Tay Bridge Disaster

Posted on 15th June 2021

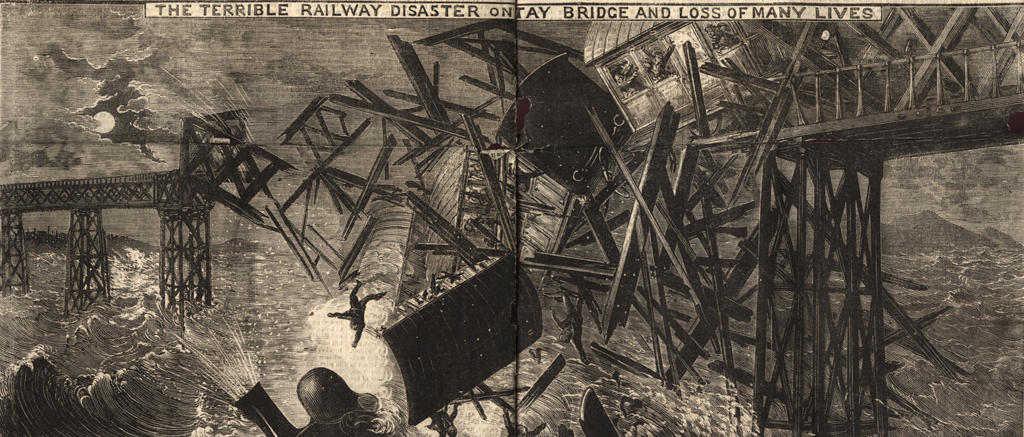

On 28 December 1879, at just before a quarter past seven at night in the midst of the most violent thunderstorm in living memory the Northern Railways Express Train travelling from Edinburgh to Dundee via Wormit was given the all clear to cross the recently built Tay Bridge.

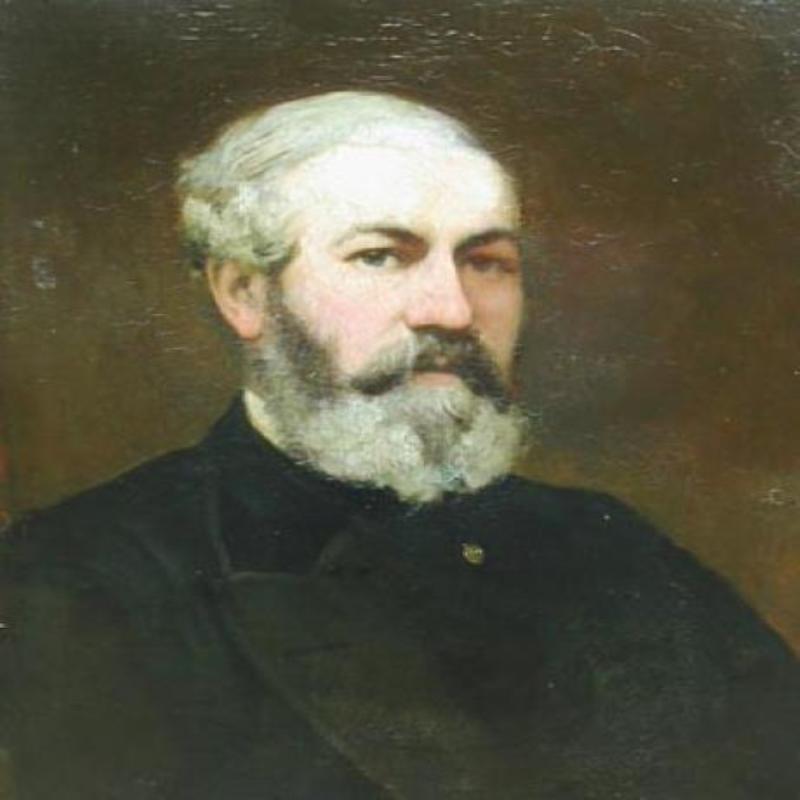

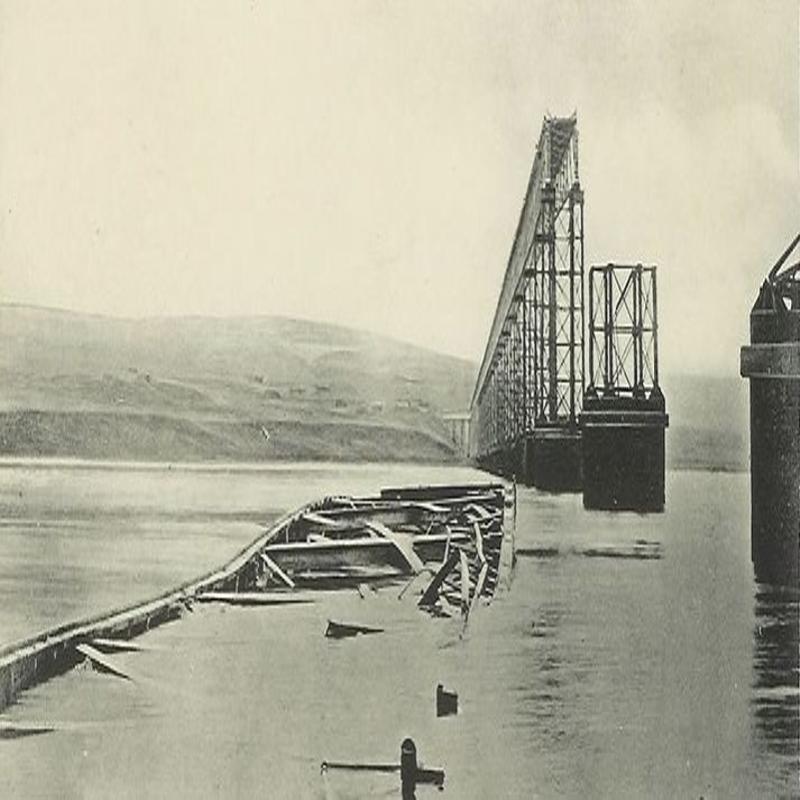

The Tay Bridge at almost two miles in length was the longest railway bridge in the world and was considered yet another great feat of Victorian engineering. It had only been formally opened in February 1878 and had been traversed in June 1879 by Queen Victoria who had been so impressed that later that month she knighted its designer, Thomas Bouch.

Thomas Bouch was an experienced civil engineer who had worked for the various railway companies for more than thirty years and he had been largely credited with designing the first roll on-roll off ferry and had recently presented his designs for a similar bridge across the Forth of Firth. With a reputation as an innovator, he was highly respected by his contemporaries and popular with his employers as a man who worked within budget and saved them money.

The Signalman in his cabin could see the fire in the engine being stoked and the carriages of the train brightly lit as it sped its way across the bridge when suddenly the scene was plunged into darkness. There was evidently a problem with the train, but little could be heard because of the howling wind.

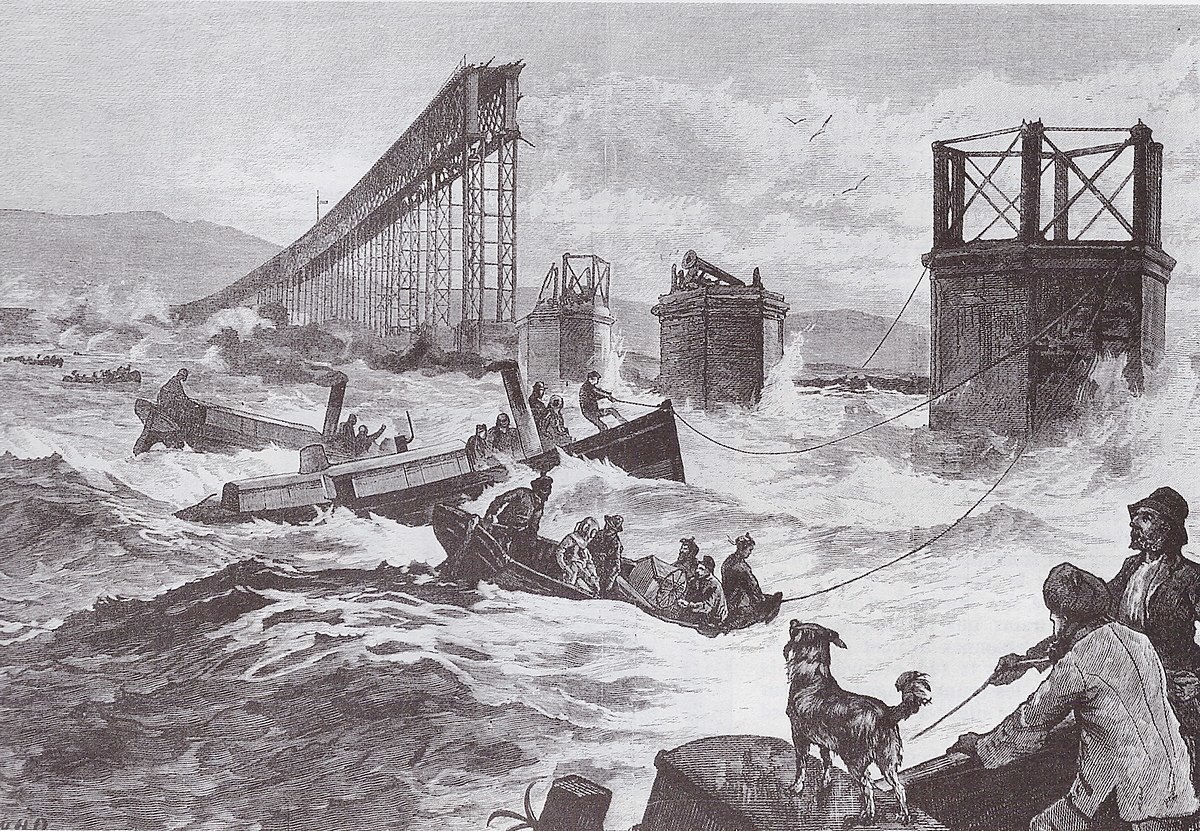

It wasn’t until the following morning and the coming of daylight that it became clear a tragedy had occurred. The entire middle of the bridge had collapsed and upon learning that the train bound for Dundee that night had never reached its destination a search and rescue mission was immediately undertaken but it was too late and there were to be no survivors.

Divers later found the train lying at the bottom of the storm lashed River Tay still between the girders of the collapsed bridge. Some of the passengers were discovered still in its carriages but many had been swept away in the storm and only 46 bodies were recovered of the 75 passengers estimated to have been aboard.

A Court of Inquiry into the disaster was established almost immediately under the stewardship of Henry Cadogan Rothery, the Commissioner of Wrecks who was a man with a reputation for plain speaking and who would not be easily swayed in his considerations by the vilification of Sir Thomas Bouch in the press.

Bouch denied any responsibility for the disaster which he referred to as a tragic accident and his lawyers claimed that it must have been caused either by the train travelling too fast or by it being derailed after hitting an obstruction, but no evidence could be found for either of these scenarios.

Bouch was later to say that he believed the train to have been simply blown from the bridge by hurricane force winds that had never been seen before on these shores. Under cross-examination however he was forced to concede that cheap and shoddy materials had been used in its construction and that maintenance of the bridge had been irregular and often neglected, though he insisted that had he been aware of this at the time he would have put an end to such practices.

He also had to defend his use of lattice high girders in the construction of the bridge all of which were found to have collapsed in the storm and deny the accusation that he had not taken into account the possibility of extreme weather conditions or completed any specific scientific tests into potential wind velocity instead making assumptions based on past experience.

The Court also heard evidence from passengers aboard a train that had passed over the bridge just an hour before the ill-fated Express travelling from Edinburgh who had described in frightening detail how the bridge had swayed from side to side and of being violently thrown around the carriages like rag dolls. Questions were invariably asked as to why given such experiences the trains were not cancelled and the bridge closed for the night?

The Court of Inquiries findings were unequivocal: “The fall of the Bridge was occasioned by the insufficiency of the cross bracings and its fastenings to sustain the force of the gale, and that had the Bridge been properly constructed it would have withstood the storm that night.”

Henry Cadogan Rothery in his summing up was to add that he was clear in his mind that the Bridge was “badly designed, badly built, and badly maintained.”

The evidence against Bouch was damning and he was widely held to blame for the disaster but his recent knighthood was a source of embarrassment, so the Court declined to hold him directly responsible. As a result, the verdict a ‘tragic Act of God and no charges were brought.

Following the end of the Inquiry, Bouch immediately set about reinforcing the bridge he had recently constructed at the South Esk Viaduct, but his reputation was now such that the Inspectors unconvinced by its viability decided to demolish it entirely. In the meantime, his plans for a bridge across the Forth of Firth were quietly shelved.

Sir Thomas Bouch whose health was seen to visibly deteriorate during the Court proceedings died on 30 October 1880, just ten months after the Tay Bridge Disaster. It was said that vilified and with his reputation in tatters he did so a broken man.

Tagged as: Victorian

Share this post: