The Bonnie Prince and the '45

Posted on 20th March 2021

Charles Edward Louis John Casimir Silvester Severino Maria Stuart, better known to history as Bonnie Prince Charlie was born in Rome on 31 December 1720. He was the son of the Stuart claimant to the English throne, James Francis Edward Stuart. His mother, Maria Clementina Sobieski was the granddaughter of the Polish King John III. So he was not just of Scottish but also of Polish ancestry and raised in the Eternal City was culturally, intellectually and temperamentally an Italian.

His father, the Old Pretender, was the son of the last Stuart King of England James II, who had been deposed by William Prince of Orange in 1688 and since the old Kings death he had made several attempts to regain the throne.

In 1708 he had been thwarted in his ambitions by an impromptu attack of measles. He tried again in 1715 but despite an indecisive battle fought at Sheriffmuir was so disappointed by the response of the Highland Clans to the possibility of a Stuart Restoration that he left a terse note telling his supporters to look to themselves and took ship back to France.

Once safely back on the Continent he established a Court in Exile but his attempts at open rebellion had come to an end. In December 1743 he named his son Prince Regent and gave him full authority to re-establish the Stuart Dynasty in England by any means available to him. The young Charles Edward took his new responsibility seriously and was determined to succeed where his father had failed and do so honourably by force of arms – it seemed to trouble him little that he had no of arms and no army with which to do so.

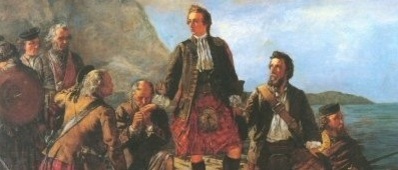

On 23 July 1745, the soon to be ‘Bonnie Prince’ landed on the Island of Eriskay in the Hebrides with just 7 companions. He had little to offer the Highlanders in return for their support, just the desire, he said, to make Scotland happy and the promise of a French Army to come.

The venture was foolhardy to say the least and the initial response to his arrival appeared to reflect that. It was less than enthusiastic with many of the Clan Chieftains reluctant to rally to his cause, but he was a Stuart, a Catholic and at just 25 years of age full of manly vigour. He also had agents working on his behalf and by the time he raised his Standard at Glenfinnan on 19 August 1745, some 1200 men of the MacDonald, MacDonnell and Cameron had pledged themselves to his cause - the Clan’s had rallied, after all.

The Prince continued to gather support as he advanced south and met little, if any, resistance. He was to easily capture the towns of Coatbridge and Perth and on 11 September he occupied Edinburgh, though he was unable to capture the Castle. On 21 September, the Jacobites as they were known, encountered the only Hanoverian Army in Scotland of any note.

Sir John Cope with 2,500 men had set up camp near the town of Prestonpans. He was an experienced and energetic soldier but conventional in his thinking and he had expected to meet the Jacobites on the field of battle when both armies had formed up in the normal way.

However, Sir George Murray, the ablest of the Jacobite commanders had ordered a forced night march which enabled the Jacobite Army to emerge out of the mists and attack at first light without warning. Sir John Cope was taken completely by surprise and the Hanoverians with sleep still in their eyes and reduced to abject terror by the blood-curdling cries of a full-bloodied Highland charge broke and fled in panic; in the rout that followed more than 400 were killed and a further 1500 taken prisoner.

The only Hanoverian Army in Scotland had been utterly destroyed for the cost of just 30 Jacobites killed and 70 wounded.

General Cope was later cleared at a subsequent court martial of negligence but with his reputation in tatters he was quick to blame the men under his command declaring his English soldiers too scared to stand up to the ferocious Highlanders and that his successor in Scotland would fare no better than he had.

It mattered little as for the time being at least, Scotland belonged to the Bonnie Prince.

For five weeks the prince remained in Edinburgh receiving letters of congratulation and delegations of well-wishers but little practical support. The simple truth was that most of Scotland still opposed him but that would change once he regained the throne of England for his father. At a heated Council of War, he argued vehemently that the Jacobite Army must invade England itself, that the Hanoverian’s were in disarray and that with their best troops away in Flanders London lay open to them. He had also received reports that Tories in England were preparing to flock to his banner and reiterated his claim that a French invasion was imminent. It was, he said, now or never.

Lord George Murray was sceptical that any such support either in England or France would materialise and argued instead that the prince should remain in Scotland and ensure himself of its support first. The point at issue was a stark one, consolidate what they already had or risk everything they had gained on the throw of a dice. There was little for room manoeuvre and the two men and their supporters would argue late into the night.

In the end the prince would get his way but only by 1 vote.

On 3 November 1745, the Jacobite Army only 6,000 strong but expecting to rally support on their march south set out for London. The news sent the capital into a panic as people fled the city, shops were boarded up, there was a run on the pound and preparations were made should the King need to make a hasty departure. Yet for all the nervousness in London and elsewhere at the prospect of a Stuart Restoration there was little to panic about. Support for the Jacobite cause was slight, the English Tories did not rally to the prince’s cause as expected and only in Manchester did some 250 disgruntled Episcopalians join the Scots army. Despite popular loathing of the Hanoverian Monarchy there was little enthusiasm to see a Catholic and more pertinently a Stuart back on the Throne of England.

Despite the indifference of the people to the Jacobite cause its Army further diminished by having to leave garrisons at Manchester and Carlisle continued its advance south deep into a hostile country with no hope of reinforcement, and their position became more perilous with every step. General Wade was in hot pursuit from the north-east, the Army of the King’s youngest son the Duke of Cumberland barred the route to London while the city itself had been transformed into an armed camp.

It had only been the masterful manoeuvring of his forces by Lord George Murray that had allowed the Jacobites to evade the various traps that had been laid for them and by 4 December they had reached the town of Derby, just 125 miles from London. But he was also convinced that they were heading for disaster and now demanded another Council of War where serious questions were raised: where was the support of the English Tories? Where was the promised French invasion?

The prince was forced to admit that his assurances had been so much hot air but he insisted that once London was reached the French invasion would surely come. Lord George Murray argued vehemently that in London they would be trapped by superior forces with more arriving all the time from the Continent and that their return to Scotland would be cut off. This time the Clan Leaders ignored the impassioned pleas of their Prince and voted unanimously to return to the Highlands. Denied what he believed to be his destiny the prince threw a tantrum and sulked on his horse all the way back to Scotland.

Once again through a series of brilliant feints Lord George Murray was able to evade his pursuers but he was forced to abandon the garrisons at Manchester and Carlisle to their fate and they were to suffer grievously as a result.

Lord George and the other Clan Leaders now tried to persuade the prince to abandon his dream of a Stuart Restoration in England and instead establish himself as King of an independent Scotland. But in this he had little interest he merely sought to use Scotland as a stepping-stone to re-capturing England for his father, but he also knew that this could not be achieved without the support of the Clans. Broiling with frustration he now forced the city of Glasgow to replenish his army and wasted men and resources on a pointless siege of Stirling Castle.

In the meantime, the Hanoverian Army in Scotland had been reinforced to 7,000 men and had a new Commander in Sir Henry Hawley. He saw in the Prince’s siege of Stirling Castle an opportunity to attack the distracted Jacobite Army but it was to be Lord George Murray who reacted first. He knew the 67 year old Sir Henry to be an arrogant and complacent man with a liking for the bottle who was unlikely to have made adequate preparation. So, adopting tactics similar to those he used at Prestonpans he once more unleashed his Highlanders early in the morning upon the still slumbering Hanoverians.

Hawley, who had housed himself some 2,000 yards behind his army’s encampment at first refused to believe that the Jacobite Army was upon him. When he did at last react it was too late as leading his cavalry in a counterattack 80 Dragoons were killed in the first volley of gunfire and the rest quickly fled riding over the Glasgow Regiment that was following close behind. However, unlike at Prestonpans not all the Hanoverian troops fled from the terrifying Highland charge and Hawley was able to extricate his army intact even if it was in some disarray.

Yet again, Lord George Murray had won a great victory with the Hanoverians losing more than 350 killed and 300 captured for the loss of just 50 Highlanders with a further 80 wounded. But at Falkirk the English had not run away.

The prince, who by this time refused even to acknowledge let alone speak to Lord George did not try to press home his advantage but instead continued the pointless siege of Stirling Castle.

Sir Henry Hawley was removed from command of the Hanoverian forces in Scotland and replaced by the Duke of Cumberland who had brought his own army north to complete the task of destroying the Jacobite threat once and for all.

Criticised for failing to exploit the opportunity provided by Lord George’s victory at Falkirk to eliminate the Hanoverian presence in Scotland the Prince decided to take sole and complete command of his army declaring that there would be no more Councils of War, either the Clans followed him, their Prince, or they did not.

Increasingly disenchanted with the Clan Chieftains the Prince turned to the Irish in his entourage for advice in particular his Adjutant-General Walter O’Sullivan, and it was he who would choose Drumrossie Moor near Culloden as the place to confront Cumberland’s Army.

It was clearly a mistake, and the Clan leaders knew it was a mistake. But the Prince was no longer listening to them. The terrain at Culloden could barely have suited Cumberland better; its low stone walls provided cover for his own troops while the open and treeless ground beyond provided a wide arc of delivery for his artillery and was perfect for cavalry of which the Jacobites had none. The Clans would also be attacking uphill which would only serve to negate the ferocity of the Highland Charge.

The Clan leaders begged the prince not to give battle at Culloden and some suggested that his increased liking for the bottle was clouding his judgement. But the Prince would have none of it. He would “trust in God,” he said.

On the night of 15 April 1746, the Hanoverian encampment resounded to music and much merriment as the troops celebrated the Duke of Cumberland’s birthday. Extra rations had been distributed and the rum flowed freely at the duke’s expense. The soldiery were relaxed and happy making Lord George Murray believe it the perfect opportunity to repeat the success of Prestonpans and that with a forced night march they could fall upon the Hanoverian camp at first light before it had even awoke let alone sobered up.

Despite barely being on speaking terms with Lord George the Prince decided to give the go-ahead for the plan.

Because of the failings of Walter O’Sullivan, who as Quartermaster had done nothing to secure the food supply many of the Highlanders had not eaten for days. They were cold, dishevelled, and weak from hunger and now they had to complete a forced march in the dead of night in wet, freezing conditions and then fight a battle at the end of it.

The hastily arranged march soon descended into chaos as tired men, wet-through and frozen stumbled over one another in the darkness or became stuck in the mud and disappeared into bogs. By the time they arrived at the Hanoverian camp it was already daylight, and the troops were awake, armed, and going about their business. Lord George had no choice but to abandon the attack and march his men straight back from whence they had come.

The following day 16 April, the Duke of Cumberland marched his troops onto Drumrossie Moor and the Jacobites, many of them still exhausted from the march of the previous night, lined up to meet them.

Lord George Murray, fearing the worse, had reinforced the Jacobite Army with 800 men of the Ecossais Royaux (Royal Scots) and Irish Piquets, exiled supporters of the Stuart claim to the throne who had experience of fighting in the French Army. These would be held in reserve to cover any withdrawal he thought inevitable.

It was the Jacobites who fired first but their artillery barrage was short, ineffective, and quickly silenced. The Hanoverian artillery by contrast was deadly. It was manned by gunners with years of experience fighting in Flanders and for 30 minutes it raked the Jacobite lines cutting swathes in its ranks. Impotent in the face of the barrage the Clan Chiefs begged the prince to order the charge. Far behind the front-line he refused insisting that he wanted the Hanoverians to break formation first. It was to be a costly mistake for in that short 30 minutes more than 500 Highlanders were cut down.

Frustrated and unwilling to take any further needless casualties some of the Clans began to advance of their own accord. Seeing this, the prince at last gave the order for the charge to begin but with some already engaging the enemy it was too late now to organise the full-on, rush of a Highland Charge yet even sporadic and uncoordinated it remained a sight to behold and terrifying to those forced to face it.

Clan Chattan which had been the first to attack had been halted by grapeshot and desperately scrambled to find cover where they could. Meanwhile, the MacDonald Clan which was traditionally positioned in the centre, the place of greatest honour in any Clan battle formation had been moved to the left. Offended by the insult they now refused to charge at all. But the left-flank of the Hanoverian Army was hit hard with the brunt of the attack being taken by two regiments of foot, Barrell’s and DeJean’s.

In no time at all Barrell’s line had been broken and his regiment smashed. He had lost 17 men killed, 103 wounded, and the colours had been taken. Likewise, DeJean had suffered 14 killed and 68 wounded in a matter of just minutes and his line was close to disintegration.

Seeing his left-flank on the point of fracture and in danger of collapsing in on itself, the Duke of Cumberland was quick to react. He immediately filled the gaps in the rapidly thinning ranks with the 1,000 men of Semphill’s Brigade. Among these was the regiment of Major James Wolfe, the future Hero of Quebec.

The Duke of Cumberland was marshalling his troops well and despite the ferocity of the Highland charge the Jacobites had been unable to make a breakthrough. Their last hope lay with the MacDonald’s. Addressing them directly the prince begged them to participate in the battle and eventually they agreed; but they only did so reluctantly and when the charge came it was half-hearted and stopped short of the Hanoverian lines where keeping their distance they jeered the English but refused to come into contact with them. Eventually under intense fire they broke and began to flee the field. Witnessing the flight of the MacDonald’s, Lord George Murray brought forward the Eccosais Royaux and Irish Piquets who exchanged volley fire with the Hanoverians but were unable to stop the Highland retreat from becoming a rout.

The prince now rode among his fleeing troops begging them to remain and fight – “For God, for your Prince,” he cried, but to no avail. Finally, he was escorted from the field but as he departed a Clan Leader was heard to shout – “That’s it, run you cowardly Italian.”

The Battle of Culloden had been lost but not necessarily the Jacobite cause for despite the high casualties 1,500 killed, 1,000 wounded and 157 captured, a whole third of the Jacobite Army had not been present at Culloden. Hanoverian casualties by contrast were relatively light just 50 killed and 259 wounded.

Some of the Clans tried to rally after Culloden and some 1500 men gathered at Ruthven Barracks to await orders with others on the way. They could they believed still sustain a guerrilla campaign in the Highlands. Instead, they received an order from the prince that echoed the terse message sent by his father 30 years earlier: “All is lost and each man must shift for himself as best he can.” With no direction and shorn of leadership the Clan Army dispersed.

In the days immediately following the battle Cumberland’s troops scoured the battlefield looking for wounded Scots to kill. He had fortified their resolve for the slaughter by telling them that the Jacobites had ordered that no quarter should be given, though no proof of any such order has ever been found.

In the meantime, the prince had made his way to Arisaig on the west coast of Scotland from where he took ship to the Island of Benbecula in the Hebrides and with a £30,000 price on his head, Government troops in hot pursuit and at a loss what to do and frequently drunk, his position was precarious indeed.

A Jacobite loyalist, Flora MacDonald, now came to his rescue disguising him as her Irish maid Betty Burke, she took him into her household before procuring a boat to take him to the Isle of Skye from where on 19 September 1746 he managed to take a ship which ferried him to safety in France.

What the Prince left behind was a country prostrate and the last tribal society in Western Europe destroyed.

Whereas most of Scotland celebrated his demise the Highlands were left devastated as families were cleared from the land and their homes destroyed. Those Jacobites taken prisoner, 3,741 of them, were sent south to stand trial. Of these 120 were executed, 648 remain unaccounted for, and 936 were transported to the Colonies as indentured slaves. Most of the rest, including Flora MacDonald, were released in the general amnesty of 1747.

The captured Clan Leaders were to endure the fate reserved for traitors – to be hung, drawn, and quartered on Tower Hill.

Meanwhile, the Duke of Cumberland’s exacting elimination of Jacobitism and the Highland Clearances that were to follow over the ensuing years were to earn him the eternal enmity of the Highland Scots and the name “Butcher Cumberland.”

Following his return to mainland Europe the Bonnie Prince very soon ceased to be quite so Bonnie. Increasingly irascible and bad-tempered, frequently mired in scandal, and drinking too much he quickly became an embarrassment and further attempts at a French invasion and the Restoration of a Stuart Monarchy foundered on the prince’s habitual drunkenness. Indeed, in such bad ordure was he held that when his father died in 1766, Pope Clement XIII refused to bestow as would have been expected on his son the title King of England, Scotland, and Ireland.

Bonnie Prince Charlie, the Heir to the Stuart Crown, spent his final years in Rome drinking, whoring, and complaining that he had been betrayed by the cowardice of the Highland Clans and by the end of his life he was as much a physical ruin as the Scotland he had so many years before promised to make happy.

Postscript:

Clans who fought for the Prince:

Boyd, Cameron, Chisholm,Davidson Drummond, Farquharson, Fraser, Hay, Livingstone, MacBean, MacColl, MacDonald, MacDuff, MacFee, MacGillivray, MacGregor, MacInnes, MacKinnon, MacKintosh, MacIntyre, MacIver, MacLachlan, MacLaren, MacLean, MacNeil, MacNaughten, MacPherson, Menzies, Morrison, Ogilvy, Oliphant Robertson Stewart

Clans who fought against the Prince:

Campbell, Cathcart, Colville, Cunningham, Grant, Gunn, Kerr, MacKay, Munro, Ross, Semphill, Sinclair, Sutherland.

Clans which fought on both sides:

Murray, Elphinstone, Forbes, Keith, MacKenzie, MacLeod, MacTavish, MacMillan, Maxwell, Ramsey, Wemyss.

Clans which remained neutral:

MacQuarrie, MacDougall.

With the Highland Clans divided and the Lowland South largely united in opposition more Scots opposed and fought against Bonnie Prince Charlie than for him.

Tagged as: Georgian

Share this post: