Propaganda in the English Civil War

Posted on 30th April 2021

Propaganda is considered an essential requirement in any war effort especially on the Home Front. It is needed to make the case for a war, to emphasise the dire consequences of defeat and to maintain morale at times of crisis. It is also necessary to create enmity towards what is often an unknown and previously unsought enemy. But Civil Wars are different in that we know our enemy. They are our neighbours, previously friends, even our kith and kin. They are wars where hatreds are magnified, disputes irreconcilable and bonds of affection shredded on differences of opinion.

The political crises of the 1640’s and the proliferation of the printing press had combined to make the English Civil War the first propaganda war in history. Between 1640 and 1660 more than 30,000 publications were printed in London alone. Many of these were written in plain English for the first time and were sold on the streets for as little as a penny making them available to the common people. It was to be political and religious propaganda on a grand scale.

The first great surge in propaganda saw a multiplicity of publications reporting in graphic detail the atrocities committed on Protestants by Irish Catholics during the rebellion of 1641. As the war abroad quickly developed into a political crisis at home the hunger for news saw the great debates of Parliament printed word for word and widely distributed

The hot air of Parliamentary dispute would soon spiral into a military conflict that few had foreseen but which the propaganda had foreshadowed and would continue with both sides having their own fully funded news sheets and for which two men more than any other were responsible.

Marchamont Nedham was born in Burford in 1620 and attended All Souls College, Oxford where he studied as a physician though he had ambitions to be a writer and when war broke out between the King and his Parliament he enthusiastically embraced the latter’s cause; not to the extent that he was ever willing to fight for it but he was willing to write for it and in August 1643 along with his fellow journalist Thomas Audley he published the Mercurius Britannicus, a news-sheet that ridiculed the King and his Cavalier supporters. Charles was according to Nedham, “a wilful King, which hath gone astray these four years from his Parliament, with a guilty conscience, bloody hands, a heart full of broken vows and protestations.” He would ask, “Where is King Charles? What’s become of him? Some say he has run away to his dearly beloved Ireland; yes, some say he ran away from his own Kingdom but very Majestically.” The tone was sneering and disrespectful.

Following the King’s defeat at the Battle of Naseby on 14 June 1645 he did untold damage to his cause by publishing the letters that had been retrieved from the captured Royalist baggage train that revealed not only that he was in secret negotiations with the Irish Confederation for support but also the private correspondence he had with wife Henrietta Maria; written in the most affectionate terms they appeared to show the King as a weak man bewitched by and subordinate to his Catholic Queen.

Although Parliament appreciated the propaganda value of the published letters such a devious and disrespectful act was something few were willing to own up and it left a bitter taste.

Nedham unconcerned by ethical or moral considerations continued to viciously attack the King’s person making fun of his speech impediment and his Scot’s accent so stumbling and incomprehensible, but when in May 1646 he accused the King of being a tyrant and a traitor he over-stepped the mark.

Even for a Parliament engaged in a war against its King such levels of disrespect were unacceptable; and so Nedham was arrested and the Mercurius Britannicus closed. He was released from prison soon after having paid a £200 surety on his future good behaviour.

Following the end of the Civil War, Nedham who had been keeping a low-profile since his release from prison obtained an audience with the King who was being detained at Hampton Court. In his presence he apologised for his previous writings and begged the King’s forgiveness which was duly received.

Perhaps out of feelings of bitterness for his previous treatment at the hands of the Parliament he had supported he now agreed to write for the Royalist cause and between September 1647 and May 1649 he published the Mercurius Pragmaticus which became popular for its vitriolic and satirical attacks upon the leading Members of Parliament and the Army.

So influential did the Mercurius Pragmaticus become that Nedham was forced underground and had to publish it in secret but in June 1649, his luck ran out and he was again imprisoned.

Fortunately for Nedham he had made many powerful contacts during his time writing for Parliament and in November they combined to secure his release from Newgate Gaol. They had only done so only on condition that he again direct his journalistic skills in Parliaments support. So he changed sides once more and provided with a £50 grant he published the Mercurius Politicus and working alongside John Milton became the leading propagandist for the new Commonwealth.

The Mercurius Politicus became the weekly mouthpiece for the new regime, and he was to introduce a number of features that have since become common to newspapers around the world, in particular the introduction of the Leader Column where the newspaper ceases to merely report events but expresses its own view on the issues engaging its readers.

Following the Restoration in May 1660 fearing for his life Nedham fled abroad but he was nothing if not a political survivor and he returned to England after securing a pardon which it is widely believed he bought at great expense.

Marchamont Nedham was perhaps England’s first great journalist, but he was also wise enough to know when to cease his activities. Upon his return to England, he sought the quiet life working for the remainder of his life as a doctor only emerging once more as a writer in 1676 when he was commissioned by the Government to pen a satirical attack upon the leader of the Whig Opposition the Earl of Shaftesbury. He died peacefully in his bed two years later.

Sir John Birkenhead was born in Northwich and like his rival Nedham he also attended All Soul’s College in Oxford though they were not contemporaries. Unlike Nedham however who saw the Civil War as an opportunity to hone his skills as a journalist Birkenhead always had a political career in mind.

The publication of a Royalist newssheet had been strongly suggested to the King by George Digby Earl of Bristol, as the only means by which the Royalist cause could be promoted in Parliament controlled London. The King agreed and in January 1643, Birkenhead who was always hanging around the Royal Court seeking a position was appointed editor of the soon to be published Mercurius Aulicus.

Unlike Nedham who was a journalist and contributed a great deal to his publications Birkenhead was at best an occasional author and much of the responsibility for the writing fell to Peter Heylin and various other people such as John Cleveland, but it was Birkenhead who was responsible for the tone it adopted and unlike those on the Parliamentary side he had no scruples regarding its content.

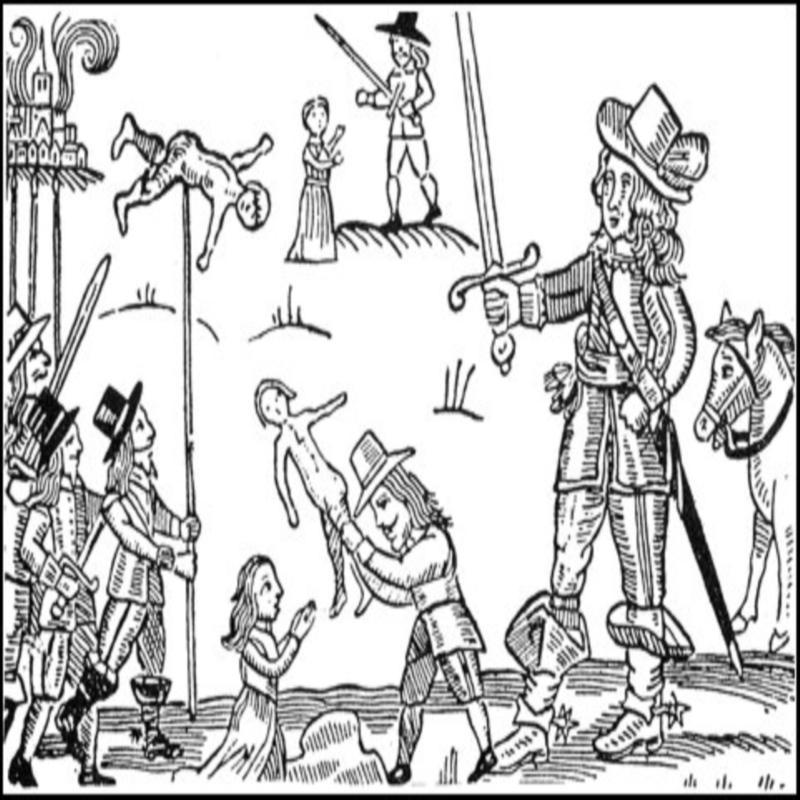

The Mercurius Aulicus was a scurrilous rag unfettered by moral considerations that printed scandal and gossip and played mercilessly upon the fears and obsessions of the King’s Puritan opponents.

Birkenhead ensured that the Mercurius Aulicus was published on a Sunday so as to offend the Puritans and then smuggled into London where it was sold on the streets and in taverns by women who had always been generally more sympathetic to the King’s cause and were also less likely to be stopped and searched.

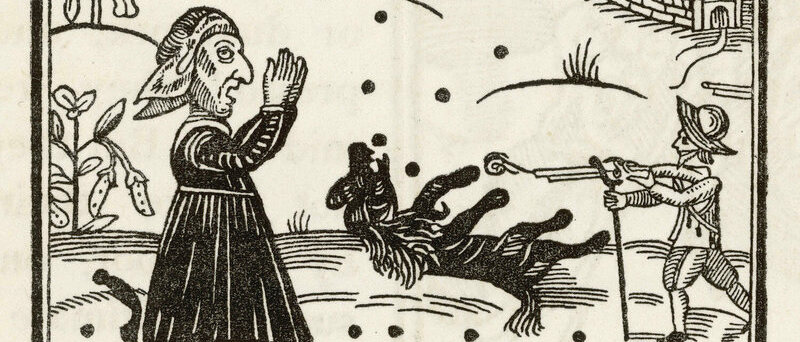

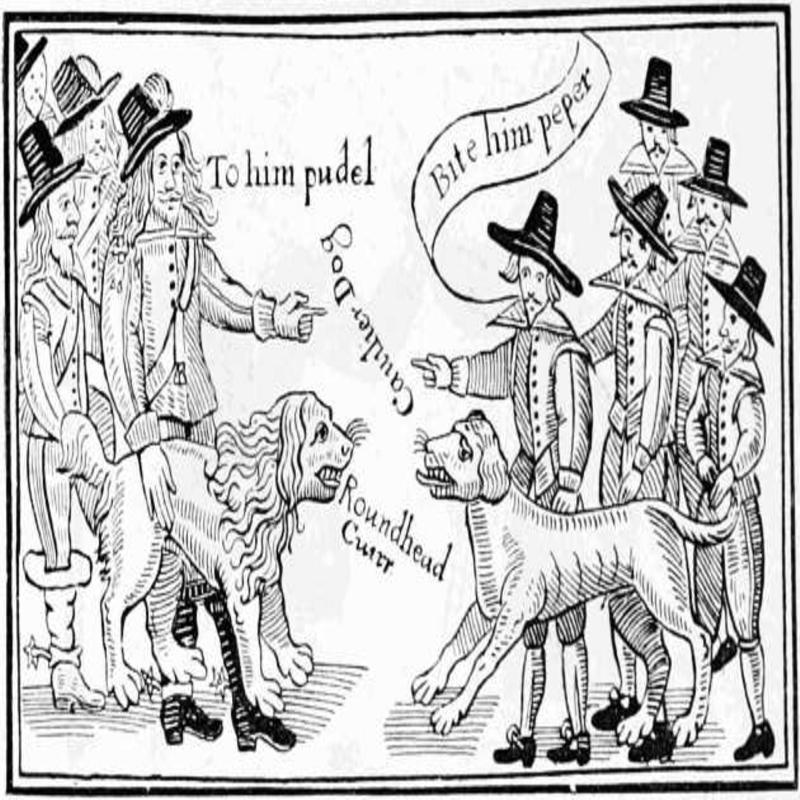

The biting satire of the Mercurius Aulicus and its often very funny attacks upon the Puritans made it a popular publication even among those of less extreme religious views who did not necessarily support the King. A particular target was the Puritan obsession with the hated Prince Rupert’s toy poodle Boy, who they believed was the devil’s familiar, spoke to the prince in a language only known to them, could turn itself into a mermaid and was sent on secret spying missions. The Royalists in response commissioned it a Colonel in the Cavalier Army.

It was to remain a popular publication throughout the war despite the penalties being harsh for those found in its possession and the reputation of those selling it for doing so at a greatly inflated price and thereby making a few pennies for themselves.

Birkenhead who unlike Nedham was a man of conviction was to remain constant in his loyalties and as such was imprisoned several times during the Commonwealth for expressing his Royalist sympathies a little too strongly.

He was rewarded for his loyalty following the Restoration being knighted in 1662. He was to go on to become a founder member of the Royal Society and fulfil his ambition for a political career becoming the Member of Parliament for Wilton in Wiltshire.

He died on 4 December 1679, a little over a year after his great rival in the war of words not guns, Marchamont Nedham.

Tagged as: Tudor & Stuart

Share this post: