Massacre at Wounded Knee: Spirits in the Twilight

Posted on 15th October 2021

On 26 June 1876, on the plains of eastern Montana near the Little Big Horn River warriors of the Sioux and Cheyenne Indian Nation inflicted a crushing and humiliating defeat upon the soldiers of the Seventh Cavalry under the command of George Armstrong Custer.

Every soldier under Custer’s personal command was killed and it was a defeat that was so unexpected that it shook the entire country and made legends of the Indian leaders Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. But it was to be the final victory of the Native American people and a pyrrhic victory. Even so, it would not be easily forgotten or forgiven.

Following the Battle of the Little Big Horn or the Greasy Grass as the Indians called it the Sioux Nation were forced to flee north across the border and into Canada. The Canadians did not welcome their presence but did nothing to remove them. Instead, after four years of hunger and neglect Sitting Bull, who had refused to surrender or accept the promised pardon, was forced to yield for the sake of his people and they returned to the United States where he gave himself up to the Authorities.

The American Government would never again take the Indians lightly and they were determined to prevent another Little Big Horn from ever happening again. The Indian problem was to be resolved once and for all and the policy of the U.S Government was to persuade the Indians to embrace the white man’s ways. If need be, he would be forced to do so. One aspect of this policy was to destroy Indian language and culture.

The life of the Plains Indian would come to an end and they would be made to farmland, and their children would be removed and educated in boarding schools by white teachers. This at least was the theory. In practice the Bureau for Indian Affairs that had been established to provide for the needs of the Native Indian people was notoriously corrupt and was often simply used as a cash-cow by its officials.

The Indians were deprived of food, medicines, and basic supplies as these were kept by Agency officials and sold on elsewhere. Experiments in agriculture largely failed, the Indians were hunters not farmers, and life on the Reservations was miserable as the Indians languished, starved, and froze. In extremis many Sioux looked to the spirits of their ancestors for salvation.

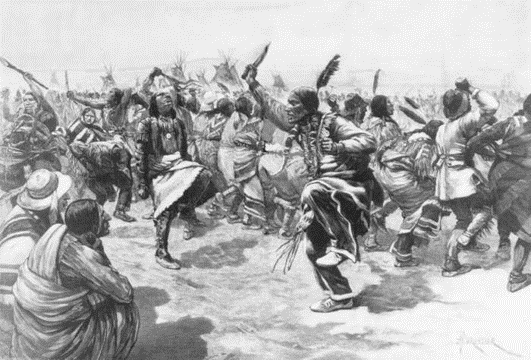

In early 1890, a craze swept through the Indian Tribes settled on the Reservations of the mid-West. It was the Ghost Dance, an ecstatic dance of renewal that would see the old world restored and the white man disappear.

The Indians would form a circle around a Holy Man who would communicate with the spirits of recently deceased ancestors. Raising his arms to the sky and in a trance like state he would exhort those dancing to ever strenuous efforts only then could the prophecy become true.

Many of the dancers wore Ghost Shirts which they believed made them impervious to bullets, but it was not a war dance but a millenarian experience, yet one embraced with such enthusiasm by its adherents that it disturbed and frightened the Authorities. Tensions began to rise as the Government struggled to find a way to cope with something they did not understand.

On the Pine Ridge Reservation the Agent in charge was so concerned that he requested troops be sent to maintain order, but this merely served to increase tensions even further and the Government with white settlements to protect and the Little Big Horn still fresh in the memory were concerned particularly as many of the Indians had been given permission to hunt and were armed – would they again leave the Reservations? Was this the prelude to an Indian uprising? How should they respond?

When Chief Sitting Bull indicated that he was willing to join with the Ghost Dancers the Authorities, who could not tolerate this legendary old Indian embracing the movement, on 15 December 1890 sent 40 Indian Policemen to arrest him. Sitting Bull refused to surrender himself however, and in the struggle that followed he was killed along with eight Sioux and six of the Policemen.

Following the fracas many Lakota Sioux fled the Reservation and joined Sitting Bull’s half-brother Black Elk who was travelling with his people to the Pine Ridge Reservation which had become the spiritual home of the Ghost Dance movement when they were intercepted by 365 Troopers of the Seventh Cavalry and forced to make camp at Wounded Knee in South Dakota. The Army intended to disarm the Indians as a prelude to transporting them to Omaha in Nebraska.

The Cavalry were led by Colonel James W Forsyth, an experienced Officer and Civil War veteran who during the night had the Indian camp surrounded by his soldiers some of whom were manning Hotchkiss machine guns.

On 29 December, they entered the encampment and demanded that the Indians hand over their weapons. Upon seeing the soldiers, a tribal medicine man, Yellow Bird, began to enact the Ghost Dance ritual. Philip Wells, a mixed blood Sioux Indian Scout serving with the U.S Cavalry later described what he saw:

“A medicine man, gaudily dressed and fantastically painted, executed the maneuvers of the ghost dance, raising and throwing dust into the air. He exclaimed ‘Ha Ha’ as he did so, meaning he was about to do something terrible, and said, ‘I have lived long enough,’ meaning he would fight until he died. Turning to the young warriors who were squatted together, he said, ‘Do not fear but let your hearts be strong. There are many soldiers about us who have many bullets, but I am assured there bullets cannot penetrate us. If they come towards us they will float away like dust in the air.”

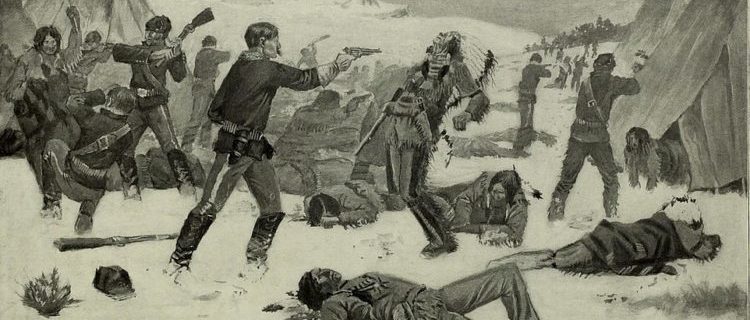

The cry went up from the many women present for the warriors to resist. They were after all wearing Ghost Shirts, they could not be harmed. A tense situation was threatening to get out of hand when a Sioux Indian named Black Coyote (who was reputedly deaf) refused the order to hand over his rifle. Despite being told by other Indians that he could not hear the order the troops tried to physically disarm him and in the melee that followed it seems some Indians opened fire on the troopers who immediately responded in kind.

The fire was random and indiscriminate and as the soldiers and the warriors fought it out the women and children began to flee, and it isn’t in the fighting that Wounded Knee caused such controversy but in the massacre that followed.

The soldiers had by now lost all sense of discipline and little effort was made to restore order.

Old men in their tents and wounded Indians were slain where they lay, the soldiers then fanned out across the plains in pursuit of the women and children who were ridden and cut down. It was a brutal and chaotic scene and the blizzard that had blown up just added to the horror.

By the time it was all over 170 Indians lay dead with many others wounded and left on the plain to freeze to death. The army had lost 25 men killed and 39 wounded.

The Massacre at Wounded Knee was a tragedy, but it was not indicative of a policy of genocide on the part of the Government. It was never their intention to massacre the Indians but a combination of arrogance, neglect, casual racism and a heavy-handed approach that had only served to inflame an already tense situation.

The fact that Colonel Forsyth, a veteran of so many campaigns against the Indians and others was unable either to control the situation or maintain discipline among his men is something that remains very much to his detriment.

At first the events at Wounded Knee were well-received with Colonel Forsyth seen as having prevented a major Indian uprising and in doing so to have avenged the 7th Cavalry and restored their honour but the stripping of the bodies, the many scalping’s, the looting, and the reported abuse of Indian women was a particularly unsavoury aspect of events and when news of this began to filter through public opinion turned against the army.

Few people, particularly in the East any longer thought the Indians posed a threat and what had been reported as a battle was soon perceived to have been a massacre.

In an attempt to assuage public disgust and anger the Government awarded 20 Medals of Honour to those soldiers who were involved, the most in any single engagement in American military history, but it did little to change public opinion, and many were later revoked.

The Indian would never again pose a threat, perceived or otherwise, it was the twilight before darkness descended.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous

Share this post: