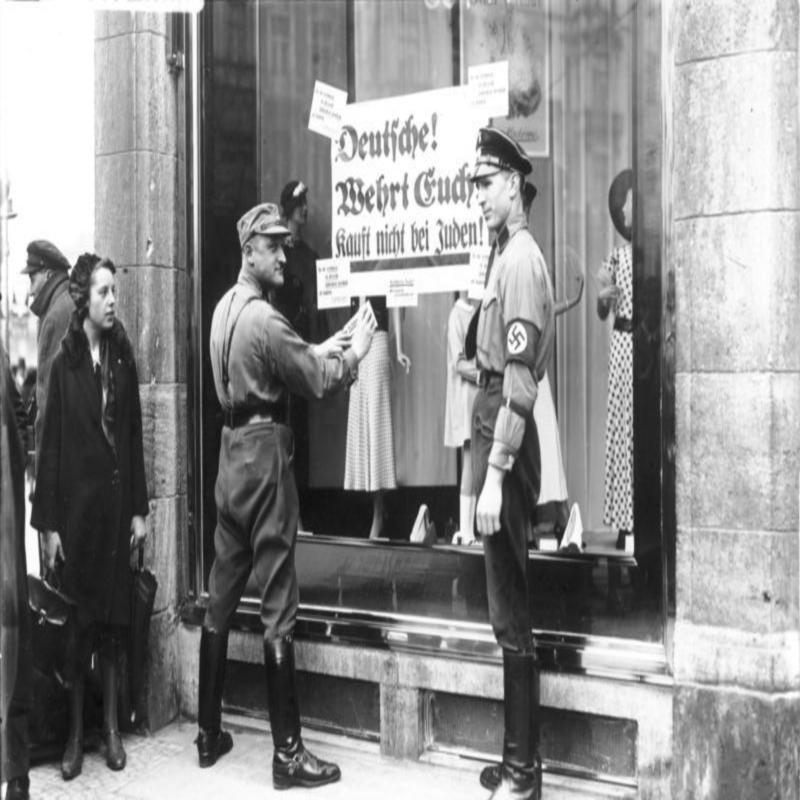

Within days of coming to power the Nazis had encouraged a boycott of German shops and businesses but it had been poorly received by the public and ever since Hitler had used the law to exclude Jews from German society.

On 7 April 1933, the Law for the Restoration of a Professional Civil Society banned anyone of Jewish origin from working in Government service and forced those already employed to resign.

On 15 September 1935, the Nuremberg Laws defined who was to be considered Jewish and then stripped them of their German citizenship. It also banned marriage and sexual relations between Jews and non-Jews and there was yet another only partially successful boycott of Jewish shops and businesses.

This infuriated the Nazi’s who despite all the relentless anti-Jewish propaganda remained perplexed by the ordinary German's insistence on calling their Jewish family doctor, buying their sausages from the local Jewish butcher, and having their clothes made by their Jewish tailor.

They remained frustrated by their inability to unleash the full fury of the German people against the Jews, but no reason had yet been found to do so. The murder of a German diplomat in a foreign city by an emotionally disturbed Jewish youth provided them with just the pretext they required.

News of von Rath's death on 9 November reached Berlin around ten o’clock the same night and within two hours anti-Jewish riots had already broken out throughout Germany. Such a speedy response to the news was indicative of how much work had been made in preparation for just such an event.

Yet it was important for the Nazi's that the riots appeared the spontaneous rage of the German people against the alien Jewish presence in their midst. So, among the crowds that gathered on the streets were SA and SS men dressed in civilian clothes armed with sledgehammers, petrol and matches. Their job to destroy Jewish property and where there was no angry crowd to create one.

The preparations for Kristallnacht had been made by the Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels who had been out of favour with Hitler ever since his wife Magda had brought his affair with the Czech actress Lida Barova to the Fuhrer's attention. This was his opportunity to once again become part of the Fuhrer’s inner-circle.

By the early hours of 10 November, the riots had spread to almost every major German town and city and the dark night sky was lit up by the flames of burning Synagogues and the still air rang to the sound of breaking glass.

Jewish homes were broken into, and their occupants dragged out and beaten, passers-by of Jewish appearance were attacked in the streets and young Jewish men targeted for arrest.

Jewish shops were occupied and cordoned off to prevent looting not to protect the property of their owners but because the Nazi’s did not want the riots to be seen as anything but the expression of the German people’s wrath against the Jew.

The atmosphere in many places was as much one of celebration as it was hate as millions of Germans came onto the streets not to participate but to simply cheer and applaud with any brave enough to express their disgust doing so at very great risk to themselves.

By the end of the night as many as 1,000 Synagogues had been set alight and destroyed, 7,000 Jewish owned businesses had been occupied and had their windows smashed, and 29 Department Stores had been ransacked. Jewish cemeteries had also been desecrated and as many as 30,000 Jews had been arrested and sent to the Concentration Camps at Sachsenhausen and Buchenwald.

The official total of deaths given was 91 though the actual figure is believed to have been at least 800 and may have been as many as 2,000.

The events of Kristallnacht had been nothing but an old-fashioned anti-Jewish pogrom as crude as anything that might have been seen in Tsarist Russia.

No one could any longer doubt that Nazi intentions towards the Jews were hostile or that this was a government which abided by the rule of law.

The anti-Nazi diplomat Ernst von Rath was given a much-publicised State Funeral that was attended by Hitler himself and the Jewish community fined 1 billion marks for the murder. They were then ordered to pay a further 4 billion marks to pay for the clean-up following Kristallnacht. To ensure that the money was paid it was levied at 20% of all Jewish businesses and property.

Prior to Kristallnacht many people had believed that the rabid anti-Semitism of the Nazi's would pass with the responsibility of power. That it was merely a crude tool with which to court popularity.

Few people thought so any longer including a great many Jews who having seen outbreaks of virulent and often violent anti-Semitism come and go in the past believed that the Nazi phenomenon would be the same. In the months following Kristallnacht tens of thousands of those Jews remaining in Germany fled.

The unintended irony of the Nazi pogrom on the Night of the Broken Glass is that so many lives were probably saved as a result.

Tagged as: Modern

Share this post: