Robert the Bruce: Spirit of Scotland

Posted on 3rd May 2021

On 19 March 1286, after a tiresome day at Edinburgh Castle attending to state affairs the 44-year-old Alexander III, King of Scotland expressed an overwhelming desire to be with his 17 year old wife Yolande but she was some 30 miles away in Fife.

The night as dark, a storm was brewing and the weather already foul could only get worse. Any journey would be a perilous undertaking in such conditions, and he was advised not to travel but he was eager to make coitus with his fecund young bride regardless of any other considerations.

He journeyed with an entourage of course, but in the darkness and deafened by the howling wind he became separated from his companions. The exact details of what happened, next remains a mystery but the following day his body was found at the bottom of some cliffs. It appeared that his horse had stumbled, and he had plunged to his death.

The King had left no surviving children and so the next in line to the throne was his granddaughter the six-year-old Margaret, Maid of Norway. She had already been promised in marriage to King Edward I of England’s eldest son the Prince of Wales but when she died enroute to Scotland four years later in mysterious circumstances the whole issue of the succession descended into chaos.

There were any number of claimants to the Scottish Throne but only three real contenders – the elder Bruce, John Balliol and John Comyn. Of these the Bruce family were particularly aggressive in pursuit of their claim and had already led a rebellion against the recently deceased Margaret and in the eighteen year old Robert they possessed a man who was certain the Scottish Throne was his by right.

He did indeed have a legitimate claim as the fourth great-grandson of King David, but it was by no means the strongest claim and for the time being at least it would be his aged grandfather who would claim the throne for the family.

To rid themselves of the impasse of so many contending claims and the prospect of conflict between them the Guardians of Scotland approached King Edward to act as arbiter and his decision based upon the evidence provided by the academics was to be binding and final.

Edward I, an imposing figure at 6’2″ known without affection as Longshanks was a cunning, deceitful and ruthless man and the Scots were aware that he could not be entirely trusted but he was the only man with the authority that could guarantee a decision would be binding and so they reluctantly agreed to trust in his word.

Having weighed up the evidence and no doubt what was in his own interests on 17 November 1292 he announced that John Balliol, another grandson of King David, was to be the new King of Scotland. Thirteen days later on 30 November he was Crowned King at Scone.

It was a decision that the Bruce family were never going to accept but they had as much to lose as they had to gain and so patience became their watchword. They were willing to bide their time and over the next decade they were to change their spots many times. After all, they owned as many Estates in England as they did in Scotland and felt no greater loyalty to either country than they did to their own self-interests.

The young Robert was not his grandfather however, and over time he came to associate his own and his family’s interest very firmly with that of his homeland. Edward saw things very differently from London. He had little interest in conquering Scotland being far more concerned with pressing his claim to the French Throne. But he did want a puppet King who would rule Scotland in his interests hence his choice of John Balliol.

Balliol was by no means a weak man but like many he found himself incapable of standing up to Edward’s volcanic rages that could intimidate the strongest of men and Edward took the opportunity to humiliate the new Scottish King. When the Scots protested at the treatment of their Monarch and asserting their independence looked to France for support a furious Edward marched North at the head of his army – he would make an example of the Scots they would never forget.

On 30 March 1296, he attacked the prosperous border town of Berwick and though many Scots fled before him there was still enough to make the slaughter great and as many as 4,000 people were put to the sword. It is said that the massacre only ceased when Edward personally witnessed the murder of a woman as she was giving birth. Berwick was then put to the torch but later rebuilt and populated with English settlers from Cumbria and the border with Scotland has run north of the River Tweed ever since.

On 29 April, the Scottish Army was defeated at the Battle of Dunbar and John Balliol forced to flee north to Perth but with no prospect of further resistance he had little choice but to surrender himself to the English King.

On 2 July, he was taken to Kincardine Castle where he admitted his treason and was made to beg for Edward’s forgiveness. A week later at Montrose he was stripped of his Royal vestments in a public ceremony by the Bishop of Durham and forced to abdicate. Thoroughly humiliated he was then taken in captivity to London and thereafter be known to the Scots as Toom Tabard, or Empty Coat.

Following King John Balliol’s abdication Edward returned to England having removed the Stone of Scone, or Stone of Destiny, upon which all Scottish Monarchs had been crowned. Along with the Scottish Royal Seal he took it back to London with him remarking as he did so, "it does one good service to rid oneself of a turd.” They were to remain in London for the next 800 years – from now on Scotland would be ruled by Englishmen.

The attitude of the Bruce family throughout these events remained ambivalent as they bent with every gust of the political wind and fluctuated between supporting Balliol and pledging their loyalty to Edward and Robert the Bruce in fact served with Edward’s Army at Dunbar.

There was no such ambivalence in the attitude of William Wallace, however.

He was the well-travelled son of a minor nobleman who had been educated in Rome and was well-versed in the arts of war having almost certainly served as a mercenary soldier while abroad. He also had a grudge against the English who had been responsible for both the death of his father Malcolm Wallace and of his wife, Marion Braidfute.

His rebellion began in the Forest of Selkirk and though he was to be a thorn in the side of the English his rebellion did not really take off until he moved north to combine with the more successful army of the Earl of Moray who was moving south from the Highlands.

On 11 September 1297, their combined force met the much larger English Army of John de Warenne, Earl of Surrey, at Stirling Bridge. The over-confident and arrogant de Warenne was to lead his army into a well-laid trap and the ensuing battle was a rout. In celebration of his triumph Wallace had a scabbard made for his sword from the flayed skin of Hugh de Cressingham, Edward’s hated Treasurer in Scotland.

The death of the Earl of Moray from wounds received in the battle a few days later left Wallace as the most powerful man in Scotland and the undoubted leader of what was becoming known as the Great Cause.

Though he had not been present at the battle it was Robert the Bruce who knighted the victorious Wallace upon his return to Edinburgh and pronounced him Guardian of Scotland. The buoyant Wallace was now determined to take the war to the English, attacking towns and villages as far south as Yorkshire.

But Wallace’s rise to prominence was resented by many of the Scottish Nobility who viewed him as an upstart, and he never really had their support. A fact that was to come back to haunt him.

Meanwhile, in London, Edward I was furious at the incompetence of his placemen in Scotland and so he would deal with this William Wallace personally and lead the army himself and so in the summer of 1298 his army reinforced by troops from Ireland, Wales, and Gascony crossed into Scotland.

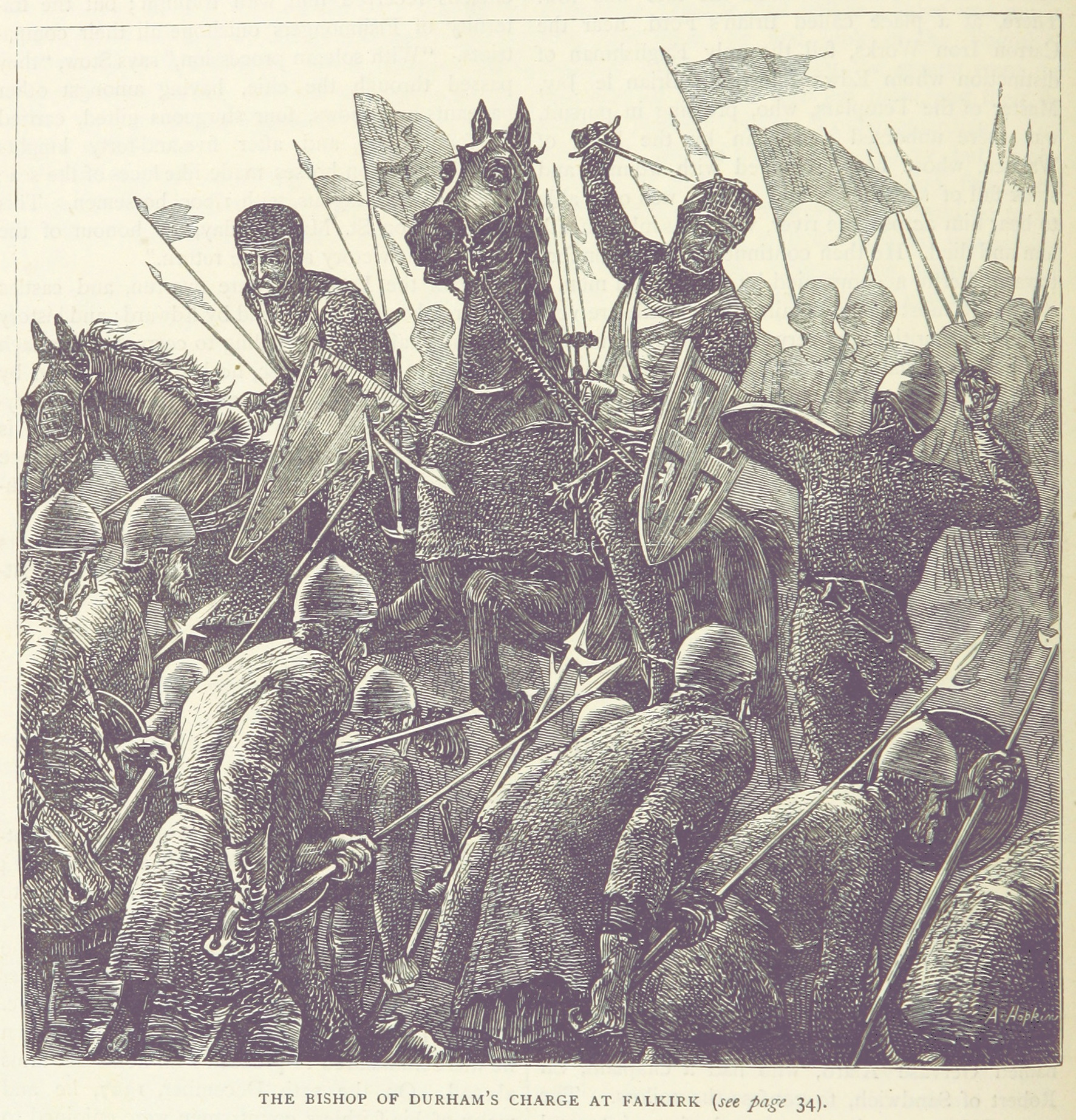

Wallace knew that to confront Edward in a set-piece battle would be foolhardy and at first adopted a successful scorched earth policy denying Edward’s Army food and shelter and harassing them at every turn; but such was his reputation as a battlefield commander that the pressure on him to confront Edward increased daily but to do so proved a mistake when on 22 July his army was utterly destroyed at the Battle of Falkirk when at the crucial moment many of the Scottish Nobles deserted his cause.

Wallace had managed to escape the carnage at Falkirk, but his reputation was damaged and in September he was forced to resign as Guardian of Scotland and though he was to continue his resistance to English rule he no longer had popular support. On 5 August 1305 he was captured by other Scots at Roybroston near Glasgow, possibly betrayed by the Bruce himself, and handed over to the English where taken in chains to London he stood trial at Westminster Hall charged with Treason. He said nothing during the proceedings except when angrily responding to the specific charge that he was a traitor: “I could never be a traitor to Edward for I was never his subject.”

It was true and unlike most of the Scottish Nobles he had never sworn an oath of allegiance to Edward, but it made no difference and on 23 August 1305, he was stripped naked, forced to wear a crown of thorns and dragged through the streets of London by a horse to his place of execution. There he was hung, drawn, and quartered. His head was preserved in tar before being displayed at Tower Bridge and his four limbs were despatched to Scotland where they were put on display as a warning to others.

With William Wallace, the great freedom fighter dead many Scots now looked to Robert the Bruce for their salvation and Edward, aware of the possibility that he might become the focus of continued Scottish resistance, ordered his arrest but warned in advance, Robert the Bruce hastily fled the English Court in London and returned to Scotland. It appeared however that his ambition to be King of Scotland might be thwarted by John Comyn.

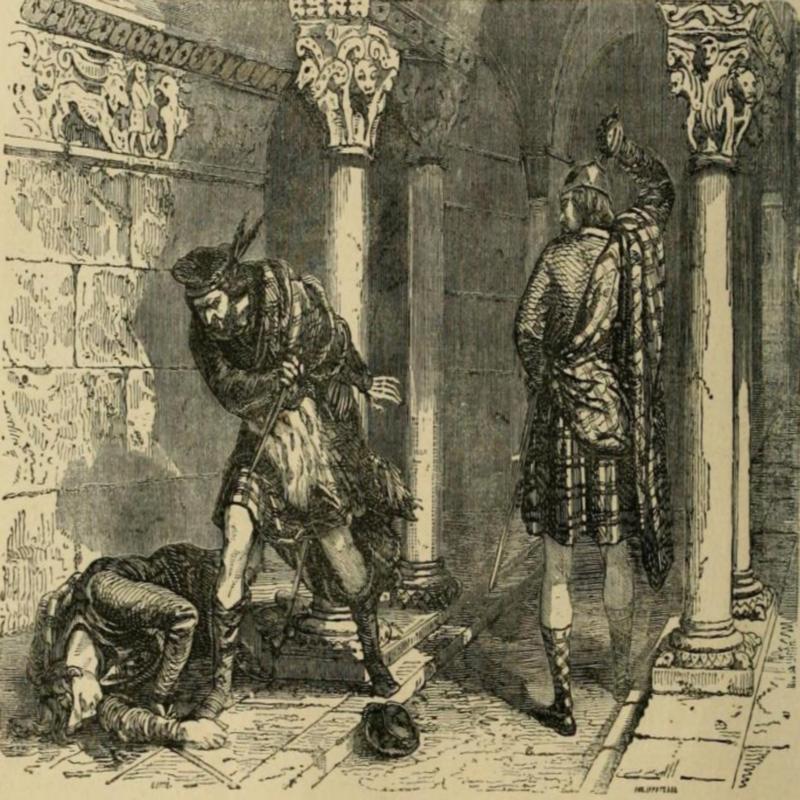

Comyn was the most powerful nobleman in Scotland and had been far more consistent in his opposition to the English than Robert the Bruce had ever been. Many also believed had a better claim legal to the throne. On 10 February 1306, they agreed to meet at Greyfriars Abbey, ostensibly to iron out their differences. Not far into their discussions an argument broke out during which Comyn accused Bruce of being a traitor. A furious Bruce responded by taking out his sword and stabbing Comyn to death.

The killing of Comyn was seen by many as being nothing more than cold-bloodied murder and it split opinion. Nevertheless, with his main rival dead Bruce was now determined to Crown himself King of Scotland which he did at Scone on 27 March 1306, but for many his rush to adopt the mantle of Kingship only served to reveal his naked ambition and most Scots now turned against him.

Although there was never an Inquiry into the events at Greyfriars, Bruce was accused of murder, excommunicated by the Pope and declared an outlaw by Edward I; later that year with few willing to take up arms in his defence he was deposed by the English and forced to flee.

A hunted man and deserted by his supporters, he spent the winter of 1306 hiding in a cave off the coast of Ireland and it was during his period in exile that the story of the spider whose relentless determination to complete its web provided Bruce with the courage to persevere first emerged.

Upon his return to Scotland, Bruce was to discover that three of his brothers had been executed during his absence and his wife and children had been imprisoned; but he had also returned no longer the polished aristocrat but a hardened guerrilla fighter with a strategy and prepared for the long-haul. Gathering support, he now embarked upon a campaign of guerrilla warfare that was dazzling in its execution and culminated in his victory at the Battle of Loudon Hill in May 1307.

Unable to rely upon his subordinates Edward, despite being sick with a fever was determined to lead one last campaign of subjugation in Scotland. But it wasn’t to be. On 6 July 1307, just south of the border near Carlisle he died. His body was taken back to London and buried in Westminster Abbey on 27 October next to that of his beloved wife Eleanor of Castile who had died seventeen years earlier. On his tomb were inscribed the words: “Hie Primus Edwardus, Hic Est Malleus Scotorum (Here Lies Edward the First, the Hammer of the Scots).”

The ferocious Longshanks was dead and would never lead his army against Robert the Bruce that responsibility would fall to his feckless, vain and homosexual son, Edward II. So worried by this prospect had the old Longshanks been that he had ordered the flesh be boiled from his bones so that they could be carried before his son’s army. Edward II revoked the order.

Whilst Edward II indulged his lover Piers Gaveston in London, Robert the Bruce proceeded to re-conquer Scotland and by 1314 only the town of Berwick and the formidable Stirling Castle remained in English hands.

Pressurised by his increasingly exasperated Barons and curtly informed by the Commander of Stirling Castle that if he did not come to his assistance then he would surrender it into the Bruce’s hands, Edward raised an army and marched north.

Edward II was as tall and as physically imposing as his father had been but there the similarities ceased, and though he was not as effeminate as he has often been portrayed and personally brave, he was also lazy, indecisive and militarily inept. His open homosexuality and flagrant disregard of their interests meant he never had the respect of his Barons.

On 24 June 1314, Edward led a 19,000 strong army on to a field near the Bannockburn, not far from Stirling Castle. Robert the Bruce’s army was less than a third of the size of Edward’s, but he had chosen his ground well and unlike the English King he knew what he was doing.

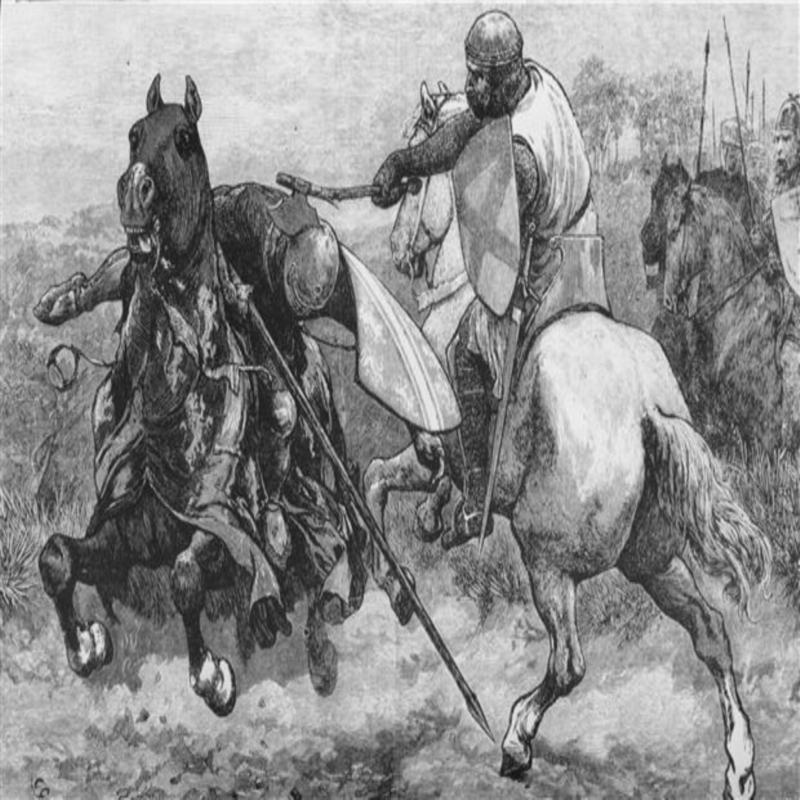

The ensuing Battle of Bannockburn was to be fought over two days, but it almost ended before it had begun when the Bruce became separated from his men. Seeing his opportunity a young English knight in the King’s entourage, Henry de Bohun, lowered his lance and charged at speed straight towards the Scottish King.

Bruce, astride a small pony and armed only with a battle-axe remained where he was but as de Bohun neared, he moved his pony to one side and split the young knights head open with a single blow of his axe. He had survived but it had been a close-run thing. Berated by his Senior Commanders for his recklessness he only bemoaned the breaking of his favourite axe.

Bruce had deliberately chosen the Bannockburn knowing that the boggy ground would impede Edward’s mounted knights and he had also been provided with the time by the English King’s reticence to do anything other than enjoy his entertainments to lay traps.

Prior to forming up his army into tightly knit schiltrons protected by 14-foot pikes he hid a number of troops in nearby woods out of sight of the English.

Edward seeing the Bruce’s army formed up ordered his cavalry forward, but they could not attack at pace through the boggy ground, neither could they penetrate the hedgehog of pikes, and the first day of fighting long and arduous though it was ended in stalemate, but Edward remained confident of victory on the morrow. After all, the Bruce had shown no inclination to emerge from behind his defensive formation and therefore posed little threat to the much larger English Army whose ultimate victory could only be a matter of time. But overnight rain was to make the ground even more treacherous and much of it was now flooded.

The following morning, Edward ordered his cavalry to advance once more but they could make no more progress than they had the previous day and broiling with frustration Edward now sent forward his infantry but weighed down by their armour they soon began to flounder in the mud and chaos reigned as they got caught up with the retreating cavalry.

Witnessing the confusion in the English ranks Bruce ordered his infantry, still in formation, to advance as those troops he had hidden in the woods attacked from both flanks. Edward was at a loss at what to do as he watched his army fall apart and panicking fled the field turning what had been a retreat into a rout and by the end of the battle 4,000 English, Welsh, and Gascon soldiers lay dead along with 700 knights and men-at-arms. Some 500 Scots had been killed but on the banks of the Bannockburn Scottish independence had been reborn.

Following his defeat, Edward did not relinquish his claim to over-lordship in Scotland and military incursions were to continue for a number of years. As a result, Bruce decided that he needed international recognition of Scotland’s existence as an independent State and what transpired was the famous Declaration of Arbroath. It was written as a letter to Pope John XXII on 6 April 1320 and was unequivocal in its declaration of sovereignty: “For as long as but a hundred of us remain alive, never will we on any conditions be brought under English rule. It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honour that we are fighting but for freedom – for that alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself.”

Recognition of Scotland as a sovereign State with Robert the Bruce as its lawful King, duly followed.

In 1315, Robert sought to create a broad anti-English Gaelic Alliance and sent an army to Ireland under the command of his brother, Edward. With him he took a letter of introduction, the Nostra Nacio (Our Nation):

“Whereas we and you and our people and your people, free since ancient times, share the same national ancestry and are urged to come together eagerly and joyfully in friendship by a common language and common custom, we have sent you our beloved kinsman, the bearer of this letter, to negotiate with you in our name about permanently strengthening and maintaining inviolate the special friendship between us and you, so that with God’s Will our nation may be able to recover her ancient liberty.”

It was a bold strategy designed to isolate England and encourage both the people of Ireland and Wales to assert their own independence, but the timing of the campaign could not have been worse. Months of incessant rain, unusually cold temperatures and frosts had destroyed crops and guaranteed a failed harvest. Indeed, it was one of the worst famines to hit Europe for many decades and armies have to be provisioned and fed.

The Scots, who had initially received a warm welcome particularly in Ulster where Edward Bruce had even been crowned High King of Ireland soon began to outstay their welcome and as they moved south, they began to meet resistance. Town gates were locked to them, farms in their path were abandoned and the livestock removed whilst Irish bandits harassed the Scottish baggage train.

What the Scots Army required they now simply took from the local population and those who refused to hand over their livestock were killed. Soon both the Irish people and the Scots were close to starvation, and it seemed as if the Scottish presence in Ireland was no blessing but a curse. When at the Battle of Faughart on 14 October 1318, the Scots were defeated by an Anglo-Irish Army and Edward Bruce killed the entire country breathed a sigh of relief. It was written that: “Edward Bruce was the common ruin of the Gaels and Galls of Ireland, never a better deed was done for the Irish than this.”

Robert the Bruce’s dream of creating a pan-Gaelic Alliance and opening up a second-front against the English had ended in failure and he was forced to fall back on the Scots ancient alliance with France which committed Scotland to come to the assistance of the French in any future war with England, something he had hoped to avoid. Nevertheless, the Auld Alliance was renewed in 1318.

On 21 September 1327 Edward II was murdered on the orders of his wife Isabella, by a red-hot poker thrust up his rectum, and with his death English incursions into Scotland ceased.

In May 1328, the new King Edward III signed the Treaty of Edinburgh and Northampton which recognised Scotland as an Independent Nation with Robert the Bruce as its lawful King. He had secured Scottish freedom and as he saw it, forever. It was a personal triumph for The Bruce, but it was to be his last.

Robert the Bruce died on 7 June 1329, aged 54, at Cardross Manor near Dumbarton of what was described as an “unclean ailment” believed to have been leprosy, a disease that had also afflicted his grandfather.

His body was buried at Dunfermline Abbey, but he had first insisted before his death that his heart must be removed and taken on Crusade as penance for his murder of John Comyn in Greyfriars Abbey all those years before - it no further than Spain.

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval, Monarchy

Share this post: