Mutiny on the Bounty

Posted on 23rd January 2021

William Bligh was to have an outstanding career both at sea and as a colonial administrator but though respected by his peers and admired by his superiors it was a career dogged by controversy throughout and he is best remembered now for just one incident - the mutiny on His Majesty’s Ship Bounty.

Born in Plymouth on 9 September 1754, the son of a Customs Officer, the sea was to be his life having been provisionally enrolled in the Royal Navy at the age of just seven.

Held in high regard for his seamanship in 1776 he was hand-picked by the explorer James Cook to command a ship on his third and final voyage and would later receive plaudits for his behaviour during the Battle of the Dogger Bank, but he was also a prickly character not easy to get on with both for those who served under him and his superiors at the Admiralty.

Yet he was an educated man with sophisticated tastes and by no means a brute but rather a humane Officer by the standards of his day who chose to spare the rod rarely imposing physical punishment or indeed restraint upon miscreants preferring a tongue lashing to the brutal use of the lash itself. A reluctance to shed blood did not indicate leniency towards ill-discipline however, neither did it make him any more liked for not doing so.

Having served for several years in the Merchant Marine, Bligh returned to the Royal Navy where, re-commissioned as a Lieutenant he was given command of HMS Bounty, and though not yet formally a Captain he was nonetheless Captain of the ship. But unlike most of His Majesty’s warships Bounty had not been provided with a contingent of Marines an oversight that would prove significant in light of events.

On 15 October 1787, the Bounty sailed from Deptford on its voyage to the Pacific Islands to gather breadfruit plants for transportation to the West Indies where they were intended to provide a cheap staple diet for the slave population working the plantations.

The outward-bound journey was to prove relatively trouble free with Bligh heavily reliant upon his First Mate Fletcher Christian, an old friend with whom he had sailed twice before to be the conduit to the rest of the crew with whom he struggled to communicate.

Fletcher Christian was a Cumbrian man of rough but not coarse manner who spoke the language of the common sailor and was widely trusted. No contemporary image of Fletcher Christian exists but we do have Bligh’s description of him:

Christian was 5 feet 9 inches in height, blackish or very dark complexion, his hair blackish or very dark brown. A star tattooed on his left breast and on his backside. His knees stand a little bit out and he may be called bow-legged. He is subject to violent perspiration particularly in his hands, so that it soils anything he handles.

And he would need Christian for he was to prove a fussy and meddlesome ship’s master.

Bligh demanded greater personal hygiene from his men and drove them obsessively to maintain cleanliness aboard ship washing clothes, polishing utensils, and clearing the decks all of which seemed unnecessary on such a long voyage and although, he was loathe to spill blood to maintain discipline on one occasion at least he ordered the lashing of a man for disobedience and he certainty wasn’t adverse to cancelling the crews rum ration or restricting their food to a bare minimum as punishment. Similarly, his propensity for verbally abusing those he thought negligent or lazy in front of others became an increasing cause of friction.

The Bounty arrived at Tahiti on 28 October 1788, and after so the many arduous months aboard ship bathed in warm sunshine and with its abundance of food, soporific lifestyle, and the ready availability of sex it seemed heaven on earth. It was to turn the heads of many men some of whom took up with Tahitian women and remained ashore rarely returning to the ship.

Bligh did little to prevent this co-habitation but demanded that the breadfruit plants be gathered and stored, the work was done but not without complaint and Bligh now began to suspect that Christian, who he had promoted during the voyage, was behind much of the dissent and he was to upbraid him more than once not only before the men but also the Tahitian natives. The number of floggings dished out to the men now also increased.

The Bounty was to remain in Tahiti for five months and when the time came to depart on 5 April 1789, it was evident that some were willingly to do so only reluctantly - three men stole a boat and deserted but were recaptured and put to the lash, others seduced by months of indolent self-indulgence complained bitterly and Bligh all too readily blamed Christian for failing to maintain order ashore. But he had been no more immune to the lure of paradise than anyone else. With no Marines aboard Bligh’s authority was dependent upon the respect of his men and the loyalty of his Officers, neither of which could be taken for granted.

Being forced to leave their Polynesian idyll caused divisions within the crew manifesting itself in a reluctance on the part of some to do their share of the work. Sensing this Bligh would vent his spleen with the target of his wrath more often than not, Fletcher Christian.

On 22 April, Bligh accused Christian of cowardice after he returned from the Island of Nomuka without the wood he had been ordered to gather claiming that the hostility of the natives had prevented him from doing so. Five days later he was blamed for the theft of coconuts from the Captain’s private stock but instead of punishing Christian alone Bligh reduced the entire crew’s rations.

Ever since leaving Tahiti, Christian had been encouraged by others to seize control of the ship. He had the support of the men they told him. He also believed that upon their return Bligh was intending to blame him for all the woes of the voyage. That he was to be made a scapegoat he all too readily believed. In the end he needed little encouragement.

In the early hours of 28 April, along with a number of accomplices he seized muskets from the armoury, burst into the captain’s cabin and dragged Bligh from his bed tying his hands behind his back. Bligh cried out for assistance, but none came and frog-marched onto deck Christian announced that he was taking control of the ship.

Bligh continued to berate Christian, declaring him a mutineer who would be hanged for treason and demanded he be released imploring the crew to knock him out, to overpower and arrest him, but though most were opposed to mutiny cowed by Christian whose men after all were armed, they were not willing to risk their lives for an unpopular Captain. Christian now acted swiftly, he ordered the ship’s launch to be loaded with provisions and for Bligh and those among the crew who refused to join the mutiny to get in and more than 20 did so and in a boat that was made for half that number.

Four of those who remained loyal to Bligh were kept aboard the Bounty for their expertise, as also were a number for whom there was no room in the launch.

Before the launch was released from the ship Bligh made one last attempt to dissuade Christian from his course of action appealing to both to their past friendship and in the name of his children whom he had once dangled upon his knee. Christian merely replied - I am in hell, sir. I am in hell. And well he might for to all intents and purposes he was sending his Captain and those with him to their deaths.

As the heavily laden launch was cut loose it lay so low in the water that it seemed the merest squall would swamp it but Bligh who had honed his seamanship and navigational skills under the tutelage of Captain Cook never doubted that he could guide it to safety. Armed only with a compass and a sextant he set a course for Coupong in the Dutch East Indies some 3,500 nautical miles away. It was to become one of the most epic journeys in maritime history.

In the open boat there was no protection from the hot sun during the day and the bitter cold at night. It also rained incessantly and with just a single sail progress was slow.

At first, Bligh tried to island hop his way to safety but with no means of protecting themselves from the hostility of the natives this became too hazardous and so he instead decided to remain at sea as much as possible. On rations of just an ounce of bread and a quarter pint of water a day and no immediate prospect of rescue in sight tensions in the boat were high and despite Bligh’s attempts to sustain morale with songs and story- telling he more than once had to threaten violence to maintain order. Some relief came when they passed the Great Barrier Reef and Bligh was able to beach the boat on a small uninhabited Island replete with berries and oysters on which the men gorged themselves.

On 14 June 1789, after 47 days at sea Bligh sailed into Coupong Harbour. His many prayers had been answered. It had indeed been a miracle.

Bligh had lost just one man early in the voyage during a melee with natives on the Island of Tongapatu but six were to die not long after reaching safety from exhaustion, malnutrition, and disease. Reporting the mutiny to the Authorities his outstanding seamanship did little to alleviate the sense of shame he felt as a Captain who had lost control of his ship.

In the meantime, Fletcher Christian sailed the Bounty to the Island of Tubuai where he hoped to establish a colony but despite building a small fort frequent attacks by the native population eventually forced them to flee.

In late July, the mutineers returned to Tahiti where Christian released those, he had been holding prisoner but now found that many of his own men wished to remain also. He warned them that to do so could find them dangling from the end of a noose but having earlier reassured them that Bligh and the others could not possibly hope to survive their abandonment his words carried little weight.

Christian was to marry his Tahitian lover Maimiti, before on 22 September he sailed the Bounty from Tahiti with 9 of the mutineers, 14 native women abducted as concubines, and 6 men to do the work. Before departing he told those he had left behind: I shall run with the wind and land the first place I find. I cannot remain here after what I have done.

He was searching for the uninhabited Pitcairn Island a place he had visited before but knew had not yet been formally located on any map. It would be as safe a haven as any and one where they could create their own society free of interference and the threat of attack, or so he thought.

The mutineers made landfall at Pitcairn Island on 15 January 1790, and immediately undertook creating a settlement stripping the Bounty bare before Christian ordered it burned so there would be no temptation for anyone to leave.

But it was not to be the Utopia he had hoped for as any sense of collaboration and feelings of harmony that may have existed among the mutineers soon disintegrated as life on the island descended into a series of squabbles over land, property, and in particular access to the women.

Drunkenness became commonplace as Christian’s authority waned, and the arguments escalated into violence.

In September 1793, the Tahitian men who had been taken to Pitcairn Island against their will and had since been treated like slaves struck back, and in carefully coordinated attacks five of the mutineers were murdered among them Fletcher Christian who was stabbed and clubbed to death while working his fields, although the rumour persisted for some time that he had escaped and somehow made his way back to England.

Those responsible for the murders were themselves killed in turn and the remaining mutineers now turned to religion as their salvation. By the time the American vessel Topaz stopped off briefly at Pitcairn Island in 1808, they found only one of the original mutineers John Adams, and 46 others mostly the children of his deceased shipmates including Fletcher Christian still alive.

William Bligh arrived back in England on 14 March 1790, to face a court martial for losing his ship but already being lauded as a hero in the press for his triumph of navigation and having the courage to stand up to pirates his acquittal became a formality.

Having provided the Admiralty with a full report in November 1790, the frigate Pandora under the command of Captain Edward Edwards set sail to apprehend and bring to justice the surviving mutineers.

The Pandora docked at Tahiti on 23 March 1791, and with nowhere to run most of the 14 crewmen of the Bounty voluntarily surrendered without resistance, those who did not were soon captured. Captain Edwards was to prove no Captain Bligh as rarely sparing the lash he locked the captives in cages where manacled hand and foot, food, water, and medical care was scant. He remained determined however to apprehend the ringleader of the mutiny Fletcher Christian and continued the search until August but despite finding evidence of their presence he never discovered their hideout on Pitcairn Island.

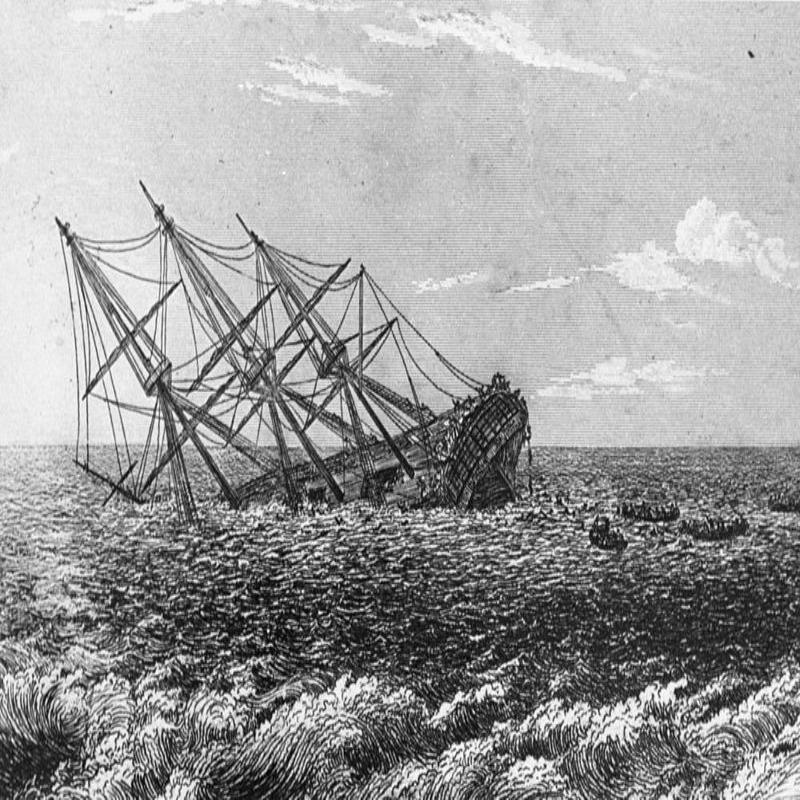

On 26 August, in the midst of a storm the Pandora was driven onto the Great Barrier Reef and ripped apart and as the ship began to sink there was little time to remove the prisoner’s shackles and only at the last moment were they released from their cages. Four of them subsequently drowned, the rest escaped in a boat where they were kept bound until they reached safety.

Returned to England in September the remaining mutineers were put on trial where the four who had been kept aboard the Bounty against their will were acquitted but the other six were found guilty and condemned to hang. Mitigating circumstances cited during the trial would see two of the condemned men pardoned by King George III.

On 28 October, three of the condemned men, Thomas Birkett, Thomas Ellison, and John Millward were hanged from the yardarm of HMS Brunswick in Portsmouth Harbour. The fourth man William Muspratt was hanged later.

Publication of the trial proceedings were to see public opinion turn against Bligh however, as criticism of his captaincy of the Bounty was made manifest and for a time at least he was placed on half pay but Bligh’s career was to continue on its upward curve as he distinguished himself at both the Battle of Camperdown in 1797 and at the Battle Copenhagen in 1801, where he received a personal commendation from Lord Horatio Nelson.

In 1806, he sailed into Sidney Harbour, Australia, as the newly appointed Governor of New South Wales where popular with the common people he was to prove less so with the vested interest and in January 1808, was deposed in a coup d’etat. Yet again his time in charge had been contentious and confrontational.

He had tried to do the right thing, as he so often had before, but he appears to have lacked what we might refer to now as people skills. Indeed, he was to be court-martialled on two further occasions for foul and abusive language to fellow Officers and behaviour unbecoming a gentleman.

Following the fiasco of his time in Australia, Bligh returned to England where he was promoted to Vice-Admiral but was never again to hold a position of authority.

He died at his home in Bond Street, London on 7 December 1817, aged 63, a hero to some and a villain to others.

Tagged as: Georgian

Share this post: