Slave Ship Zong

Posted on 19th April 2021

In the eighteenth century there was no trade as lucrative as the slave trade with cities in England such as Bristol and Liverpool benefitting greatly from the proceeds of it. Indeed, the country could be said to have prospered as a result of being the commercial centre of the trade in human lives with the Industrial Revolution that followed largely financed by the money made from the sale of slaves. Moreover, with the gathering of cotton in the American South and the cutting of sugar cane in the Plantations of the Caribbean labour-intensive work it appeared a trade with a bright future - there could never be too many slaves.

This is not to single out or denigrate Britain in any way slavery was commonplace the world over in all cultures and societies and very few Englishmen ever owned a slave while they were never used in the country to work down the mines or toil long hours in the fields and factories. In that respect Britain has never been a slave owning society; but it was increasingly, Utilitarian and business was business with few people questioning the morality of the slave trade. Indeed, some even viewed it as a moral good with the paternal aspects of slavery seen as necessary to the civilising of the savage races.

Even so, the 1780's were to see the first stirrings of an abolitionist movement led by dissenting religious groups such as the Quakers and the Methodists, and it was to be provided with great early impetus by the affair of the Slave Ship Zong.

Most slaves were captured by other ethnic Africans in inter-tribal conflicts. They would then be transported to the coastal ports where they would be traded for goods to Arabs acting as the middlemen in a trade that would see them sold onto European slave traders who would rarely themselves venture beyond the coastal ports fearing the African interior of which they had little knowledge.

Rarely were the slaves purchased ever thought of as being human beings, they were goods bought and sold for profit, nothing more nothing less.

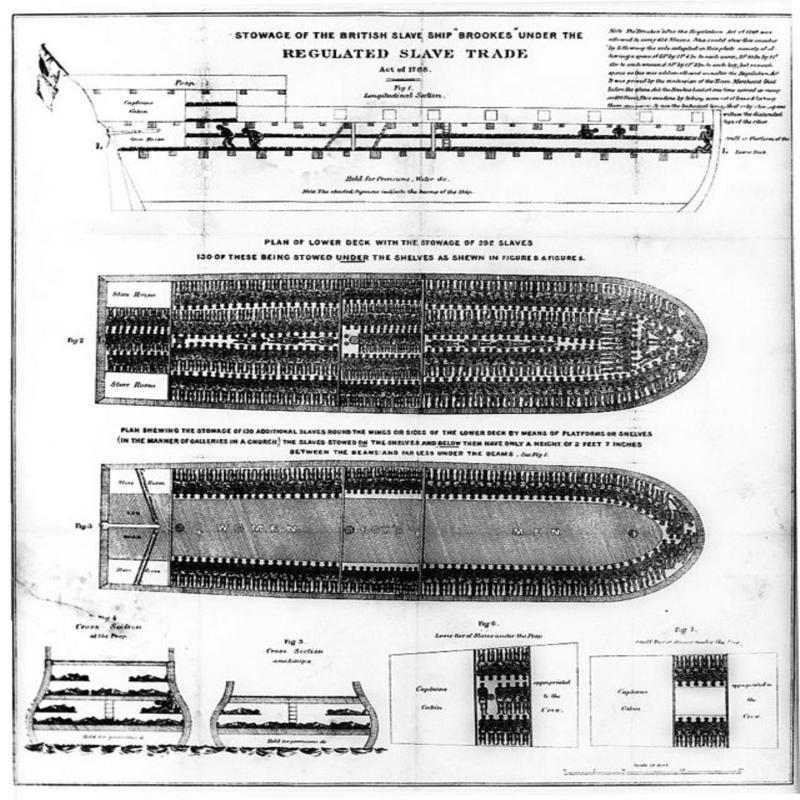

The conditions upon the slave ships were quite simply appalling and the treatment of the slaves inhumane and degrading; they were first stripped naked and examined by the ship's surgeon although they were rarely qualified to do so. It was his job to keep as many of the slaves alive as possible and he would be paid according to how many healthy slaves were later sold at auction. The requirement for healthy slaves did not entail improved treatment or care however, rather it meant the quick elimination of the sick before they could infect the others.

Following examination, the men were shackled and taken below decks where no space was left unused. Chained to their bunks in cramped conditions they were not permitted to stand up or walk about. There was no sanitation and the men urinated and defecated where they lay. The air was foul and putrid, the heat unbearable and sea-sickness manifest.

The women and children were quartered separately, often on deck, but conditions were no better for being exposed to the elements. Both the women and the children were prey to being sexually abused by the crew and rape was commonplace.

The slaves were fed twice a day, force fed if necessary. It was important that their strength be maintained for the forthcoming sale in the slave markets of the Caribbean. Now and again the men would be brought on deck for exercise, and they would often be made to dance for the entertainment of the crew. If they refused they were often beaten before being forced to kneel and thank the perpetrator for their chastisement.

Rebellion among the slaves was greatly feared and as a result no recalcitrance or insubordination would be tolerated with the preferred choice of punishment the lash or branding with hot irons, though the use of either would mark out the recipient as trouble and diminish the price of the product they intended to sell. The other great fear was an outbreak of disease, and dysentery and the flux were common.

The Slave Ship Zong was registered in Liverpool and owned by James Gregson and Company. It had made many trips to Africa and the Caribbean making a great deal of money for its owners and it now had a new Captain Luke Collingwood, who had previously been the ship’s surgeon. It was his first command, so he was by no means an experienced mariner.

When the Zong set sail from Africa on 6 September 1781, it was with a full load.

Collingwood was aware that he and his crew would be paid according to the number of fit, healthy slaves he landed and looking to secure for himself a comfortable retirement he had crammed the ship full of slaves well beyond its capacity, to do this was fairly common practice but it also ran the increased risk of disease in the insanitary conditions.

By 28 November, a combination of ill-winds and inept seamanship found the Zong becalmed in mid-Atlantic. By this time 7 crewmen and 60 black slaves had already died of disease and many others were sick and seemed unlikely to survive the voyage. The following day Collingwood, himself suffering from a fever, gathered the crew on deck to inform them that he intended to throw those sick but still alive slaves overboard. It was legitimate under the terms of the Jettison Clause for the Captain to dispose of cargo overboard if its retention imperilled the safety of the ship. He explained that if a slave was to die on board or soon after landing from natural causes then the cost would have to be borne by each individual crewman and that the Jettison Clause had priced each slave at £30, a great deal of money. But if the sick were jettisoned before reaching port, then the ship’s insurers would have to bear the cost. It was also vital that the sick were discarded before they infected anyone else, and it was bad for business to dock with a diseased ship.

Few of the crew spoke and only the First Mate James Kelsall demurred, and he was overruled.

Later that day 54 slaves, weak from disease and having been denied food (it was considered a waste of resources to sustain the sick) were dragged on deck and released from their shackles, again to save money, and thrown overboard into the freezing ocean to drown. They were followed on 29 November by 42 others, and later by a further 26. Amid the chaos of struggling bodies and the cries of the soon to be murdered a further 10 slaves took their own lives. In total 132 slaves died, and Collingwood was delighted at a problem solved.

Back in Liverpool both he and the ship's owners immediately made a claim on the ship’s insurance. The claim was to be contested, however. It seemed that Collingwood's declaration of events did not seem to ring entirely true. He had claimed that the sick slaves had to be disposed of because of water depreciation. Yet when the surviving slaves were disembarked in Jamaica the Zong was found to be carrying 420 gallons of water. So, in March, 1783, the case went to courtbut by this time the star witness, Captain Collingwood, had himself died.

The details that were to emerge from the Court Case were to shock the nation and for the first-time groups began to be formed in opposition to the continuation of this abominable trade.

Prior to the Affair of the Zong, Granville Sharp had been a rare voice in Georgian England against the slave trade. He had earlier received a visit from the freed slave Olauda Equiano whose autobiography had opened many people's eyes to the cruelties of the slave trade. It was following their meeting that Sharp decided to bring a prosecution against the owners of the Zong for murder.

Sharp’s attempt to bring a private prosecution in the Zong Affair for murder was treated with contempt by the Attorney-General John Lee:

"What is this claim that human people have been thrown overboard. This is a case of chattels and goods. Blacks are goods and properties; it is madness to accuse well-serving honourable people of murder. They acted out of necessity. The case is the same as if wood had been thrown overboard”.

He was not a man to be swayed by public opinion or even the presentation to Parliament of a petition for the abolition of the slave trade by representatives of the Quakers. He formally announced that it was legal for a Master of a ship to drown slaves if he believed it was necessary to do so for the safety of the ship and its crew. Masters, he said, "could drown slaves without any sense of impropriety”. As far as the Court was concerned the death of 132 slaves was an irrelevance, and how they died was not a point of issue.

Neither the deceased Captain Collingwood, the ship's owners, Gregson, or any member of the crew was in the dock accused of murder. The case was merely that of a fraudulent insurance claim. The law stated that: "The insurer takes upon him the risk of the loss, capture, and death of slaves, or any other unavoidable accident to them but natural death”.

Despite the testimony of First Mate Kelsall who was appearing for the insurers and described the whole affair as something of horrid brutality, the Court found in favour of the ship's owners. Despite the Courts judgement being in favour of the slave traders the Zong Affair was to change everything.

In May 1787, the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was formed and over the next few decades the very idea of slavery was to become increasingly unacceptable to the British people. Campaigns by Baptists, Methodists, Quakers, and prominent individuals such as Granville Sharp, Thomas Clarkson, Josiah Wedgwood, and their spokesman in Parliament, William Wilberforce, would eventually force Parliament to act.

On 25 March 1807, the slave trade was made illegal throughout the British Empire though the ownership of slaves was not and it wasn't until 28 August, 1837, that slavery itself was abolished.

This wasn't simply taking the moral high ground it was to be a law enforced with rigour and between 1808 and 1860 the Royal Navy's West African Squadron intercepted and captured more 1,600 slave ships and freed more than 150,000 slaves. Those rulers in regions of Africa under British influence who permitted slavery to flourish were forced to comply with its abolition with those who refused often facing the hangman’s noose as a result.

Tagged as: Georgian

Share this post: