Madame Caillaux: A Crime of Passion

Posted on 18th May 2022

In the summer of 1914, as the peoples of Europe basked in bright sunshine and temperatures soared storm clouds were forming overhead. The Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Habsburg Imperial Throne had been assassinated in Sarajevo, the repercussions of which were yet to be fully realised. There were many in Vienna and elsewhere outraged and eager to punish those responsible while in London and Berlin diplomats were hard at work attempting to douse the flames of reprisal. In France however, which would be on the front-line of any European conflict, the very real prospect of war barely received newsprint for they were distracted by scandal, what some were calling the crime of the century.

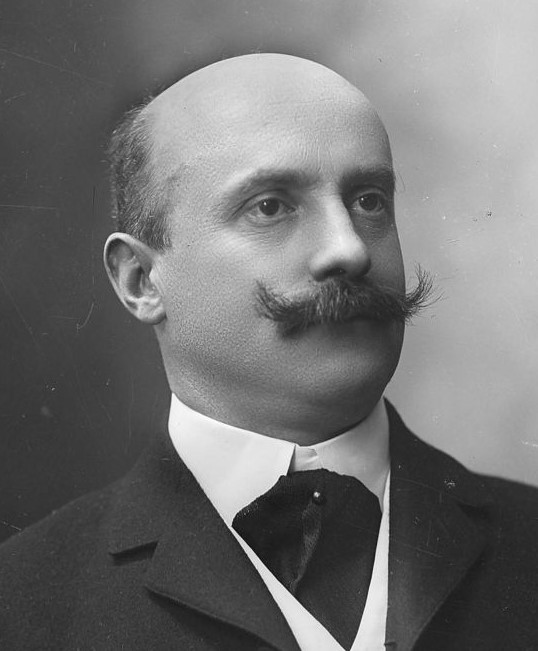

Henriette Caillaux, a 40-year-old socialite married to the former French Prime Minister Joseph Caillaux was on trial for the murder of the Editor of Le Figaro Gaston Calmette, a severe critic of her husband who had accused the then Finance Minister of not just corruption but sexual impropriety.

Henriette was furious that Calmette, had broken with the journalistic etiquette of the time to publish private letters intended to harm her husband’s reputation, letters that portrayed him as a man insincere, duplicitous, and of low cunning. She also feared he had in his possession further private correspondence of her husband’s that showed she and Joseph had an adulterous affair before they were married - she’d heard rumours to that effect and dreaded the prospect of a scandal that could be the ruin of them both. Her worse fears appeared, confirmed when on 13 March Calmette published an intimate letter written by Joseph a dozen years earlier to Berthe Gueydan, his then mistress who would soon become his first wife.

It was clear that the Editor of Le Figaro was not prepared to adhere even to those standards set by himself when it came to reporting on the radical Caillaux, who he accused of being both a pacifist and a suspiciously close friend to Germany.

The attacks upon him, often venomous, were organised by his rivals in the Chamber of Deputies and their mouthpiece was the pages of Le Figaro. Caillaux, a veteran politician who gave as good as he got expected no less and did not take the insults personally – Henriette did, however.

She demanded that Joseph challenge Calmette to a duel, it was a matter of honour she said. But this he refused to do, duelling was illegal and though a successful outcome might restore his honour it would destroy his political career. She chastised her husband for his timidity and determined that if he would do nothing then she would take matters into her own hands – she at least was no coward!

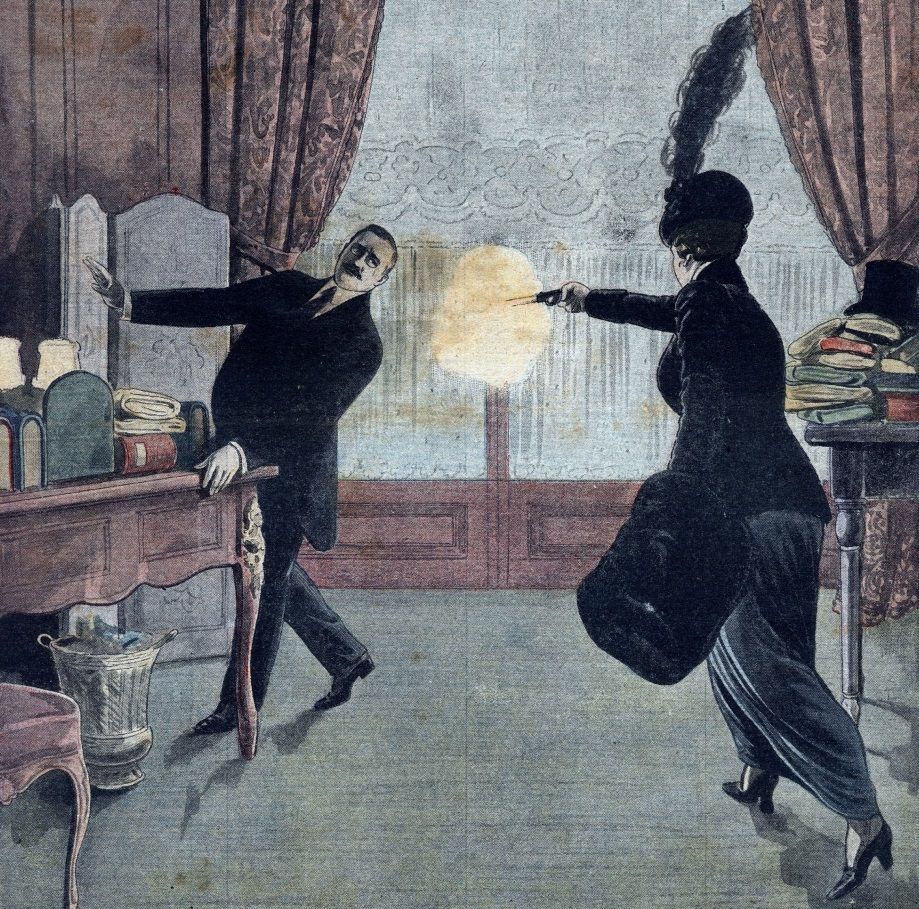

On the afternoon of 14 March 1914, she visited the Paris office of Le Figaro and demanded to see its Editor. When she was informed that he was out but would return soon she decided to wait and not bothering to remove either her coat or fur muff she took a seat where she remained for over an hour saying nothing and just staring blankly into space.

Calmette returned just after 6 pm in the company of the novelist Paul Bourget with whom he intended to dine. Notified of Henriette’s presence by his assistant Adrien Cirac, much to his friends surprise he agreed to meet with her declaring “It’s a woman, I cannot refuse to see a woman.” Cirac invited Henriette into Clamette’s office and closed the door. Bourget remained outside.

Henriette was then heard to say, “You know why I have come?” To which Calmette replied, “Not at all, Madame.” There was then a brief but more heated exchange of words before Henriette removed a Browning pistol from her muff and firing at point blank range emptied the entire chamber, two bullets missed but the other four buried themselves deep into Calmette’s abdomen. The noise alerted others in the building who rushed to the scene; Cirac was the first to arrive, he saw Henriette standing over the still alive but barely conscious Calmette the smoking gun in her hand. He quickly summoned a doctor while Henriette made no attempt to flee but instead calmly awaited the arrival of the police who arrested her at the scene. She denied nothing declaring that “since there is no more justice in France, I resolved that I alone would be able to put a stop to his campaign.” But she refused to accompany them in a police van. She would only travel in her chauffeur driven car that was waiting outside - the police agreed to her request.

Six hours after he was shot Gaston Calmette died of his wounds and the police charged Henriette Caillaux with his murder. If convicted, she could face the death penalty.

Henriette was taken to Saint Lazare Women’s Prison where she was provided with a private heated cell and attended upon by both her maid and her hairdresser. She was also permitted to dine with her husband in the Prison Governor’s office. Such privileges were hardly commonplace and when revealed caused a great commotion.

The case dominated the front pages of every newspaper in France for months and the press took sides of course, the left-leaning papers Le Matin, Le Petit Parisien and Le Petit Journal were largely sympathetic towards who they portrayed as a ‘wronged’ woman while Le Figaro understandably more hostile.

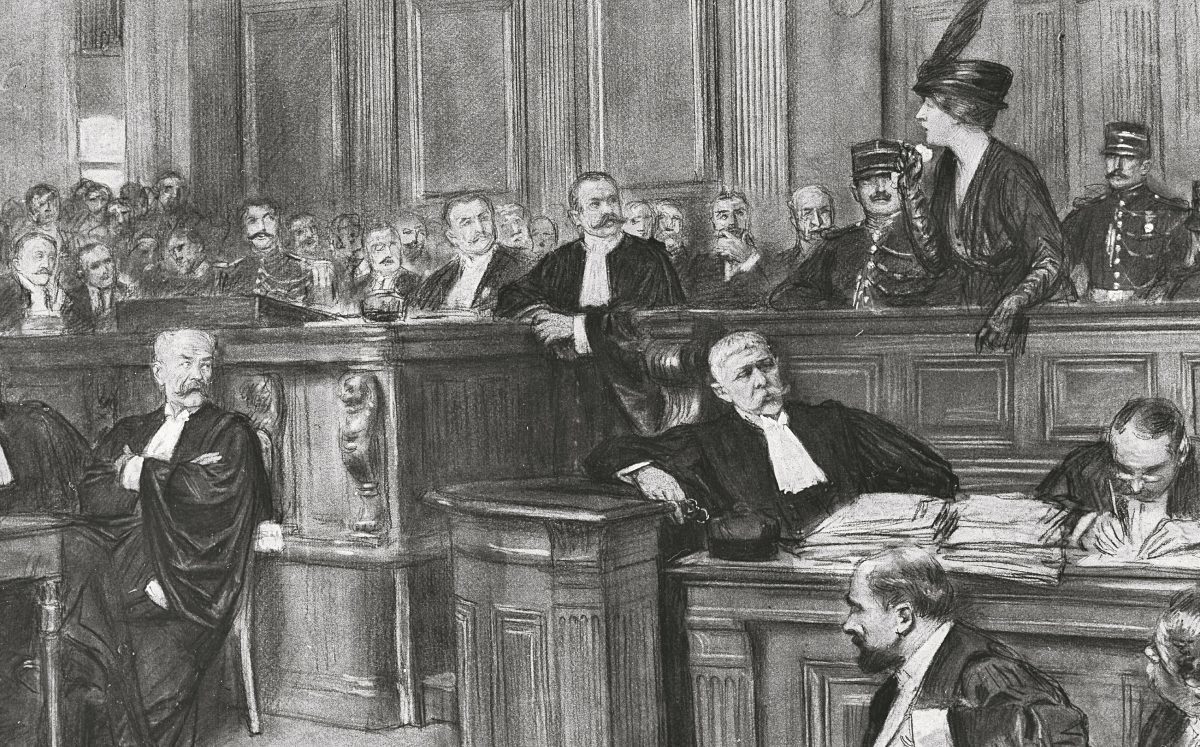

By the time the trial opened on 20 July, the nation was transfixed. The Defence Counsel was led by Fernand Labori, one of France’s leading advocates, a celebrity lawyer who had previously defended both Alfred Dreyfus and the novelist Emile Zola, a man who knew well how to further sensationalise an already sensational case. The Prosecutions lead lawyer was Charles Cheru an experienced and much respected lawyer. He and Labori had clashed many times before and he was aware of his rival’s ability, but it shouldn’t be too difficult for a man of his legal expertise to prove what should to all intents-and-purposes be an open and shut case. He merely had to stick to the facts, or so it seemed.

The trial lasted nine days and the packed press gallery reported every moment with bated breath and in great detail, the protagonists, the witnesses, the testimony. They described how Henriette would faint dramatically at moments of duress and how her husband Joseph “rushed, leapt, and ascended the railing to take his wife in his arms.”

The Prosecution painted her as a cold and calculating woman whose haughty manner in the dock betrayed her true self not the contrived hysterics she engaged in from time to time merely to garner sympathy. They made a great deal of her remark that on the day of the murder, “I did not yet know if I would be going to tea or to Le Figaro,” as if cold blooded murder was barely distinguishable from an hour or two of fine dining.

The Counsel for the Defence was in no doubt that Henriette Caillaux was the victim not the man who brought his death upon himself. She was every inch the dignified lady of leisure but a woman nonetheless who was vulnerable to that emotional instability that infects every woman. Her weak frail nature was incapable of being able to cope with scandal, the torment of public exposure. If she showed no remorse for what she had done it was because she did not understand what she had done.

On the sixth day of the trial she took to the witness stand. As she entered the Court that morning she was described as, “more pale than ever and already giving signs of extreme distress. Making an almost superhuman effort not to give vent to her feelings and scream. Overcome with emotion she fainted.” It was later

described by Le Parisien as “an attack of nerves.”

On the Witness Stand she played outrageously to the jury and the gallery just as her Counsel had instructed her to. She was a pitiful, emotionally unstable creature, difficult to understand and impossible to predict. She was utterly incapable of controlling her more extreme emotions what Labori would call in his summing up as her “unbridled female passions.” He also made use of the new science of psychology, of the unconscious and the unfathomable. Poor Cheru for the Prosecution had no answer, he could only relate the facts of the case which should have stood for itself, but the trial had long since ceased to be about facts and was by now all about feelings.

The trial had lasted 9 days but the all-male Jury took just an hour to reach a verdict of not guilty. They declared her murder of Gaston Calmette a crime of passion, it astonished all who heard it and there was a stampede as the many reporters present dashed out of the Court desperate to be the first with the story.

It was 28 July,1914, and in less than a week the trial that had captivated a nation would be forgotten, France would be at war.

Share this post: