The Dreyfus Affair

Posted on 1st July 2021

The Dreyfus Affair divided French society in ways unseen since the Revolution; it saw the emergence of a virulent but previously latent anti-Semitism, set Left against Right, and poisoned the body politic for decades to come. It laid bare French pretensions to homogeneity and the controversy refuses to go away resonating in France even to this day.

Alfred Dreyfus was born on 9 October 1859, in the city of Mulhouse in the region of Alsace bordering Germany. His father, Raphael, was a successful Jewish textile manufacturer who conducted his business affairs in Yiddish and spoke German as a first language as indeed did most of Alfred’s eight siblings; so though the family fled to Paris at the end of the Franco-Prussian War and the German annexation of Alsace it seemed to many they were barely French at all.

That doubt could ever be cast upon his patriotism never entered the mind of the young Alfred who had determined upon a military career early burning with desire as he was to avenge the humiliation of 1870-71.

Although Jews had been fully assimilated into French society since the time of the Revolution to many, they remained an alien presence in the country who were not to be trusted. Anti-Semitism was rife in the country if rarely spoken of and there were few among Dreyfus’s fellow Officers unaware of his Jewish background.

By 1894, he had risen to the rank of Captain of Artillery and was highly regarded as a devoted and efficient Officer whose diligence and hard work earned its reward when he was assigned to the General Staff. His career appeared to be on an upward curve, but all this was soon to change.

In September 1894, Marie Bastian, a French cleaner at the German Embassy who was paid to rummage through the rubbish of the ‘enemy’ retrieved a bordereau or list, from the waste-paper basket of Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen, the German Military Attache.

Taken to Major Hubert-Joseph Henry of French Counter-Intelligence the scraps of paper though faint, torn in two and partially burned were able to be pieced together and appeared to indicate the willingness on the part of a French Artillery Officer on the General Staff to sell secrets. It began: “Being without information as to whether you desire to see me, I send you nevertheless monsieur, some interesting information.” It went onto discuss the development of the new long-recoil French field gun, the testing of which had been held in the utmost secrecy and the army’s future long-term strategic plans: “This document is exceedingly difficult to get hold of, and I can have it at my disposal only for a very few days. The Minister of War has distributed a certain number of copies among the corps who are responsible for them.

Each Officer holding a copy is required to return it after manoeuvres.

Therefore, if you glean from it whatever interests you, and let me have it again as soon as possible, I will manage to obtain possession of it. Unless you will prefer I have it copied.”

D.

Despite its obvious significance Henry did not report it or take it to a higher authority for several days. When he eventually did so and a formal investigation was ordered suspicion immediately fell upon the Jew Dreyfus, the German from Alsace.

Despite the fact that there was no firm evidence to implicate Dreyfus in the writing of the bordereau other than the signature ‘D’ and the implausibility that a man engaged in espionage would seek to identify himself the French Minister of War Auguste Mercier ordered the case be resolved swiftly.

So regardless of a lack of motive and Dreyfus’s oft expressed patriotism the investigation into his activities would continue and there were few it seemed within the army who doubted his guilt. He was after all a Jew, a man of an alien race that felt no ties of loyalty to the country that gave him succour.

The army believed that they had unearthed the culprit, or at least the man that would take the blame, but nevertheless they at first trod cautiously as they sought the evidence that would secure a conviction. In the meantime, Dreyfus was not informed that he was under investigation until 9 October and even then, guardedly. He took the news calmly perhaps believing that his name had simply fallen within the parameters of a general inquiry.

Not long after this the facts of the case were leaked to the press which rounded on Dreyfus condemning him in the Court of Public opinion long before he was convicted in a Court of Law.

On 15 October, during a meeting with General Mercier he was curtly informed that he was under arrest for espionage and was to be charged with treason. It was expected that he would admit his guilt but instead he denied everything. Then, presented with a loaded revolver he declined to use it.

Although the evidence against him was flimsy and circumstantial at best (experts could not even agree that the bordereau had been written in his hand) there were all too many people willing to believe and indeed wanted him to be guilty for considered to be arrogant aloof Dreyfus had never been popular with his fellow Officers. He was also personally rich which caused a great deal of resentment.

On 28 November, before he came to trial General Mercier provided an interview to the press in which he openly declared Dreyfus to be guilty of betraying his country beyond any reasonable doubt.

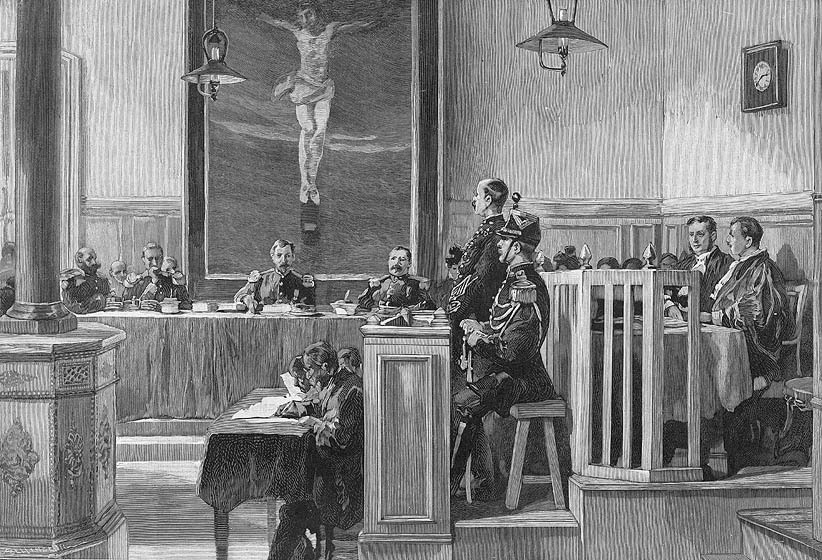

On 22 December 1894, Captain Alfred Dreyfus was brought before a Military Tribunal to face Court Martial. The trial was a sham, the evidence against him contrived but the verdict never in doubt. He was found guilty of colluding with a foreign power and sentenced to life imprisonment.

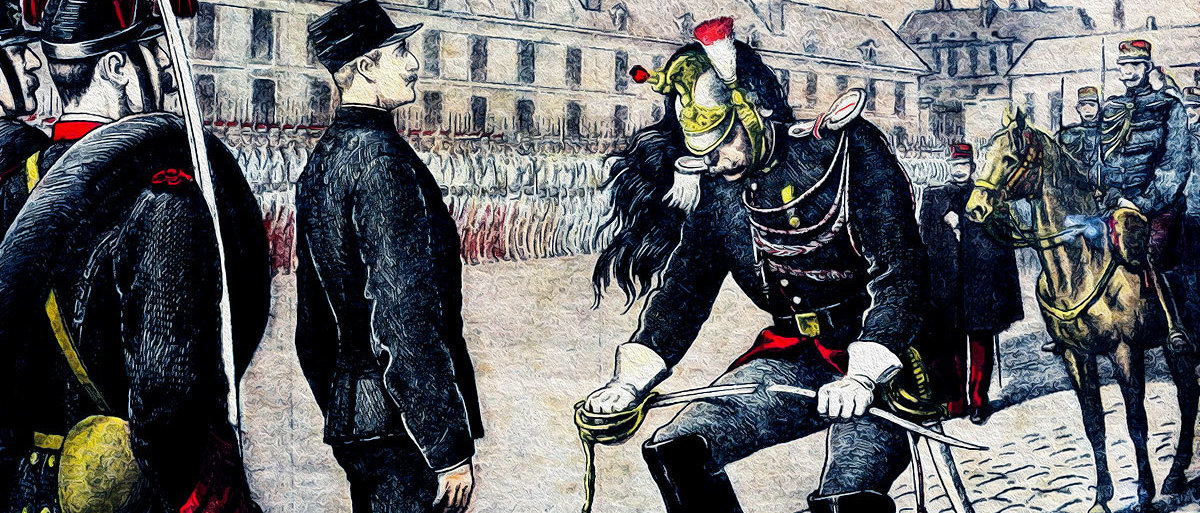

On 5 January 1895, he endured the humiliating ordeal of being publicly stripped of his rank with the epaulettes torn from his shoulders and his sword snapped before his eyes. It was later reported that just prior to this he had admitted his guilt – it was also a lie.

On 15 February he was transported to serve a life sentence on the old penal colony of Devil’s Island in French Guyana. Besides the guards he was its only inhabitant. It had been re-opened especially for him.

As far as the Army was concerned that was that an embarrassing scandal had been averted.

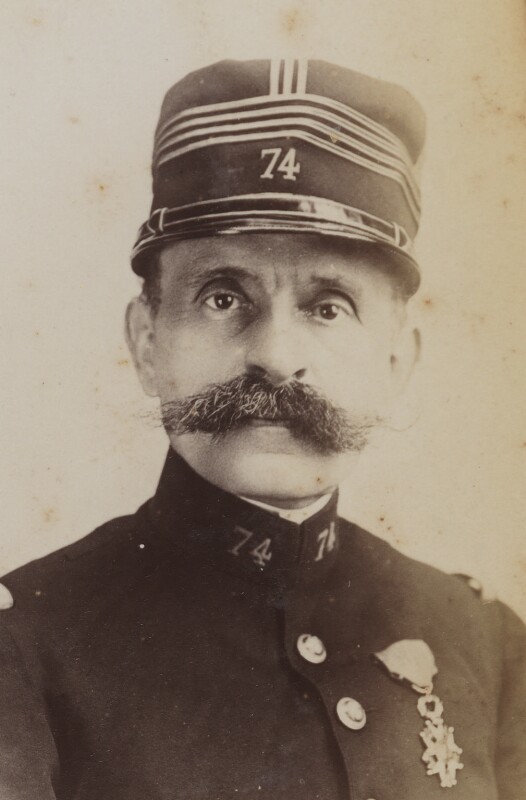

In April 1896, Lieutenant-Colonel Georges Picquart, who had recently been appointed Chief of Army Intelligence, discovered that the bordereau had in fact been written by an Officer of Hungarian descent, Major Ferdinand Wilsan Esterhasy. Despite being a well-known anti-Semite Picquart was an honest and patriotic man who wanted to see the traitor punished not an innocent man who had become the victim of a cover-up and the convenient scapegoat for a fevered public imagination.

Bringing this to the attention of his superiors he was warned not to proceed further with such accusations but refused to let it lie only to find his further investigations impeded at every turn by Major Hubert Henry, who was a close friend of Esterhasy’s and whom it would transpire had forged the documents that had secured Dreyfus’s conviction.

Unable to persuade Picquart to cease his investigations in December 1896, he was relieved of his duties and sent to serve in Tunisia but it was too late, the evidence he had unearthed had already been made public and it very quickly sparked a national debate.

The man, who now found himself at the centre of the case Major Esterhasy was not one to inspire confidence. He was a drunk, an inveterate liar and a rabid anti-Semite, though this did not prevent him from begging Jewish financiers for money when he needed it, and he did. He had squandered the family fortune in the gambling houses and brothels of Paris and had done the same with his wife’s dowry. Needless to say, he blamed everyone else for his problems. In particular he blamed the army for thwarting his ambitions.

A fluent German speaker himself he told Schwartzkoppen that he was not only willing to sell military secrets for a price but that the more he paid the more he could have. Indeed, he was willing to betray his country with such alacrity that the Italian Attache Panizzardi, with whom Schwartzkoppen shared the secrets, doubted that he was a French Officer at all, and it had to be arranged for Esterhasy to parade himself before them in full military regalia just to prove he was.

In early 1897, Picquart presented his evidence to Dreyfus’s lawyers. Informed of this and to pre-empt any future proceedings against him Esterhasy demanded a private hearing behind closed doors to clear his name.

The subsequent trial was a sham. One of those on the Military Tribunal was Major Henry who guided them to an acquittal. Esterhasy was then awarded a pension and permitted to retire to England. When news of this leaked out violence broke out in Paris and on the streets of many other major cities.

The Dreyfus Affair had followed hot on the heels of other controversies including the Boulanger Coup-de-Etat and the Panama Canal Scandal and to many it seemed as if the very existence of the French Republic itself was at stake.

It was to be Dreyfus’s older brother Mathieu who would prove the catalyst for his eventual release, however. He had never for a moment doubted his brother’s innocence and carried out his own investigation unpicking the evidence against him in a series of booklets he published.

On 13 January 1898, the famous novelist Emile Zola published his famous J’Accuse, an open letter addressed to the President of the French Republic. In it he condemned the Government and the military for their lies and the subsequent cover up. The investigation he wrote, had been little more than a farce and Dreyfus’s conviction was the result of the dirty Jew obsession that was the scourge of our time. He also named Major Esterhasy as the traitor and that the Army had only cleared him of all charges to save face.

In response to his letter the Authorities tried to have Zola arrested for libel but he fled to England before they could do so. Meanwhile, J’Accuse was re-printed around the world causing a sensation.

Zola’s intervention saw the more liberal press which had at first accepted the verdict at face value begin to express doubts. This was particularly so in the pages of Le Figaro which began to actively campaign on Dreyfus’s behalf but soon ceased when many of its readers threatened to boycott the paper.

Soon prominent left-wing politicians such as Jean Jaures, Leon Blum and even the liberal ex-Mayor of Paris Georges Clemenceau, that paragon of Republican virtues, began to demand a retrial. France was by now firmly divided into two camps – pro-Dreyfus and anti-Dreyfus.

The Army, the Right-Wing Press and the Catholic Church now attacked those who were trying to exonerate Dreyfus as being Freemasons and Radicals. It was all part of a Jewish Conspiracy, they said, to destroy the prestige of the French Army. But despite their best efforts it was becoming evident that a miscarriage of justice had occurred. In April 1899, Dreyfus was granted a second court-martial.

In the meantime, Major Hubert Henry who was under arrest for having forged documents in the case committed suicide in prison. The Defence had lost their key witness so despite the Prosecution earlier admitting to a cover up having occurred Dreyfus was again found guilty but this time mitigating circumstances were taken into account and the sentence was reduced to ten years. France was once again in tumult, would this ghastly affair ever end.

In September 1899, the French President Emile Loubet personally intervened and granted Dreyfus a pardon. This did not exonerate him of the charge of treason, however.

Alfred Dreyfus had suffered terribly during his five years of incarceration on Devil’s Island; he had for the most part been kept in solitary confinement where he was chained to his bed each night and with no one to talk to he had virtually lost his power of speech. The terrible heat made it almost impossible to sleep, he was frequently ill and the bad diet had led to weight loss and seen his teeth fall out. But at least he was now free, even if according to the law he was still guilty.

Emile Zola, who had done so much to bring the Dreyfus Affair to international attention died on 29 September 1902, from carbon monoxide poisoning caused by a blocked chimney. Given the previous attempts on Zola’s life and the divisiveness of the Dreyfus Affair murder cannot be entirely ruled out.

Ferdinand Esterhasy, died n England on 21 May, 1923. He was never brought to account for his treason and was despite all the evidence to the contrary to declare his innocence and decry the on-going Jewish Conspiracy for hounding him.

Alfred Dreyfus wasn’t cleared of all the charges against him and restored to his position in the Army until 1906 and was to go on to serve with distinction in World War One where he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel and later awarded the Legion d’Honneur.

But he had disappointed many of his more radical supporters by first accepting his pardon without demur and then re-joining the army. He refused to play the blame game or join the ranks of the political Left.

He died in Paris on 12 July, 1935, proud of his military service and seemingly oblivious to his notoriety and the great scandal he had been at the centre of.

Tagged as: Modern

Share this post: