Ravachol, Vaillant and Henry

Posted on 12th September 2021

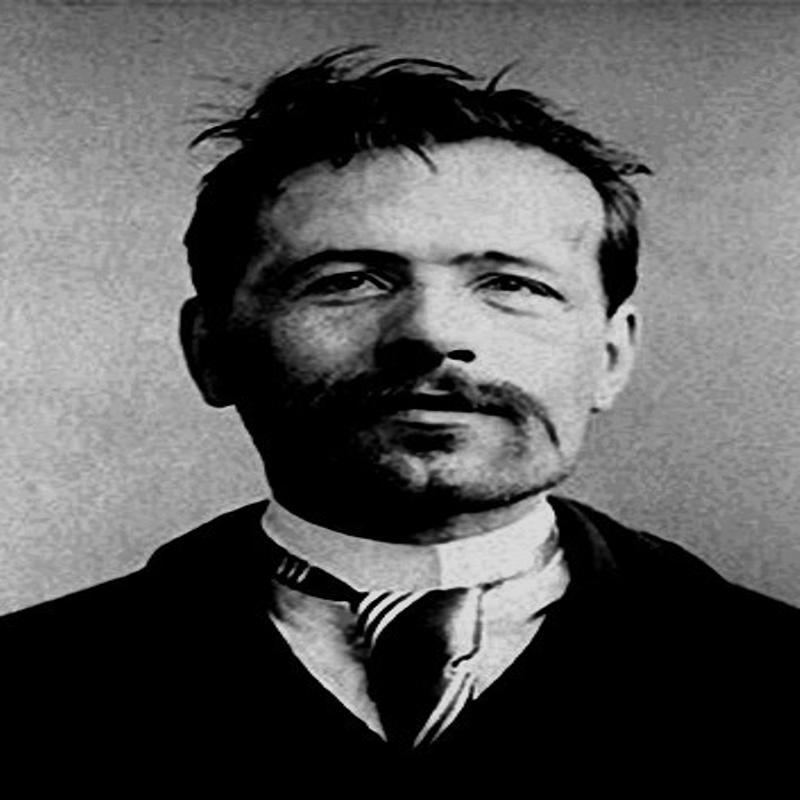

Francois Claudius Koeningstein, known to posterity as Ravachol which was his mother’s maiden name was born on 14 October 1859, in the small town of Saint-Chamond in Eastern France to a poor family who were soon to be made poorer by their father’s abandonment of them. It would fall to the young Francoise, then, still only a child, to support his mother and younger siblings. He quickly turned to crime to do so.

When he lost his job as an assistant dyer tormented by starvation and the harrowed faces of those, he could not provide for he found salvation not in God but the political credo of anarchism.

It told him that property was theft, that the justice system established to protect it immoral, and that the Government which made and enforced the laws was a tyranny. Only by its destruction could there ever be freedom and equality and only then could there be a better world.

On 1 May 1891, at Fourmies in Northern France the army fired upon workers at a May Day Rally killing 14 and wounding 40 some of them women and children. The rumour soon spread that the shooting had been a deliberate act intended to test the new but as yet untried Lebel machine gun.

On the same day as the Massacre at Fourmies the police attacked a small gathering of anarchists in the Parisian suburb of Clichy during which pistols shots were exchanged and nine people killed.

Following these disturbances six anarchists were arrested and sentenced to long terms of imprisonment and hard labour.

To those few people willing to listen an angry Ravachol vowed to exact vengeance on behalf of the common people. Not long after the police barracks at Fourmies was fire-bombed.

On 11 March 1892, a bomb exploded at the home of the Judge who had presided at the trial of the Clichy anarchists, and it was followed two weeks later by a similar explosion at the home of the Chief Prosecutor.

Although the damage was extensive no one had been killed and Ravachol disappointed that no blood had been shed in the attacks was overheard by a waiter in a cafe he frequented planning more. Reported to the police as a suspect in the bombings Ravachol was promptly arrested and charged with arson and attempted murder.

The night before he was due to stand trial the cafe was bombed and the waiter who had reported him and a diner were killed and despite already being firmly under lock and key, he now became a suspect in their murders too.

Ravachol did not deny his guilt and was sentenced to hard labour for life but this was not enough for the Authorities who sought to make an example of him and following his conviction he was transferred from prison to his home region of Montbrison to stand trial once more this time for the murders of an elderly hermit and a former landlady, crimes of which he had long been suspected.

The evidence against him was flimsy and much of it fabricated but nonetheless the accusations were not without credence and under cross-examination he confessed to robbing Jacques Brunel, the 93-year-old Hermit of Montbrison, but denied murdering him. The 15,000 francs he stole, he said, had been spent supporting the families of imprisoned anarchists.

He also confessed to the unrelated crime of grave robbing but the death of the landlady with whom he had remained friends, he denied all knowledge of.

Even though little material evidence of his involvement in the crimes was produced he was found guilty and so just before the sentence of death was due to be passed, he tried to deliver to the Court a pre-prepared statement but was prevented from doing so. The text of his statement survived however and has since become known as ‘Ravachol’s Forbidden Speech.’

"If I speak, it’s not to defend myself for the acts of which I’m accused, for it is society alone which is responsible, since by its organization it sets man in a continual struggle of one against the other. Well then, in a society where such events occur, there’s no reason to be surprised about the kind of acts for which I’m blamed, which are nothing but the logical consequence of the struggle for existence that men carry on who are obliged to use every means available in order to live.

Let everyone scrape by as he can! What can he who lacks the necessities when he’s working do when he loses his job? He has only to let himself die of hunger. Then they’ll throw a few pious words on his corpse.

We will quickly understand that the anarchists are right when they say that in order to have moral and physical peace, the causes that give birth to crime and criminals must be destroyed. So that is why I committed the acts of which I am accused, and which are nothing but the logical consequence of the barbaric state of a society which does nothing but increase the rigor of the laws that go after the effects, without ever touching the causes.

You members of the jury, will doubtless sentence me to death, because you think it is necessary, and that my death will be a source of satisfaction for you who hate to see human blood flow; but when you think it is useful to have it flow in order to ensure the security of your existence, you hesitate no more than I do."

Ravachol was executed by guillotine on 11 July 1892.

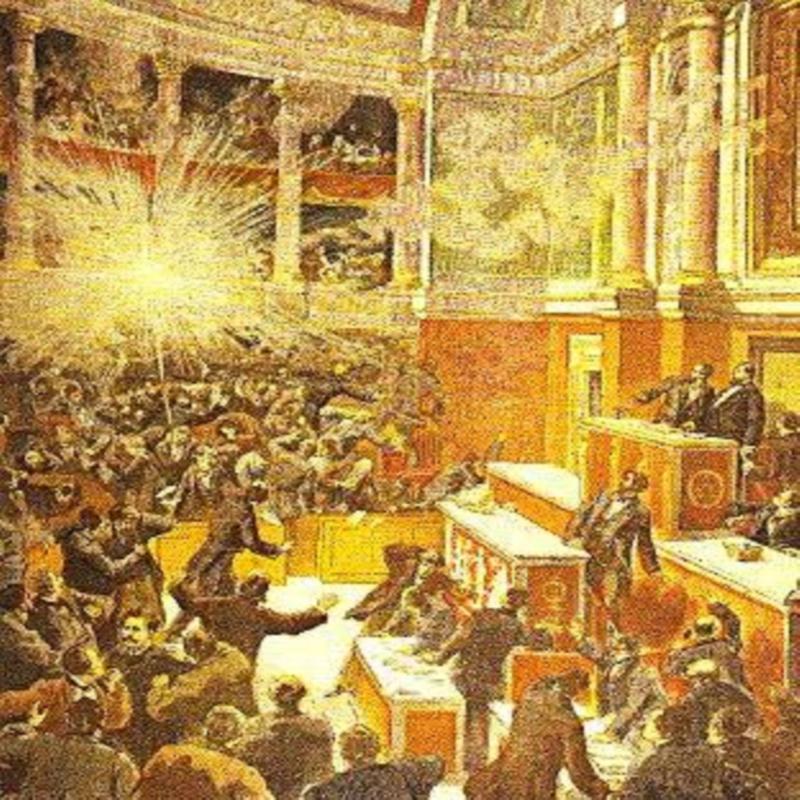

Auguste Vaillant worn down by years of extreme poverty rose briefly from obscurity to a position of national prominence when on 9 December 1893 he threw a home-made bomb from the public gallery of the French National Assembly.

It was a weak device that did little damage and Vaillant, who was arrested at the scene, would later claim that it was never his intention to kill or seriously harm anyone but merely to protest the unjust execution of Ravachol and the fact he was killed for being unable to feed his children.

Starvation was to prove no mitigation and a death sentence was passed regardless, and he too was executed by guillotine on 3 February, 1894.

Emile Henry was a very different man to both Ravachol and Vaillant born as he was into the very privilege he professed to hate as the son of a prosperous if politically radical family with aristocratic connections. His anarchism was learned not experienced and any hardships he endured were self-inflicted.

Outraged by what he saw as the judicial murders of Ravachol and Vaillant he determined to strike back, not at the instruments of oppression but the self-centred complacency of the bourgeois society in whose interests they operated. His wrath fixated on the many cafes that tumbled out onto the streets of old Paris, the watering holes of workers relaxing after a hard day at the office, the bank or shopping for the fripperies of life at fashionable retail outlets.

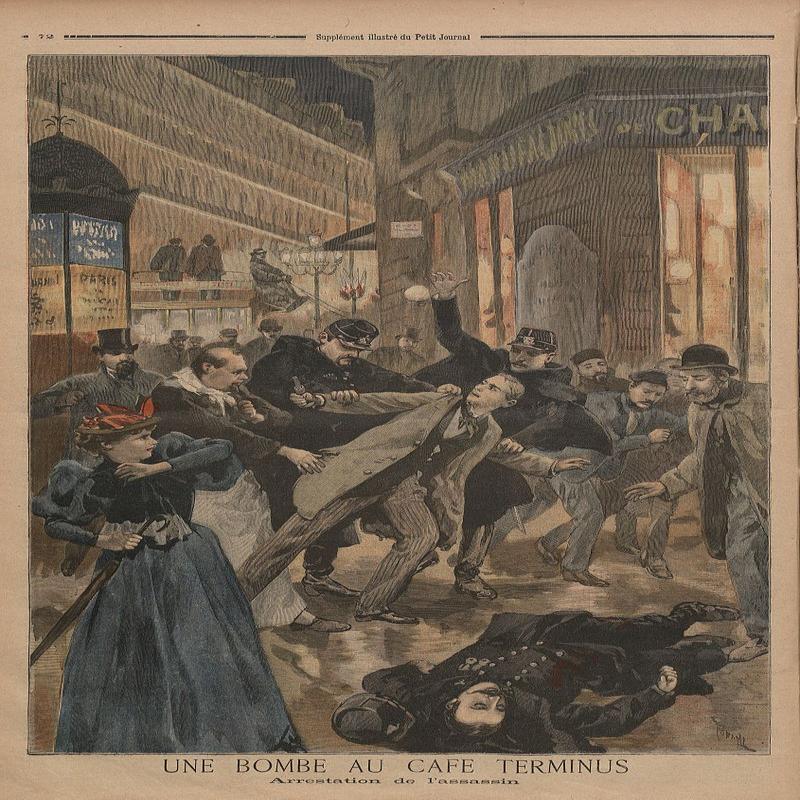

On 12 February 1894, Henry watched as the cafes began to fill with customers in need of libation and shelter from the chill wind. He soon alighted upon the busiest them of all – the Cafe Terminus in the Gare Saint-Lazare.

With a bomb concealed beneath his overcoat he ordered a beer and then another before lighting a cigar. He then made his way towards the exit before removing the bomb and using the burning cigar to light its fuse.

Despite being seen he was able to throw the bomb and rush outside as the infernal device detonated with a force so great it caused the ceiling to collapse, furniture to splinter and smashed the windows spraying those inside with shards of lethal glass.

Henry forced his way onto the street where he was pursued and despite ferocious resistance caught and overpowered. Handed over to the police he repeated many times under interrogation his disappointment that only one person had been killed in the Cafe Terminus explosion though more than 20 had been injured many seriously.

It was also during his interrogation when asked why he would want to kill innocent people merely having a drink after work he famously replied – there are no innocent bourgeoisie.

Sentenced to death he, unlike Ravachol, was permitted to address the Court:

“In the merciless war that we have declared on the bourgeoisie, we ask no mercy. We mete out death and so we must face it. I await your verdict with indifference. I know that mine will not the last head that you will sever . . . whether beheaded in Germany, garrotted in Jerez, shot in Barcelona, or guillotined in Montbrison our dead are many but you cannot destroy anarchism for its roots go deep and spout from the very bosom of this rotting society that trembles and falls apart . . . it is everywhere indomitable and will end by defeating and killing you.”

Emile Henry was executed by guillotine on 21 May 1894.

Just one month after the execution of Henry, Sadi Carnot the President of France was stabbed to death by the Italian anarchist, Sante Geronimo Caserio. He would just be the first of many.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous, Modern

Share this post: