Night of the Long Knives

Posted on 26th July 2021

On 30 January 1933, Adolf Hitler was sworn in as Chancellor of Germany.

He had not been elected to the post, indeed his National Socialist German Workers’ Party or Nazi Party, had seen their share of the vote decline in the recent election; rather his appointment had been engineered by a previous Chancellor Franz von Papen in an attempt to prevent his great rival General Kurt von Schleicher from forming a new Administration.

It took a great many hours of argument on his part, to convince the ageing Reich President Paul von Hindenburg who despised Hitler as that coarse little Corporal to appoint him Chancellor, but it would only be at the head of a Coalition Government he told him, the real power would lie elsewhere. Having eventually got his way the aristocratic and vain von Papen was delighted, there was no doubt in his mind that he could easily manipulate the common and ill-educated Hitler, and that he would be little more than putty in his hands.

Hitler may now be Chancellor but there were to be few Nazi Party members at the cabinet table and so unable to form a majority in the Reichstag or even in his own Administration he still appeared to be some way from having his hands on the real levers of power. It seemed as if his time as Chancellor would be short-lived which is exactly what von Papen intended.

All this was to change however when on 27 February 1933, the Reichstag was set ablaze, and a young Dutch communist Marinus van der Lubbe was captured at the scene and charged with arson. Hitler was quick to seize the opportunity of the Reichstag fire to announce he had uncovered a communist conspiracy to overthrow the Government and declare a state of emergency.

The fear of communist revolution in Germany was a very real one with the example of the Roter Republik in Bavaria and the Spartakist Revolt in Berlin, both of which had to be crushed by force, still fresh in the memory. The communist Party was also the third largest in Germany regularly polling around 25% of the vote.

So, when on 23 March, Hitler went to the Reichstag to demand the passage of an Enabling Bill that suspended the constitution for a maximum of four years and permitted the Government to rule without recourse to established laws or to seek approval from the German Parliament it met little opposition.

At the stroke of a discarded match von Papen’s strategy had unravelled and Hitler was now firmly in control. He could now re-build Germany as he saw fit and return her to the greatness, he believed it was his destiny to achieve.

Over the next few months, he proceeded to suppress the communists, abolish the trade unions, arrest and imprison his political opponents and systematically eliminate all domestic opposition. But one threat still remained, and it came from within the Nazi Party itself.

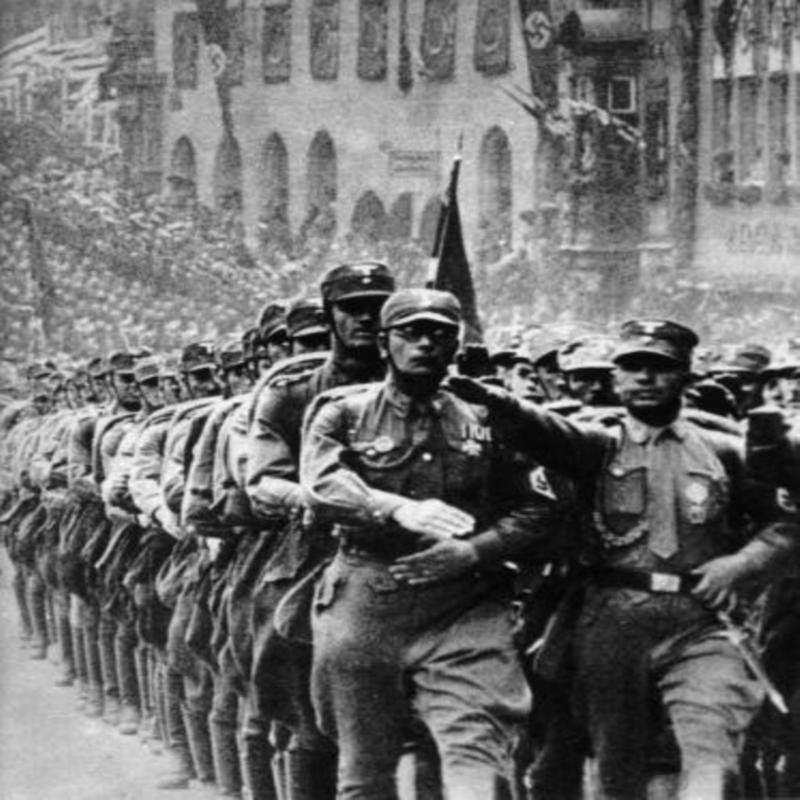

The Sturm Abteilung better known as the SA or Brown-shirts were a paramilitary organisation created to intimidate and bully opponents of the Nazi Party and were to play a pivotal role in their rise to power. They confronted communists and socialists on the streets of German towns the length and breadth of the country, broke up rallies and meetings, and marched through town centres in shows of force intended to cow local populations but with Hitler’s assumption of power their continued value became a matter of conjecture. they were to a legally constituted Government an embarrassment.

Yet by 1934, the SA numbered 4 million men and they had no intention of voluntarily disbanding. Indeed, it was rumoured they had an agenda all their own.

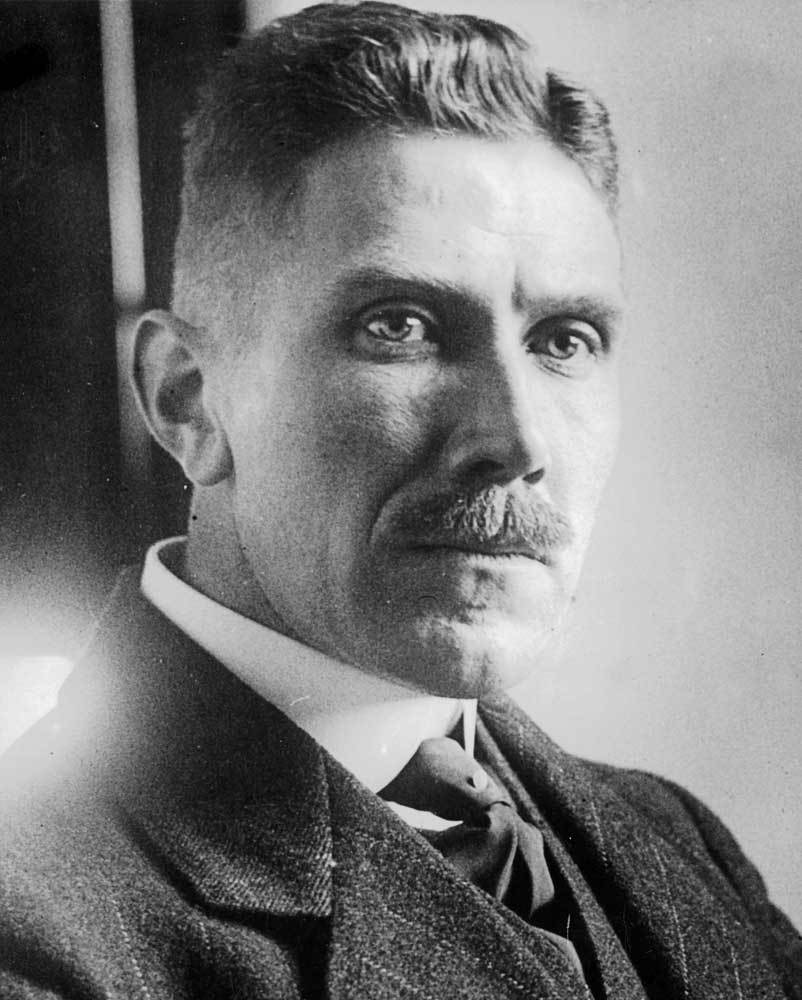

The SA was led by the charismatic war hero and one of Hitler’s oldest comrades Ernst Rohm, a brute of a man and a street brawler with the facial scars to prove it and an active homosexual as indeed many of the SA leadership were. He was also one of the few men who could refer to Hitler by his first name and who did not shirk from disagreeing with him, telling it to him straight and even chastising him on occasions. Hitler was even known to defer to him in discussions and it seems more than likely that he not only admired but was a little afraid of Rohm. He was also extremely ambitious.

Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor was known within Nazi circles as the First Revolution, Rohm and the SA leadership now began to call for the Second Revolution or the implementation of those socialist policies outlined in the Nazi Party’s 25 Point Programme. Specifically, the nationalisation of the big corporations, profit sharing in large industrial enterprises, the expropriation and redistribution of land and most incendiary of all the abolition of the regular army, the dismissal of the Officer Corps and the creation of a People’s Army which would have at its core those already serving in the SA.

At the very least, Rohm demanded that his Brown-shirts be incorporated into the regular army. As the army was at this time restricted by the terms of the Versailles Treaty to a maximum of only 100,000 men this would have led to it being swamped and effectively taken over by Rohm.

Hitler had never intended to implement any of the socialist policies contained within the Nazi Party’s 25 Point Programme, they had simply been designed to keep the more radical members on board and provide the Party with a policy platform that went beyond merely the acquisition of power for its own sake and with which to campaign on in elections.

In any case, he needed the support of big business and had been busily wooing the likes of Krupp’s and I.G Farben for some years. More significantly perhaps, he sought the acquiescence and support of the army in his takeover of power, for though small in number it was a well-drilled and well-trained formation with an experienced and highly skilled Officer Corps. He needed them if he was to achieve his territorial and geo-political ambitions. What he no longer needed was 4 million drunken, ill-disciplined street-brawlers.

On their part, the army had demanded that he curtail the ambitions of Rohm and traduce the effectiveness and power of the SA.

Rohm however was a powerful man and despised though they were by the regular army the SA could probably seize power if they wished to do so. More to the point, Hitler appeared increasingly incapable of wielding effective control over them they were running extortion rackets and prostitution rings and continued to be responsible for widespread violence.

It seemed as if the Nazi takeover of power had merely provided them free licence for their activities.

For Hitler however the problems went beyond this, he was always a man for whom loyalty was paramount and he was loathe to act against old allies and especially Ernst Rohm who was perhaps as close as anyone could get to being considered a friend.

In 1925, an elite group had been formed from within the SA that was to serve as Hitler’s personal bodyguard, the Shutzstaffel or SS. By 1933, they were the responsibility of Heinrich Himmler and his sinister deputy Reinhard Heydrich both of whom were every bit as ambitious as Rohm and saw him as a direct threat to their own power and they worked assiduously on Hitler’s always heightened sense of paranoia.

They told him that they had uncovered a plot to depose him, that Rohm was intending to use the SA to seize power by force, and that if he did not strike first then he would be powerless to resist him. Still, Hitler remained reluctant to act.

In February 1934, in private discussions he told Rohm that the SA would never replace the regular army in Germany and much to everyone’s surprise Rohm appeared to agree. It seemed for a time at least that the crisis had been nipped in the bud but by April, Rohm had embarked upon a nationwide speaking tour where he addressed massed rallies of SA Storm-troopers telling them that "the SA is the National Socialist Revolution." He appeared to be speaking as if he was a leader-in-waiting, providing all the ammunition that Himmler and Heydrich required.

On 4 June Hitler held a further meeting with Rohm where referring to him as his oldest friend they discussed those issues that still remained outstanding with regards to the future of the SA. The meeting was cordial with Rohm announcing that he intended to take a vacation and would order the SA to stand down for the month of July.

Later that day he ordered the SA leadership to gather at the spa resort of Bad Wiessee near Munich.

To his enemies, and he had many, it seemed that the leadership of the SA were gathering to organise a coup. In fact, it was to be nothing more than a homosexual orgy away from the public gaze. Nevertheless, Himmler and Heydrich were to play it for all it was worth to stoke up the anger against Rohm and press home the urgent need for action. In the meantime, the pressure was ratcheted up a notch.

On the 17 June, Franz von Papen under pressure from Heydrich gave a speech denouncing the SA for providing succour to the Party’s enemies. He told his audience: “We have not experienced an anti-Marxist revolution in order to put through a Marxist programme." He then persuaded President Hindenburg of the urgency of the situation insisting that he must meet with his Chancellor, no easy task given his personal loathing of the Bohemian Corporal. Nevertheless, on 21 June, Hitler was summoned to a meeting with the President of the Reich.

The old man was by now very frail, confined to a wheelchair and clearly senile but he was still able to curtly inform his Chancellor that if the problem with the SA was not resolved to his satisfaction, then he would dissolve the Government, declare martial law, and invite the army to run the country. Hitler now had little choice but to act.

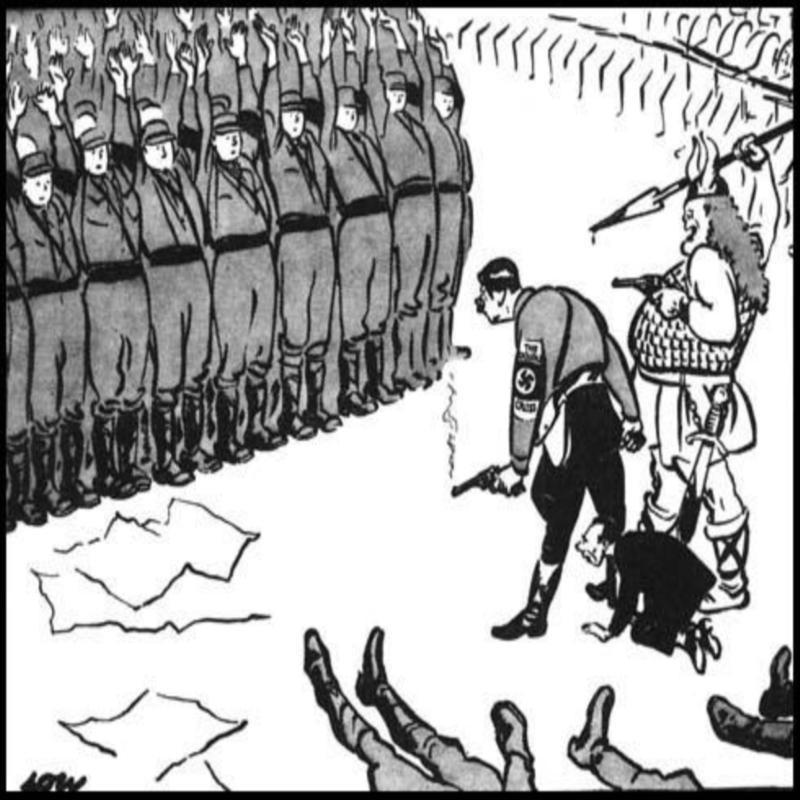

Following discussions behind closed doors with Himmler and Heydrich, Hitler called a meeting of the Nazi inner-circle where he informed them that he had uncovered a plot by the SA to overthrow the Government. These traitors would be dealt with by his personal bodyguard the SS he told them, and the arms for doing so would be provided by the army which would remain confined to their barracks throughout unless called upon. He would lead the operation himself while Hermann Goering would deal with the conservative opposition in Berlin.

Upon his arrival in Munich Hitler immediately arrested the leading SA man in the city, accused him of disloyalty and in a public ceremony stripped him of his insignia while Ernst Rohm just a few miles away in Bad Wiessee remained oblivious to what was going on.

On the early morning of 30 June Hitler accompanied by soldiers of the SS and with the Deputy Fuhrer Rudolph Hess at his side arrived at the resort where the SA leadership were staying. Once the hotel had been surrounded and the staff ushered into a room, Hitler entered and armed with a pistol hurriedly made his way to Rohm’s room where bursting in he ordered the SA leader dragged from his bed and out of the arms of his male lover.

Standing naked before Hitler, Rohm then had to endure a torrent of abuse before the Fuhrer ordered him taken away. Roughly dealt with he was unceremoniously carried off to Stadelheim Prison just outside Munich. Hitler hadn’t been so generous with another SA leader he had discovered in the act of having homosexual sex with a young man. He had them both executed on the spot.

Despite everything Hitler could not bring himself to order the death of his old friend and was inclined to grant him a pardon but under pressure from Himmler, Heydrich and Hermann Goering he finally conceded that Rohm had to die but he hoped that as an Officer and a man of honour he would take his own life.

He told his captors to provide him with a pistol with a single bullet but languishing in his cell Rohm had no intention of doing Hitler’s dirty work for him. Presented with suicide as an alternative to execution and public disgrace he replied: "If Adolf wants me dead then let him do it himself.”

Fifteen minutes later two Officers, one of whom was Theodore Eicke the future Commandant of the Dachau Concentration Camp, entered Rohm’s cell and shot him dead. His last words were: "Mein Fuhrer! Mein Fuhrer!"

A propaganda campaign now blanketed the country condemning the SA as traitors. Its leaders had been plotting a coup, they repeated time and again and those associated with the organisation could no longer be trusted.

Once the public face of the Nazi Party they were now jeered at and abused in the streets. Also, afraid for their own lives members now began to leave the SA in droves. Its power had been broken.

Meanwhile in Berlin, Hermann Goering had also been busy as he and others elsewhere in Germany now took the opportunity to dispose of those they considered enemies of the Nazi Party or felt had offended them in the past; among those murdered was Gustave Ritter von Kahr who as State Commissioner of Bavaria had crushed Hitler’s Putsch in Munich, General von Schleicher who had been Hitler’s rival for the Chancellorship who was shot along with his wife, Gregor Strasser, Hitler’s only remaining rival within the Nazi Party itself and Father Bernhard von Stempfle who it was thought knew too much about Hitler’s past and his personal life; Erich Klausener the leader of the right-wing opposition Catholic Action Party was another victim and assassins were even sent to murder Franz von Papen but he was not in his office at the time so they shot dead his secretary instead. One young man, a promising cellist, was dragged from his family home and shot because he was unfortunate enough to share the same surname as a prominent anti-Nazi. His body was later returned to his family along with a letter explaining that he had died in a road accident and with express orders not to open his coffin.

Hitler tried to cover up the events of what was to become known as the Night of the Long Knives, but it was impossible. On 13 July, in a speech to the Reichstag that was broadcast to the nation he tried to justify these extra-judicial murders:

"If anyone reproaches me and asks me why I did not resort to the regular courts of justice, then all I can say is this, in this hour I was responsible for the fate of the German people, and I thereby became the supreme judge of the German people. I gave the order to shoot the ringleaders in this treason, and I further gave the order to cauterise down to the raw flesh the ulcer of this poisoning of the wells in our domestic life. Let the nation know that its existence – which depends on its internal order and security – cannot be threatened by anyone. Everyone must know for all future time that if he raises his hand to strike the State then death will be his lot.”

The Nazi Government gave the official death toll for the Night of the Long Knives as 61 executed and 13 killed whilst trying to escape. More recent research however has suggested that the real figure for those killed might be as high as 1,200.

There is little doubt that in the months preceding the Night of the Long Knives Ernst Rohm had been flexing his not inconsiderable muscle and had been manoeuvring for a greater role in Government for himself and his brown-shirted supporters, but little evidence has ever been uncovered that they were plotting a coup.

Soon after the events of 13 July the Nazi’s passed a law retroactively legalising the murders but few people could any longer be in any doubt that what had been viewed as the authoritarian, but legally constituted Government of Germany had become a regime of gangsters and murderers.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous, Modern

Share this post: