Pilgrim Fathers

Posted on 9th March 2021

By the time of her death on 24 March 1603, the glory days of Queen Elizabeth’s reign were well and truly over. The defeat of the Armada all those years before may have been a blessed deliverance but the ruinously expensive war against Spain continued, overseas trade was in decline and a series of failed harvests saw unemployment increase and poverty stalk the land; with an aged and childless Queen on the throne who would come after her dominated discussion in the corridors of power, whispered though it might be. Her refusal to name a successor had led to great uncertainty and no little paranoia on the part of those responsible for ensuring a smooth and orderly transition of power.

The obvious successor was her nephew James VI of Scotland, but he would not be a popular choice and rumours of unrest and usurpation were rife. It was little surprise then, that the Tudor Police State encouraged denunciation with bribes, demanded compliance with menaces and kept the magistrates busy in hunting Jesuits, persecuting non-conformists and whipping paupers from the parish to parish, silencing dissent, and suppressing enemies of the state - so busy in fact that gibbets blighting the skyline became a morose and familiar sight.

Yet it had not always been so, Elizabeth’s reign had ushered in an unprecedented flourishing of the arts along with the spread of English power and influence around the globe as never before. A remarkable woman in so many ways, a star that shone bright beloved of a people who saw her as their own; Henry VIII’s bastard daughter had proven her worth and Good Queen Bess would be sorely missed but the years had not been kind, and few were sorry to see her go.

The twilight of Elizabeth’s reign had seen all pretence to religious toleration cease, the very idea “I will not make windows into men’s souls,” now merely a quote for the ages. Refusing to conform to the 1559 Act of Uniformity, the legal requirement to attend Church of England services was no longer thought aberrant behaviour to be rectified by force if necessary but a treasonable act that could be punishable by death.

Referred to as Recusants they were for the most part Catholics who refused to relinquish their ties to the old religion but there were also Calvinists who advocated a rigid interpretation of their own faith no less hostile to the Anglican Church of England. Known as Puritans they were few in number and unlike Catholics could not be accused of owing allegiance to a foreign potentate based in Rome, but they were nonetheless treated with suspicion and liable to both persecution and prosecution.

Genuine hope was expressed however, that with the Virgin Queen’s passing her successor James VI of Scotland would bring relief to those religious minorities subject to persecution and conciliatory words early in his reign had suggested as much. He was after all, both the son of the Catholic martyr Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots and a strict Protestant. Even so, he was no Puritan and though he revered his mother it was as the Divinely Appointed Monarch, he believed her to be not for her Catholicism.

The Guardians of Scotland responsible for the future King’s upbringing following the execution of his mother were determined to eradicate any trace of Catholicism in her son and he remembered all too well the harsh treatment he had endured at the hands of his tutors and others - the deprivations and humiliations, the verbal and physical abuse, the regular beatings. He had no love for the stricter kind of Protestantism and would come to hate all religious extremism in whatever form it chose to manifest itself. Even so, some believed that his mother’s milk and Biblical teaching would combine to create the toleration that had been so far lacking.

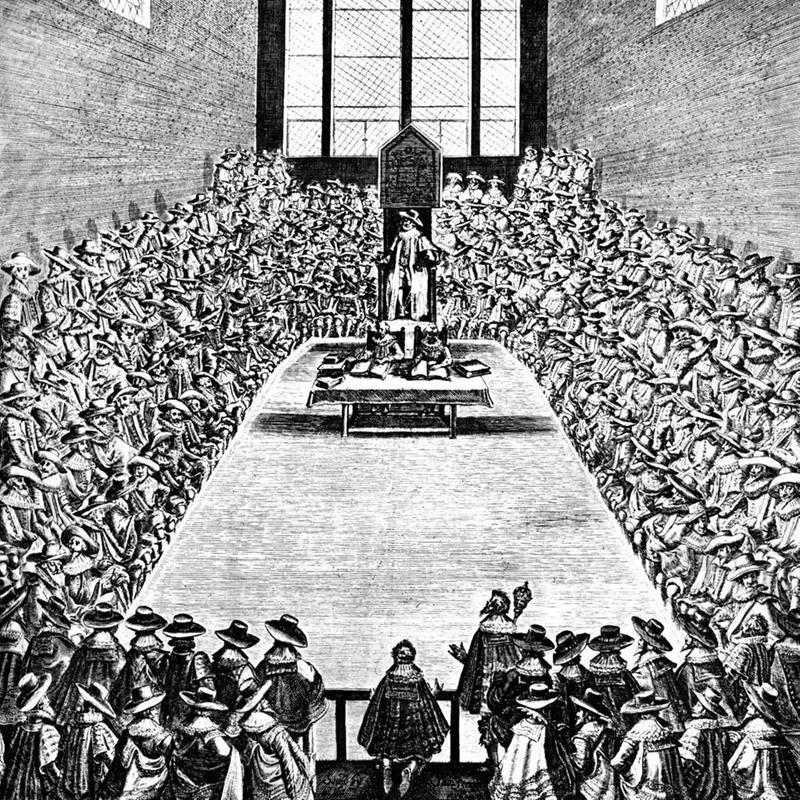

But it wasn’t to be, any hopes for greater compassion and a reconciliation of understanding were dashed at the Hampton Court Conference of January 1604, when it was made clear that religious toleration would not be extended to Roman Catholics and that the Puritans would be made to adhere to the 39 Articles of the Church of England.

It was perhaps testament to the King’s subtlety of approach and powers of persuasion that most left the Conference satisfied with its outcome for though James had conceded little he had at least appeared willing to listen and had also resisted demands from the Church to impose even heavier penalties upon Recusants. But this would all change the following year when a Catholic plot to blow up the entire English Establishment at the State Opening of Parliament along with the King and his immediate family was uncovered.

The Gunpowder Plot as it became known was not the first attempt on James Stuart’s life (fanatics had come close to assassinating him in Scotland also) and so despite it being an exclusively Catholic affair it effectively put all religious dissenters in the dock much to the anger of those who had played no part including most Catholics. But it should have come as no surprise that a King, or indeed a man, might be inclined to punish those who seek to murder him, and to restrain others whose beliefs are so irreconcilable as to incite such drastic a solution to the differences between them.

The English would never fall in love with their Scottish King in the way they had the Virgin Queen before him but in the immediate aftermath of the treasonous plot to assassinate him and the royal children James would for a short period at least bask in the warm sunlight of popular approval. It wouldn’t last of course, his character would see to that; his clumsy demeanour, coarse language, frequent drunkenness, open homosexuality, constant demands on the public purse and barely disguised contempt for parliament may have belied an acute political instinct and not inconsiderable diplomatic skill but it caused great offence to the Godly – the King was corrupt as his Church was corrupt. That runt child of Papist idolatry the Church of England with all its splendour and display, its stained glass, crucifix laden altar tables, tapestries, icons, worship of graven images and Latin Mass was an abomination. It’s Episcopacy and it’s Bishops simply intolerable - if the Puritans could find no relief in England, then they would go elsewhere for solace and redemption and the freedom to worship as they pleased - but where exactly?

Many of those who would later become the Pilgrim Fathers were from Nottinghamshire in the East Midlands one of whose leading members was William Brewster, Postmaster in the village of Scrooby who permitted the local Puritan congregation to meet in his home. It was indicative of how few they were that it was possible to do so. It was also no secret to the Bishop of Durham Matthew Hutton under whose religious jurisdiction Scrooby fell. Fortunately, Bishop Hutton was sympathetic to the Puritans plight believing that unlike the Catholics they could be persuaded to return to the Church of England, and he would write to the King in their defence, but when he died in 1606 to be replaced by Bishop Tobias Matthew attitudes hardened. He was determined to force these so-called ‘Separatists’ into line and the more outspoken among them were imprisoned while many others were penalised financially among them Brewster himself who was fined so heavily it brought him to the brink of ruin. His experience became an increasingly common one. It was written: “They could not continue in any peaceable condition but were instead hunted and persecuted on every side, so much that their former afflictions were as flea bites. Some were clapped in prison while others had their houses watched day and night. Many were forced to flee.”

In 1607 they decided to move to Leiden in the Netherlands a thriving commercial centre where they would not be hounded by the Authorities. Here they prospered in respect of work being readily available to them even if it was often menial and low-paid; but no longer liable to fines they were at least able to keep their money while being free to practice their faith and both publish and disseminate their teachings. As their later chronicler William Bradford would write: “Such was the true piety, a humble and fervent love of this people. Whilst they thus live together towards God and his ways they come as near the primitive pattern of the first churches as any churches of this latter time have come.”

Yet they remained very much a community within a community unable to break out into wider Dutch society even if they had chosen to do so which they did not. They found the morals of the Dutch to be even looser than those of the English they had so often complained about. It was an alien environment they would come to believe threatened their English identity and would overtime contaminate their faith. They feared for their children sensing they may be tempted away from the path of righteousness by as one of their number warned “evil examples into extravagance and dangerous courses.”

It was also the time of the ‘Twelve Year Truce’ an extended period of peace in the Dutch Provinces War of Independence from Spanish domination and the Puritans quite rightly feared their treatment should the truce end and Leiden fall into the hands of Catholic Spain.

They had to move on and soon some had already abandoned the community to return to England.

The New World was an obvious destination; it was far away and largely uninhabited except for native Indians with no recourse to civilisation:

“The place they thought of was one of the vast and un-peopled countries of America, which are fruitful and fit for living. There are only savage and brutal men present, just like wild beasts.”

There was also an English colony already established in the Americas at Jamestown in Virginia, a place of business and profit both profane and licentious that may have professed the Anglican faith but little more. The Puritans were possessed of a higher calling than mere vulgar commerce and any settlement they established would belong to God, a place where they could live a virtuous life for the benefit of their soul and not merely the frivolous blandishments of physical well-being. It was, they believed, the yearning of all God’s people to live in freedom according to their own lights so Jamestown then, was perhaps a place best avoided, but they were comforted by the fact it was English, nonetheless.

It would, however, be an expensive venture and a long perilous voyage that would be the cause of trepidation even in the hardiest of souls.

William Brewster would work hard over the next few years raising money for the planned migration and in trying to negotiate a land grant and charter from the King that would legitimise it and provide guarantees that would otherwise leave them vulnerable to exploitation from the more unscrupulous and powerful. In this he would fail but in 1617 one of his close associates John Carver did acquire a land grant from the Virginia Company based in London. Permission still needed to be sought from the King however, James who had no fondness for the strict Calvinism that had so blighted his youth was not inclined to do them any favours but despite adopting a hostile attitude he would not stand in their way on condition they recognised the Royal Supremacy and that of the Church of England while not seeking to formally establish a separatist Calvinist Church.

Raising the money for the voyage wasn’t easy however, the Puritans in Leiden may have prospered but they were far from rich and theirs was a small community with few friends. It appeared that their best laid plans would bear little fruit when in the early spring of 1620, Thomas Weston, a cloth merchant representing a number of businessmen seeking to break into the trans-Atlantic trade in fish and furs visited Leiden with a suggestion – would the Puritans be willing to engage in a commercial venture? Serving as agents of the Company of Merchant Adventurers of London was less than ideal but without the businessmen’s financial support their voyage could not be undertaken. They had little choice but to agree.

Brewster spent much of the year before departure in hiding having published a series of pamphlets critical of the King’s religious policies and the final preparations for the voyage were done by others.

Two ships were chartered for the voyage the smaller of which, the Speedwell, was hardly fit for purpose. It was already 45 years old, spent more time in dry dock than it did at sea and was more suited to coastal waters than it was an arduous Atlantic crossing. The other, the Mayflower, was a much larger and sturdier vessel, a three-masted merchant ship approximately 100 feet in length and 25 feet wide with three decks and a cargo capacity of 180 tons. She was also heavily armed with more than a dozen cannon of both light and heavy calibre with a fully stocked armoury of muskets, swords, pikes, breastplates, powder and ball. The threat posed by pirates, particularly Barbary Corsairs was a very real one and every precaution was taken against boarding and night attack.

In July 1620, those chosen for the voyage to the New World departed the Netherlands aboard the smaller cargo vessel Speedwell bound for Southampton in England. The tendency of the Speedwell to leak did little to inspire confidence in a community where the reluctance to embark upon any sea-crossing was evident and the excuses not to do so manifest and many.

In Southampton they met for the first time Christopher Jones, co-owner and Captain of the Mayflower, a rugged, straight-talking married man in his early fifties who was an experienced mariner having plied the trade routes of northern Europe and the Mediterranean for many years. He had never sailed to America before, he told them, but knew the Atlantic well from his time deep sea fishing and his many whaling expeditions.

Despite the little they had in common Brewster, Bradford, Carver and the other leading Puritans were to strike up a good working relationship with Captain Jones, the indispensable man if they were to have any chance of success in their great adventure.

They first set sail for the New World on 5 August 1520, but did not get far before the Speedwell sprung a leak, began taking on water and had to return to port for repairs. When a second attempt had likewise to be abandoned the decision was taken to leave her behind along with many of her passengers and crew.

On 6 September they set sail once more, a day one of the congregation Edward Winslow travelling with his wife Mary later recalled:

“Wednesday, 6th September, the wind coming east north-east, a fine small gale, released from Plymouth having been kindly entertained and courteously used by diverse friends there dwelling.”

The Mayflower had a crew of 30 while of the 102 passengers aboard only around half were Puritans with 28 male members of the congregation (many aged and past their prime) 20 women (3 of whom were pregnant) and a number of children. The rest were representatives of the company referred to by the Puritans as ‘Strangers’ and treated with suspicion.

It was the worst possible time of the year to be embarking upon such a voyage, progress was slow and with the sea rough sickness was rarely absent. In the meantime, huddled below decks in cramped and unsanitary conditions surrounded by damp discarded clothes, chamber pots and no little vomit where privacy was at a premium the Puritans made the best of a bad situation. Yet for all its unpleasantness it was for the most part an uneventful voyage; at one point a mast snapped and had to be replaced, a child was born they named Oceanus, and four people died of disease but there had been no life-or-death struggle against a raging sea, no attack by pirates, no seething resentment below decks that threatened mutiny.

On 9 November, after 65 days of sea land was at last sighted, but it was not the land they were looking for. Captain Jones soon ascertained they were off the coast of Cape Cod still some hundreds of miles from the Hudson Bay area and their intended destination. He was eager to move on but first some kind of agreement had to found between the Puritans and the Strangers as to what form any future settlement might take. Tensions had been mounting between the two groups for some time with both equally determined to assert their rights and freedom to do as they pleased.

The Puritans and Strangers had little in common other than self-preservation, which of course was no small thing, but if that were to be secured then some accord would have to be reached.

On 11 November an agreement was signed by 41 male passengers and on behalf of the 29 women aboard that declared in the name of the King they would work collectively for the common good and in the best interests of the colony they would establish. The Mayflower Compact, as it became known, would be a document of governance, a founding document – ten days later they elected the wealthiest among them, John Carver, to be their first Governor.

After a week spent undergoing repairs and a few brief forays ashore, after one of which William Bradshaw returned to discover his wife had fallen overboard and drowned, the Mayflower sailed north but hidden shoals, dangerous tides, adverse weather and inadequate charts soon saw Captain Jones turn south once more.

As they sailed along the coast landing parties under the command of Myles Standish, an experienced soldier who had been appointed military commander were sent ashore to survey the land for possible settlement. Certain criteria had first to be met: the land had to be arable, the location easily defendable and it must have a harbour for ships to dock. Finding such a place was easier said than done however, but there was evidence of previous settlement including rudimentary dwellings and burial grounds while abandoned foodstuffs were retrieved and taken back to the ship with a promissory note of future payment being left in its place.

Having heard many lurid tales of a violent and savage Indian not subject to God’s Beneficence the landing parties were well armed, and a first encounter with the Indians where arrows rained down and shots were fired in exchange only confirmed them in their worst fears - as a result they did not remain in any one place for too long.

On 17 December the Mayflower docked in Plymouth Harbour by which time weakened by hunger sickness had spread throughout and Captain Jones was desperate to land his cargo before it got any worse. Explorations continued then, but with even greater urgency.

On 21 December they stumbled across an Indian village that had been abandoned four years earlier when most of its inhabitants had been wiped out by plague. It was a Godsend, once called Petuxet, they would name it Plymouth, and here they would remain.

They immediately began constructing what buildings they could, but the shelter provided was barely adequate for the inclement weather and already weakened by disease more than half were to die during that first terrible winter. William Bradford was to write of their despair:

“It was a time of great cold and deprivation the foulness of which affected us all. It had pleased God to visit us then with death daily with so general a disease the living were scarce able to bury the dead and the well no measure sufficient to tend the sick.”

With starvation imminent a hill overlooking the settlement became the last resting place for many. Indeed, it appeared that Burial Hill as it became known would be the only permanent memorial to their presence.

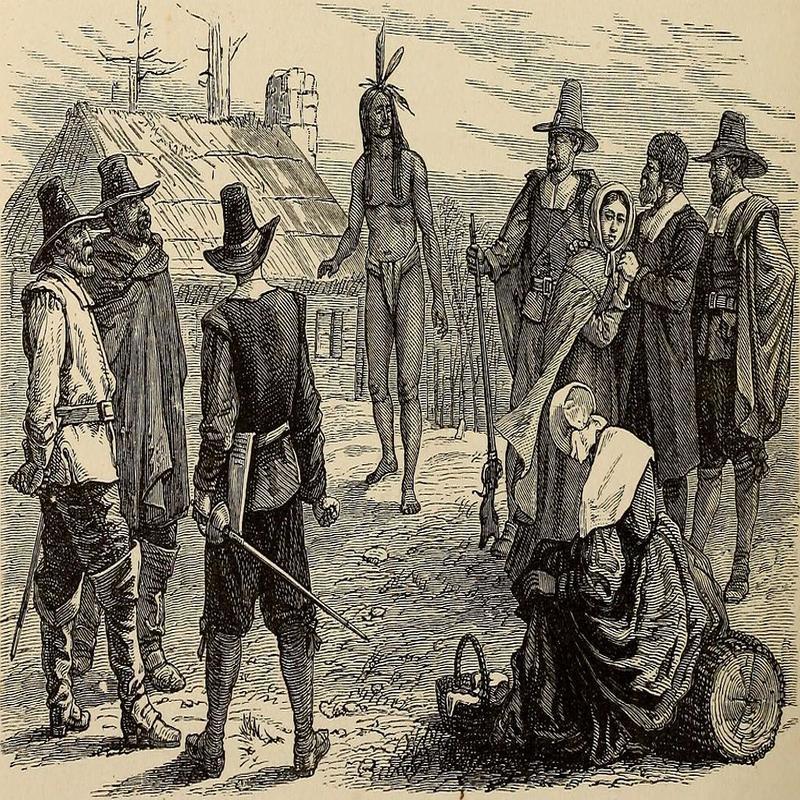

This would change in ways unimagined when on 16 March a tall, well-set scantily clad Indian strolled boldly into their camp greeted them in his broken English and demanded that beer and bread be brought. His name was Samoset he told them, and he was there on behalf of the Pakonet tribal leader Massasoit.

Encounters between the Indian and the white man were not uncommon, the English and the French had been trapping and fishing in the Cape Cod area for many years and Samoset had learned their language trading with them. But that isn’t to suggest relations were good and violent clashes were also common with massacres committed by both sides. But fighting with the white man was as nothing compared to the warfare waged between the tribes and when they weren’t stealing each other’s land and women and killing each other, then they were seeking to do so. Having been decimated by disease the Pakonoket were particularly vulnerable. Massasoit was no friend of the English but with their weapons, tools and know-how he recognised the value of being so. Under threat from both the Narragansett and in particular the warlike Abenaki, he sought them as an ally. So, Samoset departed the camp telling the settlers that he would return soon with his tribal leader and that they would talk together.

Samoset was to prove as good as his word for Massasoit had already decided how best to deal with these trespassers upon his land. Some had wanted him to attack them forthwith, to wipe them out but he had instead chosen the path of peace.

When Samoset did return four days later accompanied by Massasoit it was with a large retinue of warriors among whom was a man of Petuxet named Tisquantum, or Squanto as he would soon be known.

He had been abducted by an English raiding party some tears earlier, taken to Europe and sold into slavery. It would appear his captivity was less restricted than one might imagine for he was able to travel from a monastery in Spain to London from where he later took ship back to North America. In the meantime, he had not only become fluent in English but believed he understood them as no other Indian could and with the settlers for the most part being artisans and tradesmen with little farming experience it was, he more than any other who would save the Plymouth Colony from extinction. He showed then what seeds to sow and how to cultivate them, where to hunt and fish, and how to build homes more weather resistant. He also helped make and maintain the peace but his role as chief interlocutor between the English and the Indians also fuelled his own ambitions and it was not without justification that Massasoit believed he was conspiring with his English friends to replace him. Indeed, he was to imperil that peace when the English refused Massasoit’s demand that they hand him over for summary justice.

Before the crisis could escalate any further however, Massasoit fell ill and appeared near death. All tribal remedies had failed, and it fell to Edward Winslow with a mixture of common sense, concoctions from home and no little prayer to nurse him back to health. For this the Pakonoket Chieftain would be eternally grateful declaring “the English are my friends, they love me, and I shall never forget the kindness they have showed me.”

As long as Massasoit lived the peace would be maintained.

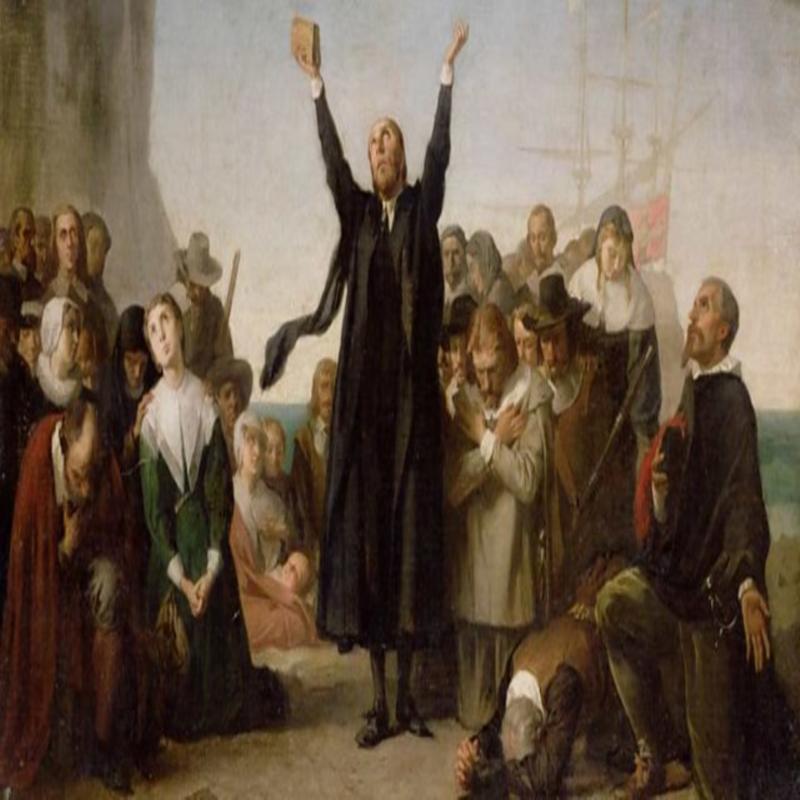

In the autumn of 1621, the settlers gathered in celebration of their first harvest. Joined by Massasoit and other Indians who brought along five deer for the table food was ample and the atmosphere one of amity and optimism. Plymouth colony, the first established on the North American Continent for a higher purpose than that of mere commerce alone, had survived against all the odds. It had been a miracle of sorts, and though the Puritans might disavow such interventions they remained firm believers in God’s Providence as also in time would others as that first Thanksgiving Feast took on a significance unimagined by those who had been in attendance. It would become a founding myth even if the details of its conception have become blurred in the mists of time; but then the reality of any myth lies not in its truth but its meaning, and more importantly its legacy.

The Pilgrim Father’s as they had been known since 1820 when the preacher Daniel Webster first coined the term were that myth and the community created by his handful of persecuted religious malcontents from the heart of rural England while never perhaps the ‘shining house on the hill’ as later described was nevertheless to prove one built on solid foundations.

The founding of America was not the founding of the United States of course (that would come later) but it was a seminal moment nonetheless; and it was to be in celebration of that first harvest that President Abraham Lincoln in the heat of civil war to preserve the Union would declare the fourth Thursday in November a day of national unity – Thanksgiving Day.

Tagged as: Tudor & Stuart

Share this post: