Queen Victoria's Coronation: A Botched Affair

Posted on 22nd January 2021

At 6 o'clock on the morning of 20 June 1837, the young Princess Alexandrina Victoria of the House of Hanover and Saxe-Coburg Saalfeld was awoken to be informed that her uncle King William IV had passed away during the night and that she was to be Queen.

Although she had been heir to the throne for some time as the daughter of Prince Edward Duke of Kent, the fourth son of King George III, it should never have been so, and following her birth there had been little expectation that she would be anything more than a minor Princess of the Royal Blood - a blue-blood bargaining chip in the marriage bed of European dynastic entanglements.

At the time of her accession to the throne the Hanoverian Monarchy had never been more unpopular, the dissolute behaviour of her uncle’s which stood in stark contrast to the sober and hard working image of their father George III, seemed merely the extension of the often absurd figure of the Prince Regent and future George IV, and she had only become Queen because the fecundity of their many mistresses had not been replicated in the royal marriage bed.

As such, a Coronation was as likely to be the cause of a riot as it was a day of national celebration, and it was to be delayed for more than a year. Not that this was any guarantee that it would pass off peacefully.

But a young Queen, the first since Queen Anne 120 years earlier, was at least a break with the recent past and the fact that she was the niece and not the daughter of her immediate predecessor provided some distance from the behaviour of her disreputable and discredited uncles.

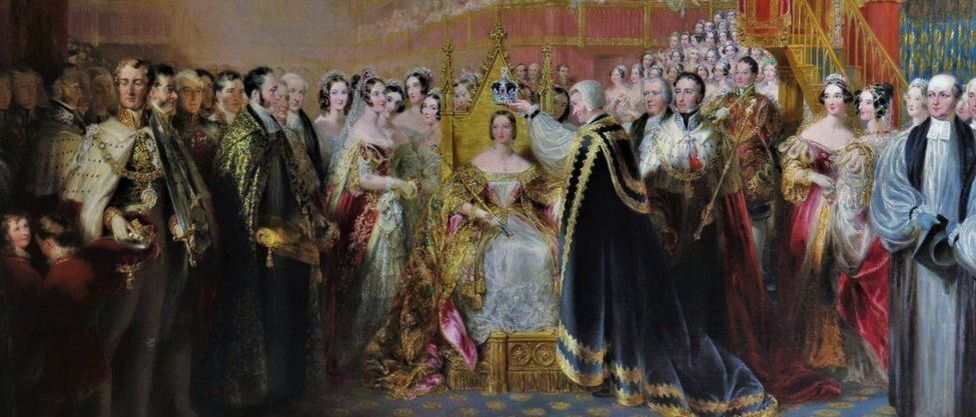

So there was little enthusiasm in the country for the Coronation but on 28 June 1838 the people of fashionable London, never ones to miss an opportunity to dress up and have a party, turned out in large numbers to watch the procession of the Queen’s gold carriage resplendent in the sunshine drawn by immaculately groomed and plumed horses with uniformed soldiers either side and accompanied by a military marching band, make its way through the gates of the recently built Buckingham Palace towards Hyde Park Corner and down Piccadilly through St James, Pall Mall, Charing Cross, Whitehall, and onto Westminster Abbey. The fresh-faced young Queen clearly excited by the occasion and who was seen often smiling and waving with enthusiasm made a favourable impression with the many onlookers who crammed the procession route. It seemed like a grand affair but the service inside the Abbey was to be little short of shambolic.

The Coronation ceremony which had long ago fallen into neglect was an essentially medieval pageant which seemed irrelevant to a modern age and some of its more arcane rituals such as the Queen’s Champion riding forth and challenging any dissenters to a duel had already been abandoned while many of the customs that remained appeared nonsensical and were little understood.

There had also been no formal rehearsal and a ceremony that was intended to last a little over two hours would in fact take almost five, a long time for an excitable young woman to remain solemn and dignified as in the confusion there was considerable inactivity and long periods of excruciating silence. That she did so was a credit to the self-discipline acquired from a childhood spent mostly in solitude and introspection. Even Benjamin Disraeli, not a man inclined to be critical of Monarchy felt compelled to express his dissatisfaction: “People were always in doubt as to what came next, and you could see the want of rehearsal.”

Inside the Abbey there was an 80 piece orchestra and a 150 strong choir but the music was to be the cause of some concern particularly as the conductor Sir George Smart, burdened with the responsibility of elevating proceedings from the earthly and the mundane to the heavens and the Greater Glory of God was hampered by his insistence that he play the organ himself whilst trying to direct the musicians at the same time. Long periods of orchestral inactivity ensued as the perplexed congregation stood around pondering what to do and whether to go.

Neither was the music chosen for the occasion free of criticism considered by some as eclectic at best and inappropriate at worst but then the man who had originally been appointed to design the audio tapestry of the great event had died the previous year.

No duty other than the commitment to serve God is of greater significance to the Church of England than the anointing of Monarchs but the Archbishop of Canterbury William Howley had forgotten his spectacles and his somewhat garbled reading from a pre-prepared text and the prayer book was only cleared up when it was pointed out to him that he was holding them upside down.

Similarly bungled was the placing of the ring on the Queen’s fourth finger, the ring which had earlier been measured for her little finger so therefore didn’t fit and had to be forced causing her no little pain, as Victoria was later to relate.

As the Coronation drew to its close the ceremony of homage took place as the great and the good of the nobility, the Dukes, the Earls, and others dressed in all their ermine and robes stood in line of seniority to pledge fealty to the new Monarch. Toward the back of the queue stood the 82-year-old Baron Rolle who weighed down by costume and no doubt addled by heat exhaustion and maybe a little too much claret stumbled as he ascended the steps to the throne and perhaps taking his name too literally fell backwards. When he attempted to ascend the steps a second time the same seemed about to happen again when the Queen breaking with protocol rose to her feet to help him. As she described in her journal:

Poor old Lord Rolls who is 82 and dreadfully infirm, fell in attempting to ascend the steps rolled right down but wasn’t in the least bit hurt, when he attempted again to ascend the steps, I advanced to the edge, in order to prevent another fall.

Many present viewed the young Queen’s rush to assist an elderly gentleman endearing but others less sanguine considered it a breach of precedent undignified in the extreme.

Following the ceremony, and the Queen’s third costume change of the day, the guests retreated to St Edward’s Chapel where the altar was somewhat irreligiously covered with plates of meat, sandwiches, half-filled decanters, and unopened bottles of claret.

Victoria at least had enjoyed her day and deemed it a great success as indeed did many others, but not all. .

The writer Harriet Martineau of whose books the young Victoria was particularly fond of and had been invited to attend the Coronation ceremony at her pleasure wrote a humorous but less than complimentary piece describing the events as barbaric, worthy of the Pharaohs, and an offence to God.

The Radical press, particularly in the north of England far away from the glitter of the occasion were highly critical of the money spent, almost £80,000, on an institution that was seen as increasingly anachronistic and irrelevant. But then little could the critics have imagined they had just witnessed the beginning of a reign lasting 63 years and 7 months would herald an era of unprecedented change, wealth, power, and influence never experienced before and never to be seen again.

Share this post: