The Commune: Paris in Flames

Posted on 31st August 2021

On 19 July 1870, after months of increasing diplomatic tension over the proposed candidate for the vacant throne of Spain, the Emperor Louis Napoleon III of France declared war on Prussia.

He had fallen into the trap carefully prepared for him by the Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck who had been seeking the unification of Germany under Prussian hegemony but knew that this could only be achieved by emasculating a French State that would never tolerate such a permanent threat to its Eastern border, so cleverly manipulated French national hubris and exploited the Emperor's own Napoleonic pretensions to doctor the infamous Ems Telegram to make it appear that its wording was a slur on French honour.

The advance was checked at Mars-le-Tour but the following day when the two armies clashed again at Gravelotte the Prussian attack was repulsed with heavy casualties. Exhausted and spent, they nervously awaited a French counterattack which never came. Inexplicably, Bazaine had withdrawn his forces into the nearby fortress town of Metz where they were immediately surrounded and besieged. A resounding French victory had been turned into an ignominious defeat.

Learning of the perilous situation Bazaine now found himself in Louis Napoleon determined to come to his relief and personally accompanied the army of Marshal Patrice MacMahon as it marched on Metz and straight into a trap.

Encircled by a pincer movement the French army was forced to take shelter in the city of Sedan where despite repeated and increasingly desperate attempts to break the encirclement that were to cost 17,000 lives the Emperor and MacMahon were forced to surrender along with 83,000 of the best troops in the French army.

With one army defeated, another besieged, and the Emperor safely under lock and key and following a meeting with Bismarck forced to abdicate, it seemed after just 6 weeks the war was as good as over.

Yet outraged by the humiliation foisted on them by their blundering Emperor the French refused to surrender.

On 4 September, the Monarchy was abolished, and a Republic proclaimed while in Paris a Government of National Defence was formed under General Louis Trochu. Two days later Jules Favre announced on behalf of the Government that France “will not yield an inch of its territory nor a stone of its fortresses.” Meanwhile, spurred on by the radical politician Leon Gambetta new armies were hastily formed in the provinces - the war would continue. But there was nothing to prevent the Prussian Army from marching on Paris and by 19 September it was surrounded and besieged. The defences of Paris were strong however, and the city well garrisoned with 160,000 regular troops reinforced by 200,000 National Guardsmen.

The National Guard was a militia of Paris citizens which elected its own Officers and owed its allegiance largely to the arrondisement in which it was formed often refusing to fight elsewhere. Its loyalty then was uncertain with many National Guard Units from the working-class districts electing radicals, socialists and even anarchists to lead them and they were regularly accused of being ill-disciplined and truculent, of deserting their posts, and even of being drunk. Nobody could be sure where their animus lay and many of the Parisian bourgeois feared them more than they did the Prussians.

Paris had remained a hotbed of radical politics ever since the Revolution of 1789 and just 22 years earlier King Louis Philippe had been overthrown following street demonstrations and the Second Republic proclaimed. The mere removal of a King and hollow declarations of liberty were not enough however, and the demonstrations continued with the demand that grievances be addressed. Having refused to disperse they manned the barricades determined to resist any attempt to make them do so.

The Government responded with force and in the street-fighting that followed thousands of ordinary Parisians were killed as the army re-took the working-class districts of the city.

Those politicians who had ordered the troops to fire on their own people during those bloody June days were still in positions of power in 1870 and the legacy of bitterness and resentment that had accrued had never gone away.

Having defeated the enemy in the field Prussian policy was to minimise casualties and not to assault Paris but keep it bottled up and starve it into submission.

The Parisians were no less were determined to resist and they had been promised by the ambitious young politician and Minister of the Interior Leon Gambetta that France would come to their rescue.

In October, he had staged a daring escape from the city by hot air balloon and began raising the armies he had promised and in a wave of patriotic fervour in no time mobilised 500,000 men but these were for the most part raw recruits and there was no time to train them; courage, determination and national pride then, would have to overcome a lack of discipline and battlefield awareness - they were not able to do so.

Despite an early victory at Coulmiers on 9 November, and another at Orleans, a series of defeats swiftly followed at Amiens, Bapaume, Le Mans and St Quentin. Despite their best efforts they were unable to advance upon and relieve Paris. Similar attempts to break out from the city also failed.

In the meantime, the people of Paris were starving, cats, dogs and rats became the staple diet of poor Parisians and even the Zoo's two elephants had been eaten. With what was left of the city's food supplies having been put aside to sustain the troops people quite literally began to die of hunger on the streets of the city.

The Prussians however had been rattled by the determination of the French to liberate their capital and frustrated by the bloody-minded refusal of the Parisians themselves to surrender. In response, the decision was made to bombard the city in preparation for a possible assault and giant howitzers were brought from Germany to do the job. If the Parisians would not succumb to starvation, then they would be blown to Kingdom Come.

On 25 January 1871, the bombardment began and that same day General Trochu in command of the garrison and Jules Favre the leading politician in the city began armistice negotiations with the Prussians. Three days later, Paris surrendered.

Despite all the hardships and privations, they had endured the working people of Paris were not so much relieved that the siege had come to an end but outraged. It was they after all who had borne the brunt of the siege, it was their son’s and their brothers who had died on the fortifications. Yet as soon as the wealthier arrondisements had come under bombardment the Government had meekly surrendered. They had not been defeated by the Prussians but betrayed by their Generals, by their politicians, and by their own bourgeoisie.

Leon Gambetta, in Tours, was furious upon hearing of the news and immediately ordered an attack upon the Prussian forces around Orleans, but again it was easily repulsed. With the fall of Paris, the French spirit of resistance had been broken and following Gambetta’s resignation on 6 February hostilities effectively ceased.

The Franco-Prussian War had lasted seven months and was a humiliation for France with more than 138,000 of their soldiers been killed (along with 45,000 Prussians) and many more captured. The siege of Paris had also been costly with 24,000 military casualties and a further 47,000 civilians dying of starvation and disease.

The Prussians would go on to impose humiliating peace terms that would include the loss of Alsace-Lorraine and a huge indemnity. But the war at least was over, or so it seemed.

Following the cessation of hostilities, the Prussians permitted National Elections to be held so that a legitimate Government could be formed to negotiate the peace treaty and sign it into law.

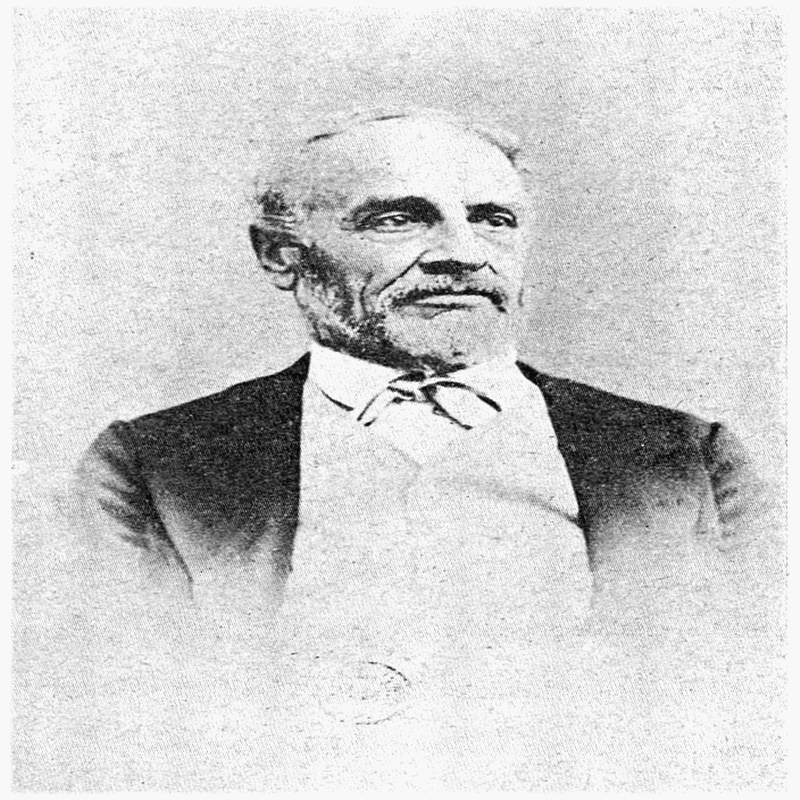

On 17 February, the hard-line conservative Adolphe Thiers was elected head of the new Provisional Government. He had been against the war from the start and had counselled Louis Napoleon not to enter upon it but then he was less interested in the Prussians than he was in suppressing those he considered the enemy within. The same day that Thiers was elected Interim President of France the Prussians held a victory parade through the streets of Paris.

The atmosphere in the city was tense and the few people who turned out to watch the Prussian Army parade down the Champs Elysses did so in grim silence. Many had stayed away not just out of disgust for the enemy but for fear of violence as no serious effort had been made to disarm the 200,000 National Guardsmen and there was a great sense of unease.

The parade was to pass off without incident, but it was evident that Paris remained a powder keg and the Prussians did not remain long. In the days following the National Guard spirited away more than 400 cannon which had been left in various parks throughout the working-class districts.

Paris was a Red City in a largely conservative country, and it most certainly had not voted for Adolphe Thiers or the Royalist majority that now sat in the National Assembly. They expected trouble and they would be ready when it came. Thiers likewise expected trouble and was determined to pre-empt it or at least reduce the National Guards capacity to cause it. The Prussians had also made it plain that if Thiers did not disarm the National Guard, then they would do so. He needed little encouragement.

On 18 March, he ordered troops of the Regular Army to seize the guns at Montmartre.

As the night began to draw in the troops nervously advanced on Montmartre hoping that the lateness of the hour would see their path clear of any possible resistance. They were disheartened then, to see so many civilians and armed Guardsmen on the streets to greet them. The mood was good however, and there was little animosity as troops fraternised with the crowd and exchanged barbs. But the shout soon went up that they were there to seize the guns and the mood darkened once more. The crowd now began to close in and there was a great deal of jostling and the light-hearted banter had changed to verbal abuse.

Fearing that he could not guarantee the loyalty of his own men General Claude Lecomte ordered his troops to disperse the crowd before the situation spiralled out of control, but he was too late. Scuffles had already broken out and panicking he ordered his men to open fire on the crowd, but they refused. Three times he repeated the order and three times they were ignored.

Charging up and down the line waving his sword and verbally chastising his men he was eventually dragged from his horse and taken prisoner along with his second-in-command General Jacques Thomas.

Lecomte was well-remembered as a former Commander of the National Guard and hated for being a class traitor. Later that night both he and Thomas were placed before a wall and shot.

Fearing revolution and believing that troops within the city were preparing to mutiny, Thiers ordered all Government officials to leave Paris immediately and make for Versailles with himself in the vanguard. The army also withdrew soon after - the City of Lights once more belonged to the radicals.

Karl Marx was to describe Thiers as “a man who had charmed the bourgeoisie by being the most consummate expression of their own class corruption.”

It was a damning indictment but not one without foundation for he had risen, high on the fears and prejudices of others, and his response to the Paris Commune was to be motivated as much by personal enmity as it was patriotism. His hatred of the mob was absolute and of those who to presumed to represent them.

On 26 March, the Central Committee of the National Guard which had been the effective rulers of Paris since the Government had abandoned the city a week earlier held city-wide elections. As only 220,000 of the 485,000 registered voters turned out to cast their ballot, Thiers immediately declared the elections invalid before the results were even known.

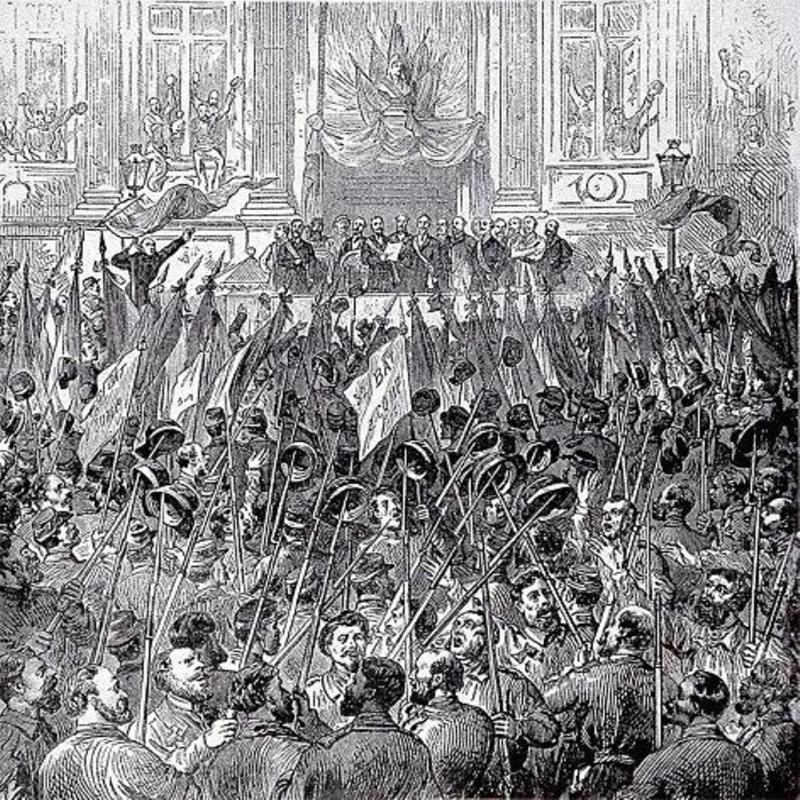

Two Days later following a parade and march past by the National Guard the Commune was declared from the steps of a Hotel de Ville adorned with Red Flags and before an enthusiastic crowd of thousands.

The 92 strong Communal Council elected was overwhelmingly radical in its makeup and its membership covered the entire spectrum of left-wing politics something which would normally be a recipe for strife and it was indeed a divided body; but the one thing they could all unite on was the need to have the veteran insurrectionist Louis Blanqui to lead them.

Thiers had expected that the Radicals would look to Blanqui for leadership and so on 17 March he’d had him arrested and taken to Versailles. In response, the Commune passed the Law of Hostages and placed several prominent citizens including city's Archbishop, Monsignor Darboy in confinement hoping to use them as a bargaining chip for the release of Blanqui. But Thiers refusing to recognise the legitimacy of the Commune would not negotiate with them. When a delegation of Paris's leading Freemasons travelled to Versailles in an attempt to do so and end the impasse, Thiers informed them curtly: "If you represent the Commune I shall not talk to you.” The remit of the Government he insisted would run in Paris as it did elsewhere in the country. On this there could be no compromise.

With no one man to lead them the work of the Commune, as the name implies, would be a collective effort and they set about their work with gusto and in short order it passed laws for the separation of Church and State, the ending of night-time work, the remission of rents, the abolition of interest on commercial loans the, free return of goods pawned during the siege and the granting of pensions to war widows. They also permitted the partial takeover of factories.

But as radical as the Commune appeared it stopped short of nationalising the financial institutions and when it needed the money to pay for their reforms it instead went cap in hand to the Bank of Paris just like anyone else.

As the weeks passed the Commune was to veer even further to the left. Its official symbol would be the banner of the World Republic and the tricolour that flew over the Arc de Triomphe was replaced with the Red Flag. On 5 April, the hated guillotine, that symbol of State repression, was publicly burned.

The leadership of the Commune was a mixed bag of the Radical Left some of whom were true believers, others less so.

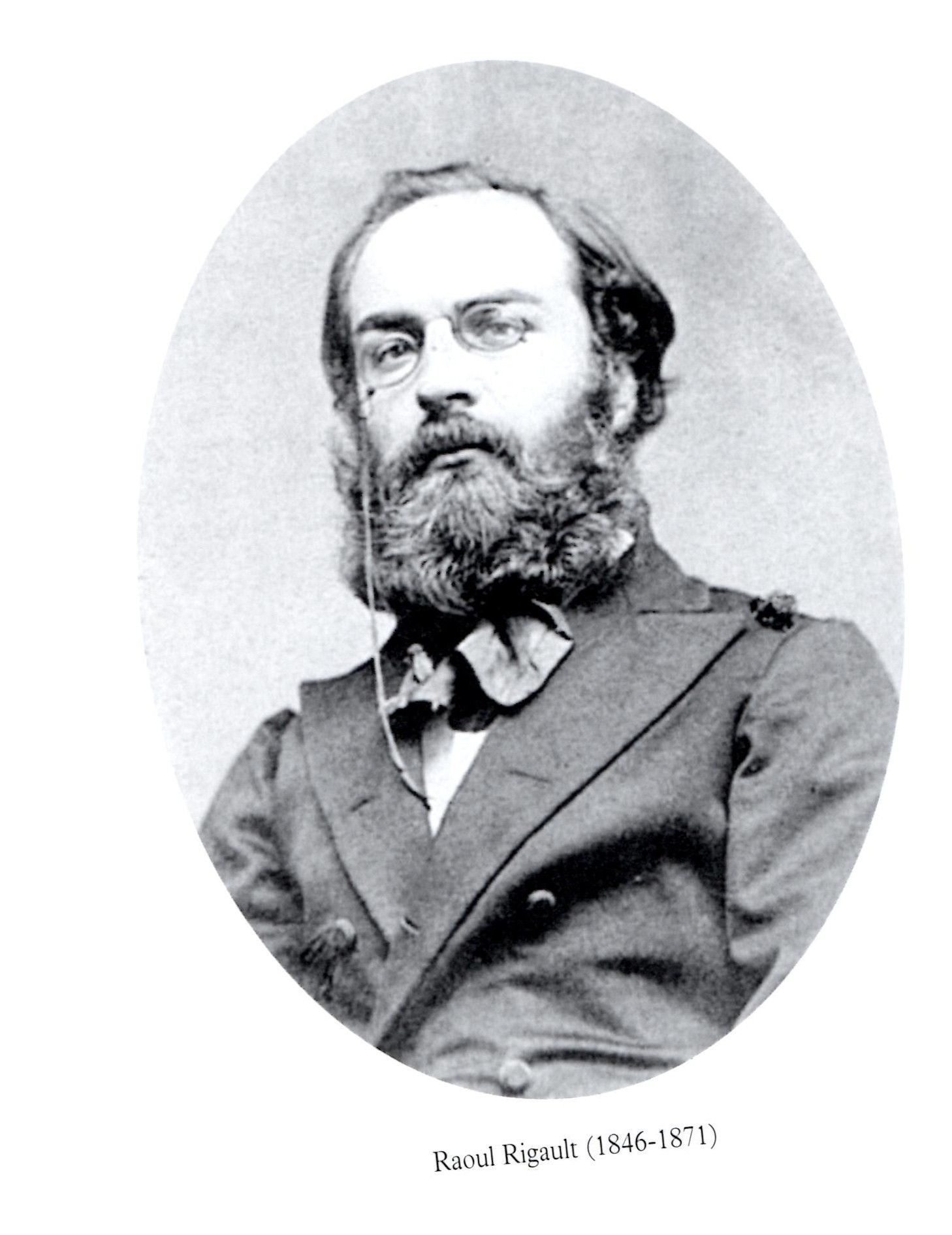

Raoul Rigault, the anti-clerical and bohemian avenger of the people; Felix Pyat, the smooth talking journalist and playwright whose convictions were to prove as fictional as his characters; Theophile Ferre, the radical agitator, cold-bloodied assassin and lover of Louise Michel; Gustave Flourens, the flashily gallant knight of his own imagination; Louise Michel, the feminist socialist and Red Virgin of Montmartre; Eugene Varlin, the socialist bookbinder and trade union activist; Louis Charles Delescluze, the consumptive always dignified journalist and long-time critic of the regime. All would play a significant role in the life and death of the Commune.

Despite the presence of the French Army just a few miles away at Versailles and the obstinate refusal of Thiers to compromise, confidence among the Communards remained high. But the forces at Thiers disposal were growing all the time as the Prussians who still invested the city released prisoners-of-war to his army.

To prevent the Versailles Army from becoming too powerful the Communards decided, in the spirit of 1789, to make a mass-sortie from Paris and destroy it while they still could.

They believed that the soldiers at Versailles, conscripts and fellow workers after all, would not oppose them but these were mostly men from the regions, peasants who had long desired to avenge themselves on the Reds of Paris for the iniquities of the French Revolution a hundred years before.

On 3 April, 27,000 National Guardsmen advanced from the city full of bravado, their full-throated cheers ringing the air. They were led by General Jules Bergeret and Gustave Flourens.

Bergeret was excitable and brave and had a reputation for strategic competence that was not to be borne out by events.

Flourens, tall, slender and balding with his gold-braided waistcoat and Turkish scimitar had panache and elan but he was little respected by his men who thought him quite effeminate, so much so that they had nicknamed him, Florence. He had earlier assured the Council that victory was certain but as the guns at Versailles roared and the first shells began to fall amongst the Guardsmen they began to waver. They were not regular soldiers, some had only been recruited in the days immediately before the advance, and few had been under fire before. As the shelling intensified many broke and fled back towards the city.

Bergeret did what he could to rally his men and with the 3,000 or so he had remaining to him he continued the advance but eventually had little choice but to order a general retreat. Nothing was going to stop Flourens, however. He considered himself a man of action and his blood boiled, he said, with the urge to come to grips with the enemy. On he went until finally he reached the village of Reuil accompanied by just one man. Retiring to an Inn for the night he fell fast asleep, but the Authorities at Versailles had been informed of his presence.

He woke the following morning to find the Inn surrounded by troops but had little time to react before they burst through the door. Shots were exchanged, Flourens comrade was mortally wounded in the short fire- fight before he was himself overpowered and dragged into the courtyard where an Officer of the Versailles Army shot him dead - he was the first leading Communard to be killed.

The fiasco of the attack on Versailles came as a terrible shock to the Council, the myth of the irresistible sortie on-masse had been shattered Paranoia set in as they believed they must have been betrayed and Bergeret was temporarily placed under arrest. A Committee of Public Safety like that used during the Terror was now established to root out suspects and traitors.

Trying to take advantage of the disarray he believed had infected Communard ranks, Thiers ordered an attack upon Paris, but its defences were still formidable, and the attack was bloodily repulsed. Meanwhile, the business of the first Workers' Government in history continued.

Legislation was passed, though most would never be implemented, new recruits were still joining the National Guard and there was a flourishing women's movement. Indeed, women were to play a prominent role in the life of the Commune.

Nathalie Lemel and Elisabeth Dmitrieff founded the Women's Union for the Defence of Paris, cared for those injured in the fighting and established cooperative restaurants to feed the poor. Paule Minck ran free schools whilst Anne Jacland founded and edited the radical newspaper La Sociale.

Louise Michel organised and armed her own Women's Battalion and both she and Jacland were also members of the Vigilance Committee responsible for hunting down and punishing suspected traitors. All these women were to fight on the barricades.

In Versailles, the pressure was beginning to build on Thiers. The Prussians were becoming impatient at his failure to bring the Commune to heel and Bismarck told him that if he did not do so he would consider his government extinct and pound Paris to rubble.

Thiers believed this would be a disaster for France and would lead to the occupation of the entire country. But despite by now having 200,000 troops under his command he was unable to break through the city's defences, which had after all resisted the Prussian Army for five months. In his desperation he took to trying to bribe someone to open one of the gates for him but there were no takers. In the meantime, the Commune had utilised the military talent it had at its disposal: Gustave Cluseret, a highly decorated veteran of the American Civil War whose military genius did not perhaps match his ego busied himself reviewing the fortifications and ensuring that all possible avenues of advance into the city were covered.

Jaroslaw Dambrowski, the exiled Polish mercenary and the Communes best General had been instilling discipline into the troops. He could also call upon the experience of the professional soldier Walery Wroblewski and the firebrand, Paul Brunel.

The Versailles Army had recently been provided with heavy howitzers by the Prussians which they now used to bombard the fortifications at the Pont-du-Jour. Still, they could not make the breakthrough and a direct assault on the city was ruled out as being potentially too costly in loss of life and therefore damaging to morale.

On Sunday, 21 May, a civil engineer named Ducatel, no friend of the Commune that’s for sure, was strolling near the fortifications in the west of the city when he noticed that they were deserted not only that but one of the gates had been left open. Scaling the ramparts, he improvised a white flag and began to wave it wildly at the Versailles troops nearby.

Eventually, an Officer cautiously approached to be told by the excited Ducatel that the fortifications had been abandoned and that they could walk straight in. Surely it was too good to be true, it must be a trap, but amazingly it was true. The Communards to avoid the bombardment had withdrawn to a safer distance.

The breach had been made and ‘Le Samaine Sanglante’ or ‘The Bloody Week’ was about to begin.

Troops of the Versailles Army under the command of General Felix Douay were soon flooding through the open gates at Pont-du-Jour and Pont-St-Cloud. The Council of the Commune, which was in session at the time and for the last time as it transpired, greeted the news of the breakthrough in stunned silence.

Once they had recovered from the initial shock the order was given for barricades to be erected throughout the city and a general command to arms was issued.

Paul Brunel was given command of the strategically important Place de la Concorde, but no order was given to counterattack in the area where the breakthrough had been reported. In the meantime, the Versailles troops were making rapid progress through the prosperous and welcoming suburbs of Paris.

Jaroslaw Dombrowski tried to stem the tide of the advance but many of his men had already fled in panic. Still, he did his best with what he had while urgently begging Charles Delescluze, the Minister of War, for reinforcements. But he knew he could not hope to halt the advance only slow it down a little whilst preparations were made for stiffer resistance elsewhere.

By nightfall more than 70,000 Versailles soldiers were on the streets of Paris and the following day they took the Trocadero and were advancing on the Place de la Concorde.

Here however they received their first setback, caught in a murderous crossfire they were repulsed with heavy losses and forced to retreat. The urban topography of Paris now worked against the Communards, however. The wide boulevards that had been built by Baron Haussmann at the request of the Emperor Louis Napoleon III for the specific reason of negating the use of barricades at a time of revolution now came into effect with many of them rendered useless by flanking movements. As a result, despite his victory, Brunel was forced to withdraw. As he did so he ordered any buildings that might afford the enemy cover set alight.

The rumour spread that the Communards had unleashed 8,000 female petroleuse on the city not only to burn it down but firebomb the troops as they passed by. No such order had been given but the rumour was to cost a great many women their lives as those found on the street were beaten or bayoneted to death.

The fires that had been set soon took hold and as Paris blazed the flames lit up the night sky for miles around.

Raoul Rigault, the Minister of Police seemed less interested in the military situation than he was in an act of personal vengeance. He had long blamed one of the hostages, Gustave Chaudey, for the death of his friend Sapia who had been shot during a demonstration outside the Hotel de Ville. Arriving at the Saint-Pelagie Prison he ordered that Chaudey be brought before him where he was told he was to be shot. When Chauday pleaded that he had a wife and a child, Rigault replied that he couldn't care less, and that anyway the “Commune will take better care of them than you would.”

A defiant Chauday stood before those who were to execute him and shouted "Vive le Republique!" The firing squad reluctant to commit murder only wounded Chauday and so Rigault finished the job himself. He then ordered the arbitrary execution of several other hostages before resigning his post as Minister of Police and disappearing.

His replacement, Theophile Ferre who had long been advocating the execution of the hostages now determined to do so.

The forty-eight hours since the initial breakthrough had been a disaster for the Commune with their response uncoordinated, many of the National Guardsmen who had fled when the attack began not returning, and the response from those who remained lacklustre. But as they were forced back towards the working class east of the city their resolve returned, and their resistance stiffened. Soon they would be fighting for their homes and their families, and they were to do so with great courage.

Louise Michel, with 25 of her Women's Battalion had been retreating down the Boulevard de Clichy fighting from barricade to barricade along with Elisabeth Dmitrieff who had been ordered to set fire to the Butte de Montmartre. Before she could do so she ran into Dombrowski who curtly informed her that to do so was pointless, all was lost, and that she and the others should save themselves. Moments later he was shot and mortally wounded.

In the meantime, Michel with only ten of her women remaining and cut-off from her intended destination made for Belleville where she joined up with the rest of her Battalion. There they made their stand. A British observer would write: "They fought like devils, much better than the men, and I had the pain of seeing fifty shot down after they had been surrounded and disarmed."

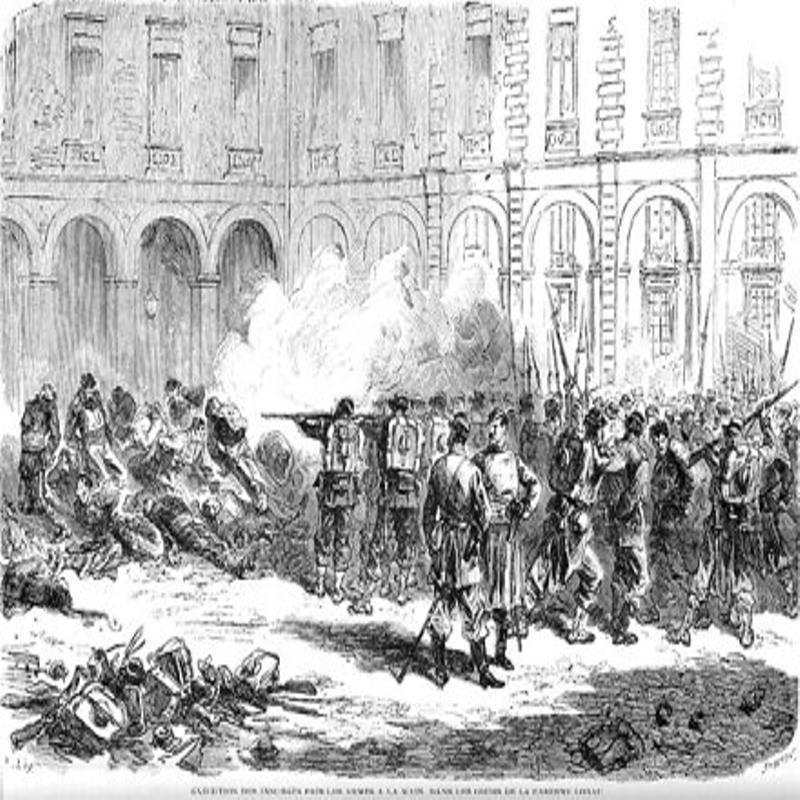

Atrocities were now occurring throughout the city.

At a Field Hospital near St Sulpice more than 80 wounded Communards and those tending to them were bayoneted to death. Twenty-five women who had poured boiling water over soldiers as they passed beneath their windows were dragged from their homes and shot. Any Communard captured in uniform was likely to be executed on the spot but then no mercy was shown to the Versailles troops either.

In revenge for atrocities committed elsewhere, Theophile Ferre ordered the execution of all the remaining hostages. This was something he had wanted to do all along and in his orders, he added the postscript, underlined - especially the Archbishop.

Again, the firing squad went about their business with little enthusiasm and though the ailing and elderly Archbishop Darboy and 8 others were shot there was no desire to kill any more and the remaining hostages were permitted to escape.

Paris was by now a city at bay, its defence would be a outrance and the Communards were busy using explosives to destroy buildings in the hope of not just slowing down the enemies advance but as an act of vengeance. If Paris was not to be the workers, then it would belong to no one. Jules Bergeret blew up the Tuilleries Palace and in his despatch boasted of having destroyed the last remaining vestige of Royal power. On 24 May, the Hotel de Ville, the Headquarters of the Commune was put to the torch.

By now most of the leading Communards were either incapacitated, dead or had fled.

The journalist Felix Pyat, who had exhorted the men of Paris to fight to the last through his journal Le Vengeur and had told his colleagues that there could be no more glorious end for him than to die with them on the barricades had since disappeared. Some weeks later he turned up in London. No one could recollect seeing him on any barricade.

Raoul Rigault having resigned as Minister of Police had since appointed himself a Major in the National Guard and was fighting a ferocious rear-guard action in his spiritual home in the Latin Quarter. With the barricades destroyed and his men fighting on in small group she took refuge in a hotel. When the Versaillais surrounded the hotel and threatened to shoot the manager if he did not reveal Rigault's whereabouts, he gave himself up. He was promptly dragged outside and shot three times in the head.

The fighting continued and the leadership of what remained of the Commune fell to the consumptive and dying Charles Delescluze. He had tried his best to try and maintain some order in all the chaos, issuing orders that were largely ignored and trying to respond to the constant demands for more men. These he couldn’t provide so he instead went from barricade to barricade to exhort the men already there to ever greater efforts, but he could offer them no relief for by now more than 200,000 Versailles troops under the command of Marshal MacMahon, and General's Gallifet and Douay were flooding the streets of Paris, a force against which the Communards had no answer.

Upon learning that most of the Communard’s artillery had never even been brought into action Delescluze fell into despair. When Wroblewski, who had been fighting on the Left Bank, reported back to him on the situation there, Delescluze offered him command of what was left of the Communes forces. Wroblewski declined to respond but asked him instead if he could provide him 2,000 good men? Delescluze replied that he could not even find him 200 bad ones.

Despite Delescluze pleading with him to do so Wroblewski refused to take command saying that he would rather die an ordinary soldier. He would in fact escape the carnage and flee France on a Polish passport.

Retiring to his office for the last time, Delescluze penned a hasty letter to his sister:

"I do not wish, and am unable to act as the victim of another defeat. I embrace you a thousand times with all my love. Your memory will be the last that will visit my thoughts before I go to my rest.”

He then issued a final rallying cry to the men and women of the Commune: “Comrades! Time to man the barricades! The hour of Revolutionary War has struck!"

Then dressing for the occasion in top hat and wearing a red sash he left to join the fighters on the nearest barricade and clambering atop it raised his silver topped cane in the air and awaited the bullet that would kill him. It was not long in coming.

By the 28 May it was almost all over but the fighting that remained to be done would be bloody and desperate.

The Prussians had sent 10,000 men to the east of Paris to cut-off any possible escape route for the remaining Communards and so a last stand was to be made in the Pere Lachaise Cemetery.

Again, no attempt had been made to reinforce its walls and the Communards were forced to fight from tombstone to tombstone. It was a desperate and ultimately hopeless situation, and hundreds were killed.

Having run out of ammunition and with nowhere to flee, some 174 survivors, both men and women, were forced to surrender.

Once disarmed they were taken to a wall inside the cemetery and shot.

The last barricade to fall on that fateful day was the on the Rue Ramponeau. The last Communard leader to be killed had been Eugene Varlin who had fought onto the end, captured and beaten he was taken to a nearby garden, and shot - the Paris Commune had ceased to exist.

Following the end of the fighting in the Pere Lachaise Cemetery, Louise Michel went into hiding but she gave herself up a few days later when the Authorities threatened to hang her mother if she did not do so.

At her trial she demanded the death sentence but was instead deported to the Penal Colony of New Caledonia.

Le Semaine Sanglante had cost the Government forces 83 Officers and 794 men killed with some 6,000 wounded.

There is no precise figure for the number of Communards who died in the fighting but there were at least 6,600 recorded burials in the immediate aftermath and the likelihood is the figure was much higher. The executions that took place over the following days also took the lives of another 17,000. Those captured fortunate enough to avoid the bayonet and firing squad were tried for treason and some 40,000 were imprisoned, deported or hanged.

The first great experiment in Working Class Government had ended in the most appalling bloodshed as Frenchman had killed Frenchman while their Prussian conquerors looked on with a disdainful astonishment.

Writing at the time Karl Marx declared the Communards to have stormed Heaven; but they had merely descended into Hell.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous

Share this post: