The Black Death: Brink of the Apocalypse

Posted on 1st January 2021

In 1346, the port city of Caffa in the Crimea on the shores of the Black Sea was a major commercial centre and trading post between East and West. It was a Christian city under the control of Genoa, and it was rich, and it was thriving. That same year it was besieged by the seemingly unstoppable Mongol Horde but surprisingly the city was holding out when in early 1347 the Mongols suddenly abandoned the siege.

It appeared their army had been hit by the plague but before departing they catapulted their plague victims over the walls of the city in an early example of biological warfare. Those defending Caffa were relieved they had gone but they could not have imagined the horror that they had left behind.

Trade routes throughout Western Europe were well-established by the mid-fourteenth century and spices, silks, and furs from the East were pouring into the cities of Italy before being exported far and beyond across the Continent of Europe - trade was good, life was good, and Medieval Europe was prosperous as never before, but all this was about to change.

In October 1347, a flotilla of 12 Genoese merchant ships arrived in the ports of Sicily from the East, sparsely crewed many aboard were already very sick it seemed when upon inspection it was found that the ships hold was crammed with dead bodies. Horrified at what they had found the Sicilians refused to allow the remaining sailors to disembark or for their cargoes to be unloaded. Instead, they ordered them to leave.

Some of these ships would later reach Venice and Genoa itself, and in January 1348 one of them moored ghost-like off the coast of Marseilles. The bubonic plague, or yersinia pestis, carried by fleas on the backs and in the fur of black rats, had arrived in Western Europe becoming the most lethal pandemic known to mankind which in just three years killed around half the population of the Continent, some 20,000,000 people, bringing it to the brink of the abyss.

The bustling port cities and commercial centres of Italy full of people from many countries going about their business were to prove the perfect breeding ground for the vile contagion to spread and very soon people began to come down with a flu-like fever; swellings known as buboes appeared on their neck, groin, and under their armpits. They vomited, coughed up blood, and invariably within 48 hours they were dead. Indeed, people were soon dying in their thousands and panic began to spread. A young lawyer from Piacenza, Gabriel De Mussis felt compelled to record the arrival of this diabolical plague:

"I have been urged to write what happened here, every city, every settlement and every place was poisoned by the contagious pestilence. When one person contracted the disease he poisoned his entire family."

The poet and future author of The Decameron, Giovanni Boccaccio, also wrote at this time:

"The condition of the people was pitiable to behold. They sickened by the thousands daily, and died unattended and without help. Many died in the open streets, others dying in houses made it known by the stench of their rotting corpses. Consecrated churchyards did not suffice for the burial of vast multitudes of bodies, which were heaped by the hundreds in vast trenches."

Another observer wrote:

"They died by the hundreds, both day and night, and all were thrown in ditches and covered with earth. And as soon as those ditches were full more were dug. And, I, Agnolo di Tura, buried my five children with my own hands. And so many died all thought it was the end of the world."

Carried by the rats the disease spread rapidly and could be transmitted to humans by a simple bite while physical contact between people, a sneeze or even the merest droplet from an infected person’s mouth could prove lethal.

The medical profession had no knowledge of the plague’s origin, how it was spread, or how to treat it. They believed it was caused by the Miasma, or foul and putrid air the result of human waste and rotting corpses. If the stench and foul smell of putrefaction was the cause then it seemed obvious that in sweet smells must rest the cure, and so people began to carry flowers on their person, hang them around their neck, and hold them to their nose.

But flowers made no difference neither did the clearing of human and animal waste from the streets or the shuttering up of plague victims in their homes, the burning of their clothes, or the burial of the corpses in deep pits. The best medical minds were at a loss what to do as were witnessed by the myriad of increasingly bizarre cures that were to be tried and found wanting.

The first symptoms of the plague, the high temperature and general nausea, would cause unease within a family. If it was followed soon after by the swelling of the lymph glands and severe skin discolouration, panic would set in.

If the patient could afford one the attendant physician would first lance the buboes before cutting them open to permit the disease to leave the body. A mixture of tree resin, white lilies, and human excrement was then applied to the cuts.

Also, commonplace was the sweating where the patient would be stripped naked and wrapped tightly in a blanket soaked in cold water. It was believed the sweating that would result would draw out the corruption that lay within.

Some also believed that if a live pigeon had its belly torn open to discharge its innards onto the victim’s swellings, then its blood and guts would purge them of their infection.

Another popular method of cure was the Water and Vinegar Treatment where again the patient would be stripped naked and washed in rose water before having vinegar rubbed into every part of the body. They would then be put to bed where invariably they would die.

Medicine was also prescribed and the recipe for one such remedy was:

"Roast the shells of newly-laid eggs. Ground the roasted shells into powder. Then chop up the leaves of marigold flowers. Put the marigolds and egg shells into a pot of good ale. Add and warm over a fire. The patient should then drink every morning and every night. Should they keep the contents down then they shall have life."

None of these solutions worked, neither did devotional prayer and increased piety or charitable works and the repentance of one’s sins. In their desperation people soon began to turn to magic and witchcraft but the suggestion that you place a live hen next to the tell-tale swelling to draw out the pestilence and then drink a cup of your own urine was no more successful than the prognostications of the increasingly bemused and terrified physicians who soon began to refuse to treat plague victims altogether.

A few continued to try however, among them Gentile D'Aforino, the Chief physician at the University of Perugia who continued to treat the sick despite the evident danger this entailed. He wrote:

"This pestilence, or epidemic, or whatever else you wish to call it, is more than anything I have ever seen before, no disease of comparative malignancy has ever been witnessed."

He continued to visit plague victims in their homes where despite studying the symptoms closely, he remained perplexed and bemused: "The immediate and particular cause is a certain poisonous material that is generated from the heart and the lungs. My job as physician is not to worry about the heavens but treat the symptoms of the sick and do what I can for them."

But he could do little.

Physicians at the time believed that the body should be used to heal itself. D'Aforino, who advised his patients to sleep on their side to keep the body in balance and to eat more lettuce, died on 18 June 1348, of the plague.

As the Black Death continued to spread ravaging the Continent and reaping its harvest of human souls the Catholic Church began to lose its spiritual authority. Pope Clement VI, whose own love of life's more earthly pleasures had itself come in for much criticism, had declared the plague God's Will and that only through ever greater devotion and the power of prayer would the people be delivered. But the cure did not come and neither the Pope nor the Church could explain why God had willed it so. It could only be because of greed, the desires of the flesh, and the lack of piety, they said. But this did not explain why thousands of priests, monks, and nuns had also fallen victim.

Soon it wasn't possible to find any member of a religious order who was willing to succour the dying, provide the sacraments, or give the last rites.

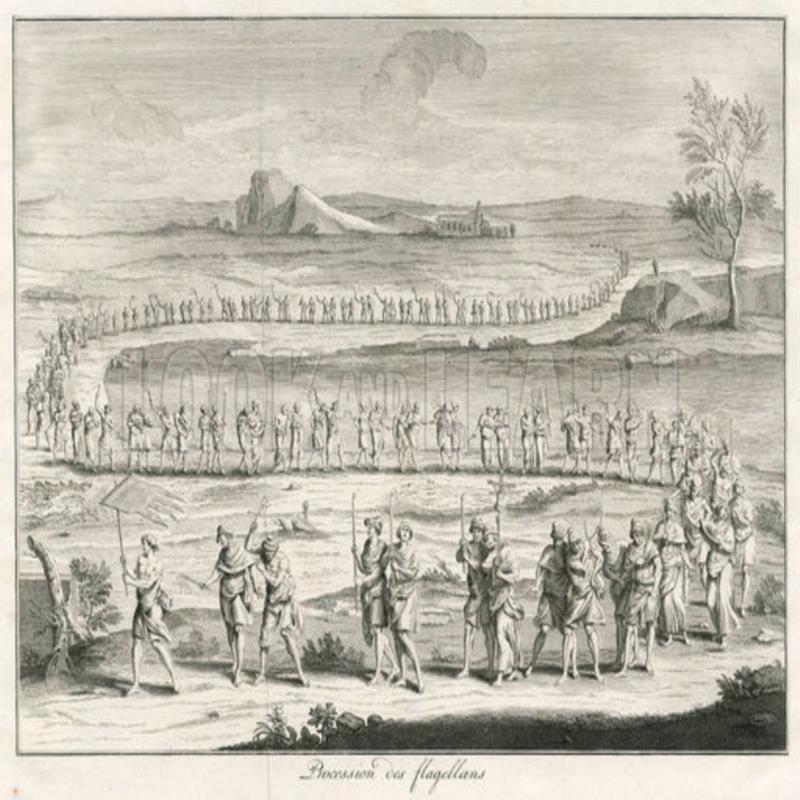

In 1349 a new phenomenon appeared - the Flagellants. They were a radical sect within the Church who adopted self-mortification as a physical demonstration of their piety.

They first appeared in Germany where they travelled from town-to-town whipping both themselves and those who flocked onto the streets to observe their procession and seek their blessing and redemption into a bloody frenzy. As the men took to whipping themselves the women dipped their handkerchiefs in the blood and smeared it on their foreheads. One observer described the scene:

"We witnessed a performance of devout processions with the chanting of litanies, men and women alike, many barefoot, others wearing hair shirts, or smeared with ashes, processed with lamentations and tears. They bet themselves cruelly and whipped themselves until they bled."

The Flagellants travelled across plague ravaged Europe and on 29 September 1349 arrived in London. There, Robert of Avesbury watched their procession:

"About Michaelmas over six hundred men came to London from Flanders. Sometimes at St Paul's and sometimes at other points in the city they made two daily public appearances wearing clothes from thighs to ankles but otherwise stripped bare. Each wore a cap marked with a red cross in front and behind. Each had in his right hand a scourge with three tails. Each had a knot and through the middle of it sometimes with nails. They marched naked in a file one behind the other and whipped themselves with great fury on their naked and bleeding bodies. Four of them would chant in their naked tongues and the rest would respond like a litany. Thrice they cast themselves down upon the ground stretching out their arms like the sign of the cross. The singing and the chanting would continue as others stepped over the prostrate them whipping their bodies as they did so. Then each put on their customary garments and returned to their lodgings."

By 1350 it is believed that the Brotherhood of the Flagellants had as many as 800,000 adherents but they were soon deemed to represent a direct challenge to the authority of the Church and within two years they were to be declared a heresy. But they were also a menace to those who flocked to watch them for they merely helped carry the plague to areas it had not yet reached, and many towns soon began to close their gates to them.

By the end of 1347 the Black Death had ravaged Italy and much of southern Europe and was moving north.

In Venice 90,000 people had died their bodies being hurriedly buried on the islands in the bay. In Florence it was 50,000 or more than half of the city’s entire population. In Piacenza 60 priests died in just three days, whilst in Siena work on its Cathedral had to be halted because there was simply no one left to carry it out.

Having reaped its terrible harvest in Italy the Black Death now moved on to do likewise in France, Germany, and the Low Countries. In Paris the population was reduced by half to under 30,000, 60% of people in Norway were to die, while of the 170,000 settlements in Germany 40,000 ceased to exist altogether.

No one knew what to do and in Milan the homes of the sick were sealed, and no one permitted to enter or leave. If those who were related to the victims were believed to have been in contact with them since they had fallen ill, then whether sick or not they too would be sealed in with the dying.

Meanwhile in Avignon, the effective seat of the papacy from 1309 to 1377 following the Great Schism with Rome that was to continue until 1423, the Pope was in despair. Not only did he fear for his own life, particularly as it had been shown that those in holy orders had no greater protection against the plague than anyone else, but the moral authority of the Church and the civil authority that protected it had broken down. When priests could be found who were both available and willing to take services no one turned up. Indeed, priests were often attacked in the streets and churches looted.

People, believing that God had forsaken them no longer heeded the call of the Church for ever-greater devotion but instead lived life for the day. They drank, they stole, they raped, and they murdered. There was nothing to fear anymore, there were no Princes, there were no Courts, and they had already it seemed been condemned to hell.

So many deaths had there been in Avignon itself that the Pope had already consecrated the River Rhone so that it could be used as a depository for the bodies which would then be carried upstream.

The personal physician to Pope Clement VI in Avignon was Guy de Chauliac, the leading medical practitioner of his day. When the Black Death reached the city, most doctors fled but either out of dedication to his profession or simple curiosity he remained treating plague victims daily, studying the symptoms and carrying out autopsies on the dead.

In the summer of 1348, he too was struck down by the plague and abandoned by family, friends, and colleagues for six weeks he lay seriously ill treating, himself as best he could and lancing his own buboes. Miraculously, he survived but still, he did not flee remaining in Avignon to continue his studies and tend to his patients within the Papal Court.

Through his observations de Chauliac was able to distinguish between two types of plague, the bubonic that was spread by the bite of fleas and infected the lymphatic glands, and the pneumonic that infected the respiratory system and was spread by human contact. He advised the Pope to isolate himself in a single room, avoid contact with other people as much as possible, and to remain seated between two roaring fires. Heat, he believed, aided purification. It appeared to work for though half of the Cardinals in Avignon died during the plague neither, the Pope nor any of the Cardinals and Bishops treated by de Chauliac did.

Had de Chauliac, who was the only physician to recognise the plague as a contagion, found a way to treat it? If he had then he did not realise it himself, or know what it was that had made the difference. For the vast majority of people however there was no hope of cure and they continued to die in their hundreds of thousands.

As the belief grew that the plague was a putrefaction of the air blown across the Continent as a vile wind by a vengeful God then so did the view that there must be a reason for the Almighty's wrath. A scapegoat needed to be found and there was an obvious one living within their midst - the Jews. To permit those who denied the One True God and were responsible for crucifying his Son upon the Cross to live freely amongst them was an obvious heresy. They sought to destroy Christendom and now the people were being punished for doing nothing to prevent them.

Jews across Europe were now accused of contaminating food with deadly toxins and of poisoning the wells. The wives and daughters of prominent Jews were arrested and put to the torture as it was believed easier to force women into a confession and in many places there was not even a semblance of recourse to the law. For example, in April 1348, the Jews in Narbonne and Carcassonne were simply dragged from their homes and summarily burned at the stake. In February 1349, 2,000 Jews were murdered in Strasbourg. In August 1349, all the Jews in both Mainz and Cologne were exterminated and by 1351 more than 200 Jewish communities across Europe had been wiped out.

There was also a more down-to-earth and sinister reason for the attack upon the Jews. It not only provided the opportunity to seize their property but also to wipe out a debt by killing your creditor, and many Jews were put to death long before the plague ever reached the town concerned.

On 24 June 1348, at the port of Melcombe Regis near Weymouth, the Great Pestilence at last entered England. It arrived on a ship from Gascony that had a sick sailor aboard and in no time at all it had spread to the city of Bristol. With more than 20,000 people crammed into its narrow streets, with no sanitation, wild animals allowed to roam free foraging for food, and everyone taking water from the nearby river it provided the ideal conditions for the contagion to spread. Within just weeks the city was devastated with 22 of the city's 50 Town Councillors dead and those merchants who left the city laden with goods for sale soon spread the disease throughout the country.

People in England were aware of the terrible events on the Continent but believed they had been spared because of their greater devotion to God. It didn't take long for such illusions to be shattered and as the plague ravaged the countryside people fled to the towns and cities, as it ravaged the towns and cities they fled back to the countryside, everywhere taking the disease with them. By September it had reached London which with a population of more than a 100,000 people crammed into tiny houses with little ventilation and raw sewerage running down its streets saw the contagion kill at a rate even faster than that seen on the Continent. Indeed, so many people were killed in such a short space of time that mass burial pits were dug at Spitalfields for the hasty disposal of the bodies.

It was traditional for the dead to be buried with their feet facing east and towards Jerusalem so that they could stand before God at the Last Judgement. Now they were just tossed pell-mell and without ceremony into a pit, some with breath still in their body.

Just as elsewhere people in England believed that the pestilence was the result of putrid air dispersed across the country by a vengeful God and therefore it appeared self-evident that the foul smells that resulted from it needed to be removed. At the height of the Black Death King Edward III wrote to the Lord Mayor of London: "Cause the human faeces and other filth lying in the streets and lanes of the city to be removed with all speed to places far distant, so that no greater mortality may be caused by such smells."

The Town Council was forced to regretfully inform the King that this could not be done as all the street cleaners were already dead.

The King, his family, the Royal Court, and other notables soon fled the city to their country estates. Though flight to the countryside was no guarantee of survival, the plague was just as virulent and devastating there as elsewhere, and the plague itself was no respecter of rank, but being able to isolate themselves and not encounter others meant that the mortality rate among the nobility was always lower than among the other classes of society.

In London the impact of the plague was as great as it had been anywhere in Europe. In just a few months more than 50,000 had died including two ex-Chancellors, three previous Archbishops of Canterbury, the Abbot of Westminster, and 27 of his monks. Indeed, the priesthood was so decimated that the Bishop of Bath and Wells ordered that women be permitted to provide sacraments to the dying before he too succumbed to the disease.

From London the Great Pestilence soon spread north with the worst hit areas being those with ports who had trade with the Continent, the southern counties, and East Anglia. Some of the more isolated counties away from the main routes of communication and travel fared less badly but there was no region that remained unaffected. Everywhere in the country farms lay abandoned, crops uncultivated, and livestock lay dead in the fields. In some places villages simply ceased to exist and entire regions were effectively depopulated.

A Scottish Army which had crossed the border with the intention of taking advantage of the Auld Enemy's distress was forced to abandon its invasion when it too came down with the sickness, retreating into Scotland and taking the disease with it.

In just two years the Black Death had reduced the population of England alone by 45%, so out of around 6 million people 2,750,000 are estimated to have died with the mortality rate in some places being as high as 90%, though in others it could be as low as 15%.

In Ireland, which the plague reached later than most other countries in December 1348, more than 14,000 died in Dublin alone and the mortality rate in Kilkenny was 100%. One man who recorded the impact of the plague in the area where he lived was in no doubt that he was witnessing the end of the world. He kept a diary before he too contracted the disease. The last entry revealed his despair:

"I, Brother John Clin of the Friars Minor of Kilkenny have written in this book of the notable events which befell at this time, so that such deeds should not perish with time, or be lost from the memory of future generations. I leave parchment for continuing the work in case any should still be alive in the future, and any Son of Adam can escape this pestilence and continue the work thus begun."

There were no further entries written in his hand, apparently, he too had succumbed.

By the winter of 1350, the Black Death had ceased almost as swiftly as it had begun with the number of plague victims decreasing significantly, though it was to reappear again in Russia the following year. It seemed to all, that God's wrath had been placated but in just three years it had ravaged the European Continent, killed millions of people, caused a breakdown in law and order, created economic chaos, moral decay, damaged the authority of the Church, and brought much of the known world to the very brink of the apocalypse. Only the Kingdom of Poland, somewhat bizarrely, had been spared.

The Black Death had not just been a European phenomenon of course, the invincible Mongol Horde that had done so much to spread the disease was so weakened by its impact that it was forced to return to its homeland defeated not by men but by fleas.

The plague was to spread throughout the Middle and Far East, and to North Africa where it killed 40% of the population of Egypt, and it is estimated that as many as 200 million people died worldwide.

The Black Death was to leave behind it a profound legacy, none more pronounced than in England. Many peasants who had previously owned little now came into possession of plots of land bequeathed by dead relatives that elevated them socially and, in some cases, provided them with small village fortunes.

The shortage of labour that now prevailed also witnessed the breakdown of the old feudal system and presaged the end of serfdom with peasants were now able to demand two, three, even four times more than previous for the cost of their labour.

The nobility aware of what was occurring demanded of King Edward III that he act to prevent it. He did so with astonishing swiftness issuing the Ordinance of Labourers on 18 June 1349 at the very height of the Black Death. This pegged wages to their pre-plague 1346 level and Tribunals were established the length and breadth of the country to fine those peasants who dared to demand more for their labour and penalise those landlords who were willing to pay it.

This law was reinforced in 1351 by the passage of the Statute of Labourers which also inflicted harsh penalties upon those who were unwilling to work. But laws passed in Parliament could not alter the law of supply and demand and if a peasant did not receive the wages he demanded then he would simply up-sticks with his entire family and move to the estate of a landlord who had a firmer grip on the new economic reality, that if you wanted your crops harvested and your livestock tended to then you had to pay.

Those who had survived the ravages of the Black Death had benefited from it for it changed the workforce forever. A new, often itinerant, upwardly mobile working class, and a prosperous middle class village elite had been created, and both were willing to fight to maintain their new-found status as they were to prove during the Peasant's Revolt of 1381.

The Black Death also left a cultural legacy in art, music, and literature with depictions of death, particularly death in life were now everywhere to be seen. It manifested itself in nursery rhymes such as: "A ring, a ring o'roses, a pocketful of posies, atishoo atishoo we all fall down."

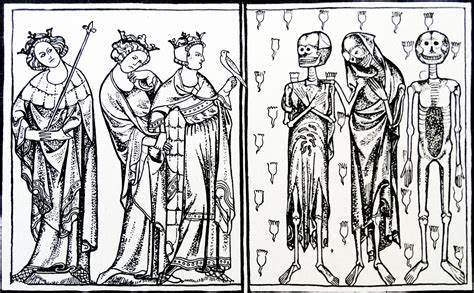

Depictions of the Danse Macabre where cadavers and the living linked arms to dance together in the face of death became commonplace.

There were Transie Tombs or two-tier graves the upper tier of which showed the deceased in all his living glory dressed in fine clothes and jewellery whilst below lay his cadaver decayed and eaten through with worms and maggots.

And everyone now knew the story of the Three Living and the Three Dead where three handsome young Princes travelling together encounter three corpses in various stages of decay. One of the Princes remarks:

"I'm afraid, lo what I see, methinks these are devils be."

The corpses replied:

"Such as I was you are, and as I am you shall be - for I was welfare, for God's love beware - know that I was head of my tribe, Princes, Kings, and Nobles, royal and rich rejoicing in wealth, but now I am so hideous and bare that even the worms disdain me."

Death had become the Great Leveller.

Images of the Grim Reaper as the Angel of Death became part of folklore and Plague Doctors in their beak like masks filled with aromatic herbs to ward off the putrid air a familiar sight.

The plague of course did not simply go away in 1350, and it would return time and time again to reap its grim harvest of human souls, and millions more lives would be lost as a result. The last significant outbreak in Britain, for example, was the Great Plague of London in 1665; in Europe it was to be the epidemic that struck Marseilles in 1720 but deadly though these outbreaks were they never had the same impact as the Great Pestilence, the Great Mortality, or the Black Death as it was spoken of with dread had between in 1348-50.

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval

Share this post: