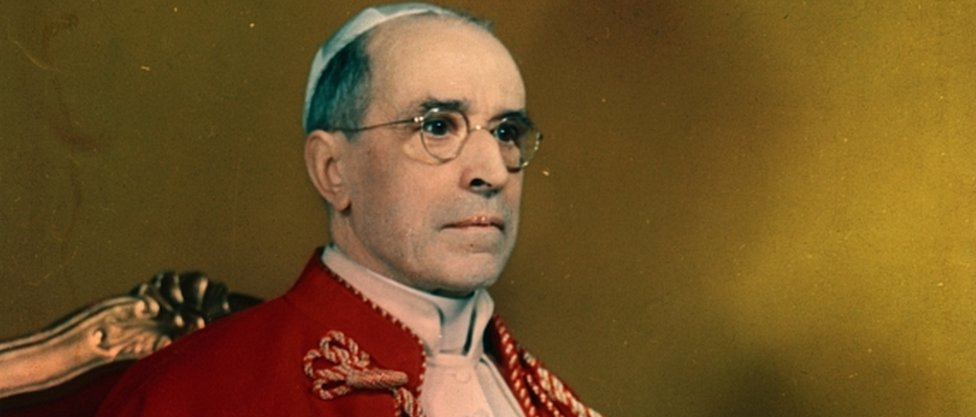

Pope Pius XII

Posted on 22nd October 2021

“Thy right hand, O Lord, is become glorious in power – thy right hand dashed in pieces the enemy. And in the greatness of thine excellency thou have overthrown them that rose up against thee, thou sendest forth thy wrath, which consumed them as stubble.”

(Exodus 15:6)

Few incumbents on the Throne of St Peter have been as controversial as Pope Pius XII who presided over the Catholic Church during one of the most troubling and perilous times in its history. It was to emerge from this period intact and as powerful as ever but at what cost, some might ask to its moral authority?

Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli was born on 2 March 1876, in Rome to an aristocratic family with strong ties to the Vatican. It was originally intended that he should be a lawyer and he did indeed gain a doctorate in law, but his presence was never to be felt in the Courtroom. Instead, he chose a career in the priesthood – it was his vocation, he said.

This was not a decision that disappointed his family whose Vatican connections along with his legal training they believed would help facilitate a rapid rise through the Catholic hierarchy, and they were right.

After completing his studies, the 23-year-old Father Pacelli, who was ordained a priest on Easter Sunday 2 April 1899, spent little time tending to the spiritual needs of his flock for he was a Vatican high-flyer and in 1901 was appointed to the Department of Extraordinary Ecclesiastical Affairs where he helped to codify Canon Law.

But his time spent crossing the T’s and dotting the I’s of Catholic dogma and other administrative minutiae was short-lived as he soon became a very effective Papal trouble-shooter travelling the world as the representative of the Pope abroad.

Over the next thirty years he was made Archbishop, Cardinal, Papal Nuncio, and Vatican Secretary of State; and Eugenio Pacelli’s spiritual life as a Man of God was destined to be spent in the very real world of secular politics.

In February 1929, after many months of difficult negotiations undertaken in large part by Francesco Pacelli, Eugenio’s elder brother, and Cardinal Pietro Gasparri the Vatican signed the Lateran Treaty which formally made Catholicism the established religion of Italy in return for the Church endorsing the Fascist Regime of Benito Mussolini providing it with the moral legitimacy it had previously lacked.

Although Eugenio had not been a leading figure in the negotiating team he had played a significant role nonetheless and had impressed enough to be appointed Vatican Secretary of State upon Cardinal Gasparri’s retirement the following year.

It was 1930, and Cardinal Pacelli in his new role as Secretary of State was to determine Vatican foreign policy in the decade that would witness the political reconfiguration of the European Continent, and this meant negotiating and striking deals with fascists.

On 20 July 1933, he negotiated a Concordat with Nazi Germany that protected Catholic Associations and their publications whilst also securing the future of Catholic education in the country. For this he oversaw the dissolution of the Catholic Centre Party which formed the focal point of traditional conservative opposition to the Nazi Government.

It was to prove a treaty unworthy of the paper it was written on and in time would greatly impede the ability of the Catholic Church to influence events in Germany.

He also signed a similar Concordat with the clerico-fascist regime of Engelbert Dollfus in Austria and was to lend his support to General Francisco Franco’s ‘Crusade’ against the Republican Government in Spain. Few people could be said to have had a deeper knowledge or better understanding of fascism than Eugenio Pacelli.

On 10 February 1939, Pope Pius XI died, and Cardinal Pacelli was the obvious successor. Indeed, the dying Pope had expressed his desire that he should succeed him but not all agreed: he was not spiritual enough, some said. Others thought him a theological lightweight and there were many who believed that he had sullied his reputation by seeming to do the Vatican’s dirty work but with war looming and thought of as more worldly than his rivals the Cardinals who had gathered in Rome to elect the new Pope opted for the pragmatic over the faith driven.

He may have had little experience as a working priest and lacked the spiritual grounding of his rivals, but it was believed that his understanding of global politics and his diplomatic cachet would be of benefit at what was obviously going to be a difficult time for the Church.

On 2 March 1939, Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli was elected Pope Pius XII.

Having witnessed Nazi Germany at first hand the new Pope was aware of their anti-Jewish views and of those policies already implemented against them following the Nuremburg Laws and had communicated his concerns to the Vatican. As a result, on 14 March 1937, his predecessor Pope Pius XI ordered that the Papal Encyclical Mit Brennender Sorge, or With Burning Concern, be read out that Easter during Mass at every Catholic Church in Germany. It openly condemned a Nazi ideology that placed man above God and exalted one race over all others stating that any notion of racial superiority was incompatible with Christian teaching.

This Encyclical has with some justification been praised as the only time a major institution (and not just a religious one) stood up to and roundly condemned Nazi racial policies, and as one of the architects of Mit Brennender Sorge this has often been used in Pius XII’s defence.

Yet nowhere in its pages does it openly condemn anti-Semitism while its primary concern is not with issues of race at all but with Nazi paganism which elevated the State above God as the supreme power on earth.

In the summer of 1941, Isaac Herzog, the Chief Rabbi of Palestine begged the Pope to intervene on behalf of the Jews being murdered by the Nazi Einsatzgruppen in Eastern Europe. In response, Pius telephoned his old friend the German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop to voice his concerns, but no formal protest was lodged.

When Philippe Petain, President of the recently formed collaborationist Vichy regime in France asked the Vatican if they had any objections to its proposed anti-Jewish legislation, Pius was quick to make it clear that the Church condemned anti-Semitism but then added the rider that the legislation did not conflict with Catholic teaching.

In April 1941, Pius granted a private audience to Ante Pavelic, President of the Nazi Puppet Government in Croatia, a regime so murderous that even the Nazi’s felt compelled to intervene to curtail some of its worst excesses.

Pavelic’s aim was to convert a third, expel a third, and murder a third of all Jews, Gypsies, and Serbs in Croatia, and as many as 700,000 were killed as a result. Pius never condemned the forced conversions that were carried out in the name of the Church over which he presided let alone the murders.

When in 1945, fleeing the Soviet advance Pavelic holed up in Rome he was given shelter by the clergy, provided with a passport by the Vatican, and smuggled out of Italy to South America, just like many other Nazi’s who escaped justice via the Roman Catholic ratline.

Similarly, the clerico-fascist regime of Josef Tiso who was himself a priest in Slovakia was actively endorsed by the Vatican. In 1942, under pressure from the Nazi’s it began to deport its Jews but as a Catholic State with direct ties to the Vatican Pius felt not just able but obliged to intervene and by October 1942, the deportations had ceased but by this time 58,000 or 75% of the total number of Jews in the country had already been murdered.

In April 1947, Josef Tiso, a spineless and haunted man was hanged for war crimes still wearing his clerical robes.

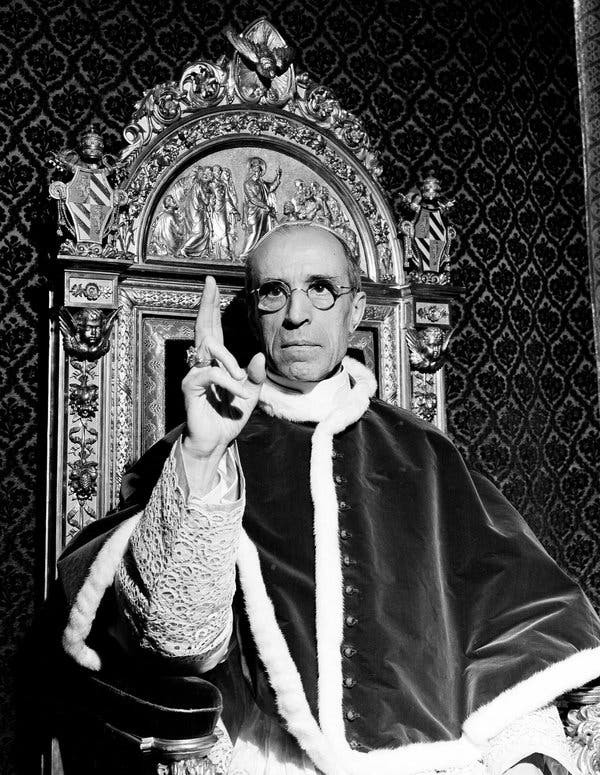

IIn October 1941, Pope Pius was asked by the American Representative to the Vatican to openly and formally condemn the atrocities against the Jews. His reply was that the Church wished to remain neutral in the conflict. In January 1943, Wladyslaw Raczkiewicz, the President of the Polish Government in exile asked the Pope to condemn the atrocities in Poland, again he refused.

In early 1943, the Italians who had always been lukewarm anti-Semites came under pressure from the Nazi’s to round up their Jews in preparation for deportation to the Concentration Camps. Mussolini, who had always prided himself on not being an anti-Semite and had often said that it was this that distinguished his brand of fascism from the crude and brutal kind of the Nazi’s, had since fallen. There was now no one in a position to stand up to Nazi demands, moreover there was no one upon whom Pius could bring pressure to bear should he have chosen to do so.

The round-up in Rome that began on 16 October 1943, was carried out at night to maintain secrecy but everyone knew what was happening and it was reported to the Pope almost immediately. Indeed, a close friend of his, Princess Enza Pignatelli Aragona rushed to the Vatican in person and with tears rolling down her cheeks told him: “Only you can do something.” He replied: “I will do all I can.” Yet despite expressing his horror to those in his presence and appearing genuinely distressed he wrung his hands and did nothing.

To his many supporters and apologists Pope Pius did all that he could in difficult and trying circumstances and there is no doubt that he did much on a personal level to help those fleeing from tyranny. That he provided financial assistance, established safe-houses, organised escape routes, gathered valuable intelligence, and permitted Jews and others to shelter within the confines of the Vatican City is well established.

In his Summi Pontificatus of October 1939, he had declared: “This is an hour of darkness in which the spirit of violence and discord brings indescribable suffering on mankind.” But still he condemned no one and he continued to condemn no one for the duration of the war despite being aware of the atrocities that were being committed. Even so, as an individual he did what he could but is it as a man or as the Pope of the One True Church that he should be judged.

Following the conclusion of the war Pius appointed many high-profile resistors of Nazi oppression to positions of prominence within the Church and actively sought reconciliation between those who had so recently been enemies but still his failure to condemn atrocities where they occurred hung like a dark cloud over the Vatican.

Always a tireless worker and with the events of the war weighing heavy upon his conscience Pius’s health quickly deteriorated and he was seriously ill for extended periods of his Pontificate but despite being advised to do so he refused to abdicate and on 9 October 1958, aged 82, he died of heart failure. His legacy remains however, and Pope Pius XII’s admirers and detractors exist in almost equal number:

Some would argue that he was a good man who did his best in impossible circumstances saving many lives and preserving the integrity of the Church at a time when very existence was in peril; others might ask what is the use of a Church that turns a blind eye to genocide?

It is easy to be critical of Pius XII the moral case against him being so easy to make but it should be borne in mind that as Pope he was responsible for the protection and safety of the many thousands of priests, nuns and others who worked for the church. He also had to secure church property and maintain the integrity of the faith at a time of war and the most unspeakable brutality. Neither was he a naive man and he knew the Nazi’s who had shown restraint in their dealings with the church up to a point would not hesitate to act should they feel threatened and had plans already in place to occupy the Vatican and to spirit the Pope away to a place of confinement.

Regardless, his detractors would say that as Head of the Universal Church and God’s Representative on Earth he had a moral obligation to speak out and condemn the atrocities that were being committed in particular the genocide against the Jews that both he and the Allied Powers had long ago been made aware of; that he should at the very least have issued instructions to the millions of Catholics and elsewhere across Occupied Europe to look to their conscience even if he shrunk from interdiction.

The British Government thought the latter describing Pius XII in 1941 as the greatest moral coward of our times?

The Vatican believes otherwise and just prior to his death Pope John Paul II declared that Pius XII had possessed the three heroic virtues of faith, hope, and charity. The process toward acquiring Sainthood had begun.

Tagged as: Modern

Share this post: