Siege of Mafeking

Posted on 29th July 2021

On 11 October 1899, the Boer Republics of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State had the temerity to declare war on the British Empire. It was the outcome of a dispute that had been simmering for many years.

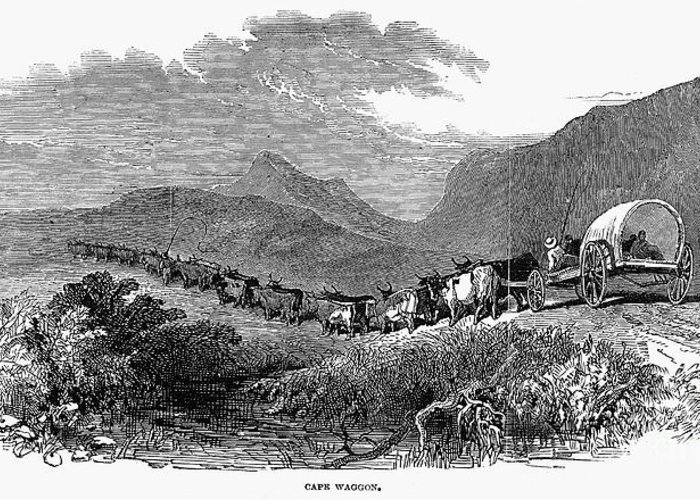

The Boers, descendants of Dutch settlers who had arrived in Southern Africa in the seventeenth century and would later farm the land of British ruled Natal and Cape Colony were a determinedly single-minded and independent people who would seek autonomy in all things including language and religion. They only reluctantly obeyed the strictures of their British masters and when they determined to enforce the abolition of slavery in the colonies it caused the first great rupture in relations.

On 1 December 1834, they elected to move further into the interior and the ‘Great Trek’ as it was to become known was to see thousands of Boers in great waves leave those areas under British jurisdiction to make a country of their own and numerous territories were initially formed which had by the early 1850’s merged into the Transvaal and the Orange Free State.

The British as relieved to see the recalcitrant and truculent Boers go as the latter were pleased to leave had by 1854 recognised both States. This mutual parting of the ways wasn’t always amicable however, particularly when diamonds were discovered in the disputed region of Kimberley in 1866 the rights to which would eventually be ceded to Britain.

Twenty years later gold was discovered in the Witwatersrand region of the Transvaal and people from around the world, particularly Britain and its colonies, flocked to the Boer Republic to seek their fortunes.

The Government of the Transvaal requiring both the investment and their expertise accepted this influx of foreigners but with misgivings. There was a genuine fear that these ‘Uitlanders’ would soon outnumber the Boers in their own land and that they could effectively end up ceding their sovereignty to the British Empire by proxy as a result they were permitted to work but denied all political and civil rights.

Their fears were not without justification, the British were indeed jealously eyeing up the great natural resources of the Transvaal and by denying the Uitlanders the right to vote the Boers had provided the British not only with a justifiable complaint but also with a reason to intervene.

Their worst fears were realised when on 29 December 1895, Leander Starr Jameson, an acolyte of Cecil Rhodes the diamond merchant and since 1890 Prime Minister of Cape Colony, crossed into the Transvaal at the head of 600 Matabeleland Policemen and armed volunteers with the intention of making for Johannesburg and inciting an Uitlander insurrection; but the raid was a fiasco from the outset, not only had the Boers been forewarned and able to mobilise their Commando, but Jameson had neglected to cut the telegraph wires and provided with out-of-date maps soon found himself lost. On 2 January 1896, having wandered around aimlessly for a few days they were surrounded and forced to surrender.

Waiting for news in Kimberley, Rhodes who had planned and financed the raid with the tacit approval of the Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain in London was devastated to learn that his plan to make the whole of Southern Africa a province of the British Empire had been thwarted.

Although the Boers were relieved to discover that there was no desire on the part of the Uitlanders for insurrection and Joseph Chamberlain was very quick to wash his hands of the entire affair the first steps on the path to war had been firmly trod.

Following the failure of the Jameson Raid the issue of the Uitlanders did not go away and negotiations between Lord Milner, the British High Commissioner for South Africa, and the Presidents of the Boer Republics Paul Kruger and Martinus Steyn, were to continue but with little sincerity on either side.

In June 1899, the pretence of negotiations broke down entirely and Chamberlain demanded voting rights for the Uitlanders with immediate effect. But on this issue Kruger would not budge as both Chamberlain and Milner knew he wouldn’t.

To impede the build-up for war and pre-empt any hostile British action on 8 October, Kruger issued an ultimatum that all British forces withdraw from the borders of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State within 48 hours. When they refused to do so on 11 October, he declared war.

To the Imperialists in London and Cecil Rhodes in Kimberley it seemed that all their dreams had come true at once – 30,000 Boer farmers had just declared war on the mighty British Empire. But the British, so eager for war had done little to prepare for it neither had they learned the lesson of a previous short war with the Boers that had ended in ignominious defeat. But still they held to the belief that it would be little more than another colonial police action.

Boer strategy was simple – swift action to eliminate the British military presence in South Africa before it could be reinforced thereby presenting the British Government with a fait-accompli. If they still refused to accept the reality on the ground, then enough time should have been bought to allow the other Great Powers to intervene and force the British back to the negotiating table.

On 12 October, Boer forces invaded Natal and Cape Colony which didn’t at first go as planned but early British victories went unexploited and when Sir George White in command of the largest British field force of 12,000 cavalry inexplicably withdrew to the town of Ladysmith, he had effectively ceded control to the Boers. Ladysmith was soon invested and placed under siege as was the town of Kimberley with its great prize, the arch-Imperialist Cecil Rhodes himself.

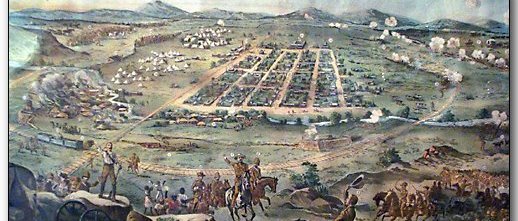

The Boers now moved on to their next target, the strategically important railway junction at Mafeking.

Mafeking was a dusty little town with a population of around 12,000 some 7,000 of whom were black Africans residing in the Baralong district. Also resident in Mafeking were journalists from four London papers – The Times, Morning Post, Pall Mall Gazette, and Daily Chronicle and it was to be their dispatches slipped through the Boer lines by native runners to a British controlled telegraph office 50 miles away that would thrill the British public imagination and make a national hero of its Commanding Officer.

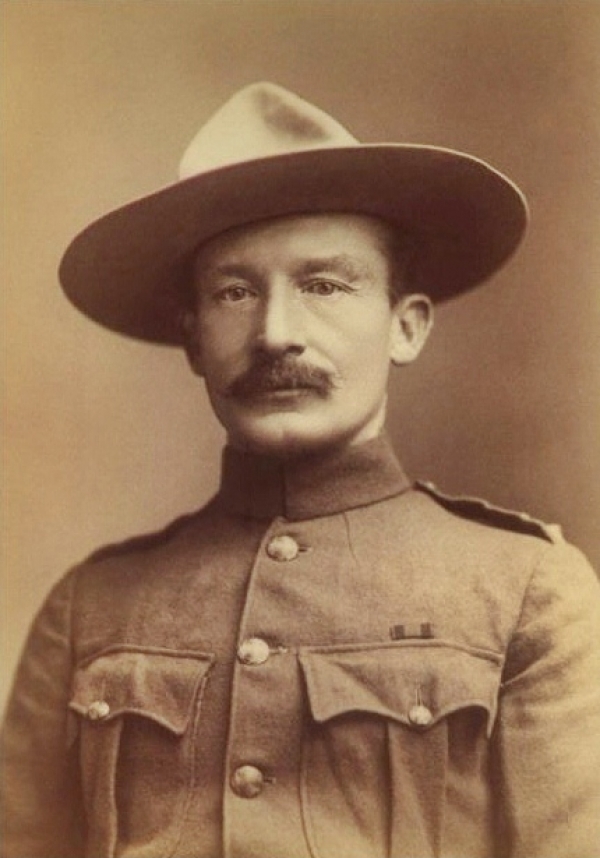

Colonel Robert Baden-Powell was a professional soldier who had spent most of his career in the colonies but had also served for a time with British Military Intelligence were sent to survey military fortifications in the Ottoman Empire he posed as a butterfly collector to sketch detailed maps of gun emplacements and the terrain surrounding them disguised as they were within larger pictures of insects and local fauna.

It was typical Baden-Powell, an eccentric character far removed from the traditional image of the British Officer he was in essence a frontiersman made in the same mould as those who had opened the American West, never happier than when on his own, living off the land, surviving on his wits and making do and mend. He never doubted his ability to get by or to make the most of a bad job.

Since the mid-1880’s he had served in Africa where he fought in the Second Matabele War during which he continued his scouting and reconnaissance duties before being promoted to Colonel following his participation in the Fourth Ashanti War.

When hostilities with the Boers seemed inevitable Baden-Powell was ordered by the British Commander-in-Chief in London Sir Garnet Wolseley to recruit a mobile force to patrol the border with Transvaal and harass the Boer forces, but they moved with such rapidity that he was forced to concentrate on the defence of Mafeking instead.

Baden-Powell’s army was small and unimpressive – 300 part-time soldiers of the Bechuanaland Rifles, a handful of Cape Policemen and 200 militia recruited from the town itself. Aware that as many as 8,000 Boers with artillery under the command of Piet Cronje were advancing on Mafeking, Baden-Powell hastily set about reinforcing its defences.

He immediately recruited a group of young boys to act as lookouts and couriers and armed 300 black men to serve as sentries even though there was in place a tacit agreement, to be broken many times by both sides, that any future conflict would be kept a white man’s war.

Learning of Baden-Powell’s arming of black troops Cronje sent him a harshly worded letter: “You have committed an enormous act of wickedness – reconsider the matter even if it costs you the loss of Mafeking. Disarm your blacks and thereby act the part of a white man in a white man’s war.” He received no response.

Baden-Powell revelled in the art of deception and would often entertain guests with his own magic act, now he would perform similar in his defence of Mafeking.

With the Boers looking on he sent men to plant mines in the approaches to the town, except they had no mines. Instead, he had them bury metal boxes with a brick inside occasionally igniting a stick of dynamite to make it appear that one had exploded accidentally; similarly, he had barbed wire laid, though he had none of that either but knowing that from where the Boers were positioned any barbed wire would appear invisible, he had his men pretend to step over it and even to feign becoming caught up in it.

He had a searchlight made from an acetylene lamp and an old biscuit tin which he had placed on a cart with wheels which he would have wheeled the entire length of the trench-works to make it appear that any part of the town’s fortifications could come under the gaze of searchlights at any time were it to be attacked.

From old and discarded rolling stock in the railway yards he built an armoured train which in an act of great audacity he was to man with sharpshooters and drive right into the middle of the Boer camp causing a number of casualties and great panic before returning it safely to town. This would be typical of Baden-Powell’s defence of Mafeking – he would not simply hang on with a grim determination but would take the fight to the Boers when and where he could.

By the 13 October, having earlier rejected Cronje’s demand that he surrender Mafeking was not only under siege but under bombardment.

The Boers were in no rush to storm the town believing that it would either succumb to the bombardment by their ‘Long Toms’ or be starved into surrender and so in early December Cronje departed with many of his men for more active zones of conflict leaving his deputy J.P Snyman in command.

Cronje’s departure did not reduce the Boer forces significantly enough for Baden-Powell to contemplate breaking the siege and so both sides settled down to a prolonged period of bombardment, sniper fire, raid and counter raid.

Baden-Powell was beset with problems however, though you would not necessarily have known it.

He could not return Boer artillery fire, so he had a howitzer built and adapted an old 18th century cannon for use in the field. He had to secure a regular supply of clean drinking water and he was concerned with the deprivation of food stocks. He also had to combat the perennial shadow of fatigue and defeatism and worked tirelessly to keep up morale. He put on regular theatrical shows and as a fine actor and mimic with himself as the star turn.

He also issued a postage stamp with his image on it and even designed his own currency for use during the siege while every Sunday without fail there would be a cricket match. Indeed, after the wicketkeeper was decapitated at the crease by a shell, he wrote to Snyman suggesting that a truce should prevail on a Sunday. The deeply religious Snyman agreed, though he objected to the British frolicking on the Lord’s Day. Neither did Snyman share or appreciate Baden-Powell’s sense of humour in particular the relentless stream of better luck next time letters littered with cricket and sporting references such as being bowled a googly or hit for six.

He would eventually yield a little and even suggest they play a game to which Baden-Powell replied that he still had to finish his current innings.

For all Baden-Powell’s well-publicised antics however, the siege remained a serious and stark affair and it would be the black population that would bear the brunt of the hardship.

Baden-Powell had early on requisitioned all the town’s food stocks including the grain from the black district and implemented a programme of rationing the burden of which again fell on the blacks reduced to a pint of horse soup sold to them at 3d a day. Although there is little evidence to suggest that Baden-Powell deliberately sought to starve the black population there is little doubt that those not in service he considered to be ‘useless mouths’ not worth feeding and he encouraged them to leave and those unwilling he was not shy in trying to force to do so. The 750 who did so faced the bleak prospect of trying to pass through Boer lines before then embarking on a 100 mile trek on foot to safety. If caught by the Boers they could expect to be stripped and whipped before being forced to return when it was not unknown for them to be fired upon by the town’s defenders.

Such treatment seems particularly harsh in light of the black contribution to the towns defence for not only did they man the trenches, but it was often female black couriers who smuggled out the reporters dispatches at great risk to themselves. Baden-Powell’s would later omit the black contribution to Mafeking’s defence in his official report on the siege.

None of this would have been of concern to a British public thrilled by BP’s exploits and anxiously awaiting the latest reports from the front – was BP still at the crease? Was he still playing a straight bat? It was Boy’s Own Stuff, the novels of G.P Henty made real, and they loved him for it.

After all, the early months of the war had been a disaster for the British militarily and for their reputation as a Great Power. Her army was being beaten in the field, vast swathes of territory had been ceded while many towns still in her possession had been locked down and were under siege. It seemed to many abroad that the greatest Empire the world had ever seen was being defeated by a bunch of Boer farmers. She might even be forced to come to terms. And things were about to get much worse.

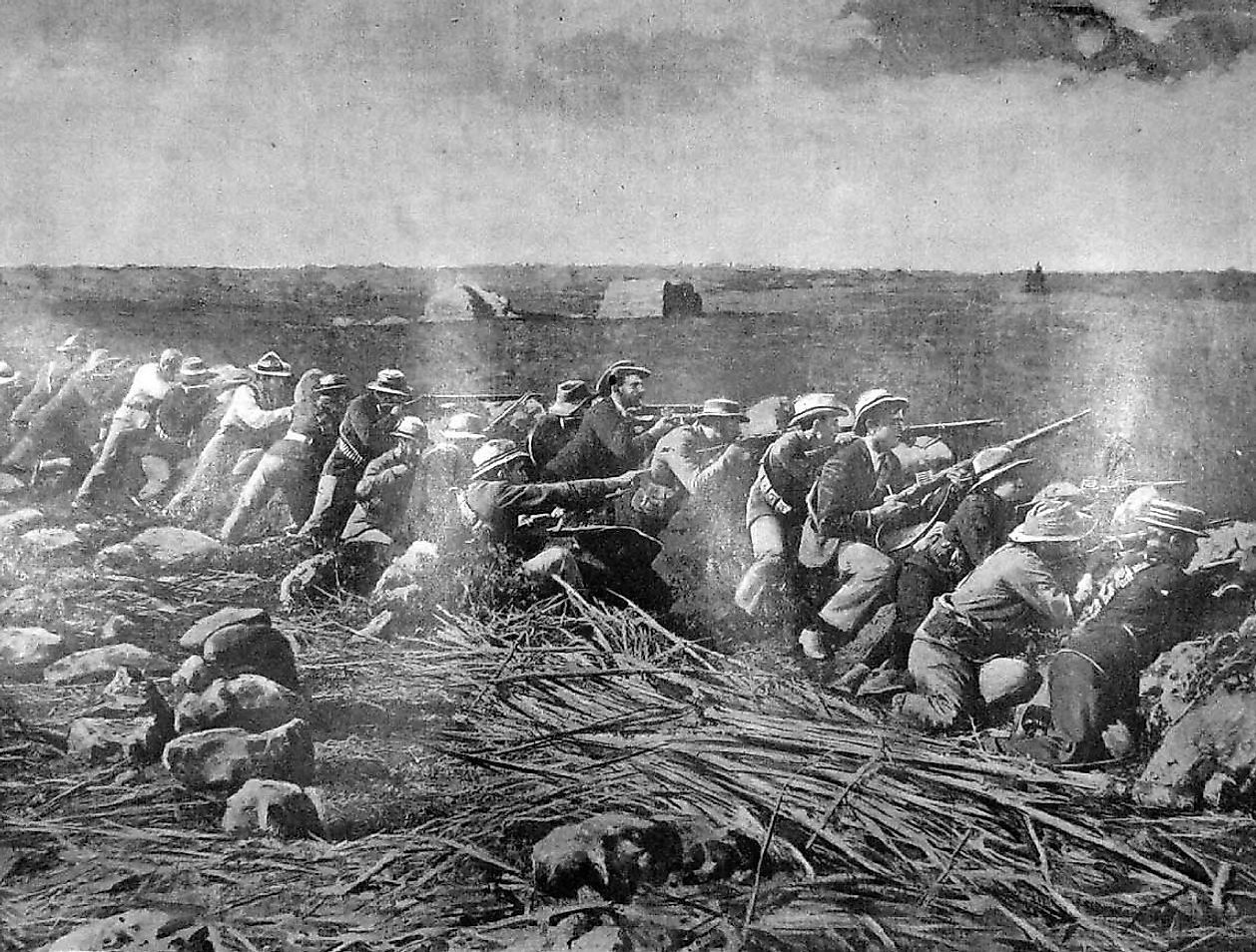

On 10 December at Stormberg Junction having blundered into an ambush 630 British soldiers were forced to surrender having barely fired a shot in their own defence; the following day at Magersfontein advancing over open ground the British suffered 810 casualties for no result before being forced to withdraw; and on 15 December at Colenso, they endured yet another setback when they lost 1,645 men again for no gain. Moreover, the graphic and horrific images of the killing ground that was Spion Kop were to appear in the British newspapers a few days later.

What was to become known as ‘Black Week’ had made Britain the laughingstock of the world and was to see the British Commander in South Africa Sir Redvers Buller renamed ‘Sir Reverse’ and replaced by Lord Roberts.

The trauma of ‘Black Week’ was not only to represent the high watermark of Boer success but it ruled out any prospect of compromise. The war would continue until regardless of setbacks the Empire emerged victorious, but it was only Baden-Powell’s exploits at Mafeking that provided any light at the end of what seemed a very long tunnel and it was to become a British obsession.

The siege soon settled into a routine that despite the shortages and the occasional intervention that led to sudden death was not too dissimilar to the one they were used to.

The Boer ‘Long Toms’ continued to bombard the town reaping their grim toll but they no longer kept people off the streets, neither did the fear of sniper fire or the threat of a sudden Boer attack.

On 26 December, Baden-Powell launched an assault on the Boer strong point at Game Tree Fort. It was to prove a costly failure, but he was not downhearted – well bowled! He would say. But then he would make such attacks not because he believed they would break the siege but rather that it was unhealthy for his men to remain idle.

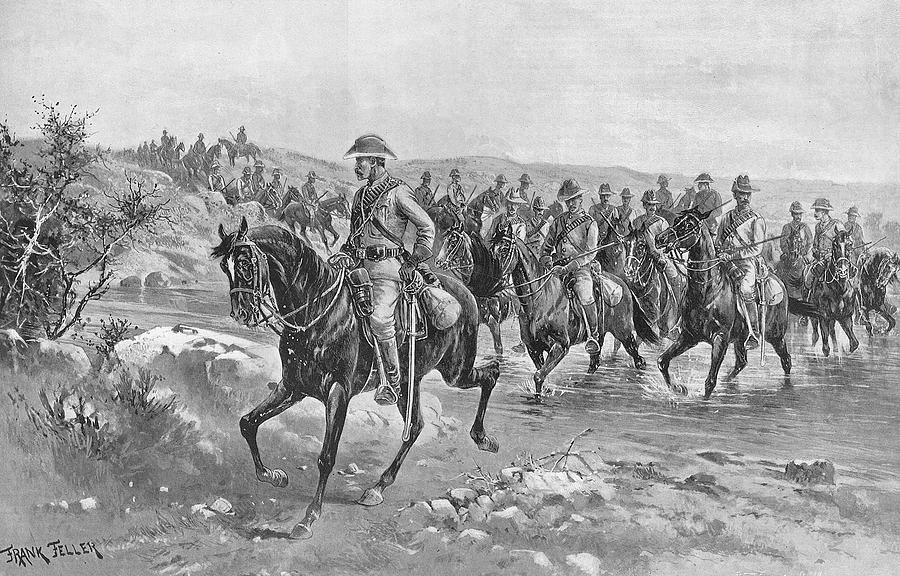

On 15 February 1900, the town of Kimberley was relieved to be followed on the 28th by Ladysmith and it was believed that Mafeking would be next, but it didn’t happen quite as soon as some perhaps expected.

Even so, rumours that a Flying Column of 1,200 cavalry under the command of Colonel D.T Mahon was closing in on Mafeking forced the Boers to act. Sarel Eloff, a confident young man and a grandson of President Kruger believed Mafeking could be taken by infiltrating it at night thereby causing panic and distracting the defenders sufficiently enough for an offensive by Snyder and the bulk of the Boer army to succeed. He even boasted that he would be dining in the Dixon Hotel by lunchtime.

Just before dawn on 12 May, Eloff with 250 men slipped between two forts and into the black part of town where he set light to several huts as the signal for Snyder to begin his attack. But Snyder did not attack.

Even so, Eloff enthused at his own success, including the taking of 30 prisoners among them Baden-Powell’s second-in-command, now phoned him to boast of it. But Baden-Powell had already been made aware of events by the burning of the huts and had been quick to respond. He reinforced those troops barring Eloff’s further advance in the knowledge that more than 100 armed blacks who had laid low during the attack on the township were now also barring his retreat.

Aware that no general Boer attack was taking place and fearing that they were advancing into a trap many of Eloff’s men expressed the view that they should either retreat or surrender. Under the threat that anyone who did so would be shot many simply disappeared.

In the end he was forced to retreat with the men that remained to him to a police barracks where he was quickly surrounded. He resisted only for a short time and Eloff was to indeed dine at the Dixon Hotel that afternoon but as a prisoner and guest of Baden-Powell.

With the Flying Column closing in Snyder withdrew the Boer forces from around Mafeking.

On 16 May, as British cavalry rode down the main street of Mafeking, Baden-Powell queried what had taken them so long.

For all Baden-Powell’s theatricality and eccentric behaviour, the Siege of Mafeking had been every bit as grim as that of either Kimberley or Ladysmith. The town had come close to starvation, Baden-Powell’s rule had often been oppressive and harsh, and the constant bombardment had reaped a predictably grim harvest.

The siege had lasted 217 days during which the defenders suffered 812 casualties of whom 212 were killed. There are no accurate figures for the number of black victims. The Boers had endured around 1,000 casualties including perhaps 400 killed mostly in early attempts to storm the defences.

The Boer decision to besiege Kimberley, Ladysmith and Mafeking had been a strategic error tying up a substantial number of troops and ordnance when with the British army at bay they could have been used more effectively elsewhere.

Also, the Boers, fine marksmen and horsemen were not trained to fight set-piece battles and their failure to truly understand the rudiments of siege warfare was to be their undoing.

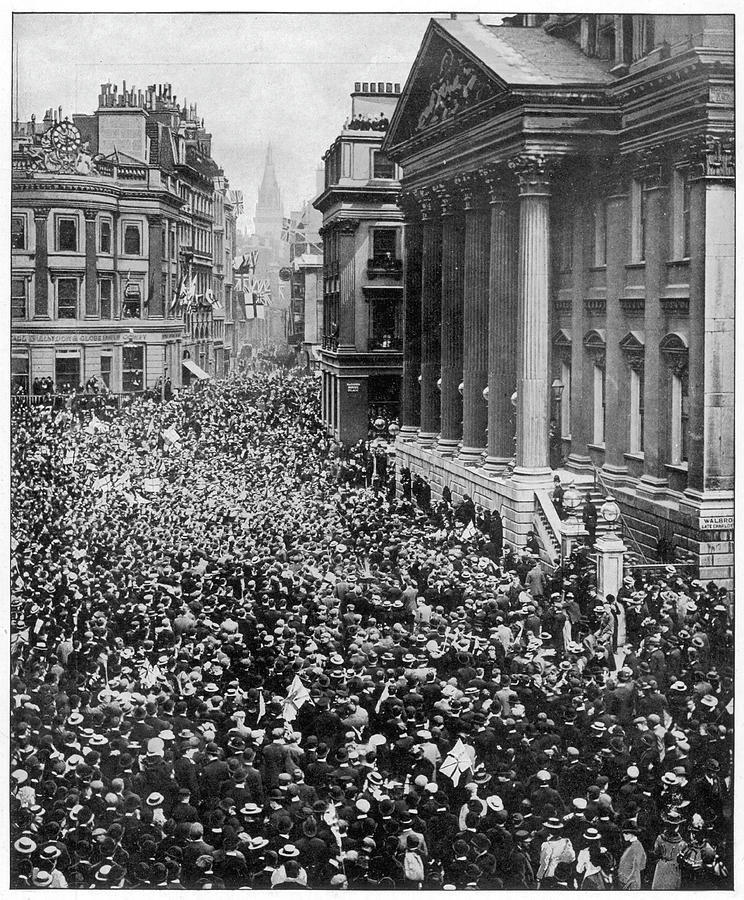

News of the Relief of Mafeking made headlines around the world and in Britain it was greeted with scenes of wild jubilation rarely seen before and way beyond its military significance as millions of people spilled onto the streets of towns and cities the length and breadth of the country in celebration.

In London as flag-waving crowds thronged the city centre theatres and concert halls interrupted their performances to announce the news – Mafeking Relieved! BP safe!

As workers downed tools, the city ground to a halt, the pubs began to run out of beer and the celebrations continued late into the night the Government fearing that the raucous crowds might get out of hand considered reading the Riot Act.

Baden-Powell was to return to Britain a national hero and promoted to the rank of Major-General in October 1901 he was received by the King at Balmoral. The greatest hero since the Duke of Wellington his image was seen everywhere as his fame was marketed to the hilt – there was BP Jam, BP Mugs, BP Sheet Music, BP Clothing, even BP Cigars, something he would have hated – he was the most famous man in the Empire.

Unlike many who become the subject of such public adulation Robert-Baden Powell was to find even greater fame in later life when he used his love of the outdoors, his knowledge of field craft and reconnaissance, and his sense of duty and responsibility borne of his deep Christian faith to form the Boy Scout and Girl Guide Movements for which, along with his great triumph at Mafeking, he would later be knighted.

Share this post: