The Dambusters

Posted on 12th June 2021

On the night of 16 May 1943, three Lancaster Bombers of the Royal Air Force took off from Scampton Airfield in Lincolnshire, the first wave of what would be one of the most daring raids of World War Two.

Regardless of the increased presence of American Forces in Britain and the recent victory over the Axis powers in North Africa there was little scope for the Allies to strike at Nazi Germany except from the air. It was felt that unable to engage the German Army on land they could at least disrupt and destroy their capacity to provide for it.

Bomber Command had been sporadically attacking industrial targets in Germany since May 1940 but with the arrival of the United States Army Air Force in England in mid-1942 the bombing had intensified and now formed part of a strategic plan to systematically destroy Germany’s industrial base but high altitude bombing particularly at night was notoriously inaccurate and in truth the damage done to infrastructure was often negligible.le.

Barnes Wallis, a leading engineer working for the Vickers Aircraft Company was intrigued by the concept of strategic bombing as a means of bringing the war to an end and had even penned a paper on how it could be achieved more effectively placing his emphasis on the destruction of the enemy’s power supply – industry could not after all function without the electricity required to turn its wheels: “If their paralysis can be accomplished they offer a means of rendering the enemy utterly incapable of prosecuting the war.”

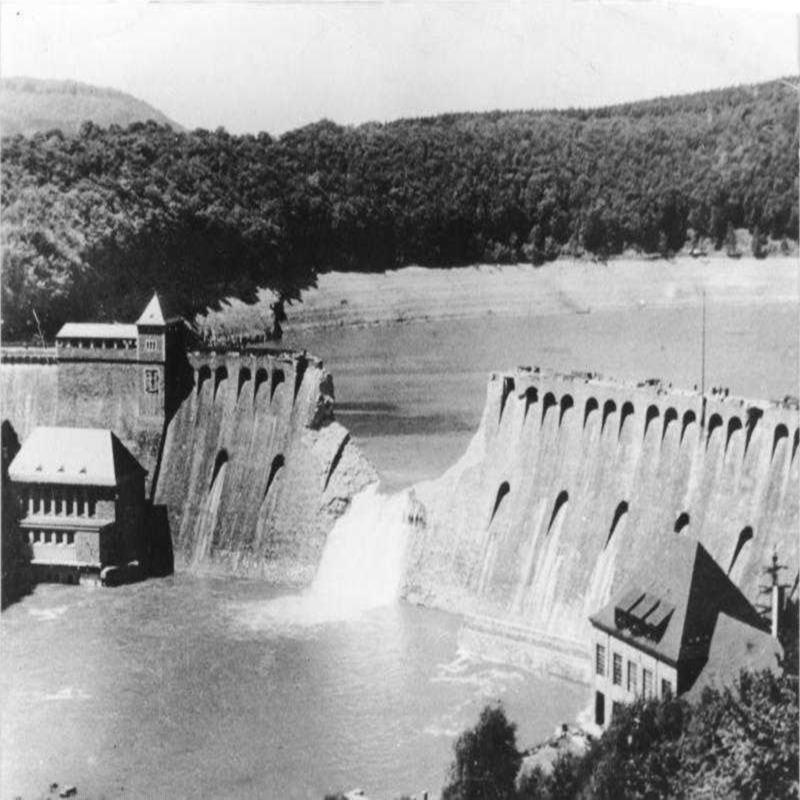

He proposed an attack on the dams in the Ruhr Valley – if these could be destroyed then he believed German industry would grind to a halt.

Wallis’s first idea was for a ten-ton super-bomb to be dropped from an altitude of 40,000 feet but with the bomb having to land within 50 feet of its target to be effective it didn’t overcome the problem of inaccuracy from high altitude and in any case the plane had not yet been built that could deliver it. This didn’t deter Wallis who declared that he would design the plane required, he even had a name for it – the Victory Bomber.

The idea of building a super plane to carry his super bomb was dismissed out of hand and many considered him a fantasist but his concept of destroying the Ruhr Dams remained strategically sound and had the approval of the Head of Bomber Command Air Marshal Arthur Harris, a firm believer that air power alone could win the war – if that is, a way could be found.

The possibility of a torpedo attack had already been pre-empted by the Germans who had strung nets across the approach to the dams protecting them but by mid-1942 Wallis was already experimenting with the idea of using a bomb that could skip across the water.

The Bouncing Bomb, as it became known weighed 9,250 pounds of which 6,000 pounds were high explosive and was to be dropped spinning backwards but designed to spin forwards upon impact making it slide down the dam wall and sink to a depth of 30 feet before exploding causing a catastrophic breach that would then flood much of the surrounding countryside. Its design was similar to the depth charges being used against the U-Boat in the Battle of the Atlantic.

Experiments continued for the rest of the year first using models in controlled conditions, then the successful breaching of a disused dam in Wales, before in January 1943 full-scale trials were carried out at Chesil Beach in Dorset.

The trials had had been positive, but any successful attack would require precision night time bombing carried out at dangerously low altitudes, flying that had rarely yet been seen in aerial warfare. The pilots required to carry out such an attack would have to be the best available but even so would be subject to months of the most intensive training.

Similarly, the man appointed to command the raid would have to be one who had both already proven that he could perform beyond the call of duty and was a leader of men.

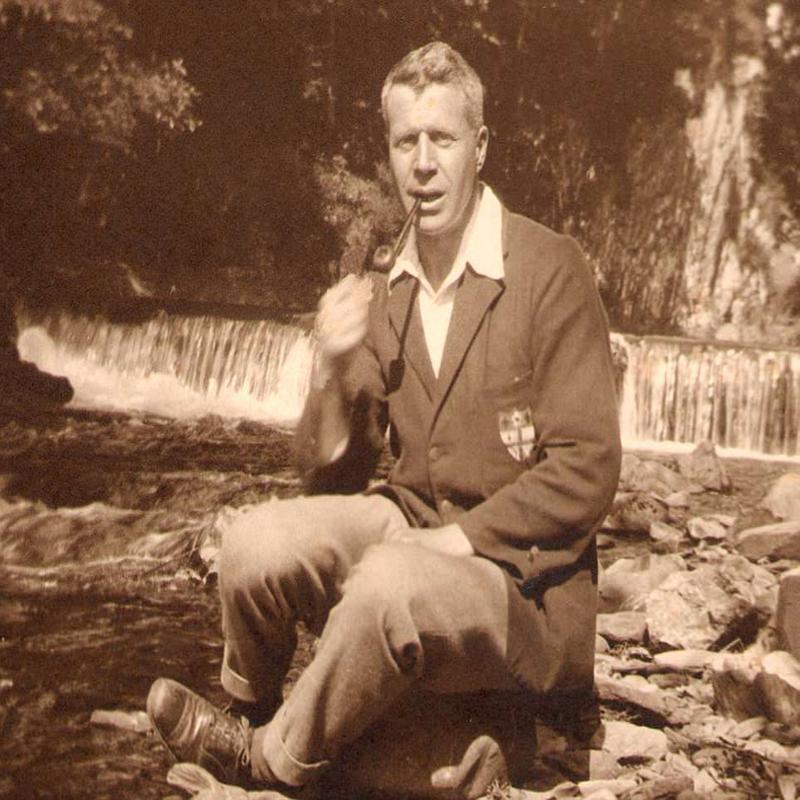

At just 24 years of age Wing-Commander Guy Gibson had already been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Distinguished Service Order and had flown more than 170 combat missions both in bombing raids over Germany and as a night fighter pilot during the Battle of Britain.

Considered a flyer of outstanding ability and unwavering commitment and courage he had the admiration and respect of his superiors if not always the love and affection of the men who served under him especially Ground Crew many of whom considered him condescending towards them.

Unlike most of those in Britain’s ‘Citizen’ Armed Forces, Gibson was a professional who had been in the Royal Air Force since leaving school in 1936 and was by no means an unwilling warrior. He was proud of his abilities and was determined to put them to the test as often as possible, preferably against the enemy.

Gibson was between operations and preparing to go on leave when on 18 March 1943, he was recalled to duty and informed that he was to command Operation Chastise – the bombing of the Ruhr Valley Dams. It was a request not an order, but it was one he was never likely to decline.

Such was the respect he was held that he was permitted to hand-pick the Air Crew for the newly formed 617 Squadron the only precondition that given the hazardous nature of the mission they all voluntarily agree to participate. Arriving at RAF Scampton on 21 March 1943, he got to work right away training his Air Crew hard, criticising those he believed were under performing and even dismissing ones he considered not up to the job. Indeed, some were driven to such pains of anguish that they departed of their own accord – but the training was necessary.

Gibson’s personality also did little to lighten the mood, he was not given to humour, did little to court popularity, and rarely socialised spending more time with his Labrador dog Nigger than he did with his men. Yet, if his manner was less than cordial it didn’t matter, and if the men grumbled it was because they were being worked hard and not told why for the utmost secrecy was maintained throughout and most of the Air Crew remained unaware of their destination until the night of their departure.

Flying to their destination at night barely 100 feet from the ground to avoid radar detection they would drop to 60 feet upon reaching the target making their approach at 240 mph, and with a special device having been designed to calculate the distance dropping their bomb 425 yards distant from the dam. Any diversion from or variation of this and the bombing run would have to be aborted and tried again.

The primary targets were to be the Mohne, Eder, and Sorpe Dams with the attack being carried out by 19 Lancaster Bombers in three separate formations. The planes would take off in groups of three at ten-minute intervals and would be flying so low that lamps were attached to the undercarriage to light up the sea as they crossed the Channel.

Taking the longer northerly route to attack the Sorpe Dam the 5 planes of Formation 2 were the first to take off and would fare badly: one plane was forced to return to base when it was damaged by enemy flak and lost radio contact, another likewise returned having been fortunate to survive hitting the sea, and two planes were lost with their crews when one was brought down by anti-aircraft fire and another crashed into electricity pylons.

The only remaining Lancaster of Formation 2 piloted by the American Joe McCarthy had been delayed thirty minutes by mechanical problems.

The 9 planes of Formation 1 led by Guy Gibson began leaving Scampton destined for the Mohne Dam at 21.39 but also lost a plane on the outward journey when the Lancaster piloted by Flight-Lieutenant Bill Astell flying below tree top level also struck electricity cables and crashed with the loss of its crew.

Formation 1 arrived over the Mohne Dam at 00.56 with Gibson making the first bombing run but despite successfully dropping his bomb it detonated prematurely short of the target.

The second plane to attack piloted by Flight-Lieutenant Johnny Hopgood had already been severely damaged by flak when caught in the explosion of its own bomb it burst into flames and began to career out of control. Hopgood struggled to keep his plane in the air and managed to gain enough altitude for three of his crew to bail out. The plane crashed soon after and Hopgood was killed but the survivors would long remember his courage.

Witnessing the tragic loss of Hopgood and so many of his crew Gibson remained over the Mohne flying low to draw off enemy flak from those still to make their bombing runs of which three more were necessary before the Dam was finally breached.

Gibson remained just long enough to be certain no further bombing runs were required before leading those who hadn’t yet dropped their bomb to attack the Eder Dam. Not as strongly defended as the Mohne, the Eder Dam was however shrouded in a fog that was getting thicker with the passing of every minute and in the poor visibility numerous bombing runs had to be aborted and Gibson was close to abandoning the attempt before the Dam was finally breached.

In the meantime, Joe McCarthy had arrived over the Sorpe Dam alone, the Reserve Formation, one of which had already been shot down, was sent to support him. With a Church steeple hindering their approach there was little time for the Bomb Aimer to correct the height and distance before the plane had to pull up to avoid the hillsides beyond with any quick turn likely to cause the wing to hit the water and bring the plane down.

It wasn’t until the tenth run that a bomb was finally dropped but despite hitting the Dam it did only minimal damage.

The return journey to England was no less hazardous than the raid itself with the already damaged Lancaster’s particularly vulnerable to the by now forewarned anti-aircraft batteries.

One of the Lancaster’s hit repeatedly by enemy flak was that flown by Henry Maudslay, who at just 21 years of age was the youngest of the pilots involved. He had been fortunate when flying alongside Bill Astell he barely avoided the electricity cables that had caused his plane to crash but had nonetheless been considerably shot-up and so shaken that it prompted Gibson to ask if he could continue. Maudslay replied that he could handle it. Shortly after his plane battered and slowed was brought down by enemy fire over Holland killing its entire crew.

Squadron Leader Henry ‘Dinghy’ Young (he’d earned his nickname from being plucked so many times from the water) and his crew were lost when their plane crashed into the North Sea.

The first Lancaster arrived back at Scampton at 03.11, with Guy Gibson following an hour later.

Despite positive reports from Gibson and others the success of the operation remained uncertain, but its cost quickly became apparent; of the 19 Lancaster Bombers that set out 8 failed to return with the deaths of 53 airmen and 3 captured after bailing out. Of those who died 13 were Canadian and 2 Australian. Barnes Wallis was visibly shaken by the loss of life.

Casualties on the ground had also been high and with tragic consequences, of the 2,000 or so people who died more than half are believed to have been slave labourers and prisoners-of-war including 526 Russian women in the town of Nuheim Husten.

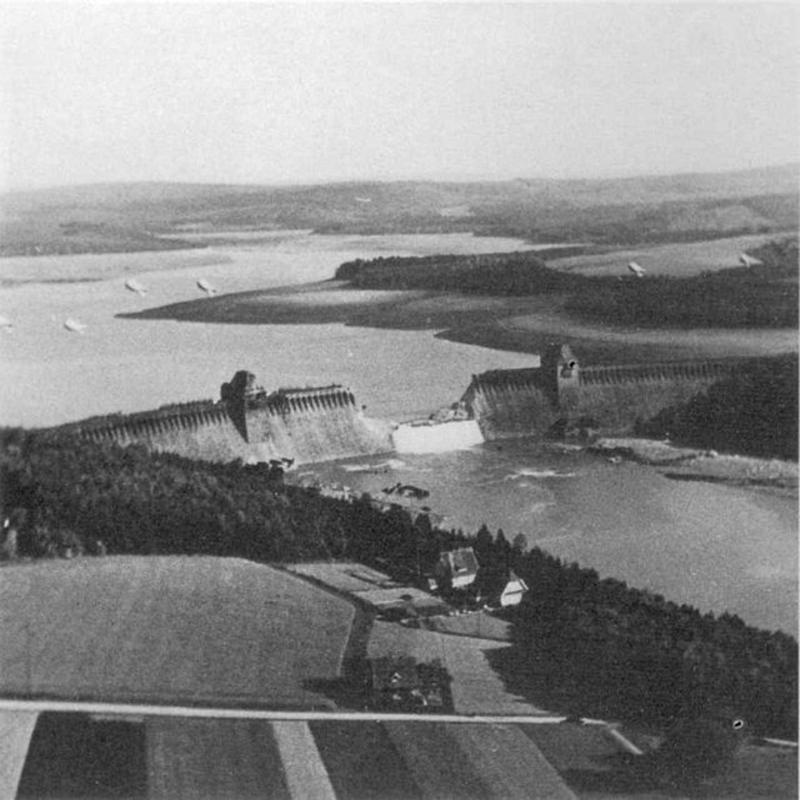

Reconnaissance carried out the following day found the Mohne and Eder Dams partially destroyed and vast swathes of the surrounding countryside flooded to tree top level but the damage assessment was not as encouraging as first thought.

In the Ruhr Valley 25 bridges had been brought down and 11 industrial facilities destroyed with a further 114 seriously damaged but despite the Nazi Minister of Munitions Albert Speer acknowledging the audacity of the raid and admitting that it could have irrevocably set back the production of German war materiel much of the damage was repaired over the following six weeks and production was back to pre-raid levels within three months.

Nonetheless, the Dambuster Raid, as it soon became known, provided a great propaganda coup for Britain and her Allies at a dark time of a war with no end in sight.

More than 30 of the Air Crew were invited to Buckingham Palace to receive medals from the King with Guy Gibson awarded the Victoria Cross, not for leading the raid but for remaining over the Mohne Dam after his bombing run to deflect enemy anti-aircraft fire from those still to do so.

Guy Gibson became a national hero and was to accompany Prime Minister Winston Churchill on a number of high profile and much publicised official visits, but he remained determined to return to active service as soon as possible.

Described by Barnes Wallis as a warrior so valiant he almost courted death Guy Gibson was killed on 19 September 1944, when his Mosquito Bomber crashed on its way back from a pathfinder raid over Germany near the town of Steenbergen in Holland, possibly as the result of mechanical failure.

His death was kept a secret from the British people and not formally announced until January 1945.

Share this post: