The Death of Amy Robsart

Posted on 2nd March 2023

Amy Robsart was the cause, deliberately or otherwise, of a great scandal in the early years of Elizabeth I’s reign that would curtail the ambitions of a man many feared not only had the keys to the Queen’s heart but also her bedchamber and would use both with the aim of becoming King.

She was the daughter of a wealthy Norfolk farmer and wool merchant who in 1560, just shy of her eighteenth birthday married Robert Dudley the third surviving son of the Duke of Northumberland, one of the most powerful men in England after the young King Edward VI. It was a good marriage with both family’s wealthy and influential while Amy possessed a youthful beauty that appealed greatly to the amorous young Robert, a fact he wasn’t shy in sharing causing William Cecil, later the Queen’s Chief Minister who was a guest at the wedding to remark – this is a carnal marriage and marriages of physical desire begin in happiness and end in grief. He was not wrong for the young Lord Robert had an eye not just for beauty but for power and it was the latter that proved the greater aphrodisiac.

Many soon came to suspect that their new Queen was more than just grateful to the handsome and dashing Lord Robert and that they were in fact lovers for she not only insisted upon his presence at Court but made him her dance partner of choice and showered him with gifts, estates in Yorkshire, a mansion at Kew, and a licence to export cloth free of taxation worth thousands of pounds. She also provided him with rooms at the Royal Palace adjacent to her own.

The Queen’s Council headed by William Cecil, Lord Burghley, were eager that Elizabeth be married and provide an heir as soon as possible but not if her preferred choice was the arrogant, ambitious, and heartily disliked Robert Dudley. But it was clear to all who witnessed them together that she had eyes for no other. The rumours only increased when she appointed him her Master of Horse and thereby one of the few people who could legitimately touch her.

In April 1559, the Spanish Ambassador wrote to Philip II in Spain.

“Lord Robert has come so much into favour that he does whatever he likes with affairs, and it is even said that Her Majesty visits him in his chambers day and night. People talk of this so freely that they go so far as to say that his wife has a malady of the breasts, and the Queen is only waiting for her to die to marry Lord Robert.”

The Queen’s fondness for Lord Robert was understandable, he had not only been a good friend but was described at the time as being “splendid in appearance with a promptness of energy and devotion” that was striking.

For those who fretted over the Queen’s future choice of husband the fact that Robert Dudley was already married was a Godsend. Her Council knew that with the experience of her sister fresh in the mind she would not force divorce upon him, but they were also aware that she was seriously ill and not expected to live long. Were she to die then there would be nothing to prevent the Queen from marrying the man she danced with, rode out with, and as many believed was sleeping with.

While rumour and speculation stalked the corridors of the Royal Court, Amy remained alone at the family home, Cumnor Manor in Oxfordshire aware of the gossip and neglected by her husband. As if the humiliation felt by the wronged woman were not enough, she lived constantly in pain at a time when no remedy for her ills existed. The doctors could do nothing and her prayers alone it seemed were not enough.

Early on 8 September 1560, Amy gave her servants permission to attend a fair at nearby Abingdon leaving her alone in the house. Upon their return later that night they found their mistress lying at the bottom of the stair’s dead from a broken neck.

The news of Lady Dudley’s death sent shockwaves through the Royal Court not because it was unexpected but because of its timing and its circumstances. The Lord Robert was now free to marry the Queen, and many feared an announcement to that effect – they could not have been more wrong.

Precious of her image Elizabeth would not allow her reign to be marred by scandal and so regardless of her personal feelings Dudley was banished from Court and an Inquest ordered. He would not be permitted to return or to resume his duties until or before he was entirely cleared of any involvement in his wife’s death.

Lord Robert was no less determined to control the outcome of the Inquest and sent his man Thomas Blount to investigate and report back but few of those he spoke to were willing to commit to what had occurred. Amy’s maidservant Mrs Picto declared she had died neither by her own hand or that of another but that her mistress was a good, virtuous and gentlewoman who would daily pray upon her knees for God to deliver her from her desperation. But when Blount suggested she may have had an ‘evil toy’ (suicide) in her mind Picto replied, that is no good Mr Blount, do not judge so of my words. If you should so gather from, then I am sorry I said so much.

It was not possible however to prevent what was being said elsewhere. William Cecil for example, let it be known he thought poison may have been the cause while Ambassadors abroad were encouraged to spread the rumour that there was more to Lady Dudley’s death than met the eye. Even the young Mary, Queen of Scots was inclined to write:

“The Queen of England is going to marry her horse-keeper who has killed his wife to make room for her."

The common opinion was that Robert Dudley had been involved in his wife’s death in some way or another. After all, the staircase she was found at the bottom of had only eight low steps hardly enough to break someone’s neck unless pushed, of course. While had it been suicide then it as unusual method to choose given there was no guarantee of death.

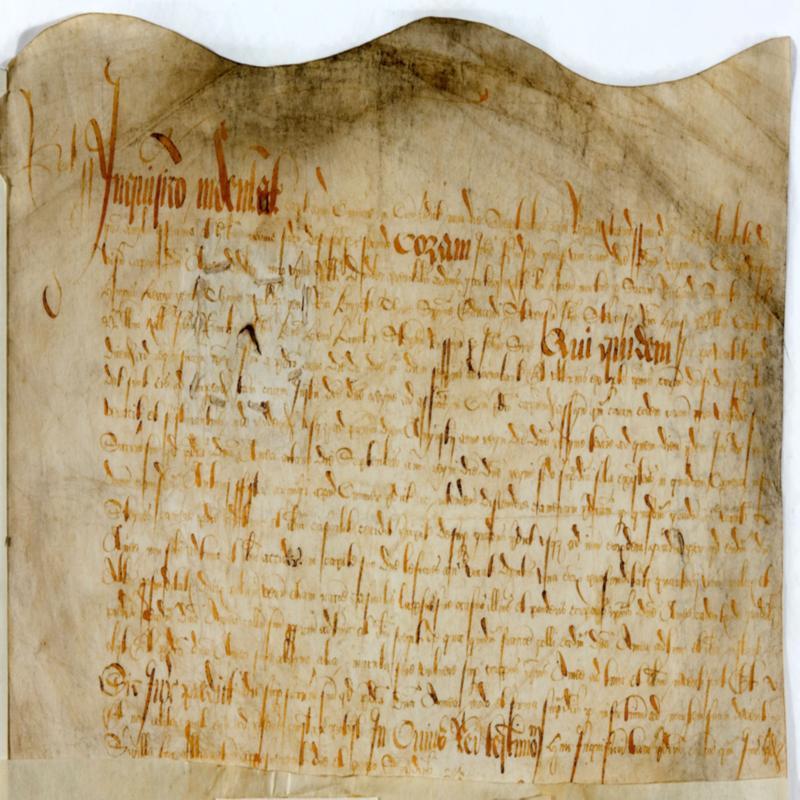

The coroner’s verdict was not delivered at the Local Assizes until 1 August, 1561, almost a full year after Amy’s death:

(The) jurors say under oath that the aforesaid Lady Amy on 8 September in the aforesaid second year of the reign of the said lady queen, being alone in a certain chamber in the aforesaid Cumnor, and intending to descend the aforesaid chamber by way of certain steps of the aforesaid chamber there and then accidentally fell precipitously down the aforesaid steps to the very bottom of the same steps, through which the same Lady Amy there and then sustained not only two injuries to her head – one of which was a quarter of an inch deep and the other two inches deep – but truly also, by reason of the accidental injury or of that fall and of Lady Amy’s own body weight falling down the aforesaid stairs, the same Lady Amy there and then broke her own neck, on account of which certain fracture of the neck the same Lady Amy there and then died instantly; and the aforesaid Lady Amy was found there and then without any other mark or wound on her body; and thus the jurors say on their oath that the aforesaid Lady Amy in the manner and form aforesaid by misfortune came to her death and not otherwise.

Robert Dudley had been exonerated, and he was a relieved man. He wrote to Blount: “The verdict doth very much quiet and satisfy me.”

Doubts persisted but he was nonetheless re-admitted into the Queen’s presence where eager to resume his courtship of her he proposed time and again but Elizabeth while keeping him close to her heart was wise enough to keep him distant from her body politic. Indeed, so unlikely had their union become that in 1563 she proposed him as a future husband for Mary, Queen of Scots.

Loyal to those who served her well Elizabeth did not in turn relinquish their affections easily and so when on 21 September 1578, Dudley married Lettice Knollys, widow of the recently deceased Earl of Essex, he kept it secret from her fearing her wrath. But he was unable to silence the rumours that he had murdered the Earl of Essex to steal his wife just as he had many years earlier killed his own wife in the hope of marrying the Queen. When Elizabeth became aware of the hearsay, she banished Dudley and his new wife from the Court, the latter for good.

Elizabeth would relent in time and Dudley would again take up residence in the chambers next to hers becoming in due course the impresario of her public image while despite the ravages of time, the effects of gout, and a less than impressive military record she would appoint him to command the land forces during the crisis of the Spanish Armada. It was he who orchestrated her famous address to the troops stationed at Tilbury.

The mysterious death of his wife had many years before scuppered his chances of ever becoming King and the rumours of his involvement persisted throughout his life, but the people at least would come to hold him in high regard referring to him affectionately as Robin. Those of the Royal Court were never so magnanimous.

Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester died on September 4, 1588, aged 56. It was said that when Elizabeth died thirteen years later, she did so while she clutched a miniature of him in her right hand.

Tagged as: Tudor & Stuart, Women

Share this post: