Oswald Mosley: Britain's Fuhrer

Posted on 1st March 2021

Never entirely trusted by those who knew him or as charismatic as he liked to imagine the future Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley’s place in the national psyche far exceeds any political achievement on his part or indeed any influence wielded then or since; for it was his ambition to be Britain’s Fuhrer at a time when fascism appeared to be sweeping all before it and the spectre of his looming black-shirted presence that has burned so deep.

He was born on 16 November 1896 in Mayfair, London and as the address might suggest he was one of a privileged class, the governing class or so he though. Having served on the Western Front during World War One and then for ten years as a Member of Parliament for both the Conservative Party, the Labour Party he became an Independent. But then he was always a man for whom personal advancement always outweighed any human empathy or political conviction.

Following a standard upbringing of nannies, servants, and public school, in January 1914 he enrolled at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. Always a confrontational man he was to have his disciplinary problems, but all this was forgotten when by August of the same year Britain found itself at war with Germany.

Mosley was to have a good if somewhat truncated service record. He fought on the Western Front with the Queen’s Lancers in the early months of the conflict before volunteering for the recently formed Royal Flying Corps. He was to injure himself when he crashed his plane showing off to his family. The accident left him in great pain and with a permanent limp but despite his injuries he was to return to the trenches where he fought at the Battle of Loos in April 1915. Shortly after however, he was withdrawn from front-line service and provided with a desk job.

Ambitious, he was a young man in a hurry and following his discharge from the army eager to get involved in politics he used his social connections to secure the nomination as Conservative candidate for the Constituency of Harrow. He was elected as its Member of Parliament in the 1918 General Election aged just twenty-one. Four years later he left the Conservative Party over its role in the suppression of the rebellion in Ireland. A popular local MP who used his personal charm and war record to good effect he was to successfully retain his seat standing as an Independent.

In 1920, he married Lady Cynthia Curzon, or Cimmie, the daughter of Lord Curzon and in terms of his social standing it was a match made in heaven. It made some doubt his sincerity and none more so than his father-in-law - the marriage had elevated him into the upper-echelons of high society and made him a wealthy man.

The wedding was one of the social events of the year, but even though they were to have three children and portray themselves in public at least, as the perfect family, Lord Curzon’s fears were soon realised as Mosley had numerous affairs including with his wife’s sister and his mother-in-law.

Aware there was little future in remaining an Independent M.P, Mosley began looking elsewhere and in 1924 he joined the Labour Party that had just formed its first Administration and it was with the Socialists that he now believed lay not only the country’s future, but also his own. He had always considered himself a radical and a man of vision. He was a Conservative only by background not by nature he would say, now he would forge a career for himself as a man ahead of his time in the party of the future.

The first Labour Government survived only eight months but even, so Mosley was by now an enthusiastic supporter. In the General Election of 1929, Mosley challenged the future Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain for his Seat in Birmingham and was defeated by just 77 votes. It was a striking result and a defeat he blamed on the weather but not long after, on 21 December, he was returned as the Labour M.P for Smethwick in a by-election.

The Labour Party were re-elected to power in October 1929, and as a close friend of the new Prime Minister Ramsey MacDonald, Mosley expected to receive one of the High Offices of State. Instead, he was appointed Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, a position that did not even secure him a place in the Cabinet. He was furious and told MacDonald of his disappointment in no uncertain terms, but it appeared the high regard he had of himself was not always shared by others and that his reputation as a loose cannon and a serial philanderer unable to keep his trousers on went before him. Even so, to placate his ire he was given the task of coming up with a proposal to solve the problem of unemployment which was rising fast in the wake of the Wall Street Crash. He was excited at the opportunity to show that he was a man of ideas and one not afraid to make tough decisions. He dedicated himself to coming up with a plan that would see Britain come out of the economic depression that was stifling world trade and crippling global markets.

The Mosley Memorandum as it became known proposed high tariffs on imported goods and other protectionist economic policies, the nationalisation of large-scale industry, a massive programme of public works and job creation, and employer/worker co-operation. It was the first stirrings of the Corporate State but when it was presented to the Cabinet it was dismissed out of hand. Angered that the Cabinet was not even willing to discuss his proposals Mosley stormed out of the meeting and on 30 May 1930, he resigned his post.

For months he festered on the backbenches, where told by those across the political divide how well regarded his Memorandum had been he expected MacDonald to recall him to the fold. When this didn’t happen on 28 February 1931, he quit the Labour Party altogether. Not all were disappointed at his departure with many willing to express the view that he was a cad and a bounder who had never believed in anything other than himself. His cynicism they felt was best summed up in his remark, “Vote Labour, Fuck Tory.”

Mosley, never one to doubt his own political genius, didn’t view his resignation as a setback but as an opportunity. He firmly believed that he had the answers to the country’s problems and if the established political parties would not listen to him then he would form his own party and take his message directly to the people. So soon after leaving Labour he formed his own somewhat unimaginatively named New Party.

The Mosley Memorandum had been seen as a radical alternative to the sterile economic orthodoxy of the Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Snowden and the inertia of a government paralysed by crisis. Among those who had been signatories to it were a number of Labour M. P’s one of whom was the future architect of the National Health Service, Aneurin Bevan. He also had the support of the Miners’ Federation President A.J Cook and a great many Conservatives including the future Prime Minister Harold MacMillan. Mosley now confidently expected them to follow him, but few did.

He remained undeterred however, and upon receiving £50,000 in party funding from Lord Nuffield he established a party magazine under the editorship of the famous diarist Harold Nicholson and formed a party militia known as the “Biff Boys” under the command of the former England Rugby Captain, Peter Howard. He believed they were going places but were in fact heading for electoral oblivion. In the 1931 General Election the New Party contested 24 Seats and lost their deposit in all of them.

Following his political debacle, a depressed Mosley embarked on a tour of Europe looking for inspiration and was to find it in the charismatic leadership of the Italian Dictator Benito Mussolini. By the time he returned to Britain he had found a new way – Fascism.

Mosley now took a sharp lurch to the right and what remained of the New Party was disbanded and subsumed into his British Union of Fascists.

Always a greater admirer of Mussolini and his corporate vision of society than Adolf Hitler and his theories of racial purity, he now advocated an authoritarian centralised State with a strongman at the helm, and he knew exactly who that strongman should be – Oswald Mosley.

On 16 May 1933, Mosley’s long-suffering wife Cimmie died aged just 34, having earlier contracted peritonitis and following a botched operation. She had given up her own promising political career to support her husband and had turned a blind eye to his many affairs despite the great embarrassment they had caused her.

Mosley was distraught at his wife’s death or so it seemed; no one could be quite sure whether his grief was genuine as he was known to be having an affair with the already married Diana Guinness, a Mitford sister.

Three years later, on 6 October 1936, he was to marry her in the drawing room of Joseph Goebbels house just outside Berlin. The guest of honour was Adolf Hitler, from whom he received a silver framed photograph of the Fuhrer in familiar pose as a wedding present.

The death of Cimmie had not distracted Mosley from the business of politics for long and the formation of the British Union of Fascists or B.U.F was initially well-received in some quarters of the press and political establishment. Indeed, Lord Rothermere’s Daily Mail ran the headline “Hurrah, for the Blackshirts!” and held competitions to win free tickets to B.U.F organised events but as their rhetoric became increasingly anti-Semitic and hard-line support began to wane. Even so, in the two years following its formation membership peaked at around 50,000.

On 7 June 1934, the B.U.F held the biggest indoor rally in British political history at London’s Olympia. It was Mosley’s opportunity to stamp his mark on the national stage.

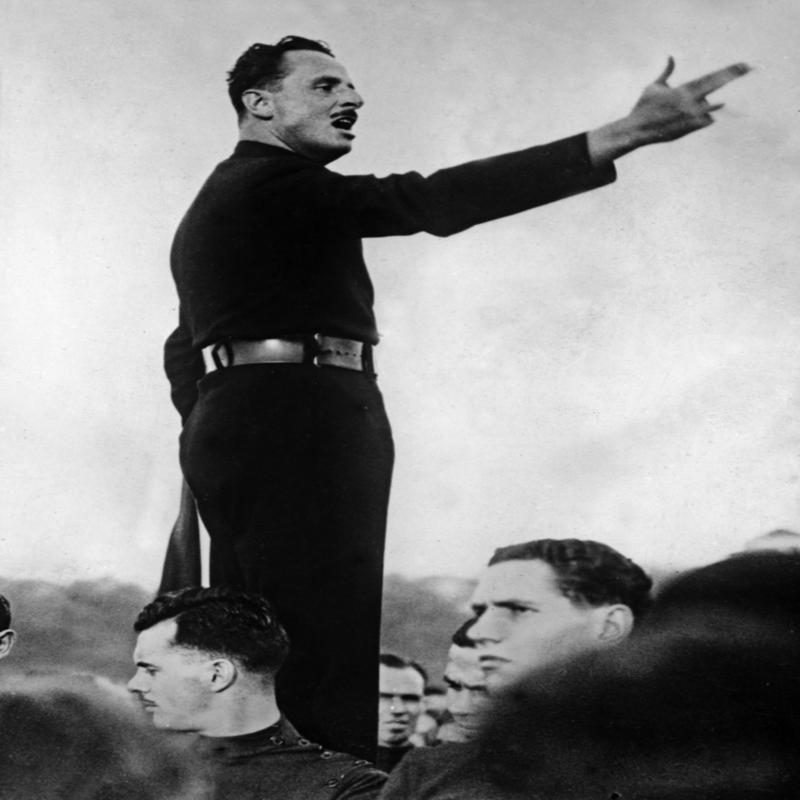

The event had been choreographed and fine-tuned to perfection as resplendent in his black uniform he arrived late to build up the tension and entered from the back of the hall and through the massed ranks of his supporters chanting his name but no sooner had he begun to speak than hundreds of people within the crowd began to shout, heckle, and hurl abuse.

Mosley ordered that the hecklers be removed, and they were forcibly so, dragged from the auditorium and brutally beaten up on the streets outside. Indeed, such was the level of violence used that what was intended to be Mosley’s showpiece rally had turned into bloody farce. The Daily Mail condemned the violence and withdrew its support, party membership began to haemorrhage, and political funding dried up, so much so that the B.U.F was unable to contest the 1935 General Election – Mosley’s finest moment had instead proven his nadir.

To try and revive the party’s fortunes Mosley decided to ratchet up the anti-Semitic rhetoric and take their arguments onto the streets with a march through a predominantly Jewish area of the East End of London. The B.U.F had always garnered sizeable support in the East End sometimes as much as 25% of the vote in local elections.

The march was designed to be a show of force and to re-establish Mosley, who tall and handsome always looked good in a uniform, and the B.U.F on the political stage. This would be his moment.

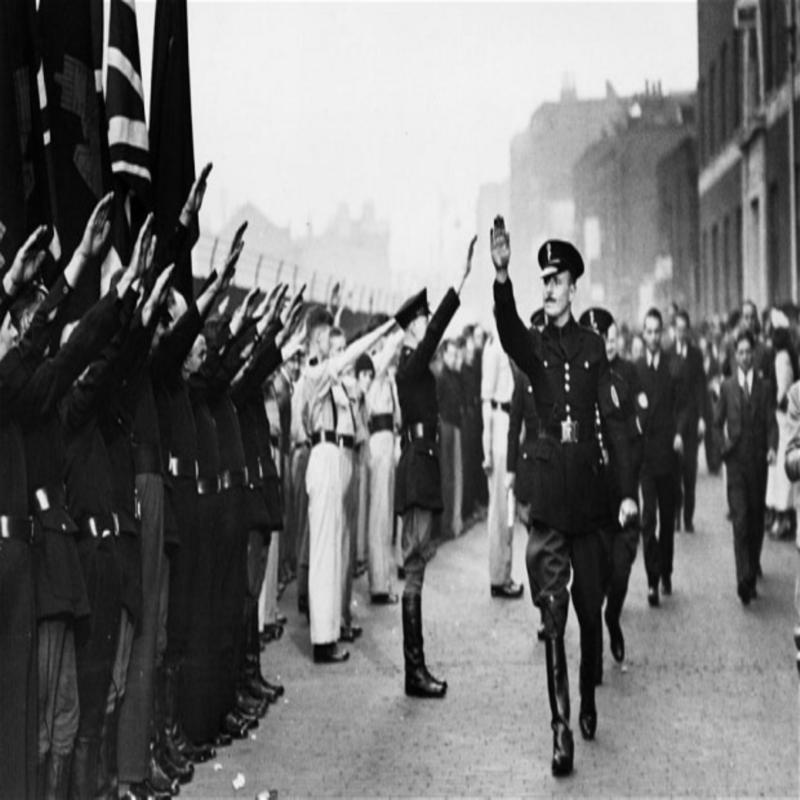

On 4 October 1936, 1,900 of Mosley’s Blackshirts assembled in the Borough of Stepney waiting to be addressed by their leader. Banners were unfurled and flags were raised as Oswald Mosley took the salute, but for all the passionate rhetoric and the heady atmosphere that prevailed very little happened. Prevented from entering the East End via Whitechapel by the police, Mosley decided to march down Cable Street. Forewarned, the people of the East End had barricaded the intended route of the march, and more than a 50,000 people had taken to the streets, Jews and left-wing activists for the most part but also dockworkers, labourers and local people who were always up for a fight with the police if nothing else.

Chanting “They shall not pass”, they had armed themselves and they were ready.

Mosley was ordered to wait while the police attempted to force a way through. More than 8,000 policemen had been mobilised to shepherd the march, but they were unable to control a demonstration that very quickly descended into a pitched battle. As the police tried to dismantle the barricades missiles began to be thrown, fights broke out, chamber pots were emptied onto policemen’s heads and marbles were strewn on the pavement bringing police horses crashing to the ground. For hours the police and demonstrators fought and all the time the increasingly restless Blackshirts waited for an order from their leader, their strongman, to march.

Around 4.00pm, some two hours after the march was supposed to have begun, Sir Philip Game, the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, aware that his force could no longer guarantee security suggested to Mosley that the intended march be called off to avoid bloodshed. After some dithering, Mosley agreed.

Many in the Blackshirt ranks were angry and dismayed at his decision especially among the more hard-line within the party, including William Joyce the future Lord Haw Haw. As far as he was concerned, they had been betrayed and at the very moment when decisive action had been required Mosley had crumbled. It had become apparent that he was not Britain’s very own Mussolini, after all. Forced to march under police escort to the West End and denied permission to hold a rally in Hyde Park the Blackshirts dispersed – defeated, demoralised, and humiliated.

Many of the more prominent members of the B.U.F now began to desert the party among them, Major J.F.C Fuller, military theorist and future follower of the Satanist Aleister Crowley; Arthur Gilligan, ex-England Cricket Captain; Ted “Kid” Lewis, the Jewish European Middleweight Boxing Champion who had taught the Blackshirts self-defence and was Mosley’s personal bodyguard; and any number of ex-M.P’s and Peers of the Realm.

The Battle of Cable Street, as it became known, had seen 84 people arrested and many hundreds injured. It had also forced the Government to act and later that year it passed the Public Order Act which banned the wearing of uniforms and required in future police permission to hold political rallies, demonstrations, and marches.

The fiasco of the abandoned march when Mosley was seen to shy away from confrontation saw a sharp decline in the membership of the B.U.F and by the end of 1936 its numbers had fallen to below 8,000 and Mosley was forced to axe hundreds of jobs simply to save money. One of those to go was William Joyce. He had been Mosley’s effective right-hand and a man who was tougher, more spiteful and more vicious than the leader could ever aspire to be, a real streetfighter. To many within the party he seemed the genuine article, not an aristocrat playing at dress up. They saw him as a rival for the leadership of the party. Mosley certainly thought so, that’s why he sacked him.

At the local elections of 1937 the B.U.F still polled around 25% of the vote in its East London strongholds but it was financially a busted flush and Mosley was reduced to spending much of his own personal fortune just to keep it afloat.

As conflict with Germany loomed ever larger Mosley embarked upon a tour of the country to warn against the dangers of a war that was the work of the Jewish Global Conspiracy and called for a peaceful negotiated settlement. With the devastation of the previous war still fresh in the public memory people were for a time willing to listen but as soon as the phoney war became a shooting one, Mosley’s political career was finished.

Despite ordering that all B.U.F members should do their patriotic duty and take up arms in defence of their country, on 23 May 1940, Oswald Mosley and his wife Diana endured the public humiliation of being arrested and imprisoned as potential traitors and fifth columnists. After a brief period in the cells, they were permitted to live together in a house in the grounds of Holloway Prison. It was less imprisonment than a form of public humiliation tempered by servants and a gardener.

Mosley was to spend his time in splendid isolation reading up on the great civilisations of ancient antiquity, pruning the roses and refusing requests to meet other imprisoned B.U.F members. His wife, Diana, remained unrepentant however and railed at the woeful treatment meted out to such a great man.

In November 1943, they were released into house arrest and went to live with their slightly embarrassed relatives.

Following the end of the war Mosley became the focus of constant media attention and any thoughts of a quiet retirement were dashed by his still overweening ambition. He could not stay away from politics for very long and he formed the Union Movement to campaign for a single unified European State. But by now he was more pitied and the subject of ridicule than he was either feared or hated. Few people any longer took him seriously and in any case his meetings were invariably interrupted and would end in chaos with Mosley being dragged from the podium and ushered away for his own safety. In 1951 he left England for France with the words: “You cannot clear up a dung-heap from underneath it.”

In exile he blamed the Jews for both the war and the ruin of his own political career. He was to spend the rest of his life campaigning against immigration and every time it became a hot political issue he would turn up like the proverbial bad penny.

In the wake of the Notting Hill Race Riots, he stood for Parliament in the General Election and lost his deposit. He claimed that the election had been rigged and took those responsible for the count to Court and lost there to.

In 1966, he returned to stand for the seat of Shoreditch and fared even worse gaining less than 4% of the vote.

The simple fact was that he was yesterday’s man. The man who had once aspired to be Britain’s Fuhrer was by now a marginalised figure, a maverick politician without a cause any longer worth fighting for.

Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley, 6th Baronet Ancoats, who had been ill for some time died at Orsay near Paris on 3 December 1980, aged 84.

In their obituaries the British press for the most part eulogised him as a visionary and one of the outstanding politicians of his generation, a lost leader in fact - how Sir Oswald would have enjoyed that.

Share this post: