Marie Antoinette: The Austrian Whore

Posted on 20th January 2021

She was one of the most reviled figures in history believed to be sexually amoral, corrupt, and indifferent to the suffering of others; blamed for her country's many ills she was genuinely despised in her own lifetime and most of her subjects wanted her dead. Why? What did this woman do to bring such public opprobrium upon her head?

Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna von Hapsburg-Lothringen, a Princess of Austria, was born on 2 October 1755, the youngest daughter of the Austrian Emperor Francis I and his wife Queen Maria Theresa.

Despite her reputation as something of a martinet the Empress Maria Theresa ran an informal Court, and the Royal children were allowed to run free. As a result, the sweet irrepressible Princess Maria Antonia had an idyllic childhood. She enjoyed the outdoors, liked to engage in games and learned the harpsichord. But her education suffered as a result and even as a teenager she could barely read and write.

In August 1765, Francis I died and the formidable Maria Theresa, a mother that the young Maria Antonia barely knew and for the most part lived in fear of, became Regent during the minority of her brother, Joseph.

The Royal children continued their carefree existence, at least for the time being, but Maria Theresa was not a woman given over to frivolity and as far as she was concerned they were assets to be nurtured for future use, and what she was eager to secure was a marriage alliance with Austria’s traditional rival, France; but in 1767, tragedy struck when a smallpox epidemic took the life of her sister Maria Josepha and almost killed her other sister Maria Elisabeth. It had been planned for Maria Elisabeth to marry Dauphin Louis, but the smallpox had left her facially scarred and disfigured. The only remaining candidate was Maria Antonia.

Maria Theresa now ordered that her daughter’s education be more rigorous and Maria Antonia who was elegant, an accomplished dancer, and well-versed in the art of the decorous would now have to learn French, Latin, how to read Court documents and be able to run a household. She neither took kindly to it nor excelled at it.

Later that year, in some haste should further tragedy strike, the twelve-year-old, Maria Antonia was betrothed to Louis, two years her senior.

The French delegation at the marriage negotiations complained that the young Maria Antonia’s teeth were crooked, and three months of excruciatingly painful corrective dental surgery was undertaken without anaesthetic after which it was said her smile was radiant.

At the official wedding ceremony which took place three years later, on 16 May 1770, in the Palace of Versailles Marie Antoinette, as she was to be now to be known, was described as a tall, pale-skinned, ash-blonde young woman with piercing blue eyes. Yet despite the best efforts of so many she still wasn’t considered pretty, and she remained self-conscious and bemused by the formality of Court life. remaining silent for long periods and when forced to speak she did so nervously and quickly.

Discomfited by the attention she now received she adopted a bearing that made her appear haughty and aloof, an image that would come back to haunt her. Nonetheless, she was well-received by the crowds that thronged the streets to greet her arrival in Paris. Louis however, himself a plump, shy, nervous young man and less than decorous than she, did not seem taken by the occasion at all.

A Royal marriage was expected to be consummated on the night of the wedding and the Court waited anxiously to be informed that this had indeed happened, but nothing happened, and it wasn't to happen for another seven years.

Louis had no interest in his new young wife. Indeed, he didn't appear to like her very much, and they barely spoke. He was much happier in his workshop practising his lock-making skills or out hunting with his friends. Marie Antoinette, neglected by her husband gambled, played cards late into the night, and indulged her young woman's love of fine clothes and jewellery. It wasn't long before their 'sham' marriage became a laughing stock.

It was in these early years that her reputation as a frivolous, uncaring aristocrat first took hold and throughout this period of her life she was constantly bombarded by critical letters from her mother that were little short of outright abuse. She accused her daughter of lacking dignity, losing her attractiveness, and of being unable to sexually arouse her husband. Marie Antoinette could barely stand to read these letters let alone pen a reply.

On 11 June 1775, Louis was Crowned King Louis XVI of France and it was no longer tenable that this barren, loveless marriage could be allowed to continue.

In April 1777, the recently Crowned Emperor Joseph I of Austria visited his sister and brother-in-law in Paris and going on a walk with Louis in the grounds of Versailles he took the young King to one side and explained to him the requirement of producing an heir. He demanded that Louis make love to his wife and even went on to explain in the most explicit detail how to do it.

In the meantime, Marie Antoinette starved of affection from her husband sought it elsewhere. She had become particularly close to two ladies of the Royal Court, the Duchesse de Polignac and Princess Lamballe and with the whole of Europe aware that she was receiving no sexual gratification from the King rumours of misguided affection and unnatural practice soon began to spread.

Already referred to in France as L’Autrichienne, or the Austrian Whore such rumours only damaged her reputation further, and it was being said that she was not married to the King at all but wed instead to greed and carnal excess with the most graphic and vile pornographic literature already circulating on the streets of Paris.

The Emperor Joseph's little pep talk had done the trick however, and on 19 December 1778, Marie Antoinette gave birth to a daughter, Marie Therese.

A Queen's pregnancy was considered a public event and the Royal Court were invited in to witness the birth. So on the night itself the Royal Bedchamber was packed with courtiers present to witness the moment and hear the agonising screams of Marie Antoinette as her doctors struggled to deliver the baby while she almost bled to death. Louis, out of concern for his wife and to spare her any further such indignities soon after banned the practice.

With motherhood came greater responsibility and a new relationship with her husband the closeness of which now shocked many at Court. It would appear that they were at last a married couple and Marie Antoinette now began to display the mantle of dignity that was expected of a Queen. For his part Louis at last began to appreciate his wife and a, genuine warmth developed between them bringing some at least to suggest that he had indeed fallen in love. He had the Trianon Garden turned into a rural idyll for her where she could relive her childhood and play at being a country girl milking cows, feeding chickens and tending to the lambs. These were the sort of games Marie Antoinette had always enjoyed. But it would be wrong to suggest that everything was rosy in the garden. Louis remained reluctant in the bedroom and Marie Antoinette continued to have affairs. She was particularly close to a dashing Swedish aristocrat Count Festen, whom she would always turn to at times of great stress.

Her presumed affairs were common currency on the streets of Paris and the literature portraying her as a lascivious sexual predator were all too readily available and it was said only the poor, fat, impotent, cuckolded Louis seemed unaware of them.

On 22 October 1781, Marie Antoinette at last gave birth to a son and heir Louis Joseph, and four years later on 27 March 1785, she gave birth to a second son, Louis Charles. She had done her duty then as a Queen, even if many of the people doubted whether King Louis was the father.

She may have been Queen and mother of the Royal children but any hope of Marie Antoinette being redeemed in the mind of her subjects was to be destroyed by the Affair of the Queen's Necklace. It would tarnish her reputation beyond redemption and bring into disrepute the very existence of the institution of Monarchy itself.

In 1772, the previous King, Louis XV, had commissioned the Parisian jewellers Boehmer and Bassenge to make a spectacular necklace for his lover the Madame du Barry. No expense was to be spared and it came to be valued at over 2,000,000 livres. Unfortunately for the jewellers Louis died before it could be paid for, and the cost of its creation had almost bankrupted them - they were desperate to sell it. Surely, the ever-extravagant Marie Antoinette would purchase it and on every occasion worthy of celebration they tried to sell it to her. But she was no longer the Marie Antoinette of old. She was a mother, a devoted wife, and a responsible Queen. Her days of excess were at an end. Moreover, she wanted nothing to do with a courtesan as disreputable and notorious as the Madame du Barry. Still, they kept trying.

In 1784, a woman named Jeanne de la Motte who claimed to be a descendant of Henry II and liked to use the Royal name Valois became the lover of Cardinal de Rohan.

The Cardinal was an ambitious and duplicitous man who had previously conspired against the Queen and as a result had acquired her displeasure which had seen his status at Court diminish. He was desperate to worm his way back into her favour and De la Motte who told him that she was a close friend of the Queen's promised she would have a word on his behalf. She even produced letters written to her from the Queen that proved they had a deep affection for one another. They were in fact forgeries, but the Cardinal took them at face value and in particular those pages where the Queen appeared to express regret for his banishment from Court. He begged Jeanne to arrange a meeting with the Queen - she agreed to do so.

On a dark but moonlit night in August 1784, Cardinal de Rohan met a woman in the Gardens of Versailles whom he believed to be Marie Antoinette. She was in fact a prostitute who bore a striking resemblance to the Queen named Nicole Leguay d'Oliva hired by de la Motte for the role. They exchanged only a few words before de Rohan presented her with a rose and she promised to forgive him his past duplicity.

Hearing from the Cardinal and others of Jeanne's apparent close relationship with the Queen the Jewellers Boehme and Bassenge approached her in yet another attempt to sell their necklace. She again agreed to speak to the Queen on their behalf but was in fact determined to procure the necklace for herself. She told her lover, the Cardinal, that the Queen wanted to purchase the necklace but could not be seen to do so and whether given their recent reconciliation he would be willing to secure it for her. He was only too delighted to do so. He approached the Jewellers telling them he had been ordered to negotiate the purchase of the necklace on behalf of the Queen and handed over to them notes supposedly from Marie Antoinette (in fact, forged by de la Motte) promising to pay the 2,000,000 livres in instalments.

The necklace was presented to him and he in turn handed it over to someone he believed was the Queen's valet. He was in fact Jeanne de la Motte's husband. When in the following days no payment was received representatives of the Jewellers approached the Queen directly who curtly informed them that she had no knowledge of the affair.

The plot now quickly unravelled and on 15 August 1785, the Cardinal de Rohan was arrested and three days later so too was Jeanne de la Motte.

In May 1786, those involved in the Affair of the Queen's Necklace were brought to trial in a case that scandalised all France. The Cardinal de Rohan had been made to look a fool but considered little more than a dupe he was cleared of all charges with his only punishment to be banned from the Royal Court for life. Likewise, the prostitute Nicole Leguay d'Oliva was also cleared of all charges. Jeanne de la Motte, however, was sentenced to be flogged, branded, and then to spend the rest of her life in prison; and she was indeed stripped naked and whipped in public but managed to weasel her way out of prison after only a year.

The real victim of the Affair of the Necklace was Marie Antoinette. She was of course blameless but few people in France believed so. It all too well fitted in with her popular image as the woman who partied while her people starved, gambled when they had no money, and dressed extravagantly while they wore rags. She may never have said “let them eat cake" but she probably would have done given the opportunity to do so. Her reputation once now lay in tatters - the King, it was said, was a decent enough fellow but his Queen was a bitch and a whore.

By 1787, France was a country in turmoil, a series of failed harvests had left many close to starvation, the Royal Treasury was empty, and the economy close to meltdown. The situation was made worse by a disjointed tax system which left many of the better-off exempt from paying it thereby making the raising of extra revenue almost impossible. The poor could only be squeezed so much.

The King unable to govern effectively through his personal rule was forced to convene the Estates General (the elected legislature of France last summoned in 1614) to address the issue.

Marie Antoinette, whose political influence over her husband had always been minimal now begged him not to do so saying that if he did his power would be reduced and the dynasty threatened. He replied that he no choice. When, the Estates General ignored his rulings and refused to disband when ordered to do so Marie Antoinette felt vindicated. She now demanded that Louis take a hard-line and call in the army to disperse them, but the King shrank from bloodshed.

On 14 July 1789, everything changed when the storming of the Bastille turned what had been a crisis into a revolution. Marie Antoinette again begged the King to use the army to disperse the mob, but Louis doubted their reliability and the thought of Frenchmen being called upon to kill other Frenchmen horrified him. He was indecisive and didn't seem to know what to do. Marie Antoinette who had so often appeared feckless was now displaying the strength of character that her husband so clearly lacked. She actively conspired against the new Revolutionary Government and wrote numerous letters to her brother Joseph, the Austrian Emperor, requesting that he intervene militarily on their behalf. She may have been Austrian by birth, but she was a French Queen and by doing this she also knew that she was committing treason.

On 5 October 1790, a mob of mostly women from the poorer districts of Paris descended on Versailles. They were desperate for bread and demanded that the King open the granaries. He agreed to do so but this failed to satisfy them, and they refused to leave. The following night a group of these women burst into the Queen's bedchamber with the intention of murdering her but hearing the commotion she escaped through a secret passageway to the King's room.

The following morning the Royal Family were forcibly removed from Versailles and handed over to the Revolutionary Government in Paris which promised to protect them if they remained in the Tuilleries Palace.

The experience of 6 October, despite an outward appearance of calm had traumatised even further an already frightened Queen who now feared not only for the safety of herself and her husband but also for the children. She began to plot an escape. Louis would still have the final say but he seemed paralysed by events and incapable of making a decision. So, it was Marie Antoinette and her long-time lover Count Fersten who would make the arrangements.

On the night of 20 June 1791, the family disguised as servants set out in a single carriage hoping to reach the Royal Fortress at Montmedy. They got as far as the small town of Varennes just a few miles from their destination when they were intercepted and stopped by the local postmaster, Jean-Baptiste Drouet. Despite his disguise, Drouet recognised the King, he said from his likeness on a banknote. The Squadron of Cavalry sent from the Fortress to escort them to safety never arrived and instead they were placed under arrest before being taken back to Paris in triumph.

There could now be little doubt that the King opposed the Revolution and his subsequent trial and the abolition of the Monarchy that followed became inevitable. The stony silence that greeted their arrival back in Paris would seem to indicate that the people knew this to. As for the postmaster, Jean-Baptiste Drouet, he became one of those little remembered people who had inadvertently changed the course of history.

The Royal Family were now effectively prisoners of the Government, but this did not prevent Marie Antoinette from continuing to conspire against them and when in April 1792, France declared war on Austria she could barely disguise her delight that at last rescue might be at hand.

Unfortunately for Marie Antoinette, Joseph had died the previous year and been replaced on the throne by her other brother, Leopold. She did not share the same close relationship with Leopold as she had with Joseph, and they had in fact not spoken for twenty-five years. Even so, she wrote to Leopold begging him to come to her rescue and expressed her wishes for a swift Austrian victory.

Leopold would of course do all he could but for him the war with France was about power not family. He wanted to see the Revolution defeated and a weakened France, the restoration of the Monarchy was of secondary concern as sadly also was the fate of his sister.

On 10 August 1792, the Paris mob attacked the Tuilleries Palace. The King's 1200 strong Swiss Guard fought bravely to protect the Royal Family but were overwhelmed and massacred almost to a man. Louis, Marie Antoinette, and the children were forced to flee in desperation to the Legislative Assembly where they were hidden under tables until the Marquis de Lafayette could muster the National Guard for their protection.

Less than a month later, on 3 September, guards opened the prisons, and the mob went on the rampage murdering almost 2,000 inmates, mostly jailed aristocrats and known opponents of the revolution. One of whom was Marie Antoinette's old friend the Princess Lamballe whose severed head they stuck on a pike and paraded beneath the Queen's bedroom window. She refused to look upon it.

On 21 September 1792, the Monarchy was officially abolished. The war against Austria which had at last turned in France's favour had ended any last possibility of rescue.

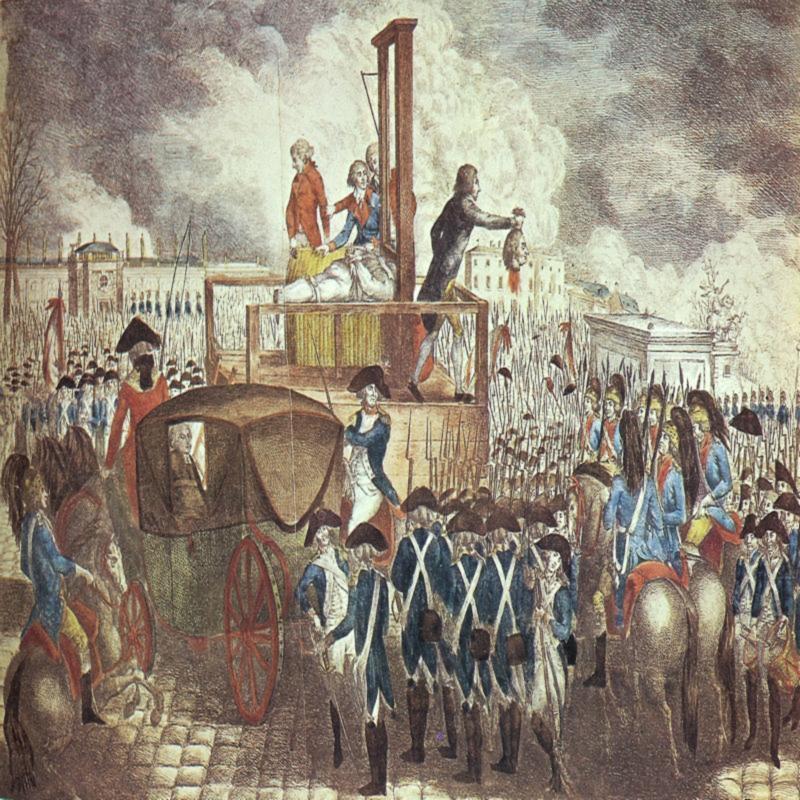

In December Louis Capet, as he was now disparagingly known was put on trial for his life. The charge was treason, and he was found guilty by an overwhelming majority. The decision to execute him however was a hotly debated issue and passed in the Legislature by just two votes. Louis had a last visit from his family a few nights before his execution but refused to see them again. He went to his death it is said with great dignity.

It was now only a matter of time before Marie Antoinette herself was brought before the Court.

Unlike Louis, whose execution was seen as just but still elicited sympathy from the public with even Robespierre feeling obliged to state that the execution of the King was nothing personal merely a political necessity. Marie Antoinette would receive no such understanding. She was truly reviled, and no fate would be too harsh.

Marie Antoinette was now placed under twenty-four-hour watch and there would be guards present even when she bathed and undressed for bed. Her gaolers were harsh and unsympathetic. Most of her requests were denied and she was frequently subjected to verbal abuse. Whenever she was interrogated, her hands were bound even though she asked why that was necessary and requested that they shouldn't be. She was also deeply hurt by her children being taken from her care.

On 14 October, she was brought before the Revolutionary Tribunal and charged with conspiring against the Revolutionary Government, which was undoubtedly true, and of spending millions of livres of the peoples' money on herself and her friends, which almost certainly wasn’t. Most damaging and hurtful however was the accusation that she had sexually abused her son, Louis Charles. The young Dauphin had been bullied into testifying that this was true something his sister would never forgive him for, though his mother did.

Marie Antoinette refused to recognise the charge and it was only under constant provocation that she at last turned towards the women in the Court and said: "If I have not replied it is because nature itself refuses to respond to such a charge laid against a mother."

A ripple of sympathy went about the Court as people realised it was not a Queen, they were trying but a woman, and a mother. But it was to make no difference to the outcome of the trial. This was the people’s revenge, and the verdict was guilty. She would endure the same fate as her husband when two days later on 16 October 1793, Marie Antoinette went to the guillotine.

On the morning of her execution, she appeared calm and spoke only in soft tones. She had no desire for recrimination she said and appeared resigned to her fate. She expressed only concern for the future well-being of her children.

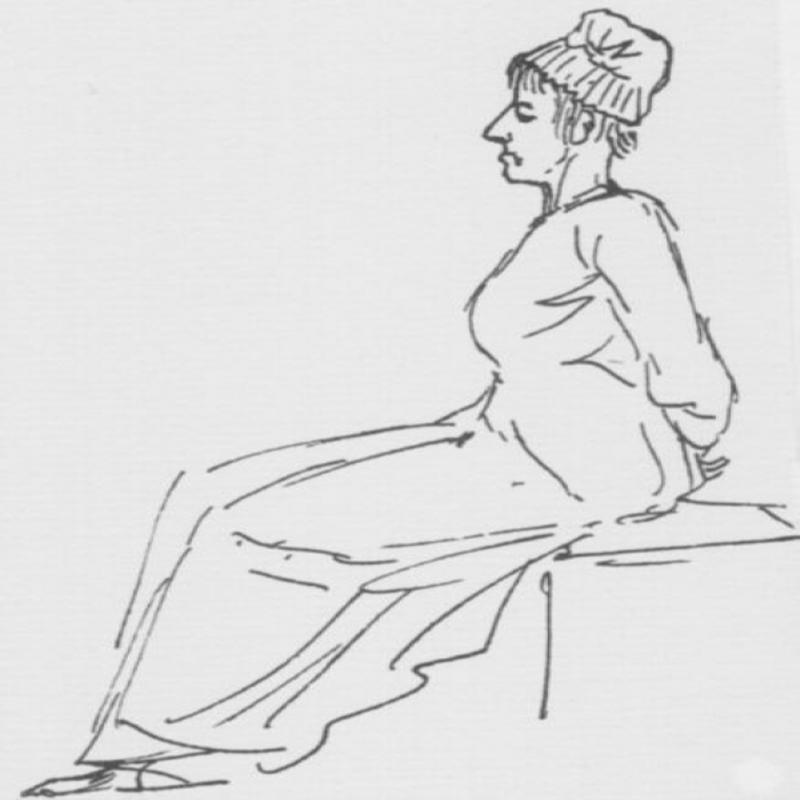

Her hair was cut short, and she was dressed in the plain white smock and cap of a peasant woman. She was then bound and placed in the open cart that would take her to her place of execution.

Paris had turned out in force to line the route to the Place de la Revolucion to witness the execution they had so long sought; they threw missiles, shouted abuse, and some even got close enough to spit on her. Indeed, it was feared she might be murdered before she even reached the scaffold. Those who witnessed the scene would later say, unsurprisingly given her ordeal, how she looked drawn and haggard and much older than her thirty eight years.

Despite all the abuse Marie Antoinette maintained her composure, held her head high throughout and looked straight ahead. One of those present, the artist Jacques-Louis David, who would sketch her on her final journey was unimpressed. It was just a last display of her innate arrogance. He felt nothing but contempt.

On the scaffold she made no attempt to address the crowd merely apologising to the Executioner for accidentally standing on his foot before going quietly to her death.

Like Louis before her she had, no doubt to the ire of those present, displayed only great dignity in her final moments. When her head was held up to the crowd it was greeted with hoots of derision and howls of delight. The Paris mob had got what they had wanted the Austrian Whore was dead!

Yet even in death the hatred remained and in a final indignity Marie Antoinette was denied a Christian burial and her remains disposed of in an unmarked grave.

Share this post: