Lusitania: Murder on the High Seas

Posted on 6th March 2021

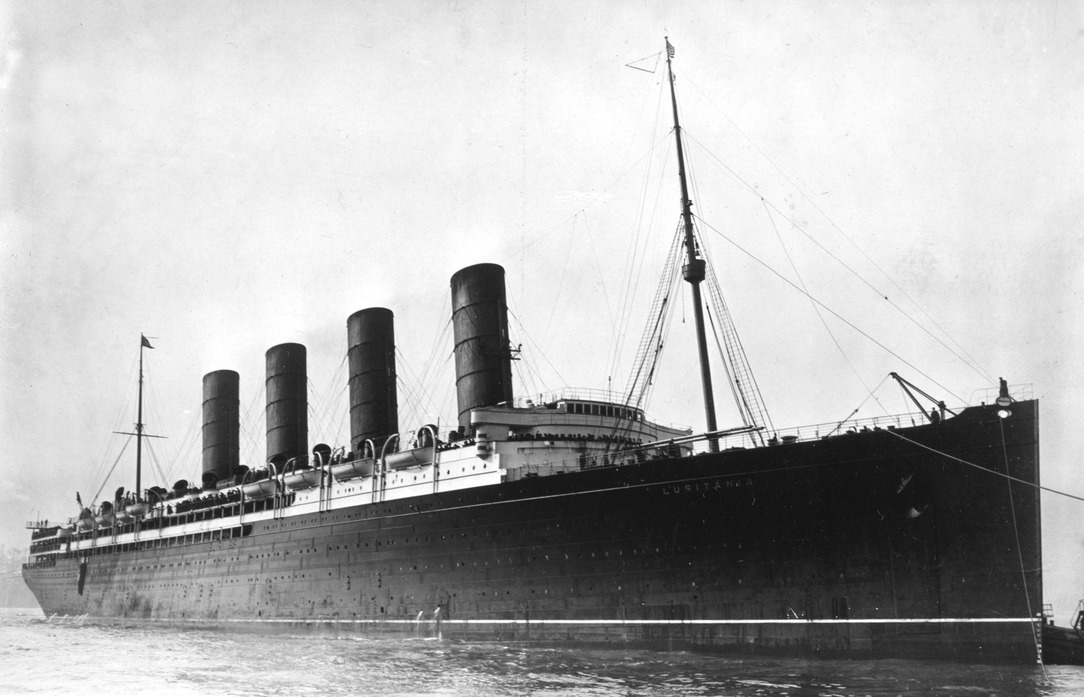

The RMS Lusitania known affectionately as the Lucy was considered by many to be the most beautiful and elegant ocean-going liner in the world. She had only made her maiden voyage as recently as 1907 and had since completed the trans-Atlantic crossing from Liverpool to New York more than 200 times. A previous Blue Riband winner she was sleek and fast and even in an age of elegance was seen to be something special.

All this seemed about to change when upon the outbreak of War in August 1914, she was appropriated for military service, stripped of her many adornments, had gun decks were fitted and she was reclassified as an Armed Merchant Cruiser. But the Admiralty doubting her effectiveness as a warship now had a change of heart deciding that she could better be used in her current capacity and so would continue much as before except that her cargo manifests would now include a great deal of war materiel. So, the guns were never fitted, and the luxury returned.

Since February 1915, following the German announcement of unrestricted submarine warfare, the trans-Atlantic journey to America and back had been one fraught with danger but the Lusitania was fast and capable of outrunning any submarine. She had also made the crossing many times before and had remained unscathed, there seemed no reason to believe that she could not continue to do so in the future.

On 27 April 1915 the Lusitania docked in New York and immediately began making preparations for the return journey.

Prior to the voyage her regular Captain, Daniel Dow, had been displaying signs of stress and was reluctant to continue in charge. Rather than wait for what seemed the inevitable resignation he was relieved of his command and Cunard appointed their most experienced Captain, William Turner to take command of their flagship vessel.

As Captain Turner familiarised himself with his new ship temporary crew members were hired and the cargo loaded.

On the ship's manifest were 4,200,000 rounds of ammunition, 1,250 empty shell cases, and 18 non-explosive fuses. At least that was the published manifest. It didn't seem a great deal in the context of the massive conflict that had gripped the European Continent and much of the rest of the world, but it was enough for the Germans to declare it contraband of war.

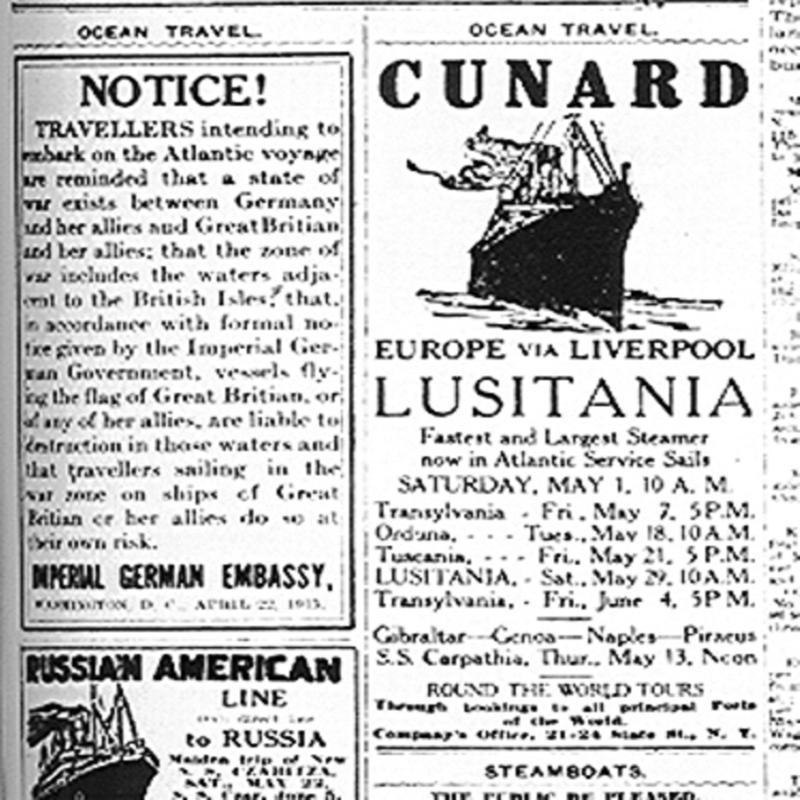

Several passengers concerned that the cargo would make the Lusitania a target for submarines now approached the German Embassy for clarification and as a result, the Embassy issued a notice that would appear beneath posters advertising the Lusitania's return journey. It read:

"Travellers intending to embark on the Atlantic voyage are reminded that a state of war exists between Germany and Great Britain and that the zone of war includes the waters adjacent to the British Isles, in accordance with formal notice given by the German Imperial Government vessels flying the flag of Great Britain are liable to destruction in those waters and travellers sailing in those waters do so at their own risk."

The warning did have the effect of frightening some passengers who sought out Captain Turner to express their fears. He reassured them that the Lusitania was too fast to be caught by any submarine and when they saw the magnificence of the ship it didn't seem possible that it could be sunk by a torpedo. For others the element of danger simply added to the excitement, and so when the Lusitania sailed from New York Harbour on 1 May 1915, it was with a full complement of passengers and crew.

The first few days of the Lusitania's voyage were trouble free and in the calm water of mid-Atlantic the war seemed elsewhere and far away; but there was hardly a passenger aboard who wasn't aware that they had not yet reached the so-called killing zone.

Captain Turner had decided to ignore Admiralty advice and adopt a zig-zag course instead would rely upon his instincts as an experienced mariner.

Speed, he believed, was the best strategy for a safe journey and as the Lusitania approached Ireland, he also decided to hug the coastline, even though this was known to be the preferred hunting ground of the U-Boat and as the Lusitania neared the British Isles the mood aboard the ship changed. People were nervous and excited in equal measure.

Passengers lined the decks to see if they could spy a periscope in the distance or see that tell-tale streak of foam that indicated an approaching torpedo.

On 6 May, Captain Turner received the message: "Submarines active off the south-coast of Ireland." He immediately took all necessary precautions - the lights were extinguished, all water-tight doors were closed, extra lookouts posted, and the lifeboats swung out on their davits.

But despite all this Captain Turner still refused to adopt a zig-zag course and the Lusitania continued to sail in a straight line and having earlier encountered a light mist even reduced speed to 18 knots. She was for the time being at least a sitting target.

At 1.20 pm on 7 May, as the Lusitania passed the Old Head of Kinsale, U.20 under the command of Captain Walther Schwieger surfaced to recharge its batteries. Scanning the horizon, he could see through his binoculars one of the largest Ocean Liners then in service and could barely believe his luck but he was also aware that he only had two torpedoes remaining. U-20 quickly submerged while Captain Schwieger pondered what to do.

He was aware that the Liner would have women and children aboard, but he had sunk Liners before without loss of life, but then he had allowed the passengers and crew to abandon ship first.

This would not be doing so on this occasion for h could see clearly the gun fittings and was aware that Liners had been ordered to attempt to ram any U-Boat it saw on the surface.

At 2.10 pm Captain Schwieger let loose one torpedo.

His decision to do so was the cause of friction among the crew, one of whom Charles Voegele refused to participate in an attack upon women and children a decision for which he was later to spend time in prison.

On the Lusitania a lookout saw the approaching torpedo and shouted the warning:

"Torpedo coming on the starboard side!"

But the warning had come too late to take effective evasive action and just 70 seconds after it was launched the torpedo struck. The explosion rocked the ship but a single torpedo should never have been enough to sink the Lusitania, but it was soon followed by another much larger secondary explosion and it was this that doomed the ship.

The Lusitania soon began to list severely, and it quickly became evident to Captain Turner that he could not keep the Lusitania afloat but she was also within sight of land. He immediately steered a course towards the Irish coast and ordered full steam ahead in the hope of beaching her. In the meantime, he also gave the order to abandon ship.

Charlotte Pye was a young mother from Canada who was travelling to Britain to visit her parents and was eating lunch in the dining room with her eighteen-month-old daughter Marjorie. She had been telling another passenger how she intended to stay on deck for the remainder of the voyage as she feared the ship would be attacked. The other woman sitting across the table from Charlotte scoffed at the suggestion and had just told her that that the Germans would never do such a thing when the torpedo struck.

Charlotte remembered how it felt as if the bottom of the ship had been torn from under them and how people began screaming – She’s going down! She picked up Marjorie and rushed to the boat deck, but it was a struggle and ship’s list was so severe that she could barely stand up let alone walk. She was also in a panic because she did not have a lifebelt but one of the male passengers removed his own and attached it to Charlotte.

Some people believe this man to have been the multi-millionaire playboy and sportsman Alfred Vanderbilt who was later reported by witnesses to have been seen doing so.

Charlotte then managed to get Marjorie lifted into a lifeboat and quickly followed her.

As the lifeboat was being lowered into the water however the Lusitania began to lurch onto its side and it seemed as if it was about to fall onto the lifeboat and in the ensuing panic aboard it capsized throwing Charlotte, still desperately clinging onto Marjorie into the water.

Holding onto her daughter Charlotte could not swim away from the ship and as it began to sink, she was pulled under the water by the suction the force of which was so great that it ripped Marjorie from her grasp. Charlotte was later rescued from the water suffering from hypothermia, but she was never to see her daughter alive again.

Marjorie’s little body was later recovered and buried in Queenstown along with so many others.

On board the Lusitania there was chaos and panic soon began to spread particularly when the electricity failed, and lights went out plunging the ship into darkness. Some people now found themselves trapped in the electric elevators in between decks and could not get out.

Others who could barely see groped in desperation for the stairwells that could lead them to safety. The loss of power also meant that the water-tight doors that had been closed earlier as a precaution could not now be reopened trapping the men inside.

By now the ship was listing so severely that people could barely remain upright, and the speed of the ship made it impossible to launch the lifeboats safely and many were smashed against the ship’s side throwing those inside around like rag dolls. Others overturned tipping the people into the swirling sea below, and of the 48 lifeboats aboard the Lusitania only 6 were launched successfully.

Just 18 minutes after the torpedo struck the Lusitania went to the bottom taking 1,198 of the 1,959 people aboard many of whom never escaped the bowels of the ship with her.

Among those who drowned were 128 American citizens many of them prominent people who appeared regularly in the society columns along with three German nationals who had been imprisoned in ships brig for security reasons and a British teacher suspected of being a German spy.

The Lusitania had been sunk within sight of land and the rescue operation had begun almost before the first distress signal had been received. Naval vessels were ordered to the scene but the nearest was still more than two hours sailing distance away and so Tugs and fishing vessels from the nearby port of Queenstown now rushed to the scene but even these were to take 45 minutes to arrive and for many of the hundreds of survivors thrashing about in the bitterly cold water it was too long.

Captain Turner survived the sinking of his ship when he was swept off the bridge as she went down only to be plucked unconscious from the sea some three hours later.

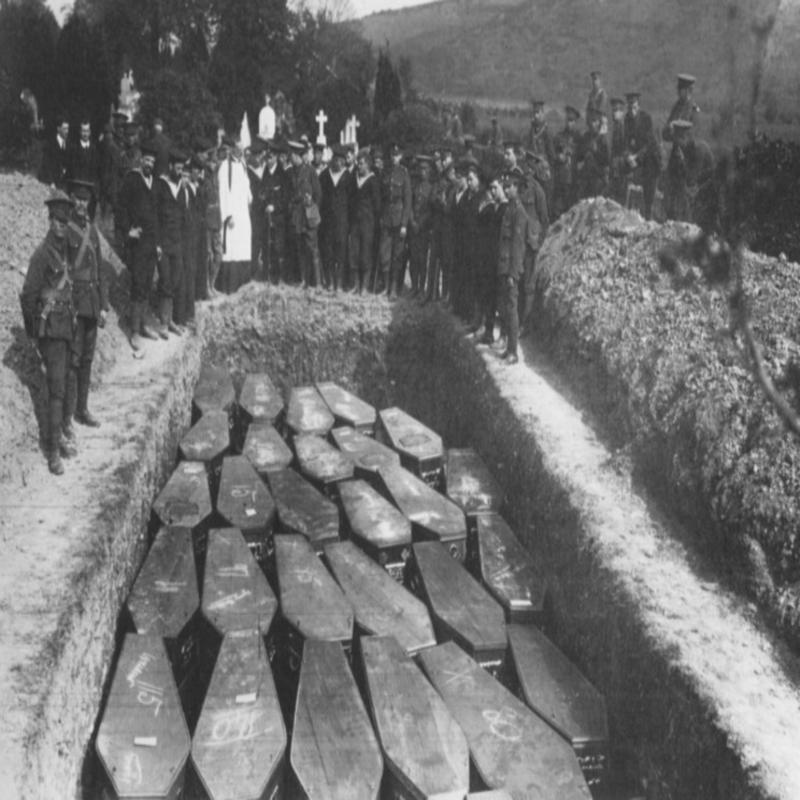

The Cunard Line offered a cash reward to local fisherman for each body recovered from the sea but only 289 ever were of whom 65 were never identified.

The dead, some of whom were mothers with their babies still strapped to their bodies, were laid out for identification before later being buried with two children to a coffin in mass graves in Queenstown.

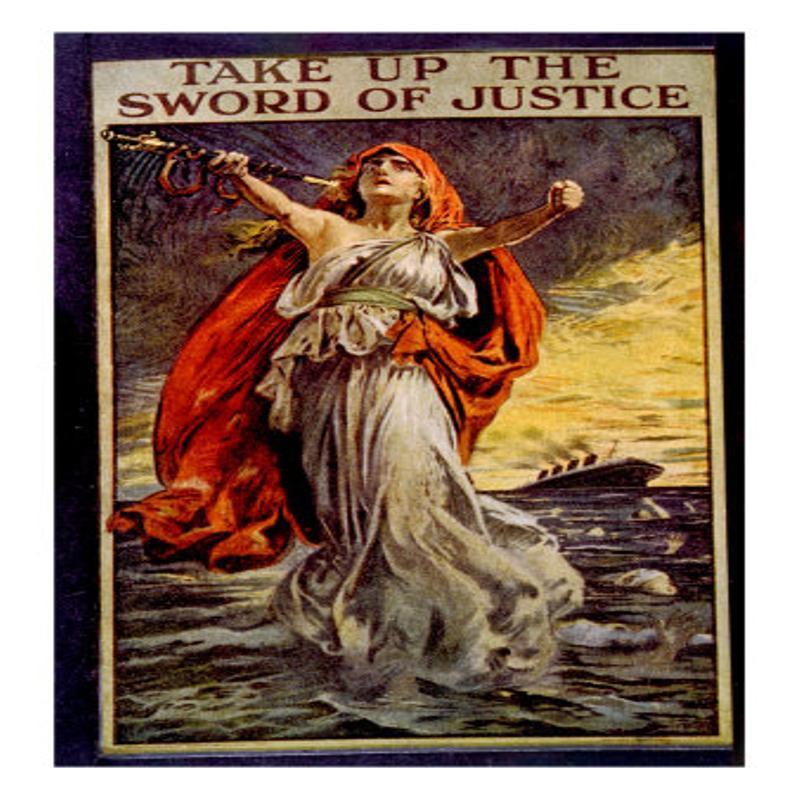

The sinking of the Lusitania had been a terrible tragedy, but it was also a great propaganda coup for the Allies and the British Government were quick to use the incident to create considerable anti-German feeling in the United States painting the Germans as a monstrous race beyond the pale of civilised behaviour – they were the Beastly Hun.

President Woodrow Wilson was never going to take his country to war over the sinking of the Lusitania, but the pressure was such that he felt obliged to protest to the German Government in the strongest possible terms.

The Germans, fearing American intervention in the war temporarily abandoned its policy of unrestricted submarine warfare which it did not resume until February 1917. So successful was the policy upon its resumption it in cutting trans-Atlantic lifeline that Britain was to come to within four weeks of starvation. Had Germany persisted in its policy of unrestrictive submarine warfare following the sinking of the Lusitania she may well have forced Britain out of the war.

In Berlin Captain Schwieger was lauded as a hero.

He knew well the consequences of his actions and it was not a view he necessarily shared but then the Lusitania was perceived to have been nothing less than a gunrunner. If women and children had died, then it was the fault of the British Government for either recklessly putting their lives at risk or deliberately using them as human shields.

A medal was struck to celebrate the sinking - on one side was the image of Captain Schwieger and on the other the crippled Lusitania with the words No contraband!

The German Governments initial response to the sinking went some way to easing Schwieiger’s conscience and he looked forward to the promotion that would assuredly follow but the universal condemnation of his actions elsewhere was to see the German Foreign Office backtrack and adopt a more apologetic approach. Schweieger was quietly side-lined.

The British Government also obtained some of the medals and reproduced them in their thousands which they despatched around the world reinforcing the view that the Germans were an evil, amoral people who did not share the values of civilised society.

Was the Lusitania then a legitimate target?

The official Board of Trade Inquiry into the disaster presided over by Lord Mersey concluded that the Lusitania had been sunk by a single torpedo with no secondary explosion in an act of callous pre-meditated murder. Captain Turner was deemed negligent in not following to the letter Admiralty instructions but was cleared of any blame for Lusitania’s loss.

Wartime restrictions meant that many of those who gave evidence at the Inquiry including Captain Turner, were unable to reveal the full facts of what they knew and witnessed and there is little doubt that the Admiralty applied pressure to ensure that this was so.

Lord Mersey was later to say that the Lusitania Inquiry had been a “damn dirty business” and his final report has never been published.

Captain Walther Schwieger, who went from hero to villain and then to conveniently forgotten was killed on 5 September 1917 when the U-Boat he was commanding struck a mine was and was sunk with all hands.

Share this post: