Lord Kitchener: Your Country Needs You!

Posted on 12th March 2021

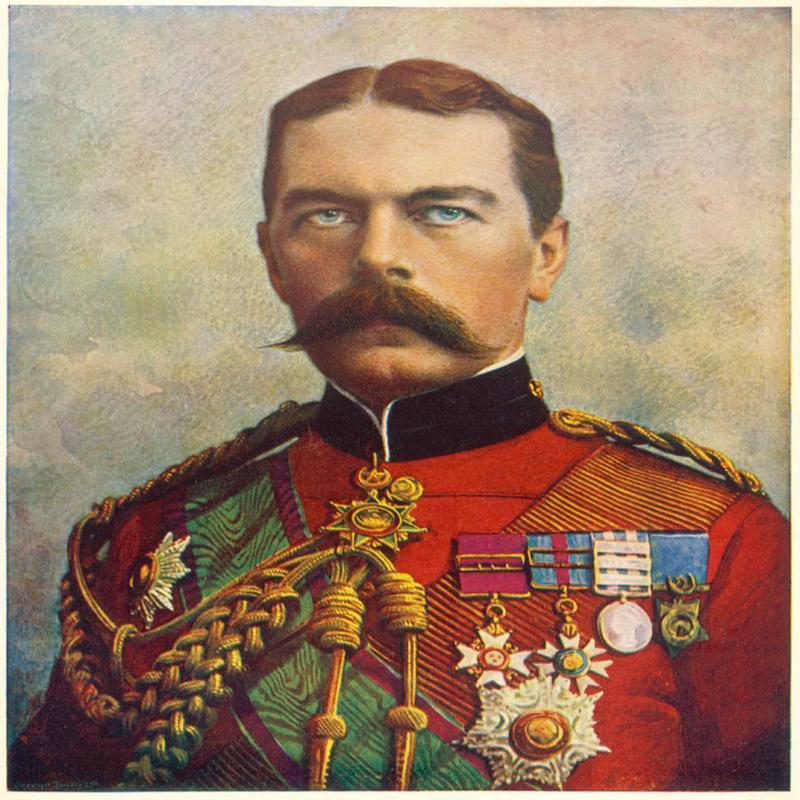

Horatio Herbert Kitchener was to become a British hero and a Victorian icon; he was to avenge General Gordon, defeat the Boers and become the face of the recruitment drive in the Great War and by doing so generate the most famous poster of all time.

As one of Britain’s most decorated soldiers his fame spread throughout the world while as Minister of War he was beyond reproach. Yet his death greeted with shock, disbelief and regret by the public was met with a huge sigh of relief by those in political power.

He was born in Ballylongford, Ireland, on 24 June 1850 to English parents but raised and schooled in Switzerland where his family moved soon after. His father who had been a Colonel in the British Army encouraged him to take an interest in military affairs and upon returning to England he was to follow in his footsteps and enlist in the Royal Engineers but very quickly becoming bored with parade ground life volunteered to serve in the Middle-East.

It was in the Middle East and later Africa that he was to make his name soon rising to co-command an expedition to survey the area around Palestine and modern-day Israel. Always a secretive man he is believed to have been involved in espionage and to have served as a conduit for General Gordon during his ill-starred Sudanese campaign. He was later to receive a commission in the Egyptian Army where his reputation grew rapidly so much so that by the time it came to avenge General Gordon’s defeat at Khartoum, he was the natural choice to lead the army.

Fourteen long years had passed since the death of Gordon and the decision to recover the Sudan was taken for geo-political reasons not that the public viewed it that way and even though the Mahdi had long since died and the Sudan was ruled by his nominated successor the Khalifa it was for them a campaign of revenge.

Kitchener was given command of an Anglo-Egyptian Army of 23,000 men around 8,000 of whom were British. He led his army down the Nile, the British by boat the Egyptians on foot to the village of Omdurman which he fortified and where he knew he could be supported by the guns of the ships moored on the river.

On the morning of 2 September 1898, his army was attacked by more than 50,000 Sudanese tribesmen fired by Islamic zeal but faith alone would count for little on an open desert plain blasted with shot and shell and swept by gunfire. In a battle that was to last the best part of a day and was fought in choking dust and an intense heat repeated frontal assaults by the Sudanese were repulsed time-and-again. By the time the sun set 9,700 Sudanese lay dead, a further 13,000 had been wounded, and 5,000 captured; for the cost of only 48 Allied dead and 340 wounded.

Gordon had been avenged, the Khalifa defeated, and British honour restored, Kitchener had achieved a great victory and was acclaimed back in Britain as a national hero but his actions in the immediate aftermath of the battle were later to come in for much criticism. He had ordered that all the Sudanese wounded incapable of moving of their own volition were to be killed and that in order to save on bullets the bayonet was to be used. One of his severest critics was the young Winston Churchill, who had fought in the battle and had been appalled at such casual brutality displayed toward a gallant foe.

Despite his reputation for callous indifference however, his brief Governorship of the Sudan was surprisingly liberal and accommodating. Interested in restoring order as quickly as possible he instructed that the Mosques should be rebuilt, Islam be recognised as the official religion, and he curbed incursions by Christian missionaries.

Not long after his victory at Omdurman on 18 September 1898, Kitchener became involved in what was come to be known as the Fashoda Incident.

A French Expedition under Major Marchand had been spreading French influence throughout West and East Africa for the previous ten months and had reached as far as the Nile Delta. They had never accepted the effective British occupation of Egypt and therefore control of the Suez Canal, and they were determined to undermine it wherever they could. Likewise, the British were looking to link their possessions in South Africa with those in the East. Indeed, it was the dream of Cecil Rhodes to construct a railroad across Africa that would provide the Cape Territories with access to an East Coast port and the sea. A pivotal link in these competing ambitions was the Sudanese town of Fashoda and Major Marchand was ordered to establish a base there and declare it a French Protectorate. This was something that Kitchener was unable to tolerate, and he marched a force there to confront them. In what for a time was a tense stand-off it appeared that war between the two countries was imminent as the events at Fashoda blew up into a full-blown diplomatic incident but Marchand who with only 120 men was never really in a position to fight, wisely backed down and withdrew from the town.

It appeared to those back in Britain that Kitchener had not only avenged the Mahdi’s murder of Gordon but had also stood up to and humiliated the French. - his reputation soared.

On 11 October 1899, the Boer Republics of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State in South Africa responded to British demands by declaring war on the Empire and within weeks the garrisons at Ladysmith, Mafeking, and Kimberley were under siege but reinforcements under the command of General Sir Redvers Buller were on their way.

The British had expected a swift victory but a series of morale sapping defeats at Magersfontein, Colenso and Stormberg Junction in what became known as “Black Week”, was to see the Sir Redvers quickly renamed Sir Reverse.

The mighty British Empire it seemed was being humiliated by 30,000 Boer farmers and it was to cost Buller his command. In January 1900, he was replaced by Lord Frederick Roberts who chose as his Chief-of-Staff Horatio Herbert Kitchener.

Roberts greatly reinforced quickly relieved the besieged garrisons and in June captured Pretoria, the capital of the Transvaal. By September 1900, the regular Boer army had been defeated and both Republics were under British control. The Boers, however, did not surrender as expected but instead engaged in a protracted and increasingly brutal guerrilla campaign. Still, in November 1900, his work done, Lord Roberts handed over command in South Africa to his subordinate Kitchener.

Frustrated that he could not bring the Boers to battle in any conventional sense Kitchener devised a system that was designed to squeeze the life out of Boer resistance. He constructed barbed wire fences punctuated with garrisoned block houses to hem the Boers in. He then ordered that all Boer farms be burned, their crops destroyed, and their livestock slaughtered. Boer families that had been removed from the farms were herded into what were in effect the first Concentration Camps.

The British Army was ill-prepared to run such camps. Food was scarce, sanitation minimal and medicine in short supply. Though conditions were to improve by the war’s end more than 28,000 of the Boer internees had died of starvation and disease, or 35% of the total incarcerated most of them children. Indeed, more than twice as many Boers died in British captivity than were killed in the fighting itself.

Though it had never been intended that anyone should die in the Camps they were a stain upon the reputation of the British Empire and a large part of public opinion at home had turned against the war as a result. But as far as Kitchener was concerned it had been necessary and moreover it worked. On 31 May 1902, the Boers signed the Peace Treaty of Vereeniging and surrendered their arms. Kitchener was lauded as the victor of the Boer War but even now controversy dogged him. He had earlier become embroiled in the Breaker Morant episode.

Harold “Breaker” Morant, though born in England had lived in Australia for many years and along with Lieutenant Peter Hancock and thousands of other Australians had volunteered to fight for the British in South Africa. The Australians, however, were notorious for disobeying orders and not showing their British Officers due deference. When Morant and Hancock were arrested for killing Boer prisoners-of-war they were not seen to have done anything that wasn’t already common practice. Nevertheless, they were both court-martialled and condemned to death, a sentence that was widely seen to have been political and intended to teach the ill-disciplined Australians a lesson.

An appeal of clemency for both Morant and Hancock was turned down by Kitchener who personally signed the death warrants.

Following the successful conclusion of the Boer War, Kitchener was appointed Commander of British Forces in India 1902-1909 and then Military Governor of Egypt 1911-14.

In 1910, he was promoted to Field Marshal and four years later became Lord Kitchener of Khartoum.

Field Marshal Horatio Herbert Kitchener was heading towards the sunset of his life and glorious retirement when in the summer of 1914, Britain once again found herself at war this time in a life and death struggle that would stretch it to breaking point. Who better to turn to in a moment of crisis than Britain’s greatest living soldier, the British Prime Minister Herbert Asquith appointed him Minister of War. His first task was to raise an army.

He had earlier warned the Cabinet that no one was going to be home by Christmas and that this was to be a long war where the casualties would be counted not in the tens but the hundreds of thousands. There was no way that Britain’s small regular army that was mostly stationed abroad protecting the Empire could possibly cope in such a conflict. His warnings were not well-received, but they were at least listened to, and a massive recruitment campaign, one of the most successful in history, was now launched.

The campaign itself was to produce the poster which would become famous around the world and achieve an iconic status all its own. It pictured the stern face of Lord Kitchener staring with a look of grim determination his finger pointing directly at the viewer and demanding – “Your Country Needs You!”

It was the creation of the artist Alfred Leete and first appeared in the September 1914 edition of the influential magazine London Opinion and was to prove such a powerful image that it was quickly adopted by the Government and distributed the length and breadth of the country appearing on billboards, at railway stations, in shop windows, on the side of trams and many other places.

Kitchener sweetened the recruitment drive by promising that anyone who volunteered would be able to serve with his friends. It worked like a dream and over the next eighteen months more than three million men enlisted in the so-called Pals Battalions.

This was to be Kitchener’s Volunteer Army, but it would take time to make them battle ready. First this army would have to be organised into viable fighting units and then these millions of men would have to be trained. Also, British working-class men were also undernourished so they had to be properly fed and then put through an intensive exercise regime to make them physically stronger.

Despite the success of his early recruitment campaign Kitchener was not much admired or much liked by those who had to work with him. He was a stiff-backed soldier used to being obeyed who was brusque in his manner, coarse in his language, unsympathetic and deaf to criticism. He would only delegate power where necessary and his perceived arrogance was to make him a great many enemies. People were quick to unfairly blame him for the myriad failings and blunders of the early months of the war.

Much has also been made of Kitchener’s alleged homosexuality. It is true that he never married or fathered any children and that his constant companion was Captain Oswald Fitzgerald and a journalist remarked at the time that Kitchener “has the failing acquired by Egyptian Officers, a taste for buggery.” He always had a cadre of young unmarried Officers around him that became known as “Kitchener’s Band of Boys”. He also enjoyed interior design and collected fine china considered unmanly pursuits and was said to have an artistic temperament which was Victorian code for homosexual.

There is little doubt that he enjoyed the company of young men and had no obvious interest in women, and it was not unknown for him to dismiss them from his presence even so there is little evidence that he ever buggered anyone.

As we have seen, Kitchener soon became the focus of blame for all the failings of Britain’s war effort, at least among those who counted. He was criticised for lacking strategic vision and being out of touch. Such criticism seems not only harsh but as much the result of his prickly personality as his performance as Minister of War.

In 1915, the so-called Shell Crisis hit the headlines. It had emerged that the British Army on the Western Front had not only been provided with too few shells but those it did have had insufficient high explosives to be effective. The story had first been published in the Times Newspaper and had been largely ignored but was later republished in the Daily Mail under the sensational headline “Lord K’s Tragic Blunder”. It caused outrage, not because of the Shell Crisis but because it had dared to criticise the great and heroic Lord Kitchener. Though he was not held responsible by the British public he was certainly blamed in political circles and responsibility for munitions was removed from his control and given to the Liberal politician, David Lloyd George.

Kitchener was being increasingly blamed for the stalemate on the Western Front, but such was his popularity and his iconic status that he was an impossible man to remove. In January 1916, he was sent on a tour of inspection of the disaster that had become the Gallipoli Campaign. It didn’t take him long to realise that a catastrophic defeat was looming and he ordered an immediate withdrawal. By doing so some of the blame for it rubbed off on him even though he had opposed the operation from the start. In the meantime, in his absence moves were underway to remove him.

Would he, they wondered, accept becoming Viceroy of India? No, was the answer. The truth is they couldn’t remove him, they could only ask him to go. It was a difficult situation for he was seen more as an impediment than an asset to the war effort. In the summer of 1916, it was decided to send Kitchener on a diplomatic mission to Russia.

The Russians had recently suffered a series of devastating defeats and their ability to continue the struggle was being seriously questioned. Any Russian withdrawal from the war would be a disaster for the Western Allies so Kitchener was being sent on a morale boosting mission, to cast his eye over Russian strategy, and suggest ways that Britain could help.

Others of a more cynical bent suggested that it was just an excuse to get him out of the country.

On 5 June 1916, Lord Kitchener travelled north to the Orkney Isles where the following day he boarded the Armoured Cruiser H.M.S Hampshire bound for Russia.

At 17.30 on 6 June, just off the coast of the Orkney’s in a Force 9 Gale the Hampshire is believed to have hit a mine. It blew up and sank in less than ten minutes. Lord Kitchener, his companion Captain Fitzgerald, all of his staff, and 643 of the 656 men aboard went down with the ship. Those few survivors who had managed to struggle ashore were instructed never to speak of the incident.

The few men who claimed to have seen Kitchener in his final moments stated he had met his end with fortitude and resolution and had made no effort to escape the sinking ship.

The fate of the Hampshire has since been the cause of a myriad number of conspiracy theories; was it deliberately torpedoed on the orders of the British Government? Was it sabotaged by the Irish Republican Brotherhood which had previously made threats on Kitchener’s life? Or had a bomb been planted by disgruntled Boers still looking to avenge the Concentration Camps? All have been suggested as reasons why the Hampshire met the end it did, but the truth is that a minefield had recently been laid in the area and that the Hampshire was just unlucky. Either way, the British Political Establishment breathed a huge sigh of relief. To paraphrase the Prime Minister’s wife Margaret Asquith, Lord Kitchener died a great poster but not a great man.

Just a month after his death, the Volunteer Army that he had done so much to recruit and make combat-ready, Kitchener’s Army, had its first real test at the Battle of the Somme. They performed well but at great cost. On the first day alone, there were 60,000 British casualties, 21,000 of whom were killed.

His creation of Pals Battalions also impacted on communities back home as large numbers of young men from the same town, village, and workplace were wiped out.

Lord Kitchener was a great hero to the British people in his own time even if not always to the Military High Command and Political Establishment he served; and both his reputation as a soldier and a politician have been frequently reassessed since his death but despite the frequent revisions one thing has remained constant – that poster.

Share this post: