Omaha Beach

Posted on 24th August 2021

Tuesday, 6th June 1944 would be D. Day, the start of Operation Overlord the Allied invasion of Nazi Occupied Europe. It had originally been intended for the day before but storm conditions at sea, high winds and poor visibility had forced a postponement, but it could not be delayed indefinitely however, with the Armada ready to sail and the required high tides and full moon imminent any further delay could only lead to outright cancellation.

The atmosphere at SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) was then understandably tense and opinions as to a course of action sharply divided, so it was with some relief that General Dwight David Eisenhower, the man burdened with the responsibility received the report of his Chief Meteorologist that the coming few days would present a brief window of improved conditions, but improved did not suggest good and it certainly did not mean calm.

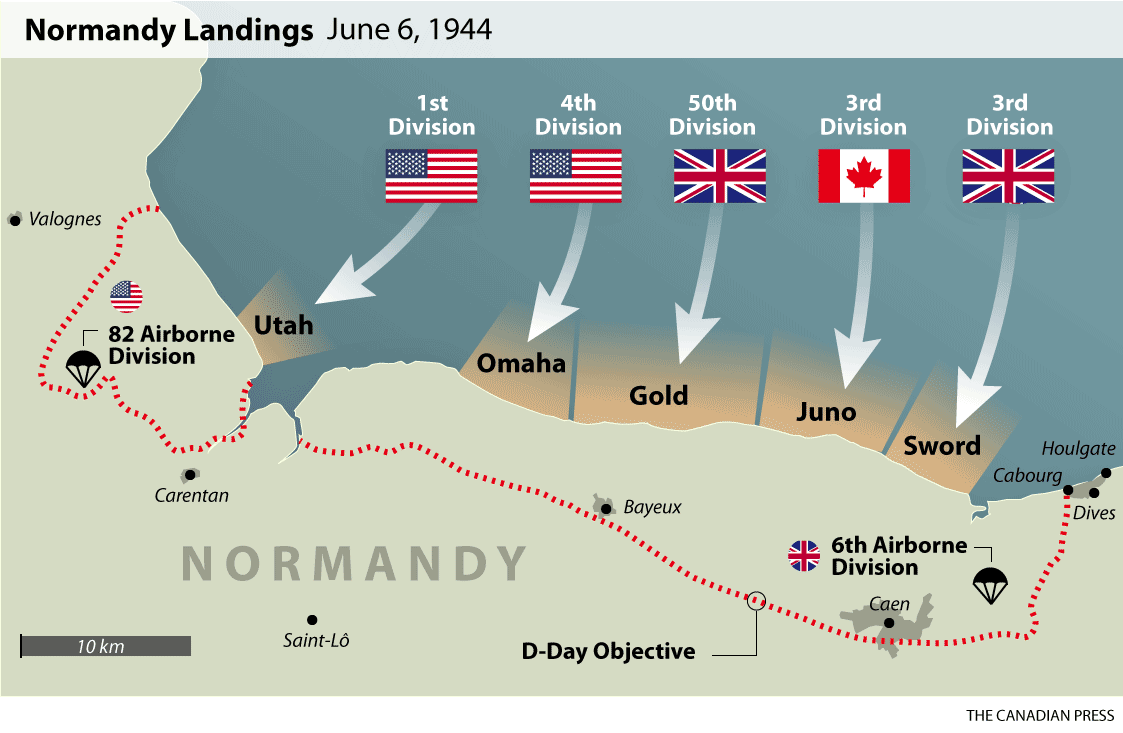

The plan was for a massive Armada of 5,000 vessels with 11,000 planes providing aerial support to land 156,000 men on 5 designated beaches along the Normandy coast. One of these landing sites was codenamed Omaha, a five mile stretch of crescent shaped beach situated between the villages of Vierville-sur-Mere and Coleville-sur-Mer with sheer cliffs to both its left and right and high bluffs in front. It was by far the least promising of the landing sites, but it had to be taken to link up with the British at Gold Beach and with their fellow Americans on Utah Beach.

An Allied invasion of Fortress Europe was hardly unexpected so the possibility of gaining any strategic advantage from the assault was already lost but there was still the opportunity for operational surprise – where would the invasion come, where exactly would the landings be made?

The most obvious place was the Pas de Calais the shortest distance across the Channel from England and great efforts of deception were undertaken to convince the Germans that this was indeed the case. Certainly, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, the legendary Desert Fox and man responsible for fortifying the so-called Atlantic Wall thought so and he focussed his attention on just that region but never to the level of neglect elsewhere that had been anticipated and planned for.

Despite his frustration at being denied a battlefield command since his return from North Africa, Rommel approached his new remit with gusto trawling over maps, studying blueprints and making regular tours of inspection. He also pondered at length the best strategy to be adopted in the event of any invasion and was convinced that it had to be confronted where it landed, on the beaches, and when the enemy would be at his most vulnerable.

The German Commander in the West Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt disagreed however, preferring instead a defence in depth. The argument between two of the most respected Senior Officers in the German High Command would fester and prove increasingly divisive particularly over the distribution of the Panzer Divisions which were held under Hitler’s personal command, and though a compromise would eventually be reached it did little to smooth relations or create a coordinated response.

With his plans to drive the enemy back into the sea thwarted Rommel remained determined instead to create killing zones on the shoreline too costly in human flesh and blood for the Allies to endure.

The troops assigned the task of storming Omaha Beach were men of the 1st Infantry Division, the ‘Big Red One’, veterans of the campaigns in North Arica and Sicily and the 29th Infantry Division men barely out of their teens as yet untried and untested - a deliberate fusion of the old and the new, the careworn and the cynical with the young and the enthusiastic.

Now after months of intense training and preparation the moment of decision had come; their precise destination remained a mystery to most and rumours were rife but pledged to silence they were whispered rather than shouted. So aboard the ships many had already been on for some days’ time was spent reading, writing letters home, attending church service, playing cards or simply resting and thinking of what lay ahead. Before they departed, they heard a message from General Eisenhower:

Soldiers, Sailors and Airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force!

You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. The hopes and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you. In company with our brave Allies and brothers-in-arms on other Fronts, you will bring about the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazi tyranny over the oppressed peoples of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world.

Your task will not be an easy one. Your enemy is well trained, well equipped and battle-hardened. He will fight savagely.

But this is the year 1944. Much has happened since the Nazi triumphs of 1940-41. The United Nations have inflicted upon the Germans great defeats, in open battle, man-to-man. Our air defences have seriously reduced their strength in the air and their capacity to wage war on the ground. Our Home Fronts have given us an overwhelming superiority in weapons and munitions of war, and placed at our disposal great reserves of trained fighting men. The tide has turned! The free men of the world are marching together to victory.

What they didn’t hear was the other short note the General had penned and kept on his person:

“Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based on the best information available. The troops, the Air, and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone.”

In the event it never had to be broadcast.

Amazingly the 5,000 ship Armada, the largest sea-borne operation in the history of the world went virtually undetected in the narrow straight that separated England from mainland Europe. Field Marshal von Rundstedt was far away at his Headquarter in Koblenz on the Rhine oblivious to the invasion that was imminent while Rommel had returned to Germany to attend his wife’s birthday party. It seemed then, that the many acts of deception had worked beyond the protagonist’s wildest dreams and little, if any, attempt was made to hinder the Armada’s deployment off the French coast, so as the sun rose and the mists cleared that dreary summer morning the surprise was almost total.

At 05.50 on 6 June 1944, after 1,738 days of war 138 Allied ships of various types some 13 miles out to sea began to bombard German coastal defences. Around the same time bombers of the Royal Air Force followed soon after by those of the United States Army Air Force began flying the first of some 13,688 sorties against enemy communications, transport hubs, and rear areas.

Meanwhile, in a heavy swirl, buffeted by six-foot waves, 18 mph winds, and weighed down by 60 pounds and more of equipment troops began descending scrambling nets into waiting landing craft where tightly packed, weakened by fear, tormented by thoughts of death and distracted by memories of home the squally damp conditions only added to the sense of foreboding.

Many of the men green to the gills were violently sick vomiting into their helmets while others more able to keep their breakfast where it belonged used theirs to bail out the craft just to keep it afloat. Even so, ten landing craft in that First Wave would be abandoned at sea swamped, holed below the waterline or destroyed by enemy fire.

Forced to take a circuitous route to avoid the six 155 mm guns located atop Pointe du Hoc a few miles further down the coast that could target the landing craft as they approached the shore the troops hunkered down cold and wet for what seemed an eternity. In the meantime, a Ranger Battalion undertook the perilous task of scaling the cliffs with rope ladders and grappling hooks to eliminate the threat only to find no guns (they had in fact been moved further inland the previous month) only telegraph poles. The 500 men still in their boats who had not participated in the initial ascent would later be landed elsewhere on Omaha Beach to telling effect.

The Pointe du Hoc fiasco would not prove the only failure of intelligence that day, the defences at Omaha were believed to be manned by just 1,000 troops many of whom were barely motivated Russian volunteers and aged Reservists but these had in fact been reinforced the previous March by the 352nd Infantry Division veterans of the Eastern Front; and they were well dug-in behind barbed wire and minefields in 15 separate strong points or Resistance Nests with 35 pill boxes connected by tunnels and defended by heavy machine guns, light artillery pieces and anti-tank weapons. And at Omaha, as elsewhere that day there would be no free ride to the beach:

Four lines of obstacles had been constructed in the inner-tidal zone, the area of shore that is under water at high tide; 270 yards out from the high water line were 200 Belgian Gates, heavy steel fences some 2 metres high with mines attached; at 235 yards out was a continuous line of sharpened logs pointing seaward each third one armed with a mine; at 202 yards out were a series of ramps also armed with mines which were designed to tip over and capsize those landing craft that ran onto them; at 160 yards out were numerous hedgehogs, X-shaped anti-tank obstacles with explosives attached - all this had to be encountered and overcome before the troops even disembarked.

Neither was it ever intended for the troops to storm Omaha Beach unsupported but few of the amphibious tanks assigned to provide fire support made it ashore, the rest were swamped in the heavy seas and their crews drowned while those that did with no radio communication and unable to coordinate their fire proved largely ineffective.

As the ramps came down on the landing craft many men, aware they would be targeted, chose instead to exit over the sides. Some craft also stopped too far out to sea forcing the shorter men to inflate their life preservers merely to stay afloat while some who had fitted them incorrectly tipped upside down and submerged, drowned.

Raked by machine gun fire the landing craft quickly became death traps as the men who abandoned them in haste blundered into mines or were shattered by the shellfire that now peppered the beach. Many did not make it out of the sea their bodies left to bob in the water or washed up with the surf. Others lay wounded on the beach unable to move waiting to be drowned as the tide came in. Army medics did what they could, but they were no less vulnerable to enemy fire than anybody else.

The survivors who made it across the almost 400 yards of open beach huddled behind a low shingle wall where wet, cold and uncertain what to do some nervously lit cigarettes while others tried to unclog the sand from their rifles. In the meantime, engineers worked to clear the beach of mines and any other obstacles incurring almost 50% casualties as they did so.

The Second Wave that landed fared better but only by comparison with the First and to General Omar Bradley, commanding U.S ground troops witnessing events on Omaha from a destroyer moored offshore it appeared the landing had failed and he more than once considered cancelling any further assault and withdrawing the troops already pinned down.

Seeing little on the beach other than the detritus of war and dead Americans the Germans felt victory was already theirs and had they counter-attacked at that moment they would almost certainly have driven the invaders back into the sea vindicating perhaps Rommel’s preferred strategy; but regardless of the carnage no hands had yet been raised, no white flag was visible and those Americans who had taken shelter behind the shingle wall were beginning to fire back. Bradley taking his cue from a number of vessels which had already done so ordered others to risk mines and the fire of shore batteries to close within a few miles of the beach and provide big gun support. It was gratefully received.

Among those who landed with the Second Wave was Brigadier-General Norman ‘Dutch’ Cota the highest-ranking Officer to engage in combat on D. Day who immediately began to bring some order to the chaos. Finding himself amongst a unit of Rangers relocated from Pointe de Hoc he ordered an advance from the shingle wall. Upon learning that some troops were refusing to budge he shouted:

“God damn it then Rangers, lead the way!”

It was a sentiment echoed elsewhere on the beach by Colonel George A. Taylor in command of the 16th Infantry Regiment who rallied his men with: “There are two kinds of people who are staying on this beach, those who are dead and those who are going to die. Now let’s get the hell out of here!”

Using Bangalore Torpedoes (an explosive charge set within a series of interconnected tubes) to blast through the defences they began to leave the relative safety of the shingle wall and advance up the bluffs first in small groups, then by the dozen, and finally by the hundred. Now forced to defend their own positions the Germans could no longer target the beach area with impunity as before and with ammunition running low their rate of fire began to slow. With the fresh troops being landed now able to cross the beach at pace through lanes cleared of mines and tanks able to provide the fire support so lacking earlier the tide of battle began to turn as one by one the pill boxes and machine gun nests fell or were abandoned in haste.

As the pressure intensified the German will to resist began to wilt and those who had not already surrendered were withdrawn further inland. By mid-afternoon the worst of the fighting was over, and a beachhead secured, but barely. The Americans had advanced little more than a mile from the beach, but it was enough. When reinforcements were landed the following morning (D.Day+1) it was so peaceful the troops could barely believe the rumours circulating of the intensity of fighting the day before. That is except for the discarded equipment, abandoned craft, burned out vehicles and bodies still floating in the water.

Accurate figures for the dead and wounded at Omaha Beach are difficult to ascertain with any accuracy but it is believed at least 1,300 Americans were killed and 4,500 wounded including 80% of the First Wave. German losses though fewer were not too dissimilar and were mostly the result of ship to shore bombardment.

Yet the Allied casualties on D. Day were far lighter than had been anticipated only 4,414 killed in all operations and 10,000 wounded. It was only on that slither of elongated sand known as Omaha Beach that the Allied High Command’s worst fears appeared about to be realised. That they were not was the result of German failure to exploit the opportunity presented them and the raw courage and perseverance of those American troops who held on amid the carnage that had threatened to engulf and overwhelm them.

Share this post: