The Chartists: Moral or Physical Force?

Posted on 18th January 2021

The Chartist Movement, the first and greatest political lobbying campaign of the nineteenth century emerged out of the informal gatherings of respectable and self-educated artisans that would later develop into the Corresponding Societies.

Primarily concerned with electoral and constitutional reform they believed that reasoned argument and polite persuasion would triumph where threat and riot had failed to alleviate either the condition of the distressed working class or lead to an extension of the franchise whereby concerned and responsible men such as themselves would have a greater say in the affairs of the nation.

But what began as the earnest desire of an emergent middle-class for greater representation in a just and fairer society soon developed into a mass-movement of the poor and dispossessed which would see the gentle art of persuasion in uncomfortable alliance with the bludgeon wielding men of violence and armed insurrection.

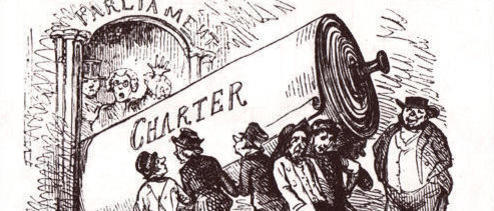

In 1837, William Lovett, a leading member of the London Working Men’s Association and the veteran campaigner Francis Place, drew up the People’s Charter, a six-point programme of political reform from which the movement would soon derive its name. It demanded:

1/ The Vote for every man twenty-one years of age or over and of sound mind.

2/A Secret Ballot.

3/ No property qualification for Members of Parliament.

4/ Paid Members of Parliament.

5/ Equal constituencies securing equal representation.

6/ Annual Parliaments.

Any suggestion of female enfranchisement at this time was not on the agenda and if it was considered at all it was quickly dismissed.

This People’s Charter, as it would become known, had evolved out of a sense of disappointment and even deeper frustration that the 1832 Electoral Reform Act which had been passed against intense opposition had been only partially successful. It had it was true, abolished the Rotten Boroughs (those constituencies that were the fiefdom of party placemen and government largesse) and provided greater representation for the towns and cities but the property qualification for electors remained and despite those eligible to vote rising from 400,000 to 650,000 the working-class majority remained virtually excluded.

The sense of grievance that emerged from what many considered a betrayal was only increased with the passage of the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, which abolished Outdoor Relief for the unemployed and destitute who in future to provide for themselves and their families would have to commit to the newly created Workhouse and its draconian impositions. This was at a time of increased rural unrest caused by the continued enclosure of the common land, the suppression of wages as a result of machine technology and improved agricultural practices that made farming less labour intensive.

As a consequence there was a mass-migration from the land to the already overcrowded industrial towns and cities which had made no provision for the increased population and urban life was to be no less miserable than the rural one they had left behind; poor food, polluted water, dank and dirty living conditions, and high mortality rates were their lot, but it did at least offer the opportunity of employment even if the hours were long and the wages low.

For those who remained on the land the choice was stark, to live in abject poverty and slowly starve to death or risk the wrath of the law by turning to violence and becoming a machine-wrecking Luddite.

The People’s Charter soon became the Standard Bearer for hope not just for those who desired political and constitutional reform but others who were desperate for fundamental social change; from the well-heeled banker and Member of Parliament Thomas Attwood and his Birmingham Political Union which believed gentle persuasion and the justice of their cause would provide the means whereby change could be achieved; to those who had experienced the harsh reality of working class life, the greed of the landowners and manufacturers, the obduracy of government, the penal attitudes of bloody-minded Magistrates, who believed that only direct action and the threat of violence would see them yield to their demands.

The disparate nature of the Chartists saw the fissures appear early between those who wished to emphasise the moral case and remain within the law and others who desired confrontation. So, Chartism as a movement was divided almost from its inception and it would be this split that would dictate its future development.

The path of persuasion and moral coercion advocated by Lovett, Attwood, and others, so often derided by mainly northern Chartists as our ‘namby-pamby lukewarm friends’ bore little resemblance to the mass-demonstrations and torch-lit processions occurring in the industrialised towns of the north throughout the latter part of 1838 and early 1839.

Indeed, the often inflammatory oratory of their leaders such as Feargus O’Connor and Richard Oastler stood in stark contrast to the cautious and reformist approach of those Chartists who believed in the moral leverage that would be gained upon the presentation of a petition to Parliament demanding, but with due deference, the immediate implementation of the Six Points.

The value of petitioning Parliament was hotly debated and the dispute between petitioners and those who reserved the right to resort to force was the cause of great friction at the First National Chartist Convention held in London at the beginning of February 1839.

Reliance upon a petition presented to a Parliament most of whose members were firmly set against it simply would not work and in a series of heated exchanges the veteran reformer Joshua Barnard compared it to ‘trying to hammer home a nail with a feather.’ It was a question that would continue to divide the Chartist leadership and vex its grassroots but while the advocates of Moral Force Chartism would not countenance insurrection the proponents of force were unable to provide a definitive course of action.

The Convention however did adopt a series of devices whereby their aims might be achieved should the petitioning of Parliament fail. For example, the withdrawal by its supporters of bank deposits thereby creating a run on the pound, the conversion of paper money into coin, and the possible implementation of the ‘Sacred Month,’ or General Strike.

But such ideas failed to fully satisfy either wing of the Movement; although, many of its most active supporters were from the middle-class it remained doubtful if their collective wealth was substantial enough to seriously threaten the economy and the more cynical among the Chartists doubted if they would in any case be willing to act against their own financial best interests. Likewise, Physical Force Chartists doubted that their poorer supporters could sustain a General Strike for any length of time, and why should they in any case be expected to carry the burden.

Moral Force Chartists also feared the mob no less than they did the Government and baulked at the idea of mobilising them for direct action, they were also frightened of the clampdown that would inevitably follow if they did so. But the argument for pricking the conscience of their betters simply rang hollow to many and lead Feargus O’Connor to respond scornfully:

“All the craft, all the artifice, all the ingenuity, all the courtesy of this Convention will not gain a single Member of the House”.

The divide within the Movement became explicit during the Convention and the situation was only worsened not improved by argument. George Harney, one of the more radical Chartists who would later turn to socialism plainly stated: "If this Convention simply does its duty, then the Charter can be won within a month.”

But what was this duty the mobilisation of the masses to intimidate the Government and the spilling of blood if necessary? If so, then it remained a frightening prospect to many.

In response Thomas Attwood, among others, demanded that the Convention repudiate without equivocation violence as a course of action and take a pledge of loyalty to the principles of peace, law, and order. No such pledge was made, and in the end few decisions taken as the Convention concluded no less divided than when it had begun.

Such was the intensity of hatred in the north to the blight of industrialisation, the factory system, and the Workhouse that no reconciliation seemed possible with the gradualist approach of their more reasonable southern counterparts.

In the summer of 1839, mass-demonstrations took place at Kersall Moor and Peep Green in the West Riding of Yorkshire where the atmosphere at both was so volatile that some Chartists were driven to question the responsibility of those who called such meetings. Even Feargus O’Connor’s own newspaper the Northern Star, the organ of Physical Force Chartism, felt inclined to counsel caution - there had been much reference to the Peterloo Massacre of twenty years earlier encouraging some to openly declare for armed insurrection.

For example, Harney and the black Londoner William Cuffay applauded the suggestion of forming a National Guard on the French model while Ernest Jones publicly prayed for the spark that would light the fire. Frightened and dismayed by the fierce rhetoric emanating from the north William Lovett felt obliged to speak out: “Instead of spending a pound on a useless musket I would prefer to see it spent on sending delegates out amongst the people. Indeed, any cry to arms without the support of the middle-classes can only end in misery, blood, and ruin."

Such remarks accurately reflected the views held by respectable artisans in the south who feared disturbance and the breakdown of order every bit as much as they desired change. Any resort to violence was an offence to their sense of decency and it was a view so often and so vehemently expressed that it drove Richard Marsden to request that in the coming conflict southern Chartists merely remain neutral.

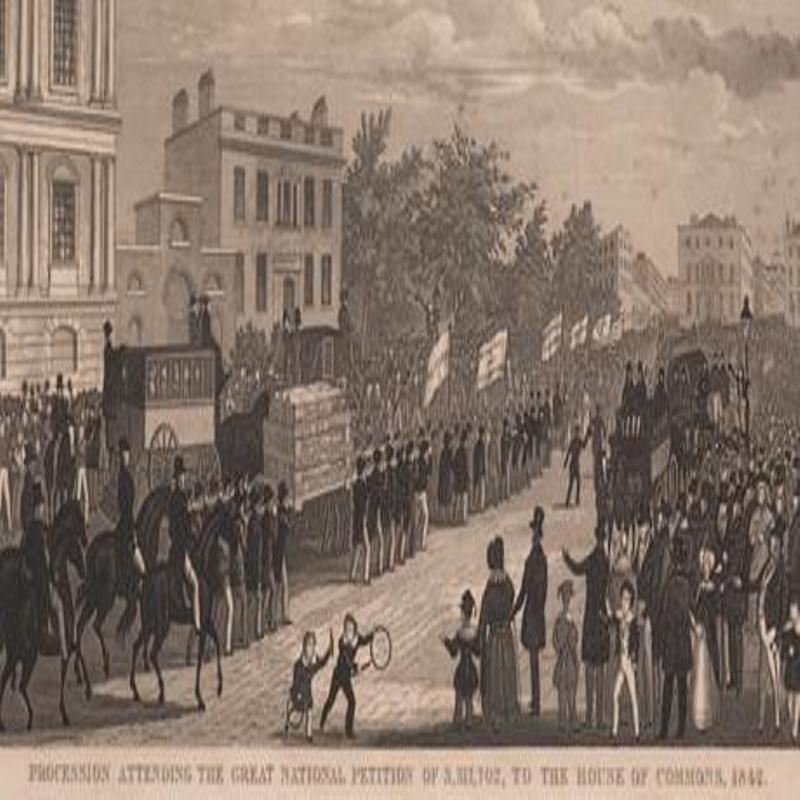

On 14 June 1839 to much fanfare and on a parchment three miles long the First Chartist Petition containing 1,280,000 signatures was presented to Parliament by Thomas Attwood who then tabled a motion in the House requesting the immediate implementation of the ‘People’s Charter’ and calling for its consideration, a motion that was overwhelmingly rejected by 235 votes to 46.

Great faith had been placed upon the presentation of the Petition, it had been passionately argued for and the wait and see attitude of its more vociferous advocates had served as a restraining influence upon those who sought more direct action, now it had been rejected out-of-hand just as the doubters had predicted it would be.

A year of campaigning and hard work had come to nothing and the descent into violence was the inevitable result as riots of varying scale and intensity occurred throughout the country the most serious being those that took place at the Bull Ring in Birmingham where troops had to be mobilised to disperse the crowd.

The riots had for the most part been a spontaneous response to the Petitions rejection and the uncoordinated smashing of windows and occasional house burning did not unduly concern the Authorities, but the threat of further violence had not diminished and what the Government most feared would indeed transpire, an armed insurrection.

On 4 November 1839, around 3,000 men, many of them coal miners armed with an array of weapons gathered outside the town of Newport in South Wales, their intention to march on the Westgate Hotel and free several of their fellow Chartists they believed were being held there under arrest. This was at least the pretext for an attack that had been under preparation ever since the rejection of the Petition five months earlier, as the military style operation itself would indicate.

The organiser of the uprising was John Frost, a disgruntled local dignitary and militant Chartist angry that his outspoken views had not only seen him replaced as Mayor of Newport but his license to serve as a local Magistrate revoked.

Tensions in the town had been high for some time and Frost’s personal grievances now added fuel to the fire. Split into three separate columns led by William Jones, Zephaniah Williams, and Frost himself they would march at night to avoid detection before converging on the Westgate Hotel simultaneously and taking its defenders by surprise. But things did not go according to plan, it was a foul night and stumbling about in the dark and the rain some got lost, many arrived late whilst others simply returned home. Worse still, they had not gone undetected and after taking into custody all the known Chartists in Newport the Mayor fortified the Westgate Hotel and with some 60 soldiers and several hundred Special Constables recruited from amongst the townspeople he prepared to defend it.

Frost and his men arrived outside the Westgate Hotel around dawn soaked to the skin and freezing cold but regardless of their condition he delayed taking action hoping the other columns would turn up and join them. When they did not he ordered the Hotel surrounded and at 09.30 banged on the door and demanded its surrender.

The response was a volley of musket fire from those inside which left 15 Chartists dead and many more wounded. Frost ordered his men to take cover and for those few with muskets to return fire but with little chance of breaching the defences after twenty-five minutes of sporadic fighting he ordered a withdrawal leaving behind 22 dead and 50 wounded. The defenders had suffered only 4 men lightly injured. As Frost’s men fled the town the other columns began to arrive, but it was too late.

In the ensuing days Frost, Jones, and Williams along with 200 others were arrested. They were later tried and sentenced to a traitor’s death but a petitioning campaign was to see their sentences commuted to transportation for life. Frost could consider himself fortunate and in 1856, when the threat posed by Chartism had long since passed, he was permitted to return to England and his hometown of Newport where he received something akin to a hero’s welcome.

If the more militant among the Chartists believed an armed uprising such as the one at Newport would spark a national insurrection, then they had been sorely disabused and the Government's apparent willingness to use the military and the full weight of the law to suppress any such disturbance served to cow many.

Just as the Sacred Month called the previous September had foundered on a lack of support and had been reduced to a three day stoppage it seemed that the belief in physical force had proven no less effective as a course of action than the unfounded faith that had been put in the value of morality by their more moderate brethren. Some now began to look towards an alliance with a campaign that had begun around the same time as the People’s Charter, was no less divisive, and drew similar crowds to its meetings - the Anti-Corn Law League.

The economic distress of the people had been exacerbated by the introduction of the Corn Laws which imposed upon the country by a landowning class that still dominated Parliament was intended to maintain profits following the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars by placing restrictions and high tariffs on imported grain, thereby keeping the price of bread artificially high whilst at the same time protecting the value of their land and the food it produced.

It was a law imposed with no thought for working people to whom bread was a staple diet or indeed employers who saw any restriction on free trade as an impediment to profit which kept wages low and unemployment high.

The Anti-Corn Law League founded by the Whig MP’s John Bright and Richard Cobden argued for the repeal of the Corn Laws on the grounds that it would guarantee the prosperity of the manufacturer by providing him an outlet for his products, it would relieve the England Question by cheapening the price of food and ensuring more regular employment, it would make agriculture more efficient by stimulating demand for its products, and it would through the promotion of free trade be a guarantor of greater peace in the world.

But there was to be no alliance of common objectives between the Chartists and the Anti-Corn Law League as a result of a mutual mistrust and deep antipathy that often verged on the paranoid for even though there were those amongst the more moderate Chartists who sought talks with the Anti-Corn Law League the radicals had little or no faith in the sincerity and goodwill of the very employers they blamed for their plight. Similarly, supporters of the Anti-Corn Law League would not countenance any deal with people they associated with machine wreckers and revolutionary Jacobins who would as soon see them hanged as sow their fields and spin their wool.

Together Chartism and the Anti-Corn Law League might have proved an unstoppable force for political and social change that it did not do so was the result of a failure of will on the one part and an act of deliberate sabotage on the other.

The rejection of the Petition in 1839 did little to dampen the enthusiasm of the Chartists and the continued economic recession ensured support remained high. On 4 May 1842, the MP Thomas Dunscombe presented to Parliament a Second Petition with 3,250,000 signatures and a series of demands that went way beyond the Six Points of the Charter itself declaring that action must be taken to curb the behaviour of the police, that working conditions in factories must be regulated, changes should be made to the Poor Law, punitive taxation of non-Conformists should cease, and it even dared to voice criticism of the young Queen Victoria.

The self-confidence of the Chartists proved to be misplaced however, and the Petition was rejected by 287 to 47 votes and gathered little support beyond those radical members already committed to it. Such an overwhelming rejection of the Second Petition was a bitter pill to swallow, as Feargus O’Connor’s Northern Star wrote with a mixture of resentment and despair:

Three and a half millions have quietly, orderly, soberly, peaceably but firmly asked that their rulers do justice, and their rulers have turned a deaf ear to that protest . . . the same class is to remain a slave class still. The mark and brand of inferiority is to be maintained. The people are not to be free.

With their hopes shattered once more many Chartists reacted angrily taking to the streets, stoning the houses of employers, and confronting the forces of law and order. While a series of strikes that had begun in the factories and foundries of the West Midlands soon spread to the Cotton Mills of Lancashire and as far north as Scotland.

In some factories departing workers sabotaged the machinery removing boiler plugs from steam engines ensuring production was brought to a halt and earning the strikes their name as the Plug Riots. But the reaction to the Petitions rejection was for the most part spontaneous and the demand from Harney among others for co-ordinating action and holding mass-demonstrations throughout the country in support went unheeded.

Feargus O’Connor, for example, did not even believe that the strikes were genuine and had been deliberately engineered by the factory owners and supporters of the Ant-Corn Law League to discredit the Chartist Movement.

The Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel was inclined to let the disturbances run their course but others in his Cabinet disagreed. The Home Secretary Sir James Graham wrote:

My time has been occupied with odious business arising from the mad insurrection of the working classes. I believe that only force alone can subdue this rebellious spirit.

Under pressure he despatched troops to restore order.

By the end of August, the trouble for the most part had dissipated but the clampdown that followed was no less harsh for that with more than 1,500 Chartists arrested, among them Harney and O’Connor, and 79 transported for life.

The enthusiasm for Chartism had always waxed and waned according to the prevailing economic conditions and the outright rejection of the 1842 Petition followed by a period of relative calm in the markets saw support for the Chartists go into a sharp decline. Events also lead to control of the Movement being effectively wrested from the hands of the moderates by the Physical Force Chartists and their de-facto leader Feargus O’Connor which saw many abandon the campaign altogether including Thomas Attwood (William Lovett had long-since departed).

The hero of the radicals Feargus O’Connor had been born in County Cork, Ireland, where he was raised in the rough-and-tumble world of Irish politics where a man who could neither speak his mind nor use his fists was not worthy of respect. Despite being a Protestant after studying law at Trinity College, Dublin, he campaigned hard for Catholic Emancipation becoming an ardent supporter of its leader Daniel O’Connell from who he learned much about the strategy required for a successful political campaign.

He was elected twice as the Member of Parliament for Cork but was eventually disqualified from taking his seat because he did not meet the property qualification required to do so, though in truth he had secreted away his fortune and wasn’t about to tell anyone where it was. In any case, as a radical by nature and a fiery orator who knew how to manipulate a crowd and enjoyed doing so, parliamentary procedure bored him.

In 1837, he founded the radical newspaper Northern Star becoming in the same year the Representative for the London Working Men’s Association in Leeds. He endorsed the People’s Charter but not its London leadership believing as they evidently did not in the immediacy of action and was confident that it was, he and not the erudite autodidacts of the capital city who would win the hearts and minds of the people.

His enthusiasm for leading the Movement had not been dampened by the eighteen months he served in prison following the Newport Rising in which though he did not participate he was almost certainly aware of. Yet for all his self-confidence and aggressive rhetoric his words would often be couched in ambivalence with a call to arms followed by cautious paragraphs of peace.

In the intimidation of numbers, blood curdling phrases, and the threat of insurrection lay the prospect of success and so whilst he was unequivocal in his denunciation of police violence he turned a blind-eye to those Chartists who attacked and broke up Anti-Corn Law League meetings.

Following the 1842 debacle however, and the failure of Chartism to transform the political landscape he adopted a more grassroots approach. In 1845, he founded the Chartist Co-Operative Land Company - its aim to purchase agricultural land and parcel and it up into small-holdings which would then be provided to subscribers at an affordable rent thereby encouraging workers to abandon the cities and return to the land.

But the change of emphasis did not see Chartism disappear from the political scene and it remained vocal throughout the 1840’s but its prospects of success appeared slim, and support diminished accordingly. As such its tactics changed, the Sacred Month was abandoned and armed insurrection was rarely spoken of, instead Chartists campaigned in elections for those who did not possess the vote to highlight the iniquities of the system.

Enthusiastic support for Chartist candidates on the hustings and the surprise election in 1847 of Feargus O’Connor as the MP for Nottingham convinced many that the time was right for one last push for victory - a new Petition, the greatest of them all, with a mass-rally in London to accompany it followed by a march on Parliament. Others however poured scorn on the idea - it had not succeeded before so why should it succeed now? But it was to be given impetus by events elsewhere.

The political climate in 1848 was to prove very different from previous years as revolution swept across Europe; the French Monarchy had fallen, the Austrian Emperor had been forced to flee, Italy was in turmoil, Hungary had risen in revolt and Liberal Parliaments had been established in many German States. The entire European Continent quivered and shook under the demands of the people, and it seemed as if the established order was about to be swept into the dustbin of history. How could Britain possibly remain immune?

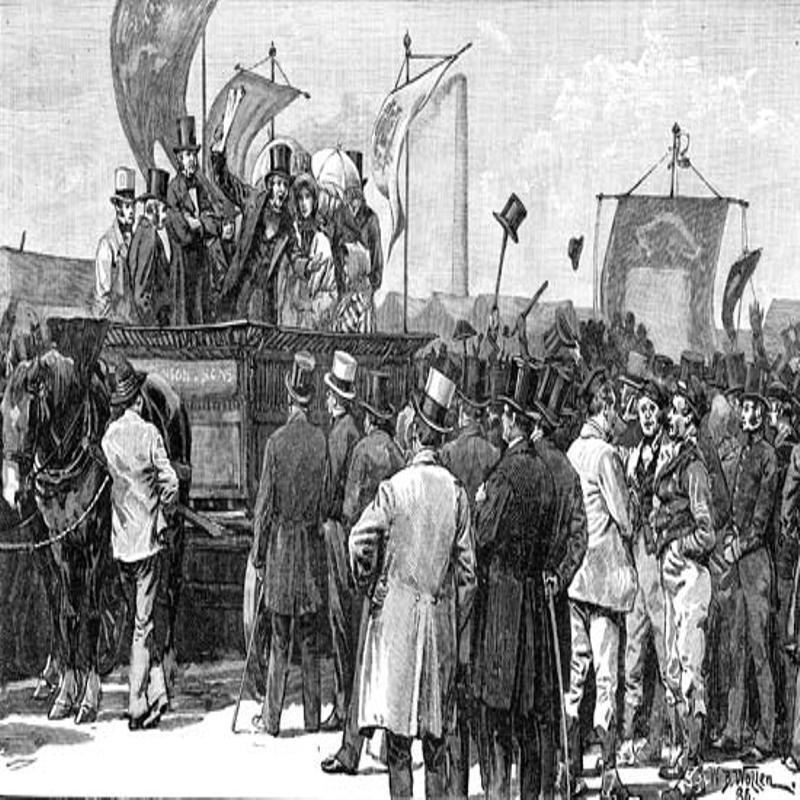

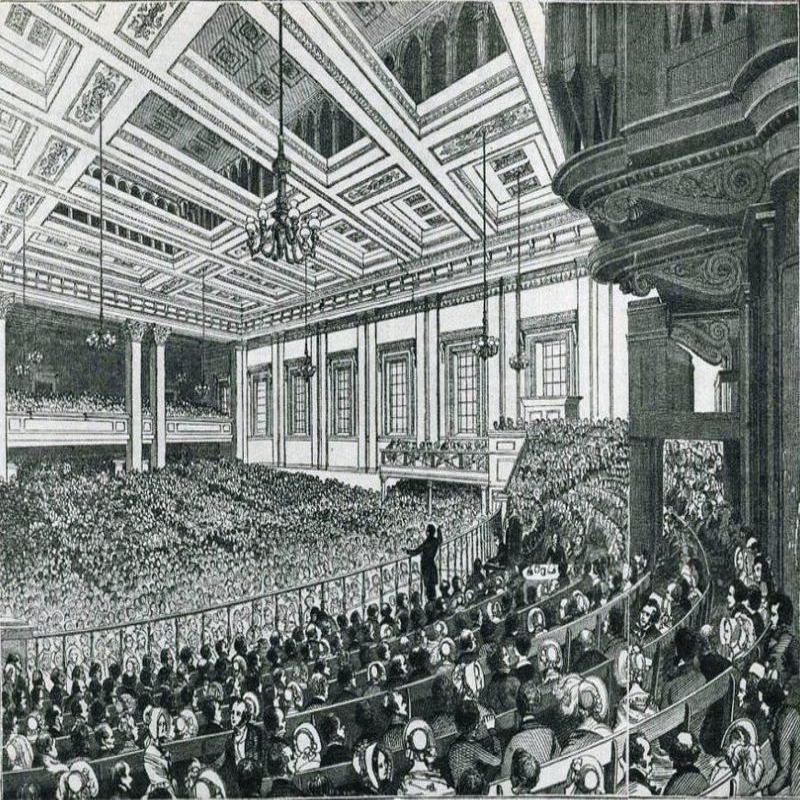

On 10 April 1848, as many as 200,000 Chartist supporters gathered on Kennington Common for the march on Parliament and the delivery of the Third Petition.

Although, the meeting on the common was never intended to be anything but peaceful the reputation of the firebrand O’Connor went before him, and the Authorities had used the time between its announcement and the demonstration itself well. The army had been mobilised and placed under the command of the aged Duke of Wellington, buildings such as the British Museum and other London landmarks had been fortified, the bridges across the River Thames were covered by cannon, and as many as 100,000 Special Constables had been recruited among them the novelist Charles Dickens and the future Emperor Napoleon III of France

O’Connor, who intended to place himself at the head of the grand procession that would march on Parliament, a visual and unmistakable statement of the will of the people, was instead told in no uncertain terms that if the crowd did not disperse the Riot Act would be read and that any attempt to cross the bridges over the Thames would see the marchers fired upon. This then was the moment and O’Connor whose fiery rhetoric had not always matched his actions faced a terrible dilemma, to back down now in the face of such intimidation would be a humiliation from which Chartism would assuredly never recover but the demonstrators though great in number were unarmed and unprepared for confrontation, indeed, many had brought long their families.

The atmosphere was relaxed one, not one of anger; picnic hampers and pork pies not cudgels and staves were the order of the day. Even so, there were a significant number of hardliners who wanted to test the will of the Government to fire upon its own people. But O’Connor was not one of them. He did not doubt the resolve of the curmudgeonly old Iron Duke whose contempt for the common man was barely disguised to do anything required to keep them firmly in their place.

Having negotiated the right for himself and a small number of other Chartists to proceed to Parliament and present the Petition he ordered the crowd to disperse and go home, by doing so he almost certainly prevented a bloodbath.

The Chartists claimed to have a Petition with 5.75 million signatures or 1 in 6 of the entire population but the recorders for the Committee of Public Petitions stated that there were only 1.3 million many of which were of dubious origin, though O’Connor doubted their claim to have counted them at all given the short period of time between receiving the Petition and their announcement.

Shortly afterwards many of the names that appeared on the Petition were published, some it was noticed had merely made a mark whilst others included pig face, pug nose, mouse, the name of the Prime Minister, numerous Queen Victoria’s and even the grand old Duke of Wellington himself.

The Chartists had been held up to public ridicule and the damage was immense.

When the House of Commons at last came to debate the Petition more than a year later only 15 MP’s supported O’Connor’s motion and although, it was to linger on for a further ten years Chartism was never again a significant force in British politics.

With the Third Petition scorned, the financial structure of his Land Plan declared illegal, the Northern Star’s circulation in steady decline, his reputation impugned, deserted by his friends, and close to bankruptcy, Feargus O’Connor took to drink for solace. Indeed, his family began to fear for his mental health.

In 1852, he physically attacked three of his fellow MPs in separate incidents on the same day and had to be restrained by the Serjeant-at-Arms. Not long after to pre-empt a possible prison sentence his sister had him admitted to a Lunatic Asylum. He was later released back into his sisters care but never truly recovered from his mental breakdown and died soon after on 30 August 1855, aged 61.

Despite his apparent loss of nerve at Kennington Common for which he was never forgiven by many Chartists, there remained a great deal of affection amongst the people for a man they considered one of their own and more than 40,000 mourners followed his cortege through the streets of London.

In summation, the stark differences of approach between Moral and Physical Force Chartists prevented it from ever becoming a coherent national movement. At no point did it have a settled chain of command or an agreed upon strategy and the fact that the divide was split north and south, between industrial and rural Britain, hampered even further the possibility of a unified campaign for change.

Although the Charter itself was all-embracing and endorsed by the Movement it could not alone compensate for the regional and tactical variations that were tearing it apart thereby stripping it of any co-ordinated purpose. Shared aims and common purpose could not bridge the gap between reform, upheaval, and the best means by which to obtain either.

It proved impossible to develop a platform of common interest based upon the Six Points alone without considering economic/social variation and changed circumstance.

Chartism also remained largely opposed by the middle-class who were rapidly evolving into the most influential and significant sector of society.

As we have seen an attempt was made to forge an alliance with the Anti-Corn Law League, but this foundered for the most part on the intolerance of the Physical Force Chartists who aggressively resisted any such move, and it was their hostility that alienated many who might otherwise have been their natural allies. In doing so they deprived the Movement of an invaluable source of funding and access to those in Government who could direct policy. The fact that the Corn Laws were repealed in June 1846, despite intense resistance that split the Tory Party apart and effectively ended the political career of Sir Robert Peel provided very real evidence of this.

Some of the Chartists more radical schemes also served to alienate sectors of the working class and none more so than Feargus O’Connor’s Land Plan that sought to reverse the course of the Industrial Revolution. It was a plan fiercely opposed by the incipient socialist movement who looked to the example of the reformist factory owner Robert Owen for inspiration, and the early trade unions who sought shorter hours, higher wages, and improved working conditions for their members not to deprive them of their employment. After all, it had been the vagaries of the harvest, the uncertainty of and poor return for their labour, and the constant threat of starvation that drove them from the land in the first place.

As a result of all these factors it can appear in hindsight that the People’s Charter was doomed to fail from the outset yet its demands far from being utopian, or indeed revolutionary were sound both in essence and practicability. Indeed, they were essential in the development of a properly functioning and mature democracy with, in the following decades all but one of its Six Points becoming law, the removal of the Property.

Qualification for sitting Members of Parliament occurred in 1858, the Secret Ballot Act was passed in 1872, the Redistribution of Seats Act of 1885 created equal constituencies, the payment of MP’s became reality following the Parliament Act of 1911, and Universal Male Suffrage along with restricted Female Suffrage became law with the passage of the Representation of the People’s Act of 1918 (women would receive the vote on equal terms with men ten years later).

Of the Charter’s original Six Points only the demand for annual elections remains yet unfulfilled.

Tagged as: Victorian

Share this post: