Salem Witch Trials

Posted on 5th January 2021

Thou Shalt not Suffer a Witch to Live

(Exodus 22:18)

In the early months of 1692, one of the most notorious cases of mass hysteria broke out in the villages and towns of New England in America. What they experienced was not a new phenomenon but one that had reached its zenith on the Continent of Europe more than two hundred years before - it was a Witch Hunt. At a time when the very existence of witches had become a matter for doubt and juries in England were increasingly reluctant to convict in cases of supposed maleficium, the American colonies succumbed to a paranoia not seen since the Middle Ages or the worst excesses of the English Civil and Thirty Years War.

The events in Salem can trace their origins back to the Old Country when on 6 September 1620, 102 passengers boarded the ship Mayflower at Southampton bound for the New World. The voyage was undertaken by Puritans, followers of a particularly strict brand of Protestant Calvinism. They had earlier settled at Leiden in the Netherlands but disliked the religious corruption they found there just as much as the heresies they believed they had fled in England They wanted to escape what they saw as religious persecution and petitioned King James I for relief, who, though he had little time for religious fanatics of any devotional hue reluctantly granted them a Royal Charter to establish a colony on the Atlantic coast of America. He did so, if only to be rid of them.

Arriving off Cape Cod in early November the colony they established was to be known as New Plymouth. Over the next few decades thousands more were to follow, many of them not Puritans at all, but just people who wanted to make a better life.

The central tenets of Puritanism were unforgiving. They believed in God's authority over all human affairs. His will, as expressed in the Bible was to be taken literally and a Puritan's mission in life was to commit to God's bidding in all things, and in doing so achieve moral and religious purity. They were then involved in the ever-present struggle against sin, and the harbinger of sin was Satan against whose wicked temptations they were in frequent conflict as they sought only God's Grace.

They also held to the Calvinist doctrine of Predestination, or that a person’s spiritual fate had already been predetermined by God even before they were born. No act of piety, personal charity, or commitment to the religious life could alter what had already been determined. The Puritan could never know if they had been chosen for salvation or not and so they lived in constant fear of straying from the path of righteousness and being led into the legions of the damned. Witchcraft and demonology for them was a very real and present danger. Satan and his familiars stalked the earth and had to be both exposed and eradicated wherever they were found, and whoever they may be.

The Church governed every aspect of daily life but as the influx to the New England colonies of people who did not share the Puritan faith continued apace the religious orthodoxy became increasingly difficult to maintain. They had wanted to create a heaven on earth, the shining city on a hill, and as such the law became ever harsher as they struggled to keep a tight rein on people's behaviour. Non-attendance at Church was frowned upon and forms of entertainments such as singing, dancing, gambling, and the theatre were banned. It was also not permitted for children to have toys, especially dolls which were thought to be graven images.

Salem Town had been established in 1626, and soon became a prosperous and thriving port. Salem Village, where the witch hunt was to begin, was some six miles distant from the town itself and developed over the corresponding years from a series of scattered farms into a more cohesive unit, being permanently settled in 1636.

Salem Village, unlike it prosperous near-neighbour, clung onto existence by its fingertips. It was isolated, constantly fearful of Indian attack, and riven by land disputes. It was a paranoid, disputatious, and quarrelsome place. Its Royal Charter had been withdrawn in 1684, and those who owned property were uncertain if they still had the right to it. It made for an unhealthy atmosphere and a dog-eat-dog environment. The people of Salem Village feared their neighbour more than they did an outbreak of the plague or the failure of their crops.

To distance themselves from the more liberal and often overbearing Salem Town and to assert greater control over their own affairs, the residents of the village sought to appoint their own Minister; and they were to appoint three in relatively quick succession, James Bayley, George Burroughs, and Deodat Lawson, though none were to remain but for a few years. It seemed that the villagers were even incapable of agreeing who should tend to their spiritual needs, or at least who should pay them. Eventually, they decided upon the 36-year-old Samuel Parris, a man of inherited, if limited, wealth, and an enthusiastic lay preacher who had turned to the Ministry to secure his financial future. Even then, his appointment was not universally accepted. Some disliked his perceived arrogance, whilst others objected to his apparent displays of luxury, such as having gold candlesticks in the Meeting House. Nevertheless, he became Salem Village's first formally ordained Minister in June 1689.

It soon became apparent that Parris had no talent for compromise. He was a meddlesome man, quick both to condemn and to take sides. Rather than act as a unifying force in the community he was both partisan and divisive. Condemnatory in his sermons he actively sought out "Iniquitous Behaviour" and demanded public penance for the merest infraction of the rules.

In the early months of 1692, Betty Parris, the 9-year-old daughter of the Reverend Samuel Parris, and her 12-year-old cousin Abigail Williams, began to act strangely. They screamed, they mumbled to themselves under their breath, they threw things around, and they hid under tables and in closets. When Betty seemingly fell into a trance and refused to wake, the Reverend Parris requested that the local doctor, William Griggs, attend upon the children but he was unable to find any physical ailment and declared that they must be possessed by some demon or other. Soon after other young girls began to display similar symptoms and Church meetings would be disrupted by these girls screaming that they could not listen to the word of God being preached, that they were being pricked, and pinched, and scratched by an unseen presence.

The Reverend Parris immediately suspected witchcraft and demanded to know of his daughter, his niece, and the other girls, who included Anne Putnam Jr, aged 12, Elizabeth Hubbard, aged 17, Mercy Lewis, aged 17, Mary Walcott, aged 17, Elizabeth Booth, aged 18, and Mary Warren, aged 20, what had been happening?

For a time, they maintained their silence being fully aware that what they had been doing was wrong. Finally, however, they revealed that at night they had gathered to listen to the Reverend Parris's black slave Tituba, regale them with stories of her home in Barbados. She told them about voodoo magic and showed them tricks. It was even rumoured that they danced naked as if in a frenzy. An outraged Parris, ignoring Tituba's pleas of innocence is believed to have beaten a confession out of her.

A near-neighbour of the Reverend Parris, Mary Sibley, who had become aware of events, had her servant bake a Witches Cake. Tradition had it that once consumed the good magical cake, which included among its ingredient’s urine from the afflicted girls, would expose the Witch in their midst by making her cry out in pain. Mary fed it to her dog, but nothing happened. Learning of this the Reverend Parris castigated Mary in Church. No magic, he said, was good magic. It was all the work of the devil. He acknowledged however that she meant no harm and was forgiven.

On 25 February 1692, Abigail Williams and Betty Parris accused a 39-year-old local woman Sarah Good of being a witch.

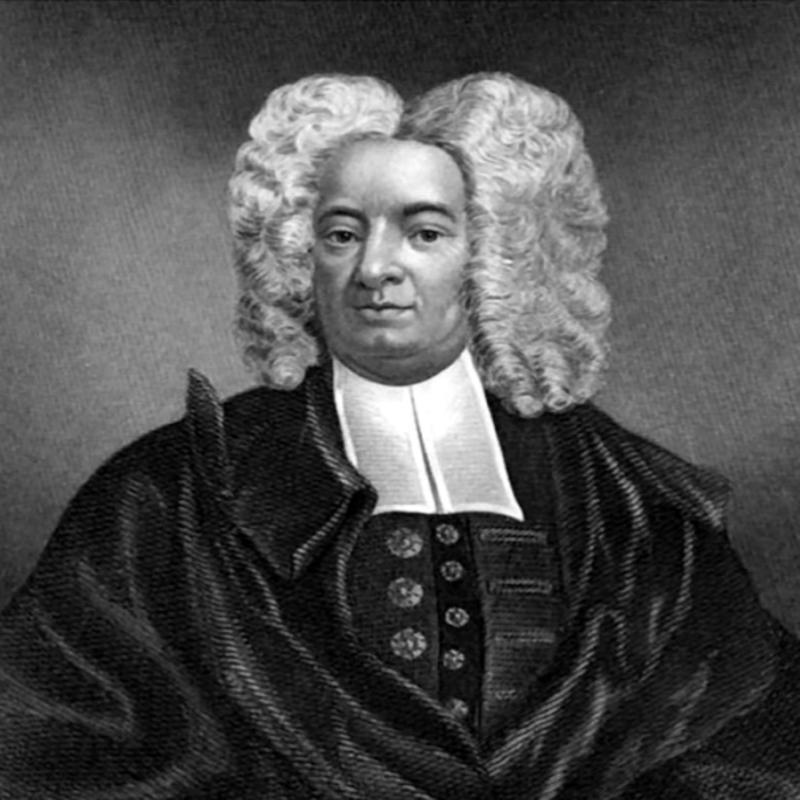

Witch Trials were not unknown in New England. There had been twelve recorded episodes of women being put to death for witchcraft since 1648. Indeed, the Boston Minister Cotton Mather had written in detail about the case of Goodwife Glover. She had been the mother of a servant in a household with four young children and had been accused of similarly bewitching them. Mather, who investigated the case, explained the methods witches used in his widely circulated book Memorable Providences. The children had been cured, it was believed, through fasting and prayer, and Goodwife Glover tried and put to death. But Mather's book was to have far greater repercussions than even he might have imagined in the response to events in Salem, even though the circumstances were to be very different.

Since the withdrawal of the Royal Charter in 1684, there had been no formal government in Salem and as such it was not possible to establish a legally recognised Court. Despite this the Reverend Parris demanded that the accused Sarah Good be made to answer to the accusations made and so depositions were taken, and hearings arranged.

There were tried and trusted ways of discovering who was a witch, and rules as to how to deal with them. In 1484, Pope Innocent III had declared witchcraft a heresy punishable by death. He then commissioned two Dominican Friars, Heinrich Kramer, and Joseph Sprenger to investigate witchcraft, how to recognise a witch, and how they were to be punished. They had concluded that women were naturally lustful and so being more vulnerable to Satanic seduction, as with Eve in the Garden of Eden. Their instructions on how a Witch, or more specifically a female Witch was to be dealt with were laid out in the book Malleus Maleficarum, or The Hammer of the Witches.

A Witch would carry the Devil's Mark, this could be a skin blemish that was believed to seal the compact between the Devil and the Witch and were often looked for in hidden places such as beneath the eyelid or under the armpit and could be scars, moles, or birthmarks, or they would have the Devil's Teat. This was believed to be an extra nipple upon which Satan's familiars suckled. Spots and warts would be pricked with pins. If they did not bleed or the accused showed no pain, then this spot was assumed to be the Devil's Teat and they were a witch.

To find the incriminating marks the accused Witch would be stripped naked and have all their body hair shaved including their genital area. Often, when entering the room, they were made to walk backwards so that they were unable to cast spells upon their accusers and interrogators with maleficent effusions from her eyes. Their naked bodies would then be inspected, and poked and prodded for signs of their guilt. If there was no obvious physical manifestation of their compact with the devil, then there were others means of establishing their guilt. Swimming was a common method. The accused Witch would be bound and immersed in a lake or river. Water was considered to be pure and would reject evil, so if the witch drowned, they were innocent. If they floated and survived, then they were guilty and would be put to death.

Kramer and Sprenger had also specified that torture was a valid means to elicit a confession. A particularly common torture was the Strappado. The accused would have their hands bound behind their backs and then be suspended in the air by means of a rope attached to their wrist and raised by a hoist. There they would remain for hours, and the pain was excruciating. Being accused as a witch then, was a fearful prospect.

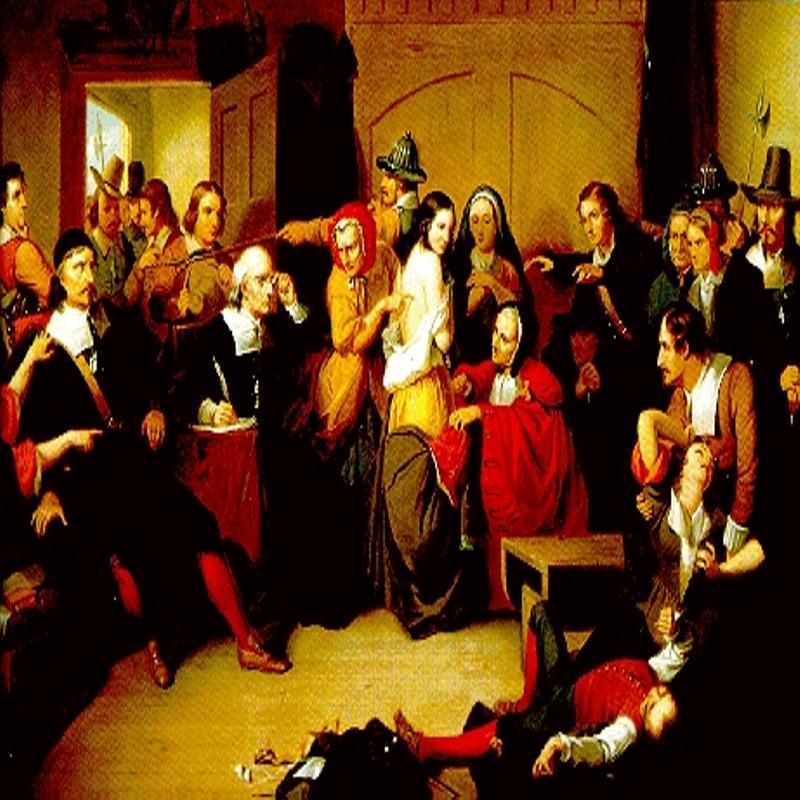

On 2 March, three women appeared before local Magistrates John Hathorn and Jonathan Corwyn at Salem Village Meeting House accused of witchcraft. They were Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne, who had also since been accused of witchcraft by the girls, and the slave Tituba. These preliminary hearings had been established to see if there was a case to answer.

Before the proceedings began the Magistrates made a decision that was to have profound consequences for the defendants. They permitted the use of spectral evidence; this was testimony from the victims that they received visitations from the witch in another form, that her spirit could attack them even when the witch herself appeared to be elsewhere. No further proof was required of this but the word of the victim.

The 39-year-old Sarah Good was a homeless beggar who was despised locally for being filthy, foul-mouthed, and irascible. She would spend her days going from house-to-house and farm-to-farm begging for food and shelter. If either were denied her, she would leave mumbling foul threats and curses under her breath. If the Magistrates thought she would be cowed by their presence, they were mistaken. She was to defend herself vigorously and deny the allegations against her of being a witch as absurd. Questioned at some length, she denied that she was a witch or had ever been a witch. She denied harming the children or ever having sent others to harm the children. When asked about the curses she frequently mumbled in the presence of others she said that they were not curses but that she was saying aloud the Ten Commandments, though when she was asked to recite them in Court she could not remember a one.

Anne Putnam Jr, had earlier sworn that the spectre of Sarah Good had tried to enlist her as a witch by getting her to sign the Devil's Book, and went onto say: "I saw the apparition of Sarah Good which did torment me grievously. She did prick me most grievously and urged me to sign the book."

Sarah again denied the accusation and dismissed them as nonsense but at her every denial the girls would become convulsed with hysteria accompanied by screams of pariah Osbourne. She had already been marked out for scorn in the community for having previously married her indentured freedman. She was also involved in a legal dispute with the Putnam family. Though she and Sarah Good were very different women they did share two things in common, they were both outsiders in the community and neither attended Church. Sarah Osbourne also denied the allegations made against her, though with less assertiveness than Sarah Good.

Finally, the Reverend Parris's slave Tituba, whose behaviour with the children, the dancing, the making of dolls, the magic tricks, and the casting of spells, had so offended the religious mores of Salem Village took the stand. Her testimony was to shock those present and push a community already teetering on the verge of paranoia over the edge.

Under questioning Tituba immediately confessed to being a witch saying: "The Devil came to me and begged me serve him."

She described how she would go on night-time excursions and flights on broomsticks, how she could talk to animals, and of her spectral visits when she would harm the children. There is little doubt that she was telling the Court what they wanted and expected to hear. After all, she was a slave no one was going to defend her. But then she dropped a bombshell, going on to describe how a mysterious tall man from Boston had visited her and bade her sign the Devil's Book. She had seen two names in the book, those of Sarah Good and Sarah Osbourne, but there were six others whose names she could not see. Upon hearing this, those in the courtroom gasped. There were at least six other unknown witches in the hallowed territory of Salem Village. There may even be more.

More accusations of meleficium followed in short order as the people of Salem Village began denouncing their neighbours. But the most accusatory of all, remained the children.

On 23 March, Rebecca Nurse was arrested on evidence provided by Edward and John Putnam. Her arrest sent shockwaves through the village. At 71 years of age, the matronly Nurse, was not only a pillar of the local community but also a fully Covenanted member of the Church, or one whom it was assumed was of unimpeachable moral character and had reached the required state of salvation. Indeed, so shocked were some people at the accusations made against her that 36 of them signed a petition testifying as to her good character, a dangerous thing to do in the situation developing.

Nurse, bent-double and profoundly deaf, had to be helped into the courtroom. In response to the accusation of witchcraft her sense of Puritan guilt sprung forth as she replied: "I am as innocent as the child unborn, but surely, what sin hath God found in me un-repented of, that he should lay such an affliction upon me in my old age."

She denied ever-knowingly to have been a witch, but her every denial was once more met by the shrieks and screams of the girls, and in particular, Anne Putnam. She claimed that she and the others were being attacked by the spectre of Rebecca Nurses. The Magistrates deemed that she had a case to answer and like the other women before her she was led away in chains to prison to await trial in the future.

The following day, Dorothy Good, also known as Dorcas, the 4-year-old daughter of Sarah Good, was questioned. She confessed to being a witch, though it is thought she only did so because she wanted to be with her mother in prison. She was so tiny that her wrists and ankles slipped through the manacles and special chains had to be made for her.

Around the same time a warrant for the arrest of Martha Corey, another fully Covenanted member of the Church was issued. She did not believe in the existence of witches and had publicly expressed her doubts about the validity of the girl’s testimony. In fact, she had called them liars. As soon as the girls heard about this, they accused her of being a witch. When her husband, the 82-year-old Giles Corey, objected, he too was accused and arrested.

At the examination of Martha Corey, the girl’s behaviour became even more bizarre. When the accused coughed, they would all cough, when she moved her head to the right or to the left, they would do likewise, and if she raised her hands in the air they all did the same simultaneously. Whenever Goodwife Corey was seen to bite her lip the afflicted would scream and claim that they too had been bitten and would show the bite marks on their arms to the Magistrates. This they would continue to do in future trials.

In April 1692, a further 36 warrants for arrests were issued and they continued apace throughout the month of May as neighbour continued to denounce neighbour. Soon the girl’s accusations and those of others had spread beyond Salem Village and into nearby towns of Ipswich, Andover, Gloucester, and even as far away as Boston itself.

With a new Royal Charter having been issued in May 1692, it was now possible to undertake formal legal proceedings against the accused and with the prisons of Salem Town and beyond by now holding close to 200 people suspected of witchcraft, the Governor of New England William Phips established a Court of Oyer and Terminer, or To Hear and Determine.

The Court of Oyer and Terminer opened in Salem Town on 2 June 1692, and was presided over by the Deputy-Governor William Stoughton, a grim, humourless man, and avowed hater of witchcraft and all those who served the evil machinations of Satan. The Court was hardly impartial, and the accused were presumed guilty before they stood trial.

Once in the Courtroom they were not only faced with the hysterical behaviour of the girls, who would scream, and shriek, and roll about as if having been attacked, but also by the hostile crowd in attendance who were not shy of displaying their anger in the vilest way spitting at the accused, and verbally abusing and hurling objects at them.

The accused brought before the Court of Oyer and Terminer were charged under a statute passed in 1604 during the reign of King James I which prohibited, "conjuration, witchcraft, and dealing with wicked and evil spirits."

The penalty for which was death.

The defendants themselves were charged with having, "killed, destroyed, wasted, consumed, pined, and lamed," certain individuals by witchcraft. Like its predecessor in Salem Village, the Magistrates would hear spectral evidence as fact. Even though, before the Court ever sat, on 31 May, Cotton Mather, upon whose work so much of the investigations were based, though broadly supportive of the prosecutions, had warned - Do not lay more stress on spectral evidence than it will bear.

The first accused brought before the Court was Bridget Bishop. She was almost 60 years old, an outspoken and independent woman who did not dress or behave as Puritan women were supposed to. She owned a tavern in Salem Town where she permitted her customers to play shuffleboard, even on the Sabbath. Her defence was undermined by the fact that she had previously been accused of being a witch. She was also spiteful and aggressive in her testimony which did not endear her to the Court. Though she was to make it plain that she did not know those who were accusing her and had never even been to Salem Village she was nevertheless found guilty and sentenced to death. Following the verdict one of the five Judges, Nathaniel Saltonstall, resigned, so disgusted was he at the behaviour of the Court, and in particular Presiding Judge William Stoughton.

Bridget Bishop was taken to Gallows Hill in Salem Town on 10 June 1692, where she was hanged. Against popular belief none of the accused witches in Salem were burned at the stake. Such punishment had been outlawed under English law 150 years earlier. She was the first person executed because of the Salem Witch Trials. She would not be the last.

Ironically, perhaps, the one sure way of avoiding execution for witchcraft was to admit one's guilt. Puritans believed that, though they could punish according to the law, only God could punish sin. For many of Puritan belief to admit to being in league with the Devil was simply unthinkable. Also, to admit to witchcraft made you a non-person and a pariah within the community. Your property could also be appropriated leaving yourself and your family destitute. Even so, some 50 of the 200 accused did admit their guilt to avoid the likelihood of execution.

Some six weeks after the execution of Bridget Bishop on 19 July, five further women followed her to the gallows: Sarah Good, Rebecca Nurse, Elizabeth Howe, Sarah Wildes, and Susannah Martin. Sarah Osbourne had died earlier in prison on 10 May.

As she was being led to the gallows Sarah Good shouted at Judge Nicholas Noyes: "I am no more a witch than you are a wizard, and if you take away my life God will give you blood to drink."

Twenty five years later as he lay seriously ill, Nicholas Noyes was to indeed choke to death on his own blood.

At her trial Rebecca Nurse, because of her high standing within the local community, had initially been found not guilty by the Jury but such was the hysterical response of the girls to the acquittal that the presiding Judge requested they reconsider. They changed their verdict to guilty and she was subsequently hanged. Fearing that they would not receive a fair trial in Salem Town some of the accused including John Proctor and his wife Elizabeth wrote to leading Ministers in Boston requesting a change of venue. Their request was denied.

On 5 August, the Court of Oyer and Terminer, which had gone into a brief recess, reconvened to try the cases of the former Minister of Salem Village the Reverend George Burroughs, John and Elizabeth Proctor, John Willard, George Jacobs, and Martha Carrier.

It was John Proctor's scorn for the young girls and their absurd allegations that had led to his wife Elizabeth being one of the first accused. On 26 March, Mercy Lewis claimed that Elizabeth Proctor's spectre was tormenting her. William Rayment, from nearby Beverley was later to say that as she entered the Court the girls appeared to go into a trance and that he heard one of them cry, "There's Goody Proctor! Old Witch! I'll have her hung."

When some people complained saying that the Proctor's were a respectable family, and that she should not speak so, the girl was heard to reply, "How else am I to get my sport."

All six of the accused were found guilty and sentenced to hang, but Elizabeth Proctor, during her inspection for the Witches Mark, had been found to be pregnant and was able to plead her belly. As such, she was given a stay of execution and sent back to prison.

In the meantime, a petition signed by twenty of the most prominent people in Salem Town attesting to John Proctor's good character and strongly held Christian beliefs was handed into the Court. But it was too late to for any reconsideration of the verdict and made no difference to his fate.

On 19 August, John Proctor too was hanged.

As he had stood upon the gallows the Reverend George Burroughs had recited the Lord's Prayer in full and word perfect. It was widely held that a witch possessed by the Devil was unable to recite the Lord's Prayer. For the first time many of those who had previously been convinced now began to question the validity of the girl’s testimony and widespread doubts began to be expressed. Nonetheless, the Court continued its grim work.

Giles Corey, who at 82 years of age was not only possibly the oldest resident of Salem Village but one of its most prosperous and respected, was accused of witchcraft. He had always been an argumentative man and a highly litigious one who had been in many legal disputes with the Putnam family over the years. His wife, Martha, had already been arrested some weeks earlier, now he was accused by Anne Putnam Jr, Abigail Williams, and Mercy Lewis of sending his spectre to attack them. He was placed under arrest and a date set for his trial, but he refused to enter a plea.

Under English Law there could be no trial without a plea by the accused of either guilty or not guilty. However, if a person refused to enter a plea, then to ensure that they could neither evade justice nor punishment by doing so, judicial torture in the form of the "peine forte et dure," or crushing by stones, was permitted to force one to plea. This was commonly known as "Pressing" and the process was described thus:

"The prisoner shall be put into a dark chamber, and there be laid on his back on the bare floor, naked, unless where decency forbids; that there be placed upon his body as great a weight as he could bear, and more, that he hath no sustenance, save only on the first day, three morsels of the worst bread, and the second day three draughts of standing water, that should be alternately his daily diet till he died, or till he answered."

Such was the fate which awaited the elderly Giles Corey.

On 17 September, he was taken to a pit near the Courthouse, stripped naked, and laid upon the ground. There, before witnesses, six men each laid a heavy stone upon his chest and stomach.

Asked to plead, he refused to answer and remained silent throughout the process. There he was left overnight. The following day he was again asked to plead either guilty or not guilty to the charge of witchcraft. Again, he refused, demanding instead "more weight." The Court willingly obliged. On the third day of torture, he was asked to plead on three separate occasions, but each time simply repeated his demand for "more weight," and further stones were placed upon his body. A local merchant, Robert Calef, who witnessed the scene, wrote: "In the pressing, Giles Corey's tongue was pressed out of his mouth, the Sheriff with his cane, forced it in again." Finally, he cried out for the last time "More weight," and died. His chest had been crushed.”

On 22 September, 8 more convicted witches were hanged at Gallows Hill. They were Martha Corey, the wife of the recently deceased Giles Corey, Alice Parker, Mary Parker, Margaret Scott, Ann Pudeator, Samuel Wardwell, Wilmot Reed, and Mary Easty.

On the eve of her execution, Mary Easty had written a brief but poignant letter pleading for common sense to prevail: "I petition to your honours not for my own life, for I know I must die, and my appointed time is set, but the Lord he knows, that if it be possible no more innocent blood may be shed."

Unknown to Mary Easty, those who were to die alongside her were to be the last executed as a result of the Salem Witch Trials.

Robert Calef, a cloth merchant, and critic of Cotton Mather who believed that scripture and not superstition should guide the actions of goodly men at such a time wrote despairingly:

“And now nineteen persons having been hanged, and one prest to death, and eight more condemned, in all twenty and eight, of which above a third were members of some of the Churches of New England, and more than half of them of a good conversation in general, and not one cleared, about fifty having confest themselves to be Witches, of which not one executed, above a hundred and fifty in prison, and two hundred accused, the Special Commission of Oyer and Terminer comes to a period.”

On 3 October, the Reverend Increase Mather, who was one of the most respected men in Boston, the President of Harvard University, and the father of Cotton Mather, who had all along been critical of the use of spectral evidence in the trials of the accused, wrote that: "It is better that ten suspected witches should escape than one innocent person be condemned."

Governor Phips, who had been away for much of the summer conducting affairs in Maine where a war had broken out with the local Indian Tribes, returned to Boston in early October where he received Cotton Mather's report into the trials. He was dismayed and wrote:

"I hereby declare that as soon as I came from the fighting and understood what danger some of their innocent subjects might be exposed to, if the evidence of the afflicted persons only did prevail either to the committing or trying of any of them, I did before any application was made unto me about it put a stop to the proceedings of the Court."

His decision, however, may have been influenced by the rumours that his own wife was about to be accused of witchcraft by some of the girls, as also was the wife of Increase Mather and other prominent people within Government circles and amongst Massachusetts high society. Thus, on 29 October, the Court of Oyer and Terminer was dismissed.

In January 1693, a new Superior Court of Judicature was established to deal with the cases of those remaining in prison awaiting trial. The use of spectral evidence was no longer to be permitted.

The new Court was to be presided over as before by William Stoughton who remained as committed to rooting out witchcraft as ever but unable any longer to take spectral evidence into consideration many of the accused had no case to answer and for the first time four accused women, Margaret Jacobs, Rebecca Jacobs, Mary Whittredge, Sarah Buckley, and one man, Job Tookey, were found not guilty.

Even now, Stoughton, who had been so angered by the denial of spectral evidence that he had more than once threatened to resign, did not grasp the sense of public unease. When Sarah Wardwell, Elizabeth Johnson, and Mary Post were found guilty, he personally signed their death warrants. Governor Phips pardoned them. On 21 February 1693, he wrote: When I put an end to the Court there were at least fifty persons in prison in great misery by reason of extreme cold and their poverty, most of them only having spectre evidence against them, and their mittimusses (arrest warrants) being defective. I caused some to be let out upon bail and put the Judges upon consideration of a way to relieve others and prevent them from perishing in prison, upon which some of them were convinced and acknowledged that their former proceedings were too violent and not grounded upon a right foundation. The stop put to the first method of proceedings hath dissipated the black cloud that threatened this province with destruction.

The initial hysteria and lust for blood had begun to ebb as early as the autumn of 1692 when the absurdity of the allegations became apparent. The increasing sense of disquiet was expressed by the Reverend John Hale when he wrote: "It cannot be imagined that in a place of so much knowledge, so many in so small compass of land should abominably leap into the Devil's lap at once."

By May 1693, Governor Phips just wanted the trials ended. As the month wore on the final 23 witches to be tried were acquitted. Those still in prison were pardoned and released upon payment of their legal bills. The Salem Witch Trials had come to an end.

During the hysteria 19 people had been hanged, along with 2 dogs that were suspected of being the Witches familiars, 1 had been pressed to death, and at least 4 had died in prison. In total some 200 people were arrested of whom, 50 were released upon admitting their guilt.

Following the end of the Witch Trials instead of feeling a sense of relief that the Devil's presence had been removed from their community, Salem and the many towns and villages beyond were quickly consumed by guilt, though few at first were willing to admit such.

On 17 December 1696, the General Court in Boston ordered a day of fasting and public penance to take place on 14 January, in regret for the late tragedy at Salem. On the same day the Reverend Samuel Willard read aloud an apology in Boston's South Church to "take the blame and shame of the late Commission of Oyer and Terminer. The twelve trial Jurors also begged forgiveness, though not the presiding Judge William Stoughton, instead he blamed Governor Phips for interfering just as he was about to "clear the land of witches."

In 1702, the Reverend John Hale in his book, A Modest Inquiry into the Nature of Witchcraft, wrote:'

"Such was the darkness of that day, the tortures and lamentations of the afflicted, and the power of former precedents, that we walked in clouds and could not see our way."

It was perhaps the most poignant apology to emerge from that sad time.

The Government, however, did not issue a general amnesty to those who had been convicted and would only hear those cases that had been petitioned for by the relatives of the condemned. On 17 December 1711, the Government in England authorised that monetary compensation be made available for some of the families who had lost land and property because of the trials. It was only now that the Commonwealth of Massachusetts reversed the verdicts on 22 of the 31 condemned. The remaining 9, however, were not to be fully exonerated until 1957.

On 25 August 1706, Anne Putnam Jr, now 26 years old, in her application to become a fully, Covenanted member of the Church, apologised for her behaviour during the Witch Trials. Though she was to choose her words carefully, she was the only one of the girls ever to do so:

"I, then, being in my childhood, should, by such providence of God, be made the instrument for the accusing of several persons of a grievous crime, whereby their lives were taken away from them, whom, now I have just grounds and good reason to believe they were innocent persons; and that it was a great delusion of Satan that deceived me in that sad time, whereby I justly fear I have been instrumental with others, though ignorantly and unwittingly, to bring upon myself and this land the guilt of innocent blood; though, what was said or done by me against any person, I can truly and uprightly say, before God and man, I did it not out of any anger, malice, or ill-will to any person, for I had no such thing against one of them, but what I did was ignorantly, being deluded by Satan."

What fuelled the hysteria that gripped Salem Village and the surrounding countryside is difficult to ascertain. The community was certainly split between competing factions largely centred round the two most powerful families in the village, the Putnam’s, and the Porter's. The Putnam's were Puritan farmers in almost constant dispute with their neighbours over land and had seen their prosperity stagnate as a result of these legal entanglements. The Porters were local entrepreneurs of more liberal outlook whose influence in the village was still growing. The two families had fallen out over a bitter land dispute of 1672 that remained unresolved, now they fought for control of the governing village committee. Indeed, the Reverend Samuel Parris had been the appointment of the Putnam faction on the committee and the Porters were to constantly impede his being paid his salary in full, and it is perhaps no surprise that the accusations of witchcraft began in the Reverend Parris's kitchen.

The Putnam's were eager and enthusiastic accusers. Thomas Putnam Jr signed ten legal complaints and provided evidence against 24 of the accused. His wife, Anne Putnam Sr, an often hysterical and some might say unhinged woman, provided evidence against 48 of the accused witches. Their daughter, Anne Putnam Jr, as we have seen was one of the most virulent and hysterical accusers.

Many of those who had early cast doubt upon the sincerity of the girls claims, like Abigail Hobbs, an assertive and independent woman who was openly scornful of the Puritan social order, and others such as George Jacobs, Dorcas Hoar, Sarah Cloyce, and Susannah Martin, were soon to find themselves accused of witchcraft themselves. Most of them were known to be largely supportive of the Porter's in the village, but an attempt by the Porter's to gather a petition against the initial hearings was stymied by the arrest of 19 of their leading supporters.

The rivalry between the Putnam and Porter families and the fact that most of the accusations were made by people from the poorer eastern end of the village against those from the more prosperous western end, and in the knowledge that following conviction as a witch the condemned persons property became forfeit and was put up for auction, has led many to believe that the Salem Witch Trials provided no more than cover for a massive land grab.

To believe so, however, does not entirely explain the behaviour of the girls who were the fulcrum of events. Why did they behave as they did and sustain it for so long?

Medical explanations for the girl’s collective hysteria has focussed on ergot poisoning caused by a fungus that often infects rye and cereals, a staple diet at the time in Salem. Its symptoms manifest themselves in violent seizures and spasms and make a person appear wild and manic. This theory does not however explain why it affected only these girls and had not been seen or reported upon in Salem before.

Puritan society is in essence deeply misogynistic. Women had little role in society other than to be the obedient helpmates of their husbands and devoted daughters to their fathers. They could hold no official position of power though they could become respected members of the Church and attend committee meetings. These young girls who were expected to remain silent, speak only when spoken to, and carry out their chores without complaint, were suddenly thrust into the limelight. Their initial accusations may have been to cover up their own wrongdoings, but they soon began to enjoy their new celebrity status. They were doted upon, they were excused work, they were listened to, and for a short time at least they wielded unprecedented power.

Following the conclusion of the Witch Trials the Reverend Samuel Parris was to remain in Salem Village for just four years. He had always been a divisive figure, now he was widely blamed as the man responsible for the death of so many innocent people. As a result, few any longer welcomed his visits or listened to his words. When his Church brought charges against him for blasphemy and financial irregularity he left and took up a Ministry in the nearby town of Stow. He died on 27 February 1720.

In 1699, Anne Putnam Junior's parents both died within two weeks of one another and she was left to raise her 9 orphaned siblings on her own. She was destined never to marry and died in 1716, aged just 37.

Abigail Williams, who along with Anne Putnam Junior, had been one of the most vocal and fraught accusers, fearing that she would be punished as the Witch Trials drew to a close, fled Salem Village. She was never seen again.

Betty Parris, the 9-year-old girl who had started it all when she claimed to have been made ill by witchcraft, never again spoke of the events that had so traumatised her community. She died on 21 March 1760, aged 78.

The slave Tituba who had been imprisoned but was never tried or convicted of witchcraft was later released. She was then sold back into slavery to pay for her legal fees. It is not known what became of her.

William Stoughton continued to show no remorse for his role in the Salem Witch Trials. He issued no apology and refused to participate in the many fast days that were called in Salem and elsewhere to seek forgiveness from God for their sins.

He later became Deputy-Governor of Massachusetts, dying on 26 May 1699, aged 70.

Tagged as: Tudor & Stuart

Share this post: