Putney Debates

Posted on 24th January 2021

By the summer of 1647 except for the Royalist Army fighting alongside the Catholic Confederation in Ireland the English Civil War was to all intents and purposes over. Yet despite their victory to a great many in the parliamentary army little seemed to have changed. That man of blood Charles Stuart may have been under lock and key, but he was still King and negotiations were underway to find a settlement whereby he could remain so.

The Parliament that had been called in 1641 remained extant, the House of Lords still sat and the social hierarchy remained unchallenged. But then to those in power there seemed no reason why it should be challenged. The idea that England should be anything, but a Monarchy and an ordered society of Lords, Gentlemen and Commoners had barely occurred to anyone - but what had been a conflict of arms would soon become a conflict of ideas.

In February 1647, Parliament decided without consulting the army that those regiments which had not volunteered for service in Ireland would be disbanded before any resolution on the issue of their outstanding pay. The soldiers refused to disperse and instead the following month they petitioned Parliament demanding the immediate redress of their grievances including indemnity for actions carried out under orders and that provision be made for the widows and orphans of those killed in action.

Parliament sought to have the petition suppressed but without the support of the Army High Command they were unable to do so. Nonetheless, they refused to debate it and soon bands of unpaid, unemployed, and disgruntled soldiers became a familiar sight on the streets and country lanes of England. Indeed, their behaviour had become so threatening that the leading M.P Denzil Holles accused them of being both enemies of Parliament and the State.

After five years of brutal struggle and great sacrifice where they had shed their blood in Parliaments cause such insults were hard to bear particularly when London’s Militia Bands were mobilised to counteract the army should there be an attack on London or the Houses of Parliament itself. Indeed, so likely did the prospect of conflict appear that to take the heat out of the situation the Army Commander Sir Thomas Fairfax ordered it to gather at Newmarket.

In the meantime, King Charles had been prevaricating in his negotiations with Parliament in the hope that his opponents in parliament so united in pursuing war would fall out with each other trying to secure the peace, and this indeed appeared to be happening. He was then, in no rush coming to terms.

On 5 June, Cornet George Joyce with 500 men seized the King from Holdenby House and delivered him to Sir Thomas Fairfax’s headquarters thereby removing him from Parliament’s control. Fairfax was less than pleased and considered charging Joyce with disobedience, but it seems likely that he had been acting on the orders of other members of the Army Council, most probably Oliver Cromwell and Henry Ireton. They were aware of the radical views that were being expressed by many within the rank-and-file of the army and were afraid that the greater the delay in coming to a settlement with the King the greater the likelihood that the political uncertainty would result in conflict and threaten the social order, they wished to preserve. Now they had the King in their custody they could circumvent a quarrelsome Parliament and negotiate with him directly.

The settlement they tried to impose upon Charles known as the Heads of Proposal, presented with all due deference to His Majesty, was surprisingly lenient in its terms, and they expected a positive response. It had five main demands: those Royalists who had supported the King were to be prevented from holding public office but only for five years; the Book of Common Prayer was to be introduced after all but would not be mandatory; the Church hierarchy of Episcopacy and Bishops was to be retained; toleration of religious worship (except for Catholics) was to be guaranteed; and Parliament was to control the appointment of all State Officials and Army Officers for the duration of ten years.

The terms were generous in the extreme and it was perhaps only a King who believed he ruled through Divine Right who could have turned them down. It was to prove an error of judgement on the part of both for once it was debated in Parliament on 23 September and became widely known it caused outrage - was this really what so many people had fought and died for?

Oliver Cromwell had made it plain he only wanted men ‘who know what they are fighting for and love what they know’ to be in his New Model Army and he found them. His troops were abstemious and disciplined just as likely to be wielding a pocket Bible in one hand as they were a sword in the other. But they had also been influenced by Leveller ideas and were no longer just fighting against the King but for an ideal. Even if it was an ideal that their Commander-in-Chief did not necessarily share.

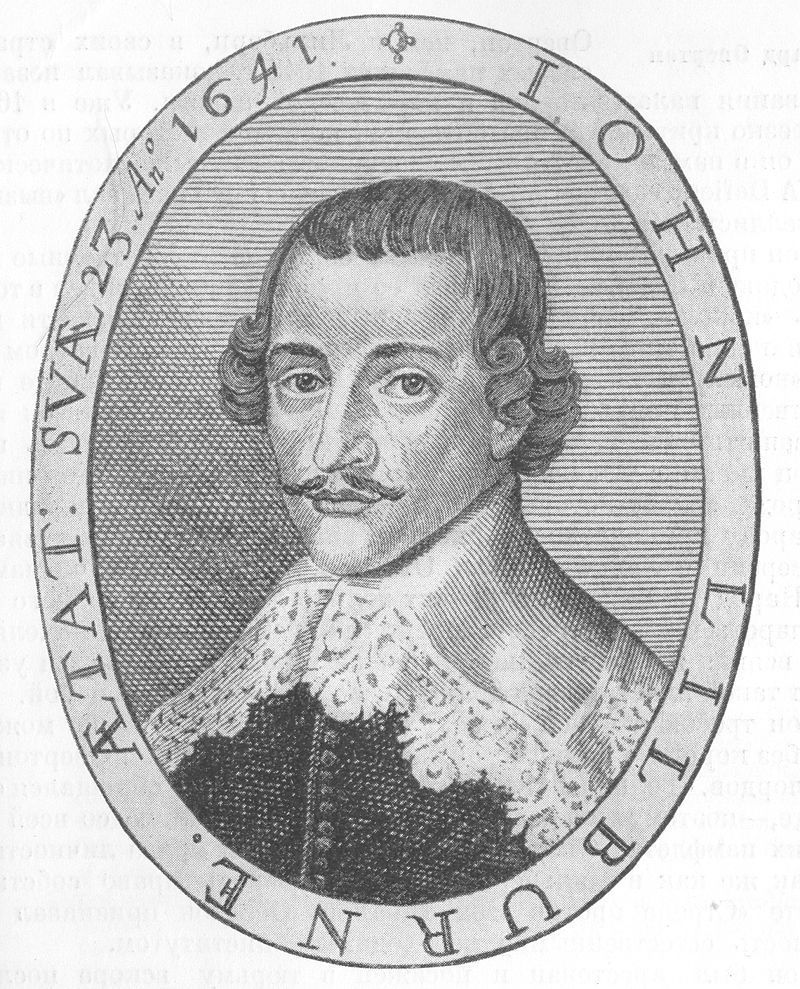

The most famous Leveller was John Lilburne who had been a radical and a political agitator all his life. By the time the Civil War broke out he had already been pilloried, flogged, starved, beaten, and imprisoned many times. He had even been hauled before the Court of Star Chamber and warned of the dire consequences of not ceasing his agitation. But he was not so easily intimidated and would not be cowed.

He believed in the Rights of the Freeborn Englishman, those rights that every Englishman had from birth and could not be taken away by Kings or Governments, rights that went back to Magna Carta and beyond to the time of Alfred the Great and King Arthur.

Following the raising of the King’s Standard at Nottingham he had volunteered to serve in the Parliamentary Army but despite impressing as a soldier and rising to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel he did not have a good war. He was captured early on and imprisoned at Oxford for six months where he was fortunate not to succumb to disease in the foul and insanitary conditions of the gaol. When his captors realised, they had the notorious John Lilburne they threatened to execute him but fearing tit-for-tat reprisals if they did so he was later exchanged for a Royalist Officer. But things hardly got any better, he lost all his worldly goods in the Royalist sack of Newark and besides almost at one point dying from wounds he wasn’t paid for the last two years of his military service.

In July 1645, he was imprisoned for criticising Members of Parliament he accused of living in comfort while others fought and died in their cause. He was soon released but less than a year later was again locked up in the Tower of London for denouncing his Commanding Officer the Earl of Manchester as a Royalist sympathiser - and so it went on for Lilburne.

Yet for all his insubordination he was a courageous and committed Officer and was admired by those who served under him. Indeed, his criticism of the Earl of Manchester was shared by Oliver Cromwell and for a time he and Lilburne became friends, but that wasn’t to last.

Now that the war was as good as won for Parliament, Lilburne could return to what he did best- political agitation.

Leveller was a term disliked by Lilburne as it inferred that they wanted to reduce all men to a base level of existence, but it later became such common usage that he adopted it as a means of recognition. Being so widely acknowledged as part of the political debate they now made specific demands: they would settle for nothing less than manhood suffrage without any property qualification; wealth would no longer define who was worthy of respect and there would be equality before the law. They also demanded religious toleration and the end of imprisonment for debt. Lilburne had not yet considered female enfranchisement despite the prominent role that Leveller women played in the movement.

Leveller propaganda and publications were prominent on the streets of London often spread by the many women involved who were not liable to be searched. Meanwhile, the leading Levellers such as Lilburne, Richard Overton, William Walwyn and John Wildman gave talks and lectures targeting army camps where their views quickly became influential among the troops with many of them wearing green ribbons in their hats or pinned to their uniforms as a sign of their allegiance to the Leveller cause.

The Heads of Proposal had angered the army radicals not just its terms but the way they had been agreed without consultation and without reference to their grievances - they were not willing to be ignored any longer.

Henry Ireton, who was Oliver Cromwell’s son-in-law and a lawyer by profession was an enthusiastic proponent of the Heads of Proposal and was greatly irritated by the army’s negative attitude towards it. Angered by the publication of the Representation of the Army which called for the election of a new Parliament on a wider franchise and for the army to be directly involved in the settlement of the nation it was he more than any other who pressed for a meeting to debate the issues. Cromwell was more ambivalent. The New Model Army was his creation, they were his people He did not like to be seen to oppose them.

The meeting between the Army Council and representatives of the rank-and-file was set for the autumn and procedures were hurriedly put in place to bring some order to it and to set an agenda. Eight cavalry regiments each elected two representatives known as the Agitators to convey their demands to the Army High Command referred to as the Grandees, Sir Thomas Fairfax, Oliver Cromwell, and Henry Ireton.

The Representation of the Army was originally intended to form the criteria upon which any discussion would take place, but it was soon overtaken by a new manifesto, The Case of the Army Truly Stated, which demanded more specific political reforms such as biennial elections, and a new written constitution. The tone of the debate had changed before it had even begun from criticism of the Heads of Proposal to the very future of the country and how and by whom it should be run.

The Putney Debates as they became took place at St Mary’s Church of the Virgin then on the outskirts of London between 28 October and 9 November 1647. Sir Thomas Fairfax, a soldier not a politician who would find any reason not to attend was mysteriously ill so Oliver Cromwell deputised as Chairman, but it was to be Henry Ireton who would be the Army Council’s most eloquent spokesmen.

The Agitators were represented in the main by Colonel Thomas Rainsborough, his brother William, Private Edward Sexby, and the civilian Leveller John Wildman. It hadn’t been considered prudent to invite John Lilburne who no doubt would have got himself arrested.

The meeting would begin every day in an atmosphere of solemn piety with prayers and a sermon before the two camps sitting on opposite sides of a large oak table proceeded to begin a debate that would quickly descend into an argument, and often a furious one.

The affair had begun badly on the first morning of the first day when Henry Ireton made it clear from the outset that he was not there to discuss either the abolition of Parliament or of the Monarchy and would countenance no such thing. The Agitators, most notably Edward Sexby, wanted to know why then they had fought this war at all if nothing was to change. To which Ireton replied that it was to prevent one man’s word being law.

The most famous exchange took place on the third day of the discussions between Thomas Rainsborough and Henry Ireton.

Rainsborough, a tall, rugged, and heavily built man with an intimidating presence had been arguing that the Freeborn Englishman had a natural right to full participation in all the affairs of State and other aspects of society. Ireton, delicate and refined by comparison, vehemently disagreed arguing that any such levelling down would endanger the safety and security of the Kingdom and that yielding to natural rights would undermine civil rights, or that which comes with the possession of property and the responsibility it entails.

Rainsborough: . . . for really I think the poorest he that is in England hath a life to live, as the greatest he; and therefore truly, I think it is clear, that every man that is to live under a Government ought first by his own consent put himself under that government; and I do think that the poorest man in England is not bound in a strict sense to that government that he hath not had a voice to put himself under.

Ireton: . . . no person hath a right to an interest or share in the disposing of the affairs of the Kingdom, and in determining or choosing those that shall determine what laws we shall be ruled by here, no person hath a right to this that hath not a permanent fixed interest in this Kingdom.

Rainsborough: I do not find anything in the law of God that a Lord should choose twenty burgesses, a Gentleman two, and a Poor Man none. I find but no such thing in the law of nature, or the law of nations. But I do find that all Englishmen should be subject to English law.

Ireton: I would have an eye to property, property is the most fundamental part of the constitution of this Kingdom, which if you take away all by right of nature, one man hath an equal right with another in choosing him that shall govern, then by the same right of nature he has the same equal right of nature to any goods he seized, to the land, to anything he may choose. Then where shall we end up?

The discussion had become so heated that Oliver Cromwell who had chosen to keep his counsel for much of the debate felt obliged to intervene:

"I know nothing but this, the most yielding have the greatest wisdom. No man says you have a mind to anarchy but that the consequences tend to anarchy must end in anarchy. We should not be so hot with each other."

Cromwell who was to prove a better soldier than he ever would be a politician had nonetheless learned a political trick or two. He suggested that the procedures be put in place to form a committee, that the matter could be deferred to a later date when both parties had calmed down, had given due consideration to all things, and had clearly heard the word of God. The Leveller’s were not to be so easily hoodwinked and remained adamant that matters could not be put aside and that the meeting remain in session until they were resolved, and it seemed for a time that the Army Council would have to yield to at least some of their demands.

But it was not to be through debate that the events at Putney would be concluded however but the news received on 11 November that the King had escaped his captivity at Hampton Court. Reunited once more by the threat of a Royalist resurgence both parties retired to their respective camps to prepare for the resumption of hostilities, one side frustrated no doubt the other, dare I say it, relieved.

It had been decided before they departed that the Agreement of the People would be re-drawn by a Committee of Officers and presented before a mass-meeting of the army for their approval. When it was four days later, on 15 November, near the town of Ware in Hertfordshire it had become just another version of the Heads of Proposal with conciliatory words and a promise to petition Parliament on the soldier’s behalf for the payment of the money owed them. It also demanded that they swear an oath of personal loyalty to the Army Commander Sir Thomas Fairfax and the Body of the Army Council.

The Agreement was accepted by the bulk of the army whose primary concern had always been the settlement of their arrears of pay but a few of the more radicalised regiments refused to be satisfied by a few vague promises, reminders of shared hardship and pleas for their loyalty at a difficult time. At first, they expressed their displeasure with jeers but soon began verbally abusing and jostling their Officers, when they were ordered to disperse they refused. Instead, around 400 of them marched out of camp making for Banbury near Oxford.

Learning of what became known as the Corkbush Field Mutiny Oliver Cromwell rushed from London with loyal regiments determined to crush the rebellion before it spread and infected the rest of the army. Travelling non-stop he reached Banbury late in the evening of 16 November and immediately confronted the rebels. He thanked them for their courage, implored them to remain loyal and to trust in their betters, and pray God not take up arms, but when he was mocked and heckled his temper snapped. He ordered the soldiers disarmed and riding up and down the line pulled the ribbons they were wearing from their hats and uniforms.

Four of the most vocal of them were then singled out for exemplary punishment and they were made to roll a dice to see which one of them was to be executed. The unfortunate man was Private Richard Arnold.

Oliver Cromwell’s decisive action had prevented elements of the army from attempting to seize power for themselves and though it was not to be the last mutiny it was the most serious. Not long after the army was sent to Ireland to vent their anger on the one enemy who could still be guaranteed to unify them.

The Leveller’s had lost the argument for radical reform not in the debating chamber but at sword point and over time Leveller influence within the army’s ranks dissipated but their ideas did not disappear rather they evolved.

In January 1649, Gerrard Winstanley a failed businessman and lay preacher along with several others published a pamphlet entitled The New Law of Righteousness in which he stressed the right of the common people to cultivate the land as they pleased:

In the beginning of time God made the earth. Not one word was spoken at the beginning that one branch of mankind should rule over another, but selfish imagination did set up one man to teach and rule over another.

They referred to themselves as the True Levellers but were more commonly known as The Diggers. They would neither petition Parliament nor the Army for rights or concessions but would seize the land for themselves.

In the early spring of 1649, Winstanley with around thirty followers occupied land on St George’s Hill in Surrey and began to plant seed and fell trees to build houses. The local landowners were furious at what they saw as the theft of their property and demanded from the Government that they act. Freed from the constraints of his loyalty to the army this time Oliver Cromwell was in no doubt that swift action must be taken to quell blasphemous notions that one man’s property is another man’s property and that any man could do as he pleased. He told Committee in Parliament that “You must crush them, or they will crush you.”

Sir Thomas Fairfax was despatched with the army to remove the Diggers from the land but he did not share Cromwell’s great fear of a social upheaval and upon speaking to Winstanley concluded that they were doing little harm and advised the landowners to pursue the matter through the Courts. Instead they hired thugs, many of them ex-soldiers, to rough up the Diggers, destroy their houses, and plough up their crops.

The Diggers were forced to abandon St Georges Hill, but they merely went elsewhere to Kent and Northamptonshire. Yet again they were pursued, harassed, and intimidated. Winstanley complained bitterly to Parliament about their treatment but to no avail. By the end of the year the Digger movement had been beaten into submission.

Gerrard Winstanley was to prove himself no John Lilburn. Having seen his experiment in social egalitarianism brutally crushed he simply retired quietly back into the world of commerce.

Leveller radicalism had effectively been eradicated from English political life by 1650 but this did little to deflect John Lilburne from his own chosen path of righteousness and he continued to agitate as he had always done for equality and the rights of the common man, and so in 1652 he was banished from England and forced to seek exile in the Netherlands.

He was to write many times to his old friend Oliver Cromwell who had long ago concluded that Lilburne was a dangerous madman, requesting permission to return. When this was refused, he returned anyway and was promptly arrested and imprisoned in Newgate Jail.

Over the next five years he was to be moved from prison to prison, released on licence, re-arrested and sent back to prison, and so on and so forth; but it was no longer the harsh confinement he had previously been used to. In truth, despite the fact that he was regarded as being too much of a risk to be set free there was a grudging respect for Lilburne even from those he counted among his enemies. His honesty and willingness to speak his mind regardless of the consequences was admired even if the words he chose and the views he expressed were often not

In 1656, he became a Quaker and was permitted to attend their meetings and make regular visits to his family. The freedom of movement he was granted came as a great relief to him even though he was kept under constant surveillance.

On 29 August 1657, John Lilburne the leader of the first ostensibly democratic political movement in England and an inveterate thorn in the side of the Establishment died suddenly while on a visit to his wife, aged 53.

The Putney Debates, for which Lilburne was the inspiration if not a participant, are now considered to be a pivotal moment in the evolution of progressive and democratic political thought in England, yet for 250 years they remained a virtual secret with the documentation relating to them not being rediscovered until the 1890’s.

Tagged as: Tudor & Stuart

Share this post: