Lucrezia Borgia: Lust, Jealousy, Poison and Murder

Posted on 6th September 2021

To the French novelist Victor Hugo she was the most hideous, the most repulsive, and the most complete moral deformity and Lucrezia Borgia remains even to this day one of the most vilified women in history. But was she the amoral poisoner of legend or merely herself a victim of malicious gossip? And If she did kill what drove her to do so – was it on the orders of her father, was it out of fear of her brother, or did she kill out of feelings of jealousy and lust?

Lucrezia Borgia was born in Subiaco, Italy, on 18 April 1480, the illegitimate daughter of the Spanish Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia and his long-time mistress Vanozza dei Cattanei.

Although Rodrigo’s many affairs and illegitimate brood were hardly a secret, celibacy within the priesthood meant for appearances sake that Lucrezia was raised away from the family home by a distant relative Adriana de Mila under whose tutelage she blossomed; with an inquiring mind, a deep love of the arts and the demands made on her negligible her early life appears to have been idyllic but she was also inculcated with the Borgia family loyalty. But it was little called upon in her formative years and life for Lucrezia was fun trying on and swapping clothes with her friends.

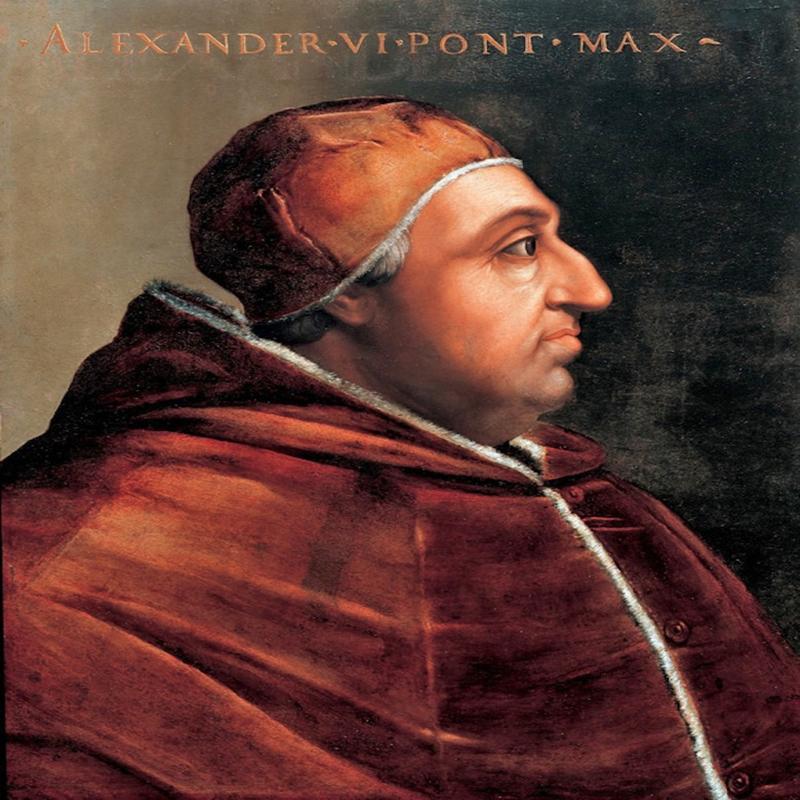

All this was to change on 11 August 1492, when her father bullied and bribed his way to the Papacy as from now on regardless of personal feeling or desire, she would be a pawn in the intricate machinations of Renaissance politics.

She had first been betrothed at the age of just 11 but the engagement had been cancelled following her father’s elevation to be Pope Alexander VI. A series of other such commitments were also annulled as being inadequate for the young Lucrezia as she was now touted around the great families of Europe.

Despite the desire to exploit his daughter’s value in the marriage bed Rodrigo could not bear to see her leave for, he doted on the pretty young Lucrezia, and their relationship was both a close and intimate one. Indeed, it was rumoured that a secret corridor existed leading from his bedchamber to hers and they certainly spent a great deal of time in each other’s company. Her brother Cesare was no less besotted with his sister and Lucrezia similarly with her other brother, Juan. They were as inclusive s a family as could be, possibly incestuously so.

In February 1493, her father settled upon Giovanni Sforza, Duke of Pesaro, as Lucrezia’s future husband and they were married in June the same year.

The wedding celebrations were as lengthy, extravagant and joyous as befitted a Borgia even if the marriage itself was not. It was first and foremost a marriage of convenience and as Sforza’s political cachet diminished and the relationship itself began to disintegrate so Lucrezia who had little time for her dullard husband and Cesare who was jealous that someone else was sleeping with his sister together conspired to be rid of him.

The Borgia family demanded that the marriage be annulled but Giovanni refused. He loved his wife, he declared, even if that love was not reciprocated. The Borgia’s were furious and in fear for his life Giovanni fled Rome accusing Lucrezia of having slept with both her father and her brother.

Lucrezia now visited her husband in Pesaro and using her undoubted charm managed to persuade him to return to Rome. There, in the menacing presence of Cesare he was coerced into signing the divorce papers.

The reason given for the annulment was Giovanni’s impotency. Even though Lucrezia was by now six months pregnant and the divorce proceedings demanded that she appear before the College of Cardinals to prove her virginity. Permitted to wear a veil to preserve her dignity it is possible she had a double stand in for her for as heavily pregnant as she was the physical examination found her to be virgo-intacta. Immediately the physical examination was completed Lucrezia was ushered off to a convent.

Her time in the convent was not one spent in religious devotion instead she began an affair with a handsome young Spaniard Pedro Calderon a popular messenger of the Pope’s who went by the nickname of Perotto.

Lucrezia was to claim that the child she was carrying was Perotto’s and perhaps to protect her he concurred. If so his generosity of spirit was not rewarded as not long after his body was washed up on the banks of the River Tiber along with that of Lucrezia’s maid, both had been strangled and repeatedly stabbed.

The child once born became the notorious “Roman Infant” and the origins of the latest edition to the Borgia family were to remain shrouded in mystery. An official announcement from the Vatican declared the child to be Cesare’s by an unknown mistress but a Papal Bull never made public and discovered later declared the child to be Pope Alexander’s.

Could it be possible that a Pope fathered a child by his own daughter? The scandal would have rocked Christendom to its foundations and done much to destroy the credibility of the Catholic Church. Lucrezia perhaps provided a hint as to the real father when she named the child, Giovanni.

In July 1497, tragedy struck the Borgia family when the body of Lucrezia’s brother Juan was pulled from the River Tiber riddled with stab wounds. Juan had not just been Lucrezia’s favourite but also her father’s and had been showered with honours over and above the abler Cesare and known to be insanely jealous few doubted that he had murdered his own brother. Certainly, Lucrezia believed so and refused to remain silent on the issue. She was again sent away to a convent until she learned to control her grief.

But it wasn’t long before the old Borgia family loyalty once more prevailed and Lucrezia was permitted to return to Rome where Cesare took her under his wing, and she was rarely seen out except in his presence. She was even with him when he executed prisoners with a crossbow from the Vatican walls – it did little for her reputation.

Throughout her life Lucrezia Borgia was both admired and feared in equal measure. That she was beautiful by the fashionable standards of her day there could be little doubt. It was said that her golden hair fell beneath her knees, that her eyes were hazel but appeared to change depending on the light, that her complexion was clear and pale, and that she had a natural grace as if walking on air. A courtier Niccolo Cagnolo described her:

“She is of middle height and graceful of form; her face is rather long, as is her nose, her hair is golden, her eyes grey, her mouth rather large, the teeth brilliantly white, her bosom smooth, white, and admirably proportioned. Her whole being exudes gaiety and humour.”

But there was also a darker side to Lucrezia.

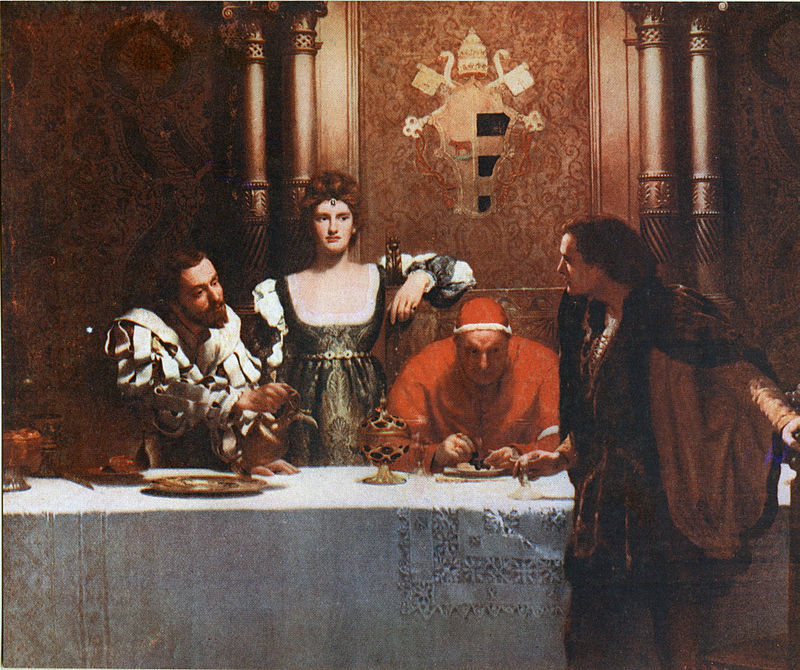

She regularly attended the dinners the Borgia’s were so fond of throwing which were often described as being little better than drunken orgies. She liked to organise them and would often greet the guests as they arrived. But a dinner invitation from the Borgia’s was not something to be taken lightly and for many it would be a last supper.

Lucrezia however was always the perfect hostess, nothing was ever too much trouble, and it was said that she was rarely seen without a smile. It was also said that she wore a ring that was hollowed out in the middle where was hidden a phial of poison. Whether this was true we do not know but it was certainly a rumour current at the time, and her presence at those dinner parties was to blacken her reputation for all time.

Lucezia’s devotion to her family was unquestionable and had she been ordered to kill there seems little doubt that she would have done so.

On 21 July 1498, Lucrezia married yet again this time to Alfonso of Aragon, Duke of Bisceglie, a strikingly handsome young man intelligent, sophisticated and charming. Even Cesare was impressed by his sister’s new husband, but this admiration soon changed to intense hatred when he discovered Lucrezia had fallen in love and his unnatural affection for his sister once again reared its ugly head.

As Lucrezia paid him less and less attention Cesare’s jealousy ate away at him like a cancer for he too had once been considered handsome in his youth, but his face had long since been scarred by sustained bouts of syphilis and he now wore only black in mourning for the loss of his good looks and even took on occasions to wearing a mask. Alfonso’s handsome features only deepened his enmity.

Aware of the peril he was now in Alfonso fled Rome but was persuaded by Lucrezia, who was six months pregnant with his child, to return.

On the night of 15 July 1500, Alfonso was attacked on the steps of St Peter’s, stabbed repeatedly and so badly beaten that he barely survived. Rescued by his attendants he was taken to his private chambers where Lucrezia and her sister-in-law Sancha remained at his bedside day and night. Slowly they nursed him back to health.

In the days that followed some of Alfonso’s men believing that Cesare was responsible for the attack on their master ambushed him in a crossbow attack, but the assassination attempt failed. A furious Cesare was determined to finish the matter and on 18 August he visited Alfonso in his bedchamber where he told him in a whisper: “What was not finished at breakfast will be completed by dinner.”

Later that same night Lucrezia and Sancha were lured away on a false errand and ushered into a room where Alfonso’s doctors were already being held. Left unattended and alone Alfonso was helpless as Michelotto, one of Cesare’s more brutal henchmen strangled him to death where he lay.

A hysterical and utterly distraught Lucrezia could neither be calmed nor placated and had to be sent away from Rome to live in the town of Nepi in the Etruscan Hills where though devastated by the murder of the man she loved she soon recovered enough to marry once more on 30 December 1501 to Alfonso d’Este, heir to the Dukedom of Ferrara.

Such was Lucrezia’s frightful reputation that the marriage proposal was initially declined but a dowry of 200,000 ducats and the threat of war served as persuasion enough.

Despite this unpromising start these were to be the happiest days of Lucrezia’s life. She had been full of trepidation about her reception in Ferrara, but her grace and charm soon won the people over. She had a lovely nature, they said.

In 1505, the old Duke Ercole died and Lucrezia became Duchess of Ferrara. She was a woman of substance and free at last of family interference.

Alfonso had little time for his wife and so Lucrezia busied herself in refurbishing the Royal Palace and cultivating court life. She surrounded herself with artists and poets including the painter Titian and also took a string of lovers one of whom, the courtier Ercole Strozzi, was murdered on the orders of her furious husband.

Lucrezia’s reputation in Ferrara survived her entanglement in yet another brutal murder and she was looked upon with affection as an able administrator, an impartial dispenser of justice and a generous patron of the arts.

The last few years of Lucrezia’s life were not so happy however, and she was to endure sustained bouts of depression. She had not aged well and for a woman who had always taken great care over her appearance this hurt her deeply and she was also prone to periods of reflection and regret.

She died unexpectedly on 24 June 1519; it was rumoured from complications arising from a botched abortion. She was just 39 years of age. Her death was much mourned in Ferrara but not elsewhere where it was said that it was God’s final judgement on a cursed family.

Lucrezia’s father Pope Alexander VI had died sixteen years earlier on 18 August 1503, after collapsing from a fever. The likelihood is he was poisoned. As he lay upon the ground writhing in agony and struggling to breathe his body was stripped of its robes and the rings torn from his fingers; and it was said he was so fat it was impossible to close the lid of his coffin.

Cesare who had been taken ill at the same time as his father only survived by immersing himself in a tub of ice-cold water. Now following the Pope’s death his power declined and he was arrested and imprisoned for two years only being released on condition he ceded his estates. Forced to flee to Spain he fought in the armies of his brother-in-law the Duke of Navarre where on 12 March 1507, he was ambushed, speared through the chest and killed.

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval, Women

Share this post: