Nelson and Trafalgar

Posted on 17th April 2021

By May 1803, the Peace of Amiens that had seen a brief lull after almost ten years of war between Britain and France was over. The renewal of hostilities was the result of Napoleon Bonaparte’s determination to minimise British influence in Europe, impede its ability to trade abroad and threaten its Empire. Britain’s response was to affect a blockade of French ports and seize any ships bound for them. Bonaparte now demanded that the Continent of Europe cease trading with Britain and much of it had little choice but to comply.

Although it was in no position to fight a land war on the Continent Britain remained determined to resist French hegemony in Europe and so would use its great wealth and abundance of resources to do so instead. Prime Minister William Pitt would finance the formation of the Third Coalition of Austria and Russia in opposition to Bonaparte. It was not the first time that “Pitt’s Gold” had been used to thwart French ambitions, but Napoleon was determined that it should be the last. He gathered his Grand Armee at Boulogne for a planned invasion of England and end once and for all the meddling of this arrogant Nation of Shopkeepers.

Britain was ready for war but ill-prepared for battle, its army remained relatively small, and it had no outstanding General to call upon; and despite its coastal fortifications being strengthened the militia system upon which their defence fell was little more than, a refuge for vagabonds, thieves, and banditi. Few doubted that should Napoleon land his Grand Armee on the shores of England it would in short order be triumphant but then Britain’s military strength did not lie with its army but with its navy and one man in particular – Admiral Lord Viscount Nelson.

But Nelson was a controversial figure whose judgement had been called into question more than once, if not always when on active service then at least in the arrangement of his domestic affairs.

Horatio Nelson was born on 29 September 1758, in the village of Burnham Thorpe, Norfolk, the sixth of eleven children to his clergyman father, Edmund and although his family were of modest means they were in fact well-connected through his mother Catherine Suckling who was the niece of Robert Walpole Britain’s first de facto Prime Minister and the richest man in the country. These connections were to serve Nelson well throughout his career.

At the age of 12 the young Horatio enlisted in the Royal Navy as an ordinary able seaman but his uncle who commanded the ship soon promoted him to midshipman.

Personally courageous and a fine seaman who understood naval tactics and strategy Nelson’s rise through the ranks was to be nothing short of meteoric and by the age of 20 he was already commanding his own vessel.

But then his battle scars would tell their own story – on 19 June 1794, during the successful siege of Calvi in Corsica he was caught in a shell burst that splintered his right eye, told that he would in time lose the use of it he remarked that it was a mere inconvenience for he had another. It was typical Nelson.

Respected by his peers within the navy if not always the Admiralty he first came to national prominence on 14 February 1797, when the British and Spanish Fleets clashed off Cape St Vincent. Fearing that his Commanding Officer Sir John Jervis was about to let the enemy escape he disobeyed orders to break away and attack three ships of the Spanish vanguard.

Nelson appeared to have over-reached himself for in the vicious exchange of broadsides the out-gunned British were clearly coming off worse. But he wasn’t a man willing to accept failure and drawing his sword rallied his men and led a boarding party onto the opposing San Nicolas with such ferocity that he not only swept the defenders aside but went onto board the San Josef that had pulled alongside to assist.

Viewing events from afar Sir John Jervis was less belligerent and much to Nelson’s chagrin the Spanish Fleet though defeated was allowed to withdraw relatively intact. Jervis was to publicly rebuke Nelson for disobeying orders but privately acknowledged that it was his actions that had secured victory, though he omitted such from his official report. Nelson, not willing to be overlooked in such a manner had his own account of the battle published in The Times newspaper.

Following the Battle of Cape St Vincent, Nelson was given command of his own Squadron and ordered to lie off Cadiz and intercept Spanish Treasure Ships arriving from South America. This he did successfully but it was dull work and, in the meantime, he had convinced the Admiralty in London to support his plan to capture the port of Santa Cruz de Tenerife.

It was not a success; the Spanish defences were to prove more formidable than at first thought with a number of boats shot to pieces before they could land and those Marines who made it ashore dispersed over a wide area. Nelson tried to bring order to chaos by leading from the front as he always did but was struck down by a musket ball which shattered the bone in his right arm.

As the attack stalled Nelson’s Officers formed a protective ring around him but the surgeon who was in attendance could do little to treat the wound and had no choice but to amputate the arm.

Nelson returned to England to nurse his wounds in great pain and no little despair as he believed the fiasco at Santa Cruz de Tenerife and his disability guaranteed the end of his naval career but the heroic manner in which he had fallen had enhanced rather than damaged his reputation. Even so, a long period of rehabilitation and the war continuing at sea without him proved a great frustration.

In early 1798, the British became aware that Bonaparte was gathering a large army and many ships in and around the area of Toulon on the Mediterranean coast. It was evident that he was planning a campaign but where exactly remained unknown.

In fact, he intended the conquest of Egypt, a long-cherished dream of the French who considered it the cradle of civilisation, but sentiment aside Napoleon also perceived its strategic value as a place from where he could threaten Britain’s interests in India.

The French Fleet sailed from Toulon on 17 May, bound for Egypt stopping off on the way to seize the Island of Malta for France. Nelson who had since resumed active service was given command of a Squadron and despatched from the main fleet still stationed off Cadiz to find the French Fleet, track its course, and intercept it if possible.

More than once Nelson almost stumbled across the French invasion force, but it wasn’t until 28 July that he at last received intelligence that its destination was Alexandria in Egypt.

In the meantime, Napoleon had disembarked his troops in haste aware that the British Fleet was likely nearby.

Nelson arrived not long after only to find the French Fleet gone, they had moved further up the coast to Aboukir Bay at the mouth of the River Nile where the French Admiral Francois-Paul Brueys had moored it in battle formation.

Although Aboukir Bay provided little obvious protection its waters were shallow and it was thought they would impede Nelson’s manoeuvrability thereby preventing him from launching a sustained attack, and that even if he did try to do so Brueys had moored his ships close enough to the shore to force him into what could only be a frontal assault.

But the shoals of Aboukir Bay were not as shallow as Brueys had imagined and moreover there was more than enough room for Nelson to get between the shore and the French battle line. And it was an opportunity he was quick to exploit isolating the French vanguard and squeezing it from both sides. Caught in a vice like grip it was raked with a fire so ferocious that it was utterly destroyed. Now outgunned and unable to manoeuvre Brueys had no choice but to stand and fight. It was to be a one-sided affair.

Even so, the French fought hard and as a result sustained heavy casualties including Admiral Brueys who shot through and dismembered by a cannon ball nonetheless remained at his post until bleeding to death.

At 22.00 the French Flagship Orient which had been ablaze for some time detonated in a massive explosion that not only tore it apart but severely damaged several other ships nearby killing more than a thousand men.

It was in effect the coup de grace and though some French ships were to resume the fight on the morrow the outcome was no longer in doubt. By the time the fighting ceased 13 French ships had been destroyed or captured with 5,000 men killed and wounded. The destruction would have been complete had not Admiral Pierre-Charles de Villeneuve with 4 ships escaped the carnage under the cover of darkness.

For the loss of no ships and just 267 men killed Lord Nelson had shattered Napoleon’s dreams of a Middle East Empire even if he was to remain in Egypt a further two years plundering it of its treasures and heritage.

When Britain learned of Nelson’s victory at the Battle of the Nile it erupted in an orgy of celebration as people thronged the streets, bonfires were lit, and fireworks blazed across the night sky.

Nelson was praised in an address to Parliament by King George III, awarded a pension of £2,000 a year in perpetuity and received a Baronetcy which would later be raised to Viscount.

Following his triumph Nelson sailed to Naples where he was received as a hero and none more so than by the wife of the Ambassador to the Kingdom of Naples, Lady Emma Hamilton who breathlessly received him with the words, “Oh God, is it possible!” before promptly feinting. If not exactly love at first sight it was certainly seduction.

Amy Lyon, the daughter of a blacksmith who became a dancer, artist’s model and society whore had risen high, but it had been a hard road of failed affairs, abandonment and little dignity. She had for a time been the lover of Sir Henry Fetherstonehaugh but the relationship came to an end when concerned by her continued fecundity following an unwanted pregnancy, he passed her onto Sir Charles Greville who had long expressed an interest.

Sir Charles took her in on condition she changed her name to the more respectable Emma and remained out of sight unless called upon to entertain his guests; but the relationship was only a year old when under pressure to make a good and profitable marriage Emma became an inconvenience to him. Unwilling to do ill by her he persuaded his uncle Lord William Hamilton to take her off his hands.

It was hardly a love match with Hamilton more than twice Emma’s age and he only reluctantly and for the good of the family acquiesced to his nephew’s request. Emma weary of being passed around on sale or return would eventually persuade Hamilton to not just keep her as a mistress but marry her. Now, as Lady Hamilton she did nothing to disguise her admiration for the hero Nelson and they were soon lovers.

As if the very public cuckolding of a high-ranking British official (though it was seemingly done with Hamilton’s approval) wasn’t bad enough Nelson himself was also married.

He had wed Frances Nisbet, a Caribbean plantation owner’s daughter twelve years earlier.

Happier enough at first the marriage soon began to sour in large part due to Frances’s inability to any longer conceive but she remained devoted to her husband tending to his wounds both physical and emotional whenever he returned from sea and caring for his elderly father, but her devotion made her neither interesting nor exciting, Lady Emma was both. Increasingly estranged from his wife Nelson would still write letters to her fulsome in their praise for the beautiful and exotic Lady Emma, her letters to him would later remain unopened.

Nelson’s behaviour scandalised respectable society and the rewards that his achievements might have merited ceased as shunned at high table and already under scrutiny for his cavalier attitude towards orders his judgement now came into question. He was, it was said, no gentleman.

As Nelson flaunted his relationship with Lady Emma often with Lord Hamilton close behind, he accumulated opprobrium but it was only a matter of time before the next crisis would emerge and his services would be called upon once more.

An alliance of Russia, Prussia, Sweden and Denmark known as the League of Neutrality had been formed to oppose Britain’s continuing blockade of European ports. Such an alliance could not be permitted to stand and with negotiations making little progress the decision was made to destroy the combined Danish and Norwegian Fleet stationed at Copenhagen in a show of force. They would have to act swiftly however, before the seas thawed sufficiently to release the Russian Fleet from their ice-bound sojourn on the Baltic coast.

Despite being acknowledged as the outstanding naval commander of his day doubts persisted as to Nelson’s character and so he was once more denied overall command which went to Admiral Sir Hyde Parker, a cautious man who worried by the size of the fleet that opposed him and wary of the fortress guns that protected it dithered loath as he was to commit to an all-out assault. Nelson on the other hand was eager to get under way believing that any delay only played into the hands of the enemy.

At 10.00 on 2 April 1801, Nelson moved his ships into position to attack the weaker end of the Danish line intending to rake and board them one at a time making room for Marines to land and storm the fortress of Tre Kroner. Hyde Parker believed it would be a hard slog and so it turned out.

By midday little progress had been made and peering into the fog that partially shrouded the action from his view Hyde Parker could see three British ships of the line clearly in distress. He signalled to Nelson to cease the attack and withdraw.

BBut by this time superior British gunnery was taking effect and though the fortress was not taken its guns had been effectively silenced and the left of the Danish line was beginning to crumble. Aware of this Nelson put a telescope to his blind eye and remarked to a subordinate, “I really do not see the signal.”

The attack continued and by late afternoon it was clear the Danes were losing but they still possessed a powerful reserve, and the British were exhausted. It would in the end take a combination of bluff and threat from Nelson who showed that he could talk as well as engage in a good fight to secure victory.

It was yet another triumph for Lord Nelson and no one could be in any doubt that the victory had been his and his alone. He had it was said – the Nelson Touch. At last, he received the promotion he had always wanted – Admiral of the Fleet.

Admiral Lord Viscount Nelson possessed that rare quality in a military commander, he was both loved and respected by his men for he not only brought them victory in battle but shared their dangers and he had the scars to prove it. He was also a humane commander by the standards of the day disavowing the more brutal punishments relying instead upon his personal authority to maintain discipline.

On 2 December 1804, at a grand ceremony held at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, Napoleon Bonaparte who had been the effective sole ruler of France since 1799 crowned himself Emperor. That he did so with the Pope present was indicative of his impatience to get the job done. He was no less impatient to eradicate Britain as a threat to his hegemony in Europe and French interests around the world.

As he gathered his Army at Boulogne, he imagined a swift victory but to do that he required control of the English Channel if only for a few days but the powerful Royal Navy stood in his way as did its formidable Commander-in-Chief.

The responsibility for neutralising the British Fleet would fall to Admiral Pierre-Charles de Villeneuve, the same de Villeneuve who had barely escaped the catastrophe at Aboukir Bay eight years earlier.

A very different man to Nelson both in character and temperament he had been born into an aristocratic family that had survived the ravages of the Revolution and was a career naval Officer whose guiding light was honour and honour was something he had been born to not a meritorious badge of recognition earned in battle - he did not feel the need to seek glory.

Villeneuve’s plan was to evade the British Fleet (unlike other British Admirals Nelson did not maintain a tight blockade hoping instead to entice the French into open sea to give battle) and sail West to attack British possessions in the Caribbean thereby luring Nelson away from the Channel in pursuit. He would then link up with the Spanish Fleet and disperse those British ships still on station allowing the French invasion barges to cross the Channel unimpeded. Villeneuve sailed from Toulon in March 1805, easily evading the British blockade.

It proved to be a good plan and Nelson misreading Villeneuve’s intentions at first sailed for the Mediterranean on a wild goose chase before realising his mistake. Unfavourable winds then delayed him further until he was more than a month’s travelling distance behind.

But now Villeneuve dithered, the attacks upon British possessions never really materialised and yet he remained in the Caribbean for another three months doing very little not embarking upon the return journey until news had reached him that Nelson’s Fleet had been sighted off Antigua - the valuable time won had been squandered.

On 22 July, he encountered a small British force off Cape Finisterre and in a brisk firefight two Spanish vessels were lost. It seemed to shake Villeneuve’s confidence and instead of continuing the engagement which should have been a one-sided affair he broke it off and returned to Cadiz in defiance of demands from his subordinates that he not do so. Before long he was blockaded in port once more.

Losing patience with his Admiral on 26 August Napoleon broke camp at Boulogne and marched his army into Germany to counter the threat being posed by the formation of the Third Coalition. For the time being at least Britain was freed from the threat of possible invasion.

When in September, Villeneuve was ordered to break out from Cadiz and sail for the Mediterranean he chose to ignore the order. It proved the final straw for Napoleon who now sought to replace the Admiral writing that: “Villeneuve does not have the strength of character to command a frigate. He lacks determination and has no moral courage.”

It was only now with his honour impugned that Villeneuve decided to act but he did so with trepidation. Nelson would fight of that he could be in no doubt and in doing so he was likely to adopt unorthodox methods. This he knew, but how do you anticipate the unexpected?

Even so, previous experience had taught him that Nelson would likely seek to close and board as soon as possible and so to counter this threat he had recruited some 4,000 mostly Tyrolean sharpshooters to remain high in the rigging and rake the decks of the British ships in any close-quarter combat. He also thought that Nelson’s Fleet was more powerful than his own but in this belief, he was mistaken: The combined French and Spanish Fleet he had under his command consisted of 41 vessels including 33 ships of the line carrying 2,652 guns and 25,200 men. The British Fleet under Nelson had 33 vessels including 27 ships of the line with 2,178 guns and 17, 076 men.

On 18 October, the Franco-Spanish Fleet sailed from Cadiz Harbour but three days later informed that Nelson was approaching Villeneuve once more had a loss of nerve and ordered the fleets return to port, but light winds prevented progress– he had left it too late.

It was standard practice in naval warfare of the time for opposing fleets to form up in line of battle parallel to one another and then exchange broadsides at close range which allowed for easier communication, greater control and increased manoeuvrability but it also ensured that few battles were fought to a conclusion. Such an outcome was simply intolerable to Nelson who was intent on the utter destruction of the enemy, nothing less would do.

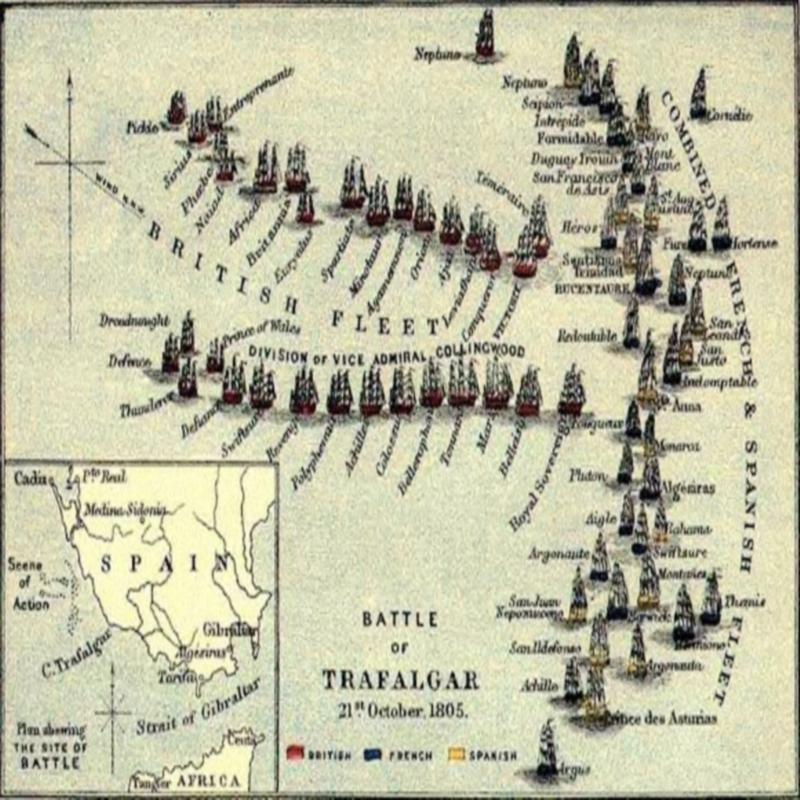

On consecutive nights Nelson dined with his Captain’s and outlined his plan for the forthcoming battle – he would drive straight at the enemy line in two columns piercing it twice thus dividing it into three separate parts and causing chaos as a result. The enemy ships would then be engaged as quickly as possible creating a melee so ferocious and so confused that they would have no time to recover.

Speed was of the essence with no time being given for the separate parts of the enemy fleet to manoeuvre in support of one another and no opportunity given for them to decline battle either.

Nelson had complete faith in the superiority of British gunnery, seamanship and valour and was in no doubt that in any fight they would prevail. Morale amongst the crews was also high with each man from Captain to Cabin Boy knowing his job and the role he had to play.

Such self-assuredness had not been much in evidence in the weeks of shore leave prior to his re-joining the Fleet when his mood could best have been described as melancholic.

He had stayed at the home of the Hamilton’s who were still living together as man and wife where he spent precious time with Horatia his infant daughter by Emma. Although the young Horatia was aware who her father was her mother’s identity was kept from her for many years with Emma claiming only to be her guardian and no more.

Regardless of the gossip and the rumours that surrounded their relationship these were idyllic times for Horatio and Emma but even, so it was noticed how a certain fatalism had come to dominate Nelson’s character - he was uncharacteristically affectionate towards friends and colleagues, spoke often in the past tense and he even at one point visited a leading London undertaker to purchase a coffin.

Despite the contentment he found in the company of Emma and his daughter he remained eager to return to the fleet and get the job done.

Things were very different for Pierre-Charles de Villeneuve who was both under pressure to act and knowing both the ability of his opponent and the state of the navy he commanded fearful of failure. For unlike the Royal Navy which was essential to Britain’s continued dominance of world trade the French Fleet was not the source of Napoleon Bonaparte’s power but merely the means to an end and not an end in itself. As such, many of the crew were inexperienced and poorly trained with promotion the fiefdom of aristocratic privilege attained by right and not on merit. Similarly, the condition of the Spanish Fleet under the command of Admiral Frederico Gravina reflected a power that had been in decline for many years.

Nothing had been left to chance by Nelson, and he confidently predicted victory declaring that at least 20 ships would be taken but still that sense of fatalism remained. As a final meeting with his subordinates broke up he said to the Captain of the Euryalus: “God bless you Blackwood, I shall never see you again.”

Having been dissuaded from wearing his full-dress uniform Nelson donned his second best uniform but adorned as it was with awards, badges and gold braid he became no less a conspicuous and obvious target.

As dawn broke on 21 October 1805, the drums rolled and the men prepared for battle – the big 24 pounder guns were rolled into place, portals opened and the ammunition, large iron cannon balls, grapeshot, and ball and chain designed to tear up and bring down rigging were stockpiled; the cooking fires were doused, the decks were laid with sand and moveable items lashed down as men took up the positions sweat on the their brows, their mouths dry and with a lump in their throats. As the two fleets closed the anxiety was palpable. At 11.45 Nelson raised his famous signal: “England expects that every man will do his duty.”

Villeneuve’s line which stretched for more than 5 miles appeared ragged and poorly organised playing into Nelson’s hands, but he also knew the risks he was running by approaching in column which left his ships vulnerable to the broadsides of the enemy without being able to respond in kind. Also, the numerical superiority of the Franco-Spanish Fleet could see individual British ships isolated and subjected to the sustained fire of two or even three enemy vessels.

Nelson, aboard the Victory led the Windward Squadron on a course directly for Villeneuve’s Flagship the Bucentaure but Captain Eliab Harvey aboard the Temeraire fearing that the Admiral would expose himself to unnecessary danger tried to provide protection by getting ahead of the Victory until ordered back into line.

Finding his way to the Bucentaure blocked by the Redoubtable, Nelson ordered it rammed and supported by the Temeraire opened a ferocious barrage at point blank range on both ships and a little later the approaching Santissima Trinidad.

The fighting was brutal as limbs were torn off by hurtling cannon balls, the decks were raked with musket fire, wood splinters flew everywhere, rigging collapsed, fires broke out trapping men below and many were thrown overboard and drowned. Indeed, so lethal was the bombardment that some of the French who had not seen action before refused to open their gun ports and return fire with many deserting their posts but as they were soon to find out there was nowhere to hide in the confines of a ship.

At the same time as Nelson was engaged in a life and death struggle his Second-in-Command Cuthbert Collingwood leading the Leeward Squadron on his ship the Royal Sovereign also smashed into the enemy line firing a broadside of such ferocity upon the Spanish Santa Anna that it killed or maimed 400 men and disabled 14 guns. Reduced to little more than a hulk the Santa Anna was to surrender soon after.

By this time both fleets were becoming fully engaged and superior British gunnery and the inexperience of the enemy who resisted fiercely in some places but not so much in others was taking its toll as they were increasingly overwhelmed.

Victory was taking fearful punishment from the combined guns of three enemy ships, its wheel had been shot away, broken masts and torn rigging littered the deck, a squad of Marines lay dead and dying their bodies ripped apart by a cascading cannon ball, Nelson’s personal aide was killed as also was his replacement while Captain Hardy had barely escaped with his life on several occasions. Nelson reassured him - this is too warmer work to last long.

But for all the bloody chaos aboard the Victory the French Redoubtable was faring worse and with its gun decks destroyed in a desperate attempt to turn the tide its Captain ordered that the Victory be boarded.

The French fought with great determination and some initial success but the Temeraire coming alongside raked the deck with grapeshot causing great loss of life and repelling the invaders.

Throughout Nelson had been a very visible presence encouraging his men and showing no fear as he strolled calmly along the quarter-deck in the company of Captain Hardy. But at 1.27 pm just as the battle was reaching its climax, he was shot by a sharpshooter atop the mizzenmast of the Redoubtable the musket ball penetrating his left shoulder, piercing his lung and breaking his spine.

As he lay upon the deck in great pain surrounded by anxious staff he muttered: “They have done for me Hardy, my back is shot through.” He knew he was dying and told the ship’s surgeon William Beatty – there is nothing you can do for me.

Pausing for a moment to advise a young Midshipman on how best to use the tiller he was taken below decks to the cockpit where he was laid out with others who had had been wounded in the service of their country in a scene the ship’s Chaplain Alexander Scott described as a butcher’s yard. It was certainly no place of peace to end a life cut short at the moment of its greatest glory.

Less than an hour after Nelson was shot the Redoubtable and Santissima Trinidad succumbed followed shortly after by Villeneuve on the Bucentaure who was taken into captivity. The sight of the Bucentaure raising the white flag had a devastating effect on French morale.

The vanguard of the Franco-Spanish Fleet which had initially sailed away from the fighting until being ordered back by Villeneuve now fired an indiscriminate broadside before sailing away once more. Others tried to disengage and make their escape but with little success.

Sporadic fighting continued but the outcome of the battle was no longer in doubt and as the enemy ships surrendered one after another it became increasingly evident that the victory was total. For the loss of no ships, 458 men killed and 1,208 wounded the powerful Franco-Spanish Fleet had been destroyed and the threat to British liberty eradicated.

Combined the French and Spanish had lost 22 ships sunk or captured with many of those that escaped damaged beyond repair and 3,053 men killed, 2,438 wounded, and a further 8,000 taken prisoner.

But the nightmare had not ceased for those who had been fortunate enough to escape the carnage as a violent storm now wreaked havoc with the survivors as many of the burned and crippled hulks sank drowning more than 3,000 prisoners locked below decks and the British had to abandon all but four of their prizes.

Throughout, Nelson informed of events had continued to issue instructions until too weak to do so but when told by Hardy of the scale of the victory he breathed a sigh of relief and remarked: “Thank God, I have done my duty.”

At 4.30 pm he died, his last recorded words – God and Country.

To preserve Nelson’s body, it was placed in a casket of brandy which was then lashed to the mainmast and placed under armed guard.

The victory at Trafalgar was greeted with relief and no little joy though the celebratory spirit was dampened somewhat by the news of Nelson’s death.

Some suggested that it had been too high a price to pay but then is any price too great for the life of a nation? When Emma Hamilton was told of her beloved Horatio’s death, she was quite literally shocked into silence later writing that she was unable to speak, utter a sound, or even shed a tear for many hours.

Nelson was accorded the honour of a State Funeral in a display of national mourning never seen before and only rarely since.

On 8 January 1806, following five days of public mourning Nelson’s body was taken from its resting place at Greenwich Hospital and accompanied by numerous vessels of all kinds carried down the River Thames in a Royal Barge cloaked in black velvet and decorated with ostrich feathers to Westminster as thousands viewed the magisterial procession from the riverbank and the bridges it passed under.

Taken to the Admiralty Building where it remained overnight the funeral cortege continued to St Paul’s Cathedral the following day as it seemed the entire city turned out to watch.

The coffin which had been placed on a carriage designed to resemble the Victory and adorned with battle trophies had both a military escort and so many principal mourners that the procession took many hours to make the short journey to St Paul’s.

But for all the ceremonial fanfare and expressions of deep sorrow the scandal of his domestic affairs had barely diminished and so there would be no formal Royal representation at the funeral. Indeed, when the Prince of Wales requested permission to attend, he was informed that he could only do so in a private capacity.

Similarly, Emma Hamilton was refused permission to attend the funeral, her status as an adulterer deemed morally repugnant and a stain on the reputation of the deceased.

The interior of St Paul’s Cathedral was decorated with reminders of Nelson’s career – his trophies, uniforms and awards with captured French and Spanish battle flags hanging from the rafters.

The ceremony was to last four hours and long into the night before the coffin placed in a marble tomb that had once been intended for Cardinal Wolsey was finally lowered into the crypt of the Cathedral. The final words spoken: “The hero, who in the moment of victory, fell covered with immortal glory.”

The glory it seemed did not extend to Emma Hamilton, the woman he loved. She had refused to countenance divorcing her husband while he still lived but since his death had been excitedly contemplating her marriage to Nelson. But it wasn’t to be, he would not be her husband and for that she would pay the price.

Ignored by the Government despite Nelson’s request in his Will that they ‘take care to maintain her rank in life’, Emma always generous to a fault quickly squandered the inheritance left to her by Sir William and by trying to maintain a status for herself and her daughter that she believed Nelson could be proud she was soon heavily in debt.

Still, she continued to petition the Government for support but the publication of letters between her and Nelson outlining the details of their affair only created further scandal.

By the summer of 1812, she was in prison for debt.

Fearing that further creditors lurked in the shadows upon her release she fled with her daughter to France. Impoverished, weak through illness, and abandoned by her friends she turned to drink as her only solace dying in Calais on 15 January 1815, aged 49.

Following her mother’s death Horatia returned to England in secret to live with her aunt.

Ignoring her father’s wish that she should forever be known as Nelson, Horatia married the Reverend Philip Ward and lived a quiet life in Norfolk as the mother of 8 children refusing all opportunities to benefit from her famous parentage. She died on 6 March 1881, aged 80.

Napoleon Bonaparte did nothing to facilitate the release of Admiral de Villeneuve (who had been permitted to attend Nelson’s funeral) despite his frequent requests for him to do so and in the end, he was forced to make his own way back to France where Napoleon refused to receive him or answer his letters. On 22 April 1806, he was found dead in his hotel room having been stabbed multiple times. The verdict was suicide.

In recognition of Admiral Lord Viscount Nelson’s achievements in 1843 the 170-foot Nelson’s Column was unveiled in Trafalgar Square, London, where for many years it would dominate the city’s skyline. – Britain’s greatest monument to Britain’s greatest hero.

Share this post: