Madame Roland: O Liberty!

Posted on 3rd September 2021

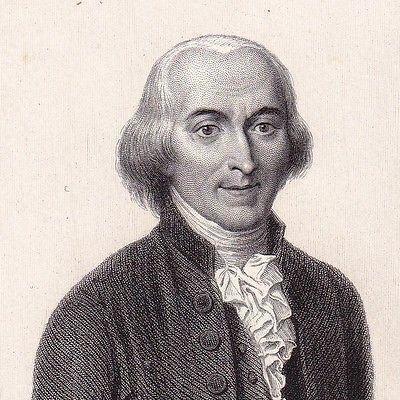

Madame Roland was perhaps the most influential woman to emerge from the French Revolution at a time when women were not expected to wield any influence at all, especially not in the arena of public affairs. The fact that she did so at a time of political uncertainty and revolutionary upheaval made her all the more extraordinary but then she was a particularly strong-willed and single-minded woman and one blessed with the indefinable gift of persuasion.

She was born Marie-Jeanne Phlippon on 17 March 1754, in Paris as the only one of seven children to survive into infancy. Her father, Pierre, was a master-engraver who lived above his shop.

Though they were by no means poor her father had to toil long hours in his workshop to ensure that their standard of living was maintained and in his absence Marie’s mother, Marguerite, described as a sweet and reasonable woman presided over a remarkable education for her daughter and the Young Marie, an avid reader was eager to learn, her mother more than happy to indulge her.

Before she reached maturity, she was already fluent in Italian and English, could read and write Latin, and was an accomplished dancer and musician.

She later became a devotee of Voltaire and Rousseau whom she credited with making her a devoted Republican, though not an uncritical one, and she was to describe herself as a woman of the Enlightenment. She was also for a time deeply religious and expressed an interest in becoming a nun but a year’s sabbatical in a convent soon disabused her of that notion. To be compliant even to God was not in her nature.

Her father was impressed and proud of his only child and resented the lack of opportunities that were available to his brilliant little girl, outside of a good marriage that is. She was to achieve that end at least when in 1781 she married Jean-Marie Roland, a man twenty years her senior who was the Inspector of Manufactures for the region of Picardy and they soon settled in Lyon where Marie gave birth to a daughter.

Described as attractive rather than beautiful, often argumentative, and as someone who worked tirelessly on her husband’s behalf despite an often-tempestuous relationship she was never afraid to express an opinion and had strong political views as those who met soon discovered. But even in the cauldron of political debate she always remained calm and rarely raised her voice, a character trait that some found disarming.

She was to prove a great asset to her husband whose career flourished largely as a result of Marie’s ability to communicate and build up a formidable network of influential people who were happy to call her a friend. By the late 1780’s the couple were resident in Paris and Marie regularly attended meetings of the recently formed Jacobin Club.

Believing that the State should exist for the benefit of all its citizens she was excited by the revolution that followed the fall of the Bastille on 14 July 1789, and was eager to see what she considered to be her ideas put into practice.

She was determined that her husband should enter politics and networked furiously to guarantee his election to the French National Assembly. Her hard work paid off when in November 1790, Jean-Marie Roland was elected the representative for the city of Lyon.

Despite being a familiar figure at the Jacobin Club, Marie rarely spoke, perhaps acknowledging her status as one of the few women present so in 1791, she opened her own Salon for political debate at the Hotel Britannique where leading lights of the Revolution such as Mirabeau, Danton, Brissot and Robespierre were regular visitors. Here she held court, spoke her mind, and never shied away from delivering advice or indeed a dressing down to those who opposed her views, and few doubted for a moment that whenever her husband addressed the National Assembly it was her words he spoke.

In 1792, the Roland’s shocked many of their close associates when they abandoned the Jacobin cause and embraced the more moderate Girondin faction in the National Convention. It was to prove an error of judgement but in the short-term they were rewarded when the Girondin leader Jacques-Pierre Brissot, with the consent of the King, appointed Monsieur Roland to the post of Minister of the Interior and it was not long before Madame Roland, as she was by now commonly known, began involving herself in her husband’s work.

More radical than he was she was also to prove more impassioned and less temperate in her use of language also. She had long been penning his letters for him and now started issuing instructions on his behalf. She had even written to the King under her husband’s name demanding that he either embrace the Revolution or face the consequences: “I know that the stern language of truth is rarely welcomed by the throne, I know too that it is because truth is almost never heard that revolutions become necessary.”

But in the febrile atmosphere of Revolutionary France, she was making enemies and her ever growing number of detractors were vocal in expressing their anger that she, a woman, who held no official position, should wield such power and to many she became known as that – Damnable Woman! It was to cost her husband his job and put their future safety in jeopardy.

Encouraged by his wife Monsieur Roland who was the man charged with the responsibility for rooting out Royalist sympathisers, counter-revolutionaries, hoarders, and speculators now railed against the excesses of the Revolution in the National Assembly but this was not what the mob on the streets of Paris wanted or expected – they demanded action, they wanted heads to roll.

Rumours began to spread that the Roland’s themselves had Royalist or counter-revolutionary sympathies and it wasn’t long before these rumours became out-and-out accusations.

Fearing the worst, Madame Roland felt obliged to address the National Convention in person and so before a largely hostile audience but remaining calm and self-assured she put up an eloquent, sometimes humorous, but always spirited defence of both herself and her husband.

The accusations she dismissed as being without foundation, they were just nonsense, so much hot air. The Assembly rose as one in applause, and both she and her husband were acquitted in the minds of those present of any imagined charges that may have been pending.

But the National Assembly was not sitting as a Court of Law nor was it the Revolutionary Tribunal and they had already been found guilty in the Court of Public Opinion - it was only a matter of time.

On 31 May 1793, a Jacobin inspired coup ousted the Girondins from power and the following day their leading members, among them the Roland’s, were arrested. Separated Jean-Marie and Marie-Jeanne Roland were never to see one another again.

Confined in the notorious Saint-Pelagie Prison she was made to endure an interrogation of such unrelenting hostility that she could have been left in little doubt as to her fate. She was treated with greater respect once removed to the Conciergerie to await trial, surprisingly so given the treason charge that now hung over her.

She was allowed frequent visitors and even writing materials which despite having previously said that she would rather chew off her fingers than be a writer, she used to pen her memoirs.

It seemed for a brief moment that her previous friendship with Maximilien Robespierre and the other leading Jacobins might save her, but it soon became evident that this would not be. Still, she remained incorrigible and while in prison it was said she managed to manufacture her husband’s escape from his.

But despite her courage, and the frequent tears tinged with recrimination, she knew there was no hope for her. Prior to her trial before the Revolutionary Tribunal, she urged her lawyer Chavieu not to attend fearing for his safety if he did so telling him: “Do not come tomorrow, you will endanger yourself without saving me. Accept this ring as a token of my gratitude. Tomorrow I will cease to exist.”

On 10 November 1793, she was taken before the Revolutionary Tribunal and harangued without let up. On the rare occasion she tried to speak in her defence she was shouted down by those of the Paris mob who had been permitted to attend. In the end she simply confessed to the accusations made against her and admitted to being proud of her association with the Girondins and insisting that both she and her husband had only ever worked to preserve the Constitution but when it was demanded of her that she reveal her husband’s whereabouts she replied: “I do not know of any law by which I can be obliged to violate the strongest feelings of nature.”

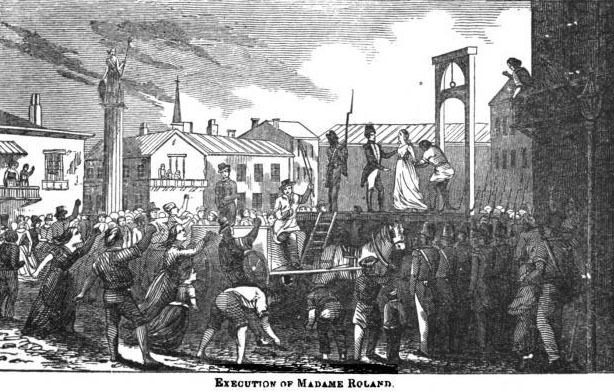

Following this the Tribunal rushed to judgement finding her guilty of treason and condemning her to death the sentence to be carried out later that day. In response to the verdict, she said: “I thank you, gentlemen, for thinking me worthy of sharing the fate of the great men you have previously assassinated. I shall endeavour to imitate their firmness on the scaffold.”

Just a few hours later she was taken from her cell on what was a cold, grey and overcast day for the short journey to the Place de la Revolution which had long since become a place of public entertainment not just of execution, and the mob was in full voice.

Long resigned to her fate she remained un-cowed by the jeers and the violence of the abuse levelled at her as never a Godless Republican she prayed to the Almighty into whose hands she would soon be delivered.

Before placing her head on the block beneath the blade that would kill her, she turned towards the image of liberty and bowing before it uttered the words for which she is now famous: “O Liberty! What crimes are committed in thy name!”

Two days later upon hearing the news of his wife’s execution Monsieur Roland who had been trying to flee the country sat down beneath a tree and scribbled out a quick note in a faltering hand: “From the moment that I learned they had murdered my wife, I can no longer remain in a world stained with such enemies.” He then pinned the note to his chest before running himself through with a sword.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous, Women

Share this post: