Rob Roy MacGregor: A Highland Legend

Posted on 8th June 2021

The name "Rob Roy" is one that epitomises the image of the Highlander as the free-spirited man strong and brave who much-like Robin Hood or the Cowboys of the American West has been romanticised by history. But the truth was very different.

Robert Roy MacGregor was born on 7 March 1671 at Glengyle on the banks of Loch Katrine in Stirlingshire. His father Donald Glas was a prominent member of the MacGregor Clan but not it’s Laird.

The MacGregor's were notorious reivers, or thieves and were much feared for their violent behaviour and rarely it was said did they not demand satisfaction for the slightest slur on their honour. Indeed, so hated did the MacGregor's become that by the time of Robert's birth the mere mention of their name had been banned.

His father made his money from cattle rustling and as a dutiful son Robert would have been expected to support his father in his criminal endeavours but also as the son of a leading Clan member, he would have received an education, and we know he could both read and write and speak English as well as his native Gaelic. He was never less than articulate in his correspondence and it was evident that he was more than capable of making his living within the law, if he had chosen to do so.

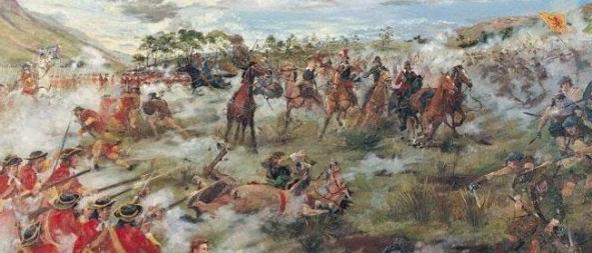

At the age of eighteen he joined his father in the Jacobite Rebellion against King William and fought at the 1689 Battle of Killicrankie, a bloody affair that despite being a Jacobite victory was to leave more than 600 Highlanders dead including their leader the Bonnie Dundee.

Without Dundee to lead them the rebellion soon lost its way and many Highlanders simply returned home despondent that not for the first time their sacrifice had been in vain.

A few months later Robert's father was captured while on a cattle rustling raid and imprisoned for two years with a charge of High Treason hanging over his head. Whilst in prison his wife died, and this seemed to break the spirit of the old man and upon his release he agreed to sign the Oath of Allegiance to King William. Even so, the Privy Council in Edinburgh demanded that he cover the costs of his captivity but not having the money to do so it became Robert’s responsibility to raise the money by stealing cattle. On one such raid he killed a man who refused to hand over his livestock.

On 1 January 1693 Robert married his cousin Helen Mary MacGregor. It appears to have been a happy marriage and they were to have four children, all of whom were to live into adulthood.

Having attained some land near Loch Lomond which he merely occupied and had no legal right he continued to augment his meagre income rustling the cattle of his neighbours and by running a protection racket known as the "Lennox Watch." Local farmers who did not want their cattle stolen and be beaten up or worse paid him rent. By these means he assiduously built up his cattle herd, few if any of which had been paid for and over the next few years, he acquired the reputation of a respected if not entirely trusted businessman.

A tall, well-built man with unusually long arms who had a fiery temper and saw a violent response as the solution to any dispute the respect was grudging, and no doubt borne out of fear rather than admiration. His mane of wild, unkempt red hair earned him the name Red Robert, later revised to Rob Roy, only enhanced his violent reputation and few men were willing to dispute with him.

His life began to unravel in 1712, however, when he decided to increase his cattle herd by borrowing a large sum of money, as much as £1,000, from James Graham, Duke of Montrose.

Highlanders were ill-considered by most of their fellow Scots, they spoke an alien tongue - Gaelic, lived within a system of Clan loyalty based upon blood ties and were wedded to the old Catholic religion. Lowland Scotland, the commercial hub of the country, viewed with scorn the violent men of the North who were little better than savages. They had more in common with their Protestant English neighbours to the South with whom they did business. This did not prevent them from trying to exploit those they considered uneducated and ignorant, however.

Loans for example would often be made available at rates of interest which were difficult to sustain and so provided the opportunity to seize both land and property with the full weight of the law. When his Chief Cattle Herder absconded with the money, Robert was forced to default on the loan.

The Duke of Montrose was typical of a Scottish Nobility that were considered even more haughty and out of touch with the common people that their counterparts across the border. He was a Scot no doubt, but an Englishman once removed.

Arrogant and unsympathetic Montrose refused to listen to Mac Gregor’s excuses and in response to the default on his loan he charged Robert with embezzlement and had the Law of Sword and Fire passed on him.

It is likely that Rob Roy never truly intended to repay the loan given the vast amount that he had borrowed, and it is equally as likely Montrose never expected him to. He had more than once expressed the view that Robert MacGregor was a scoundrel and a rogue yet he had loaned him the money nonetheless. They were playing a game of bluff, one with his property the other with his life.

Montrose had his men evict Robert's family from their home at Inversnaid which was then burned to the ground and in the process, it is believed they also raped and branded his wife.

His land was then seized, and his livestock sold. Rob Roy was now a man on the run, but he would not run far. Instead, he undertook a campaign of vengeance against the hated Montrose. His properties were attacked, his goods destroyed, his moneymen robbed and killed, his cattle stolen. It drove the ever more desperate Montrose by now fearing for his own life to place a price on Rob Roy's head, and he was to spend a small fortune to those who promised to bring him in either dead or alive. But even when he was captured, as at Balquhidder in 1722, he promptly escaped.

Likewise, when he was tricked into surrendering himself to the Duke of Atholl he bribed his guards and escaped before he could be handed over to Montrose. It was also during this period that he fought and killed a number of those in Montrose’s pay in well publicised duels.

Montrose's desire for recompense could never compete with the Highland code of honour and as a leading proponent of the Act of Union of 1707, for which he had been elevated to the Dukedom, Montrose had better things to do than pursue a Highland rebel with blood on his hands and murder in mind.

The two men were never reconciled but Montrose poured water on the fires of revenge by feigning indifference and MacGregor was permitted to remain at liberty.

Always an unrepentant Jacobite he participated in the uprising of 1715 and was duly placed on a list of those wanted for High Treason. He later accepted the amnesty that was on offer, but this didn't prevent him from again fighting for the Jacobite cause at the Battle of Glen Shiel in 1719 where he very nearly died from wounds. Captured once again in 1722 he was taken to and imprisoned in London for five years before being pardoned by King George II.

Rob Roy, as he was by now known without affection, was a thief, a liar, a braggart and a bully but his courage was never in doubt, neither was his loyalty to his Clan, his Catholic faith or his commitment to the Jacobite cause. He had also stood up to and humiliated the hated Montrose.

When he returned to Scotland in 1727, it was as a hero of his Clan, and he was able at last to settle down to a quiet life enjoying both his wealth and his fame. He died peacefully in his bed at Inverlochlarig Beg on 28 December 1743, aged 63.

The story of Rob Roy was revived, his reputation enhanced and his place in history assured following the publication of Sir Walter Scott's popular novel of the same name in 1817.

Tagged as: Georgian

Share this post: