Sir Thomas More: A Martyr to Conscience

Posted on 15th May 2021

To the Catholic Church he is a Saint while in the country of his birth he is thought of as a liberal reformer but in truth he was neither and remains one of the most misunderstood and misrepresented figures in English history.

A Renaissance Humanist he was also a ruthless politician and religious zealot who though he was to die a martyr to freedom of conscience it was his conscience alone and no one else’s. In the end he feared his faith more than he did the King and God more than he did death.

He was born on 7 February 1478 in London, the son of a lawyer and he was to follow in his father's footsteps studying law at Oxford University and despite his father falling out with King Henry VII the family remained well-connected with Thomas often staying with John Morton the then Archbishop of Canterbury, from whom he received an early and intense religious grounding.

Once qualified as a lawyer his rise through the profession was swift and impressive and he early earned a reputation for honesty at a time when corruption and political graft were commonplace imparting justice speedily and fairly. It was clear Thomas More was not a man who could be bought.

In 1510 at the age of just 32 he was appointed as one of two under-Sheriffs for London and by 1517 had come to the attention of the Royal Court where he was soon employed in the service of the recently crowned King Henry VIII.

The young King tall, broad shouldered and athletic with a mane of red hair and a complexion both pale and glowing impressed all who met him. He was both a vigorous and energetic man who turned heads on the tennis court, was eager for the joust and enjoyed the hunt whether that be for game or women. But he was also well read, an accomplished musician and a committed Catholic. He yearned not just to be a Warrior King in the mould of Henry V, but a Renaissance Prince admired throughout Europe for scholarly as well as manly pursuits.

The learned and persuasive Thomas More was to be the perfect foil for his ambitions, and he was always more than just a trusted advisor to the young Henry he was both a confidante and a friend. They were on first name terms and regularly exchanged gifts.

With the King for a friend Thomas More's career flourished; in 1521 he was knighted, in 1523 he became Speaker of the House of Commons and two years later was appointed Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. It was also around this time he made the acquaintance of the greatest Humanist thinker of the age, Erasmus of Rotterdam, and established a reputation as a scholar with his History of Richard III, that quintessential piece of Tudor propaganda which established the Tudor Dynasty in the eyes of its European rivals.

Earlier in 1516 he had written his seminal work Utopia in which he envisaged a perfect society, one that was governed by reason and prayer where difference was to be tolerated and everyone lived in perfect harmony.

More believed in the rule of law and in a strict social hierarchy and underpinning this hierarchy was the Catholic faith and the Unity of Christendom. As far as he was concerned, this was God's Grand Design for the World.

The Unity of Christendom was essential for the harmony of the world, and it could only be this that guaranteed its laws and ensured the salvation of souls. Atheists and Heretics imperilled this order and the greatest threat posed came from Lutheran Reformers. Their denial of Church authority and of the need for a priest to intercede on the path to salvation was heresy of the highest order.

The idea of a literal interpretation of the Bible and of its availability to all in their own language endangered everything he believed to be true, and he would oppose it with all the power at his disposal.

In his role as a diplomat in the service of the Chancellor Cardinal Wolsey that More, attended the overdressed extravaganza of amity between England and France that was the Field of the Cloth of Gold in June 1518.

It was here that Henry VIII met Anne Boleyn for the first time, and little could More have known that subsequent events would precipitate not only his own downfall twelve years later but that of the Catholic Church in England.

Anne Boleyn was just seventeen years of age at the time of the Field of the Cloth of Gold and serving as a lady-in-waiting to Queen Chlode of France. She was described as 5'3" with a delicate frame, slender neck, pale skin, brown hair, and large dark eyes she was by no means conventionally beautiful but with a teasing intelligence and flirtatious manner she understood the art of love and how to attract men.

Anne had many admirers but Henry at the time was not among them, his head had instead been turned by her more attractive sister Mary, whom he made his official concubine. However, when he was introduced to Anne for the second time in 1525, he very quickly became besotted with her but unlike her sister when he offered her the opportunity to become his mistress she refused.

Anne was aware that her sister had become a laughingstock often referred to as the King's Whore and she wanted more than simply being seen as the national prostitute. She was ambitious, and she was to be ruthless in pursuit of her ambitions. She demanded respect, she wanted to be Queen, and Henry melted in a puddle of adoration.

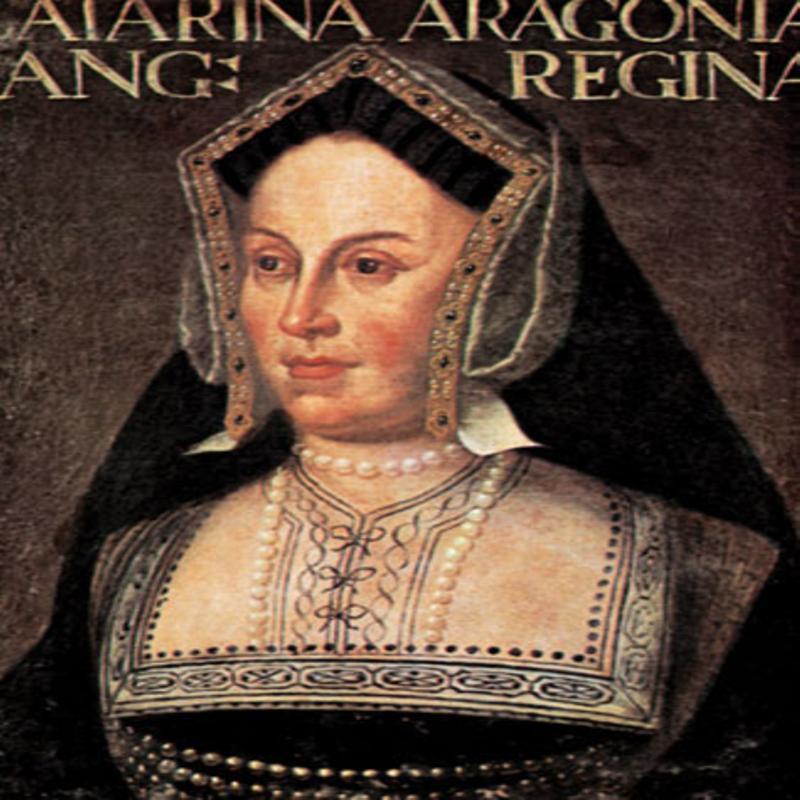

The King however was already married to Catherine of Aragon, the daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, and the aunt of Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor. She had previously been married to Henry's older brother Arthur but when he died a special dispensation, based on the non-consummation of the marriage had been sought from the Pope to permit her to wed Henry.

The marriage was considered important because the Tudor dynasty had scant legitimacy and a union with the most powerful family in Europe would acquire for them the dynastic respectability they craved. Alas Catherine had failed to provide Henry with a male heir. She had given birth to a healthy daughter it was true, but England had never before been ruled by a woman. By not providing Henry with a son, she had failed in her duty as Queen.

Catherine of Aragon was a hard-working, intensely formal, deeply religious and earnest woman the very opposite to the lively fun-loving Anne. Henry bored with his wife wanted rid of her, but this was easier said than done. He had also convinced himself that the reason Catherine was barren at least with respect to producing a male heir was because by marrying his dead brother's wife he had committed an unclean act, and he sought and found Biblical justification for this belief.

Despite his best efforts Catherine resolutely refused to grant him a divorce so in response an increasingly frustrated Henry approached Pope Clement VII directly for the marriage to be dissolved on the grounds that Catherine had earlier consummated her marriage to his brother Arthur. Alas for Henry, Rome had recently been sacked by the forces of Charles V, Catherine's nephew and the Pope was effectively a captive. He could not now grant Henry his divorce even if he had wished to do so.

Furious that he could not even divorce his own wife Henry now placed the affair in the hands of his Chancellor Thomas Wolsey. He had never previously failed Henry and would surely bring his expertise to bear in resolving the “King's Great Matter”.

Cardinal Wolsey arranged for an Ecclesiastical Court to meet in London under the auspices of the Pope's Representative Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio who after reviewing the evidence would make the final decision. The Court met throughout 1528 and heard many witnesses but it was Catherine herself who would dominate proceedings.

Testifying that she was still Virgo Intacta at the time of her marriage to Henry, she prostrated herself at the feet of the King and in floods of tears extolled her chastity, denied all accusations of consummation, declared her undying love for His Majesty and begged his forgiveness if she had offended him in any way. Having said all that, she wished to say she rose to her feet and with her head held high and looking straight ahead walked slowly from the Court refusing all demands to return. She was the wronged woman, and she wanted the world to know it. Her popularity with the people soared and as a result Anne Boleyn became the "Goggle-Eyed Whore."

In the furore that followed Cardinal Campeggio dissolved the Court and ordered that Henry must not re-marry until a decision had been made in Rome. Henry was furious and he blamed Cardinal Wolsey but even, so he was reluctant to move against a man who had done him such loyal service over so many years. But accusations made against him by both Anne and her family were to result in his removal and he was later to face charges of High Treason.

Wolsey died in early 1530 of natural causes having saved him from the ignominy of the executioner’s axe.

In his search for a replacement for the "Butchers Son" as Wolsey was so often derided, Henry did not have to look far. Who was better qualified to be Chancellor than the finest mind in Tudor England and who could be more trusted to do his bidding than his old friend, Sir Thomas More. But it was a poisoned chalice and Sir Thomas knew it. Twice he declined the appointment until the King's wrath, and a Henrican rage could be something to behold, induced him to do so.

Sir Thomas was believed to be opposed to the divorce and it was thought by many that Henry had placed too much trust in his old friend. In fact, Sir Thomas and Henry had spoken at great length about it and it was agreed that as Chancellor Sir Thomas would remain silent on the issue of the divorce and Henry in turn would not vex him on the matter.

Free of the King's Great Matter, so he thought, Sir Thomas More was now able to use the powers of his new office for the thing that mattered most to him, the rooting out of heresy in England. He had previously been committed to the interception and burning of Lutheran literature, now he would burn the Lutheran's responsible for its importation and distribution. He personally oversaw the interrogation of suspects and endorsed the use of torture to force confessions.

This was something that he denied doing at the time, but he could not likewise deny that he condemned people to be burned at the stake, executions over which he would preside in the hope of obtaining a last minute recantation. Indeed, such was his ruthlessness in pursuit of heretics that it even unsettled the King.

As Sir Thomas busied himself burning heretics, the King's Great Matter continued to loom large. Thomas Cromwell, the King's ambitious Private Secretary and the Cambridge theologian Thomas Cranmer would drive the King's divorce through Parliament and over the opposition of the clergy. But they also had an agenda of their own - to bring down the Catholic Church in England.

If Sir Thomas truly believed that he could ignore the King's Great Matter, then he was either very naive or foolish in the extreme. In this matter he should have taken his own advice: "I never met a fool yet who thought himself other than wise".

He had let it be known publicly that he did not oppose the divorce and Henry's marriage to Anne Boleyn, but few believed him. He had long been an outspoken advocate of Queen Catherine, not as outspoken perhaps as John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, but they were good friends and known to share similar views.

In 1531 Henry VIII formally broke with Rome and declared himself Head of the newly created Church of England and he was now able to grant himself the divorce. In recognition of this fact, he demanded that an oath be taken accepting the new religious order and acknowledging the progeny of Anne Boleyn in the line of succession. Sir Thomas More felt unable to take this oath. He could not accept the break with Rome and the subsequent disunity of Christendom, but he promised that he would continue to remain silent on the issue of the oath and not oppose it, but neither would he support it. His silence was to prove deafening, however.

In late 1532 he resigned the Chancellorship claiming ill-health though few believed this to be the real reason. Only reluctantly did Henry accept his resignation expressing both his disappointment and his best wishes for the future.

Henry appointed Thomas Cromwell as his replacement and the pro-Catherine lobby suffered a further blow when in the spring of 1533 William Warham the Archbishop of Canterbury, and another high-profile opponent of the divorce, died.

Anne Boleyn and her family now persuaded Henry to appoint Thomas Cranmer in his place and they were determined to bring down the one man who remained as a barrier to their ambitions.

Sir Thomas More was a man with a Europe wide reputation as a scholar and a humanist, when he spoke people listened and as an advocate of the old religion, he stood in the way of Protestantism being established in England. As long as it was presumed, he was opposed to Henry's marriage to Anne Boleyn many would not accept its legitimacy. He could not be permitted to remain silent on the issue. He must either take the oath or suffer the consequences for not doing so.

A lawyer by training, Sir Thomas believed that he could take refuge in jurisprudence particularly as it was acknowledged in law that silence denoted consent not opposition.

On 1 July 1533, he failed to attend Henry and Anne Boleyn's Coronation. Although he had informed the King of this in advance and had once again reaffirmed his commitment to remain silent his actions spoke louder than words. It was seen by Henry and across Europe as a deliberate snub.

For his many enemies it was as much his reputation for honesty, propriety and scholarship that he could not be left alone. Thomas Cromwell in particular perceived him as a threat to his Reformation agenda and was determined to be rid of him.

His attempt to secure a charge of treason against Sir Thomas began poorly however, when he accused him of corruption for to do so was patently absurd as everyone knew that if anyone wasn't corrupt it was Sir Thomas More. He then tried to associate him with Elizabeth Barton, The Holy Maid of Kent, who claimed to have had visions and to be in direct communication with God. She had earlier prophesised that should the King marry Anne Boleyn he would die very soon after.

She had been hanged for treason, but it was known that Sir Thomas had visited the Holy Maid on several occasions. Cromwell suggested that he had colluded with her in acts of treason but in his defence Sir Thomas was able to produce a letter that had been witnessed in which he had advised her to stop speaking out against the King.

In April 1533, Sir Thomas was summoned before a Special Tribunal to explain his reasons for not taking the Oath. However, he steadfastly refused to answer any questions maintaining his silence on the issue. On 17 April the following year Thomas Cromwell issued a writ for his arrest on a charge of High Treason, and he was imprisoned along with Bishop Fisher in the Tower of London.

Not long after his incarceration he wrote to his daughter Margaret, known as Meg, of whom he was particularly fond and had taken it upon himself to educate to a very high standard at a time when it was not thought proper to do so: "I do nobody harm, I say none harm, I think no one harm, but wish everyone good, and if this be not enough to keep a man alive, then in good faith, I long not to live".

Despite his best endeavours Cromwell was unable to dissuade More from his chosen path. He would neither take the oath nor speak publicly on the issue. He was not yet resigned to martyrdom, but he was willing to die for the Catholic faith if that was shown to be God's Will.

Sir Thomas More was brought to trial on 1 July 1535. On the Panel judging him were Anne Boleyn's father, brother and uncle, implacable enemies one and all. The verdict then was a foregone conclusion despite the fact that he was formally tried before a Jury of his peers.

Questioned yet again on the King's Great Matter he again refused to answer stating that in law his silence must be taken as consent. He was correct in law but in the end was to be convicted on the perjured evidence of the Attorney-General for Wales Sir Richard Rich, who claimed that Sir Thomas had told him the King did not have the authority to declare himself Head of the Church of England and so could not grant himself the divorce.

Once the verdict of guilty had been passed Sir Thomas at last spoke his mind. He denied the legitimacy of the Act of Succession and refuted the Oath of Supremacy saying that: "No temporal man, regardless of who he was, could declare himself the head of spirituality.” He then proceeded to condemn the divorce and declared that if he were still Chancellor then he would pursue his truth every bit as vigorously as Cromwell now pursued his.

Having spoken before the Court as was his right, he was sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered. Henry was both depressed at having to execute his old friend and angry with him for making him do so. It was with reluctance that he signed his Death Warrant but in an act of leniency he commuted the sentence to beheading only.

On 17 July 1535 Sir Thomas More was beheaded on Tower Hill. His last words were: "I die the King's good servant, but God's first."

Sir Thomas More died for the sake of a deeply held faith and liberty of conscience but did not die for the rights of those he would have considered heretics. Within a year of his execution Anne Boleyn accused of adultery also went to the scaffold.

Following beatification Sir Thomas More was declared a Saint by the Catholic Church in 1986.

Tagged as: Tudor & Stuart

Share this post: