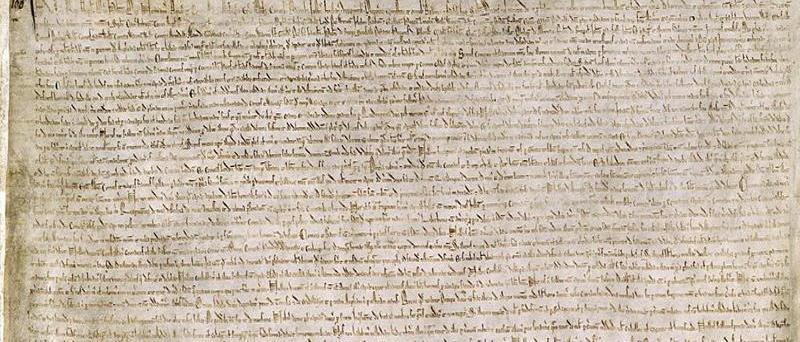

Magna Carta Liberatum

Posted on 4th January 2021

Most great change comes about as the result of conflict of one sort or another and never is this more so than in the realm of politics and subsequent alterations in the balance of power. Now and again such change creates a legacy that goes far beyond its original intent and indeed the imagination of its protagonists - the meeting between King John I and his Barons on the field of Runnymede on 15 June 1215, and the document it produced is one of those moments.

Few reigns have been as chaotic as that of King John, Plantagenet, and scion of the powerful Angevin Dynasty. He was the fifth son of the wily Henry II, and his strong-minded and independent Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine. Sadly, he lacked all their qualities other than it seemed the one for making enemies.

John Lackland as he was to become known, was crowned King of England on 6 April 1199, but it had not been an uncontested coronation and so to impose his authority in 1203 he waged war against those who advocated the claim of his 15-year-old nephew, Arthur of Brittany. His campaign was only a partial success at best but during it he had taken possession of Arthur and following an argument during which the young boy had insulted him to his face John had him murdered.

John was to equate his murder of a child with the reassertion of his authority and flushed with success now refused to pay homage to his titular overlord Philip Augustus of France, but he soon proved himself no General and in the war that followed he was to lose the provinces of Maine, Anjou, and most of Poitou.

To those of the Barons who had served under his brother Richard the Lionheart it was a costly and unprecedented humiliation but determined to regain his lost territories and restore his prestige John continued to wage war and the taxes raised to pay for it soared, an imposition acceptable to those required to pay it only if the plunder that comes from military success compensates and more. But there were few victories and John was soon being mockingly referred to as ‘Soft Sword.'

In 1207, he argued with Pope Innocent III over the latter’s choice of Stephen Langton as Archbishop of Canterbury, and his refusal to compromise on the issue saw him not only excommunicated but England placed under Papal Interdiction wherefore there would be no further communion, no more confession or absolution, marriages no longer received Church sanction, christenings were no longer performed, and the dead were buried in un-consecrated ground.

John responded by seizing Church property and filling his coffers with illicit treasure which brought little comfort to those who now feared for their immortal souls. But it was yet another war that he was destined to lose.

In January 1213, Pope Innocent pronounced sentence of deposition on John authorising Philip Augustus to wage Holy War on England and in May, under threat of invasion, with the country close to financial ruin and descending into chaos, John paid homage to the Pope as his Feudal Lord effectively handing England over to Papal control.

Not long after his humiliation at the hands of the Pope, John once again went on campaign in France and with the same disastrous results as before. Routed at the Battle of Bouvines he lost most of what remained of his possessions in France. For many of his Barons tired of the burden of taxation, the lack of respect for their rank, the trampling of their feudal rights, and the arbitrary expropriation of their property it was the final straw and on 14 January 1215, the rebel Barons along with leading members of the clergy led by Archbishop of Canterbury Stephen Langton confronted the King in London.

The Barons arrived not only with their demands but in full armour to which John took offence and so refused to negotiate with them, though he did with Stephen Langton granting the Church a separate Charter. But in all other matters he remained intransigent, and the talks broke up with harsh words and in ill-temper.

The last best chance of a settlement had been lost and the rebel Barons departed to their estates in high dudgeon and prepared for war. In the meantime, John had recalled William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke, from the exile into which he had earlier sent him to rally those Barons still loyal.

Still physically imposing and vigorous despite being almost 70 years of age William Marshal was renowned for his courage, his honesty, and his integrity. Indeed, he was the very epitome of chivalry and with the respect even of his enemies Marshal was the only man John could conceivably turn to. But for the time being at least there was little he could do.

When the opposing sides met on the Field of Runnymede on 15 June 1215, it was as two armed camps with battle seeming as likely as compromise but then John, not for the first time in his life, having gathered his forces declined to fight. Ever mistrustful, even of those who had proffered their support and had turned up armed in his defence he decided on this occasion discretion to be the better part of valour and would unlike six months earlier in London negotiate a Barons Charter.

For four days John would listen to a litany of complaints often in bad temper sometimes in sullen silence but rarely with any sincerity. It was after all just another Charter, and such Charters were commonplace in Medieval Europe - but this one would be different. Although most of its articles Clauses deal with feudal rights, ostensibly the property rights of a privileged few, the Free Men referred to in the preamble for the first time saw an anointed King answerable only to God also be made subject to the law of the land.

Article 39 and 40 (The Justice Clause)

No free man shall be seized or imprisoned or stripped of his rights or possessions or outlawed or exiled or deprived of his standing in any way nor will we proceed with force against him or send others to do so except by the lawful judgement of his equals or by the laws of the land.

It continued:

To no one will we sell, to no one deny or delay right of justice.

The Justice Clause is the most famous and the most often quoted of Magna Carta’s 62 Articles and has evolved to form not only the basis for the legal systems of liberal democracies around the world but also the judicial reference point for regimes in which the dispensation of justice is not entirely devolved from the practice of political power.

Articles 12 to 14 (The Taxation Clause)

No scutage or aid (tax) may be levied within our Kingdom without its general consent.

The King could no longer impose taxation upon his subjects without making provision for the calling of the (Barons) Council and the agreement of that Council. This would later be understood to mean Parliament.

The Taxation Clause of Magna Carta would be used to oppose the imposition of taxes by Charles I during the suspension of Parliament and the period of his personal rule. It would also serve as the inspiration for the rallying cry of the American colonists of No Taxation without Representation during the War of Independence.

Articles 60 and 61(The Security Clause)

Since we have granted all these things for God, for the better ordering of Our Kingdom, and to allay the discord that has arisen between us and our Barons, and since we desire that they shall be enjoyed in their entirety, with lasting strength, forever, we give and grant to the Barons the following security: That they (The Barons) shall elect twenty five of their number to keep, and cause to be observed with all their might, the peace and liberties granted and confirmed to them by the Charter.

Also contained within it was the proviso that:

The King shall seek to obtain nothing from anyone, in our person or through someone else, whereby any of these grants or liberties may be revoked or diminished.

For the first time restraints were imposed upon the Royal power and the prerogatives of the King. If he failed to abide by the terms of the Charter after notice had been given of his failure to do so by at least 4 of the 25 Barons on the Council, and if any non-compliance continued thereafter, then the Barons would be absolved of their Oath of Fealty and could take up arms against him. It meant the King was no longer the sole power in the land and the Security Clause would provide the principle upon which Parliament would oppose the Stuart Monarchy and Charles I’s claim to rule by Divine Right.

In the meantime, John was derided on the Continent for becoming a King who was subject to his subjects.

King John at Runnymede had little choice but to concede the Barons Charter, but he did so reluctantly and in bad grace refusing to put his name to the document or even use the Royal Seal in person. He also had no intention of abiding by it.

The meeting broke up on 19 June following the taking of Oaths with the Charter immediately reproduced and widely distributed throughout the country but soon after John declared the Charter legally inadmissible it having been agreed to under duress and in July appealed to Pope Innocent III for support in his opposition to it.

He needed little prompting, England was not John’s to give away and he responded the following month declaring the Charter null and void forever and that King John must not even presume to observe it. He also removed Stephen Langton from his position as Archbishop of Canterbury and excommunicated the rebel Barons ordering them to pay their taxes to the King on peril of their mortal souls. The Barons refused to do so and by the autumn the two sides were at war.

By the time Innocent III’s pronouncement reached England he was dead. The new Pope Honorius III preoccupied with the recovery of the Holy Land refused to intervene.

Even so, the war started well for John who captured the powerful Rochester Castle after a prolonged siege and seemed on the verge of re-occupying London but the prospect of once more falling under the thumb of a vengeful John drove the rebel Barons to offer the Throne of England to the French Prince Louis, son of Philip Augustus, who readily accepted - it was by any definition of the term, an act of treason.

In November, Louis sent a detachment of knights to defend London and the following May 1216, he invaded England with an army of 7,000 men. John seeing nothing but enemies wherever he looked fled with a baggage train of treasure to Winchester and later when retreating further north he lost most of it crossing The Wash in Lincolnshire, including the Crown Jewels. Within months of his arrival Louis and the rebel Barons had occupied most of southern England.

On 18 October, John, much to the delight of his enemies and to the relief even of some of his friends and supporters died having feasted a little too heartily and contracting dysentery as a result. But he at least had left an heir, his 9-year-old son, Henry.

William Marshal, appointed the young Henry’s Guardian and Regent of England during his minority, summoned the loyal Barons and hastened to Gloucester Cathedral to have him anointed King of England and pre-empt Louis. He then re-issued Magna Carta but with amendments intended to soften its impact on the Monarchy, but he remained militarily weak and the re-issued Charter was summarily rejected by the Barons - and so the war continued.

In May 1217, learning that a large portion of the French Army was besieging Lincoln Castle far away from its base in the south-east of England, Marshal seized his opportunity.

Lincoln Castle was being held by the remarkable 67-year-old Nicola de la Haye who had remained loyal to King John throughout his troubles and would likewise remain loyal to his son. Gathering his forces at Newark, Marshal advanced on Lincoln where in his haste to do battle he did not even pause to don full armour but stunned by the violence of the attack the French Army was routed and many prisoners taken including 46 of the rebel Barons. When the reinforcements sent for by Louis were defeated in a sea battle off the coast of Kent he was forced to withdraw his army back to France and in September, he renounced his claim to the English Throne. With so many of the traitors in his hands Marshal would have been justified in imposing a lethal sanction but his priority was in securing the crown for the young Henry and the preservation of the dynasty so rather than exact revenge in November he re-issued the Charter once more.

Giving his enemies what they sought at the very moment of their defeat was a remarkable act of foresight and statesmanship and provided evidence that he was perhaps the only man who could have reconciled the rebel Barons to being ruled by the son of their hated enemy.

The new Charter was more expansive than the original following work by Stephen Langton who had previously been more concerned with maintaining the independence of the Church but now helped in the issue of the separate Forests Charter that accompanied it, and extended the definition of what constituted a Free Man, a term which did not specifically exclude women from falling within the remit of its understanding.

With their cause greatly weakened by the withdrawal of their French ally and the objectives they had sought seemingly achieved; the Barons abandoned the fight.

William Marshal had triumphed in securing the dynasty and in doing so also helped save Magna Carta.

On 14 May 1219, having just a few days earlier been initiated into the Knights Templar, William Marshal died, aged 72. He was buried with great ceremony in Temple Church, London, where Stephen Langton providing the eulogy referred to him as the greatest knight.

Henry III, who was to be no less dismissive of the Charter than his father had been, was nonetheless happy to reissue it in 1225, when he thought, it would help facilitate the raising of taxes.

But, like father like son, Henry III’s fractious relationship with his Barons was to lead to the far more serious rebellion of Simon de Montford, the Provisions of Oxford, and the eventual ascendancy of Parliament.

In 1297, the Charter was reissued by King Edward I, or Longshanks, and was entered into the Legal Rolls, or Statute Book, thereby becoming enshrined in English law. It could now only be amended or changed with the consent of Parliament.

Its Second Article or Confirmation Clause reads:

If any judgement be henceforth given contrary to the points of the Charter aforesaid by the justices or by any other of our ministers that hold plea before them against the points of the Charter, it shall be undone.

For the first time the Charter would be referred to as Magna Carta, or Great Charter, and its influence, if not its significance, has waxed and waned over time.

With its preamble often read out at the State Opening of Parliament it was viewed for much of the 15th and 16th centuries more as the bulwark of a resurgent Monarchy than any restraint upon Royal power. This changed during the early decades of the 17th century when the eminent lawyer Sir Edward Coke tried to insinuate Magna Carta into the day-to-day application of English jurisprudence. In this he was largely unsuccessful, but his efforts again raised the profile of Magna Carta and greatly influenced many of the King’s opponents in Parliament in the crisis that led to the Civil War.

Published in 1765, Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England, the classic text on the Principles of English Common Law takes as its starting point Magna Carta and identifies three basic and fundamental rights, the right to life, the right to liberty, and the right to property. From these emerge ancillary rights; the rights and privileges of Parliament, the right to restrict the Royal prerogative, and the right to impose limitations on the Executive.

By the late Victorian era Magna Carta had become a shibboleth of law cast in stone and inviolate even if most of its articles no longer resonated or remained on the Statute Book.

It had become not just a practical working document but a part of English folklore that along with Arthurian Legend, Robin Hood, and the notion of the Freeborn Englishman encompassed notions of liberty, equality, and justice.

Eleanor Roosevelt, who chaired the Commission that drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights upon its ratification in 1948, proclaimed it a Magna Carta for all humanity.

** See also: Simon de Montford: The Provisions of Oxford

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval

Share this post: