Reporting the Charge of the Light Brigade

Posted on 28th January 2021

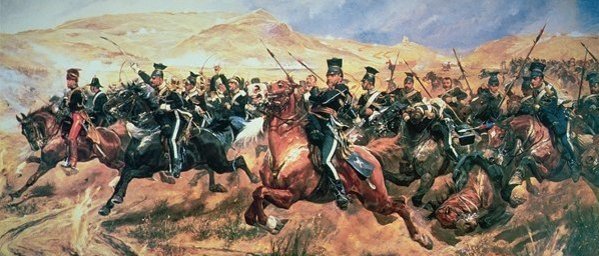

William Howard Russell was one of the first official War Correspondents who worked for both the Times Newspaper and the Illustrated London News. On 25 October 1854, he was witness to one of the most notorious blunders in military history when the Light Brigade under its commander James Thomas Brudenell, Lord Cardigan, charged the Russian guns.

The Battle of Balaclava had begun that morning with a surprise Russian attack on the Allied positions. The fighting had already begun to peter out with little progress made on either side when late in the day Lord Lucan in command of the British Cavalry received the order to capture the enemy guns. But what enemy guns exactly? The only guns visible were those at the end of a clear featureless valley and they appeared to be manned and ready to fire.

Clearly his orders required clarification but with Captain Nolan who had delivered the instructions pointing towards the guns adamant they were the ones in question and barely on speaking terms with his brother-in-law Cardigan, Lucan ordered the attack to go ahead. If it was a mistake, then his idiot brother-in-law could take the blame for it.

Russell’s watched events with a sense of disbelief and was eager that his dispatch be received in London as quickly as possible, but it would take time and it wasn’t published in the Times editorial until 13 November, but when it was it caused a sensation; a moment of the utmost courage and sacrifice had been captured in Russell’s short but vivid account. It was something of which the country could be proud. Once the details of military incompetence and foolish pride emerged however, attitudes would modify somewhat towards those in charge but that the Light Brigade, were heroes would never change:

“They swept proudly past, glittering in the morning sun in all the pride and splendour of war. We could hardly believe the evidence of our senses! Surely that handful of men were not going to charge an army in position? Alas! it was but too true - their desperate valour knew no bounds, and far indeed was it removed from its so-called better part - discretion.

They advanced in two lines, quickening their pace as they closed towards the enemy. A more fearful spectacle was never witnessed than by those who, without the power to aid, beheld their heroic countrymen rushing to the arms of death. At the distance of 1200 yards the whole line of the enemy belched forth, from thirty iron mouths, a flood of smoke and flame, through which hissed the deadly balls. Their flight was marked by instant gaps in our ranks, by dead men and horses, by steeds flying wounded or riderless across the plain.

The first line was broken - it was joined by the second, they never halted or checked their speed an instant. With diminished ranks, thinned by those thirty guns, which the Russians had laid with the most deadly accuracy, with a halo of flashing steel above their heads, and with a cheer which was many a noble fellow's death cry, they flew into the smoke of the batteries; but here they were lost from view, the plain was strewed with their bodies and with the carcasses of horses. They were exposed to an oblique fire from the batteries on the hills on both sides, as wed as to a direct fire of musketry.

Through the clouds of smoke we could see their sabres flashing as they rode up to the guns and dashed between 'them, cutting down the gunners as they stood. We saw them riding through the guns, as I have said; to our delight we saw them returning, after breaking through a column of Russian infantry, and scattering them like chaff, when the flank fire of the battery on the hill swept them down, scattered and broken as they were.

Wounded men and dismounted troopers flying towards us told the sad tale. At the very moment when they were about to retreat, an enormous mass of lancers was hurled upon their flank. Colonel Shewell, of the 8th Hussars, saw the danger, and rode his few men straight at them, cutting his way through with fearful loss. The other regiments turned and engaged in a desperate encounter. With courage too great almost for credence, they were breaking their way through the columns which enveloped them, when there took place an act of atrocity without parallel in the modem warfare of civilized nations.

The Russian gunners, when the storm of cavalry passed, returned to their guns. They saw their own cavalry mingled with the troopers who had just ridden over them, and to the eternal disgrace of the Russian name the miscreants poured a murderous volley of grape and canister on the mass of struggling men and horses, mingling friend and foe in one common ruin. It was as much as our Heavy Cavalry Brigade could do to cover the retreat of the miserable remnants of that band of heroes as they returned to the place they had so lately quitted in all the pride of life.

At twenty-five to twelve not a British soldier, except the dead and dying, was left in front of these bloody Muscovite guns."

Share this post: