The Fall of Singapore

Posted on 15th April 2021

By the early decades of the twentieth century the process of modernisation in Japan undertaken following the Meiji Restoration of 1867 was well underway. She had established diplomatic ties with the other world powers, started the process of industrialisation with Western assistance and financial aid and had begun to adopt Western values and cultural norms. She was eager to establish herself as the major regional power and to that end had worked hard to create a powerful military.

In this the Western powers looking for markets in the Far East and seeing Japan as a curb to Russian territorial ambitions in the region were only too willing to help.

In February 1904, Japan, without a declaration of war attacked the Russian held base of Port Arthur in Manchuria and over the next 18 months decisively defeated her both on land and at sea.

Their victory surprised many and it was the first time that an Asiatic people had defeated a Western power in a major war. She went onto to be part of the Allied Coalition during the Great War mopping up German resistance and seizing their possessions in the Far East.

Japan had proved herself to be a trusted ally of the Western powers, but she also had Imperial ambitions of her own that were ignored at the Versailles Peace Conference which followed the end of the war. She felt that she was not being shown due respect by the Western powers and on 1 September 1923, her weakness was further exposed it seemed when she was hit by one of the most powerful earthquakes ever recorded that devastated much of Tokyo and Yokohama leaving 140,000 people dead. The Western powers rallied to help but it was thought by many in the country that Japan not being able to cope on her own was a national humiliation.

The following year the United States Congress passed the Exclusion Bill that banned any further immigration from Japan. The Bill did not stretch to banning immigration from the European Continent and was viewed as racist and an indication that America at least considered the Japanese inferior.

Always a proud people they were sensitive to what they considered to be the racial slurs levelled at them by arrogant white Imperialists; when their attempt to get a statement of racial equality written into the Covenant of the League of Nations was rejected at the request of Australia and the United States, they took it as a further insult.

In 1929, Japan was badly hit by the global Great Depression and her economic weakness was exposed; following on from the devastating earthquake of six years earlier its sudden reduced status in the world helped fuel an anti-Western backlash as a wave of ultra-nationalist fervour now swept the country.

The one beneficiary of the depression was the military which saw a massive build-up in arms and manpower as peasants from the countryside enlisted in droves to escape the grinding poverty of rural Japan. As their power grew so did their political influence.

On 18 September 1931, following the so-called and probably contrived Mukden Incident, Japan invaded Manchuria quickly overrunning it and creating the Puppet State of Manchukuo where the army quickly established a series of heavy industries virtually independent of Government control. From Manchukuo the Japanese made regular armed incursions into neighbouring China.

On 7 July 1937, a similar incident occurred at the Marco Polo Bridge on the border with China that was to lead to the Second Sino-Japanese War. Few politicians wanted war and sought to limit its scale but factions within the army in particular wanted an all-out conflict.

It would escalate in any case for despite stubborn Chinese resistance their poorly equipped army was unable to stem the Japanese tide and they made rapid progress seizing vast areas of territory as they did so.

.

On 13 December the Imperial Japanese Army captured the Chinese capital of Nanking in what had been a bloody battle that had left 6,000 Japanese and many more Chinese troops dead but it was the massacre that followed that was to shock the world. The Rape of Nanking that may have seen as many as 200,000 civilians murdered was so brutal that even the Nazi regime in Germany felt compelled to condemn it appeared to reinforce the racial stereotype of the Japanese as no better than wild beasts.

By 1940, despite early optimism the Japanese had lost more than 140,000 men killed and become bogged down in China. It was an embarrassment not to have defeated an enemy they considered their racial inferior, and the war was proving a drain on resources. It seemed their ambition to create a South-East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere under Japanese domination might actually unravel on mainland China, a country they could never truly hope to occupy. They began to look elsewhere.

In July 1941, Japanese forces occupied French Indochina and the United States worried by Japanese expansionism demanded their immediate withdrawal. Tensions between Japan and the United States had been growing for many years and negotiations between the two countries had long since stalled.

In August 1941, President Roosevelt imposed economic sanctions and ceased oil exports to Japan. Without American oil Japan was unable to function. It now faced a dilemma, to either curb its Imperial ambitions or go to war to capture the raw materials it needed for itself.

As long as Japan had a civilian Government the chance of a negotiated settlement remained but in October 1940, Prince Fumimoro Konoye resigned as Prime Minister to be replaced by General Hideki Tojo. Negotiations were resumed but plans had already been put in place for war.

At 07.48 on the morning of 7 December 1941, 183 war planes from Japanese Task Force Z under the command of Mitsuo Fuchida attacked the American Pacific Fleet moored at Pearl Harbour in Hawaii. It was a Sunday, and the Americans were utterly unprepared for combat. By the end of a long and bloody day the Battleships Arizona, California, Oklahoma, and West Virginia had been sunk and three others damaged beyond immediate repair, a further 7 ships had also been sunk or damaged, and 188 planes destroyed mostly on the ground. Some 2,459 Americans had been killed for the loss of just 29 Japanese planes and 4 midget submarines. It was a devastating blow but the three American Aircraft Carriers had been at sea during the attack and were missed and the fuel and supply depots remained largely undamaged.

Nevertheless, the Japanese were delighted as far as they were concerned American power in the Pacific had been destroyed. The following day Japanese forces attacked the British colony of Malaya.

Malaya produced 38% of the world’s rubber and 58% of its tin and as a country that possessed few raw materials of its own it was a prime target of Japanese war aims. Also, at the tip of the Malay Peninsula lay the Island of Singapore the bastion of British Imperial power in South-East Asia and considered an impregnable fortress. If it were to fall it would be a devastating blow to the prestige of the British Empire.

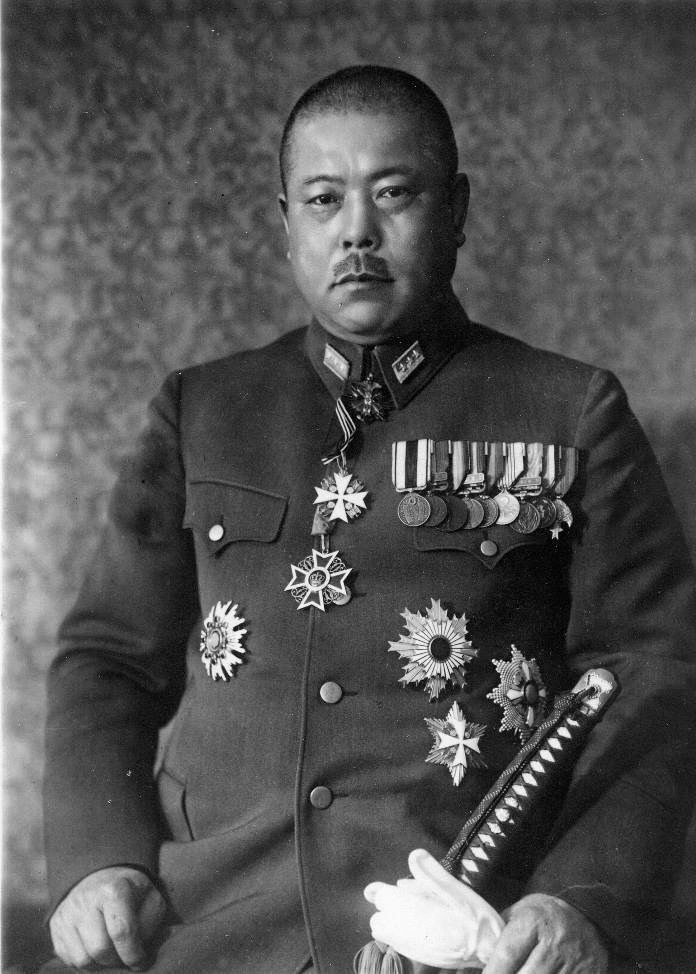

The man in command of the attack upon Malaya was to be General Tomoyuki Yamashita.

He had been born in the village of Osugi on 8 November 1885 who the son of a doctor was not of the aristocratic background of many senior Officers in the Japanese Army but a prodigiously hard worker he nevertheless progressed rapidly through its ranks, but he was considered unconventional not only in his military tactics but also in his political thinking and his maverick standing ensured that he was not entirely trusted.

Like many Officers in the Japanese Army, he was politically active and a member of the Imperial Way Faction or Kodoha that looked back to a pre-Westernised Japan based on devotion to the Emperor and a belief in Bushido and the code of the Samurai. It was a faction made up of mostly junior Officers from modest rural backgrounds similar to his own.

Even though the Kodoha was militarist and expansionist in its thinking Yamashita was willing to express the view that Japan should withdraw from China and remain on friendly terms with the Western powers. He was then in many respects an outsider.

After various roles as a military attaché which included postings to Europe, he was appointed Commander of the 25th Army on 6 November 1941.

The British Commander at Singapore was Lieutenant-General Arthur Percival.

He had been born in Aspenden, Hertfordshire on 26 December 1887, the son of a Land Agent who after attending Public School enlisted in the Army upon the outbreak of the Great War as a private soldier. His background however saw him commissioned as an Officer within weeks of his enlistment.

Personally courageous he had a good war being awarded both the Croix de Guerre and the Military Cross and was promoted to Major and later served in Ireland where he was accused by the Irish Republican Army of running a torture squad. Indeed, so brutal was his behaviour during the Anglo-Irish War that the I.R.A twice tried to murder him.

Tall and slender with a weak jaw he was not a figure who immediately instilled confidence in his men, but he was good at his job. After serving as a Staff Officer, he was promoted to Lieutenant-General and appointed General Officer Commanding Malaya in April 1941.

Japanese aggression in South-East Asia which they considered to be their sphere of influence was not unexpected, but the British had nothing but contempt for their potential opponents. The Japanese were thought small, physically weak and short-sighted so much so that they couldn’t see in the dark. They were also slavishly obedient and not very bright.

Just a year before the invasion of Malaya, Air Chief Marshal Sir Robert Brooke-Popham, Commander-in-Chief of British Forces in South-East Asia, wrote to Sir Hastings Ismay back in London: “I had a good close-up across the barbed wire where I observed various sub-human specimens dressed in dirty grey uniforms which I was informed were Japanese soldiers. If these represent the average of the Japanese Army I cannot believe they will make an intelligent fighting force.”

He could not have been more wrong, the Japanese Army was well-trained, disciplined and had a great deal of experience fighting in China. This cut little ice with the British who considered the war in China to be one inferior race fighting another.

Nevertheless, on 2 December 1941 the Battleships Repulse and Prince of Wales with a small flotilla of destroyers arrived in Singapore to act as a deterrent to Japanese aggression. General Percival also considered sending troops into Thailand to occupy the Airfield at Singora to prevent it falling into Japanese hands. The plan was shelved because to do so would violate Thai neutrality. General Yamashita was to have no such scruples.

On the morning of 8 December, Yamashita’s Chief of Staff the brutal, fanatical, ambitious, plain-spoken, insubordinate and sometimes brilliant Colonel Masonubu Tsuji, who would later descend into madness and dine on the liver of a downed Allied Airman exalting its virtues and castigating his colleagues for not doing the same, suggested that they should attack at the height of the monsoon because he believed that British soldiers did not like to fight in the rain and were afraid of fog. As a result of his suggestion, Yamashita chose inclement weather during which to launch a series of amphibious landings on the Malayan mainland.

They also landed forces at Songkhla and Pattani in Thailand capturing the Airfield at Singora before travelling overland to attack Malaya from the west.

General Yamashita had decided that there should be no preliminary bombardment to maintain the element of surprise and he had also declined the offer of two further Divisions and would depend upon the two he already had, around 60,000 men, because he did want to limit his speed and manoeuvrability. Indeed, some 12,000 of his men were provided with bicycles so that he could maintain the momentum of the advance. He also had 459 planes, a Naval Task Force in support, and 80 or so light tanks. The British had no tanks as they had been considered unsuitable for jungle warfare.

At midnight on 8 December, the Japanese assaulted Kota Bharu at the same time as planes flying from Singpora attacked British Air Bases in Northern Malaya destroying 80 of the 110 planes while they were still on the ground. The remaining planes were hastily withdrawn to Singapore.

Despite this early success the attack on Kota Bharu was almost a disaster with the 8th Indian Brigade defending Kota Bharu taking a heavy toll of the Japanese who suffered 850 casualties or 15% of their total attacking force and for a time it put in some doubt Yamashita’s strategy of amphibious landings, particularly when ten British Hudson Bombers attacked the invasion force destroying and seriously damaging several the landing craft.

Indeed, the Japanese were struggling to make much headway and the fighting around the beachhead was particularly vicious and often hand-to-hand; but a British counterattack failed to close the beachhead and with the Japanese now spreading out and getting behind the British lines and with reports of other landings further south, a withdrawal was ordered. After further heavy fighting around the Airfield and a dogged rear-guard action Kota Bharu was finally taken.

On 10 December, Japanese forces attacked the major British Air Base at Jitra.

The troops defending the Base were inexperienced Punjabis and in a driving rainstorm, attacked by tanks and with little artillery support they broke and fled. Major-General Murray-Lyon in command had little choice but to abandon Jitra in haste.

He had been both out-fought and out-manoeuvred and the collapse had been so sudden that he had not even had the time to destroy the ammunition dumps and supplies which fell into Japanese hands. The Battle of Jitra had been a disaster for the British and Murray-Lyon was later removed from his command.

In response to the defeat at Jitra, General Percival ordered that all remaining planes in Northern Malaya now be withdrawn to Singapore. British air power in Malaya had quickly been shown to be woefully inadequate and the Royal Air Force equipped mainly with obsolete and slow Brewster Buffaloes were totally out-classed by the Japanese Zero fighter and many of the aircraft were later evacuated to the Dutch East Indies.

Within four days of the initial landings all the British Airfields in Northern Malaya had been captured.

On 9 December, Task Force Z made up of the Battleships Repulse, Prince of Wales and four destroyers set sail from Singapore to attack the Japanese troop transports moored off Kota Bharu.

The Task Force was soon diverted towards Kuantan where it was reported that further landings were taking place. The landings were to prove a hoax but rather than return to Singapore Admiral Tom Phillips in command decided to continue onto Kota Bharu.

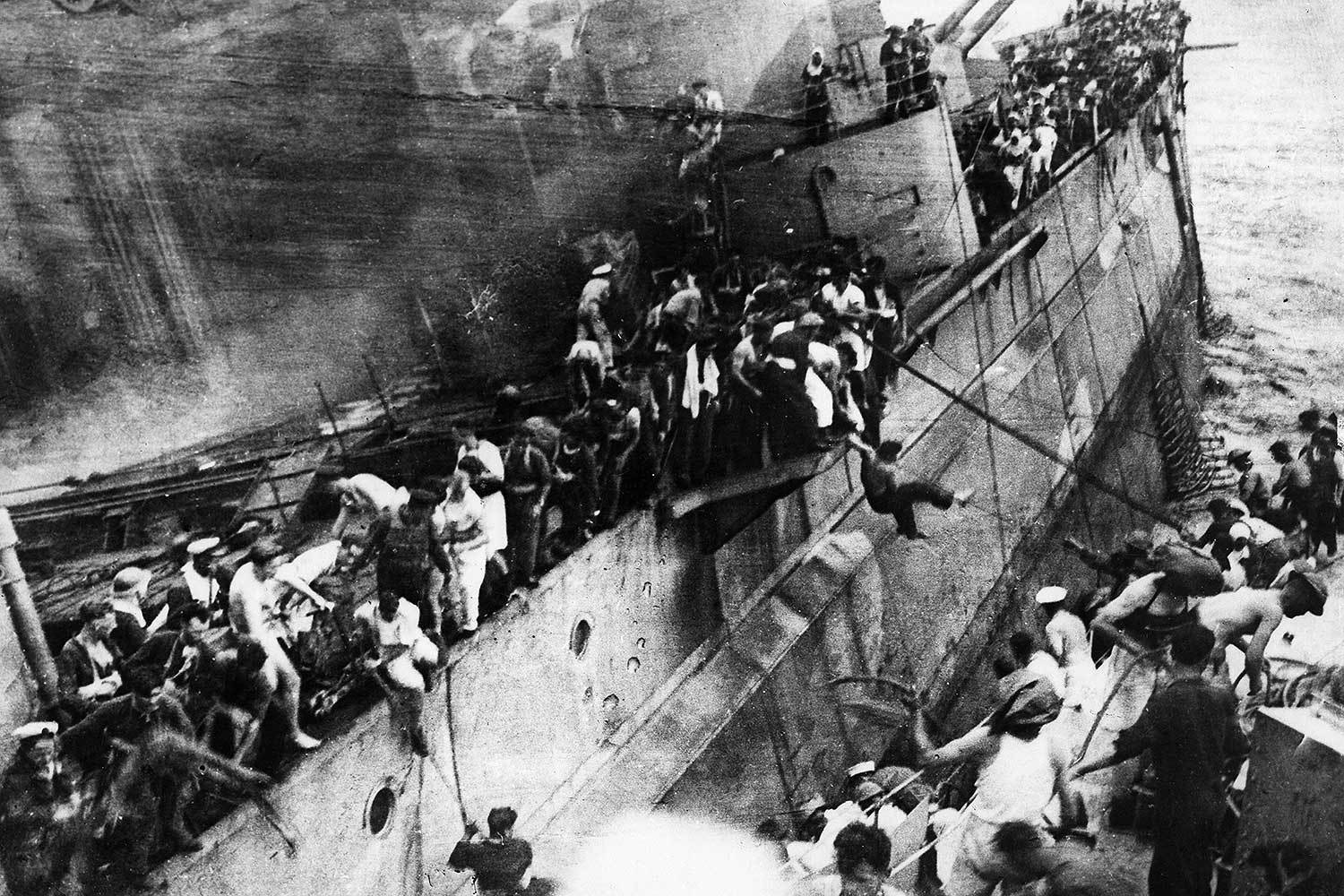

In the meantime, the Task Force had been spotted and at 11.00 am on 10 December, the ships were attacked by bombers and torpedo planes based in Thailand and with no air-cover of their own the ships were sitting targets.

The two Battleships which were the focus of the attack manoeuvred frantically to avoid being hit and were for a time successful but their anti-aircraft guns were to prove wholly ineffective and under sustained assault the end was inevitable. After being hit repeatedly by bombs and torpedoes at 12.33 the Repulse capsized and sank, less than an hour later the Prince of Wales already listing heavily likewise capsized and sank taking Admiral Phillips and the ship’s Captain John Leach with her.

Two of Britain’s premier Battleships had been sunk with the loss of 840 men and at a cost of just 5 Japanese planes and 18 men. It was the first time that capital ships had been destroyed in open sea by air power alone.

The loss of the Repulse and Prince of Wales was a shattering blow to British morale but so rapid was the Japanese advance down the Malay Peninsula that there was little time to dwell on it.

On 17 December after a week of incessant bombing the British abandoned the Island of Penang but only after all Europeans had been evacuated by sea leaving the local population to its fate, an act which caused a great deal of local resentment and was not easily forgotten.

By late December the whole of Northern Malaya had been abandoned and the Japanese continued their advance rapidly down the Malay Peninsula. By 30 December they had reached the town of Kampar but here the British were well dug in and were able to bring their superiority in artillery to bear for the first time in the campaign.

Despite frequent attempts to do so the Japanese were unable to dislodge the British from their positions at Kampar and suffered heavy casualties in the attempt.

The Japanese Commander Takuro Matsui was forced to admit defeat and General Yamashita ordered further amphibious landings to be made to the rear of the British lines and with no forces available to resist the landings the British were forced to withdraw to prepared positions along the Slim River in Central Malaya.

Despite once again being forced to withdraw the British had held up the Japanese advance for six days but the Battle of Kampar was to prove their only victory in the entire Malayan Campaign.

General Yamashita, despite rising casualties and with no tactical reserve was determined to maintain the momentum of his attack. It was vital for his strategy to work that the British were kept off-balance and were not permitted to bring their superior numbers and artillery to bear. Whenever and wherever the British withdrew he would be hot on their heels.

The responsibility for the defence of the Slim River position fell mainly upon the 11th Indian Division with support from elements of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders.

The Indians had already borne much of the fighting and those who remained from previously shattered Brigades were now amalgamated into the 11th Indian Division. They were exhausted, half-starved and their morale was low but even so on 6 January an initial Japanese attack was repulsed at the cost of 60 dead.

Late in the afternoon the Japanese were reinforced by the arrival of Major Shimada’s tank company, and he immediately proposed an audacious night attack. Colonel Ando in command of the Japanese Infantry doubted the success of such a manoeuvre. An attack by tanks at night in the jungle and in the depths of the monsoon could easily see them bogged down and become sitting targets, but Shimada won the argument.

At 03.30 on 7 January, they advanced upon a part of the line held by the Hyderabads who were so shocked to see tanks looming out of the mist and the pouring rain that they panicked and fled. It had taken the Japanese just 15 minutes to shatter the front line. The Punjabis in the second line held for a time but by 06.00 they too had been forced to flee.

The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders resisted the Japanese advance but, in the darkness, and unable to call upon artillery support they soon became separated and found themselves fighting in small isolated groups. Ordered to withdraw, the retreat soon became a rout as many troops simply fled into the jungle where some were to remain until the end of the war in 1945.

General Percival was now forced to replace what remained of the 3rd Indian Corps with the Australian 8th Division under Major-General Gordon Bennett.

Percival was unable to disguise his disappointment at the performance of his often half-trained and inexperienced Indian troops. Their propensity to panic bemused him and appeared to fit the racial stereotype that the Asian could only fight well with a white man alongside him. He expected more from his Australians.

On 9 January the British abandoned the Malayan capital of Kuala Lumpur, the Japanese entered the following day; the new defensive line would now be along the Muar River in the Southern Malay State of Johore.

As the Japanese continued their advance on the Muar River General Bennett laid a trap for them at the Gemas Bridge. Here he waited until the Japanese were almost across before ordering the bridge to be detonated. The Australians, spread out in concealed positions either side of the bridge then raked it artillery and machine-gun fire. It was a massacre as more than 700 Japanese troops were killed many with their guns still strapped to their bicycles.

Yet again the Allies were to be out-flanked however, by an amphibious landing to their rear and by Yamashita’s use of the Scorpion Manoeuvre that saw his troops march through the supposedly impenetrable jungle to attack the Allied forces from the rear. It was a tactic that greatly disheartened the Allied troops and the inexperienced 45th Indian Brigade that opposed the landing was quickly destroyed.

The Australians now facing the prospect of being cut-off fought a desperate four-day rear-guard action. Reaching the bridge at Parit Surong the Australians found it already occupied and in Japanese hands and Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Anderson had little choice but to order each man to make his own way back to Divisional Headquarters as best he could. The wounded would have to be left behind.

Some 135 Australian and Indian wounded were taken prisoner at Parit Surong tied up with barbed wire and bayoneted to death or doused in petrol and set alight. Only two men survived the massacre at Parit Surong by feigning death. The Commander of the Imperial Guards Division responsible Colonel Takuma Nishimura was to be arrested by the Australians after the war and hanged on 11 June 1951.

The Battle of the Muar River had been a bloody and vicious affair that had cost some 5,000 casualties but had yet again ended with Allied troops in full retreat fleeing through the jungle, swamps and rubber plantations of Malaya in a desperate attempt not to fall into Japanese hands.

In his attempt to slow down the Japanese advance General Percival had ordered all bridges destroyed but the tough and ever resourceful Japanese had simply used their own men as bridge props.

Now he had little choice but to abandon Malaya altogether and on 31 January led by a Piper, all troops were withdrawn onto Singapore Island and Percival ordered the causeway that linked the Island across the Johore Straits with mainland Malaya blown up and flooded. He had earlier declined the opportunity to fortify the Straits believing that to do so would be bad for morale.

The Battle for Malaya had ended, the Battle for Singapore was about to begin.

During the fighting for Malaya more than 40,000 British and Commonwealth troops had been taken prisoner much to the disgust of their Japanese captors. To them surrender was the greatest dishonour and to see these tall, strong, healthy looking men willingly laying down their arms in their thousands left them beneath contempt.

The Fortress of Singapore was now to prove anything but impregnable.

Its defences had been neglected over many decades and the trajectory of its formidable 16 inch naval guns that dominated the harbour rendered them virtually ineffective against an assault from the landward side. Indeed, so unprepared was Singapore for a siege that the first time it endured an Air Raid the lights of the city remained on because no one could find out how to switch them off.

General Percival expected Yamashita to assault the Island but rather than try to and second guess him he decided to defend the Island’s entire 70 mile shoreline spreading his forces too thinly and thereby not adequately defending it anywhere. He also had no air cover with the few Hurricane fighters that had been scrambled time and time again to oppose much larger Japanese formations now rendered useless by an Airfield at Kallang so cratered it was no longer operable. He also doubted that he had more than ten days worth of food and ammunition and to add to Percival’s woes he now received a message from the Prime Minister Winston Churchill:

“I want to make it absolutely clear that I expect every inch of ground to be defended, all materiel and defences to be blown up to prevent capture by the enemy, and no question of surrender to be entertained until protracted fighting in the ruins of Singapore City. There must be no thought of saving the troops or sparing the civilian population, the battle must be fought to the bitter end at all costs. Commanders and Senior Officers should die with their troops, the honour of the British Empire and the British Army is at stake.”

Surrender was out of the question.

But General Yamashita also had problems of his own.

He had only 30,000 men under his command, and they were exhausted from their long march and seven weeks of almost constant fighting. His supply lines were stretched to breaking point and his ammunition was so low that his men had been reduced to less than 100 rounds a day. He also knew that the British could still be reinforced by sea.

He could besiege the city and try to starve the British into surrender, but it was questionable as to who would starve first or he could continue the attack. He feared being dragged into a street-by-street fight for the city, a fight he believed he would lose. If he decided to attack it would have to be quick and decisive. He could not sustain a prolonged battle.

The shortest route to Singapore was across the Johore Strait but the landing ground consisted of mangrove swamps that the British considered impassable. As a result, Yamashita knew that it would be weakly defended. It was a risky manoeuvre; his troops would attack in the dark and could easily get bogged down in the swamps making them sitting ducks but it was one Yamashita was willing to take.

On the 5 February he launched a diversionary attack on the east of the Island at Pulau Ubin to confuse Percival before ordering the main assault to begin across the Johore Strait. The attack met little resistance and within an hour of landing Japanese troops had broken through the British lines and were advancing at pace on Singapore City.

Allied troops from across the Island now flooded into Singapore City many having deserted their posts without orders while some of the Australians now rioted looting shops and attacking the local population. Percival appeared to be losing control of the situation and he struggled to restore order as terror now gripped Singapore with civilians cramming the docks looking for a boat out of the city.

The Chinese population aware of events at Nanking were particularly horrified at the prospect of Japanese occupation and news of the atrocities committed during the Malaya Campaign had reached the troops in Singapore.

On 10 February, the Japanese suffered their first setback when another assault across the Johore Strait at Kranji was badly mauled by Australian machine gunners who had also poured oil into the Strait and set it alight. Any advantage was lost however when a series of miscommunications led to the Australians withdrawing contrary to orders.

In the meantime, Japanese air raids had destroyed some of the reservoirs and most of the fuel pipelines into the city and on 11 February, the Japanese captured Bukit Timah and what remained of Singapore’s water supply. The same day Yamashita in an act of bravado demanded that Percival give up his desperate defence and surrender.

Percival’s Senior Officers had also advised him to consider surrender but aware of Churchill’s express order not to do so he demurred and instead he attempted a counterattack but it very quickly petered out and achieved nothing.

Unknown to Percival, Yamashita, who doubted he had the strength to storm the city no less desperate to see an end to the struggle.

It was becoming increasingly evident to everyone of all ranks in Singapore that surrender was inevitable, and a pall of gloom and sense of trepidation invested the city as the frantic work of spiking guns, making materiel inoperable, and destroying official documents got under way.

Firm in his conviction that he had the secret to fighting the Japanese and in the belief that he was too valuable a resource to be taken prisoner, Lieutenant-General Bennett took it upon himself to hand over his Command to his subordinate Brigadier Cecil Callaghan and with a small number of junior Officers commandeered a sampan and fled the city. Arriving back in Australia he was initially praised for his courage and resourcefulness but after the war was accused of deserting his post and made to account for his actions.

At 1.00 pm on 14 February, Japanese troops advanced on the Alexandra Barracks Hospital.

A British Lieutenant carrying a white flag of truce advanced to greet them but was shot and then bayoneted to death. Upon entering the hospital those patients undergoing surgery or could not be moved were likewise bayoneted to death as were many of the doctors and nursing staff who protested at such savagery. The remaining 200 or so walking wounded and members of staff were bound and led away to a nearby industrial complex where they were forced into a series of small badly ventilated rooms where many died overnight.

The following morning the survivors were led outside and hacked to death with machetes, 320 men and 1 woman was killed in the Alexandra Barracks Massacre, only 5 lived to tell the tale.

The day before, Captain Patrick Heenan of the British Indian Army who had been arrested on suspicion of spying for the Japanese and had been taunting his guards that he would soon be free and they all prisoners was taken by the Military Police to the docks where he was executed and his body thrown into the sea.

On the afternoon of 15 February, General Percival and a small entourage drove in a motor car emblazoned with the Union Jack and a White Flag to General Yamashita’s Headquarters at the Ford Motor Factory.

Yamashita was uncertain whether Percival had come to surrender Singapore or demand his own capitulation. And for over an hour Percival obfuscated discussing terms but refusing to mention the word surrender. Eventually Yamashita lost patience and thumping his fist upon the table demanded to know whether he was going to surrender or not?

At 5.15 pm Percival at last agreed to lay down his arms.

It was a remarkable achievement, in just under 9 weeks Japanese forces outnumbered three-to-one had marched over 800 miles, fought 95 battles, repaired 250 bridges and had captured the entire Malay Peninsula and the seemingly Impregnable Fortress of Singapore.

The following day the British Army in Singapore was made to line up to salute General Yamashita as he drove past in his victory parade. The occasion was filmed for propaganda purposes and shown throughout Japan.

Some 30,000 British, 40,000 Indian, 15,000 Australian, and 40,000 Malay and Chinese Militia were taken prisoner in Singapore and the sight of so many men standing to attention and meekly saluting Yamashita as he passed by convinced many in Japan that they could not possibly lose this war against such weak, effeminate and cowardly men. It was the greatest mass surrender in British military history.

Later that night British Officers were provided with brooms and made to sweep the streets of the city. Again, it was filmed for propaganda purposes - the process of humiliating the old Imperial masters had begun.

The prisoners were initially taken to Changi Prison designed to hold only 3,000 inmates on the east of the Island. Many were later transported to do forced labour in Japan, Java, and on the Burma Railroad. More than 17,000 British and Australian prisoners were to die in captivity with even more of those Malays captured falling victim to Japanese brutality.

Of the 40,000 Indian troops taken prisoner around 30,000 were to join the pro-Japanese Indian National Army many of whom served as guards at Changi Prison.

On 18 February, three days after the fall of Singapore the Sook Ching Massacre began with all Chinese males in the city aged between 18 and 50 being rounded up by members of the Kempetai, or Japanese Secret Police. Those who were judged to be anti-Japanese or potential enemies of the Japanese such as lawyers, school teachers, doctors, civil servants or anyone who had a known association with the British were executed. The exact figure of those killed remains unknown but is believed to have been around 50,000.

General Tomoyuki Yamashita was lauded as the Tiger of Malaya and was to go onto command Japanese forces in the Philippines.

Following the American invasion and his surrender of the Philippines he was arrested, charged with war crimes and put on trial for his life. Though it was never proved that he ever ordered atrocities to be committed he was found to be responsible for the actions of the men under his command and sentenced to death. He was hanged at Lugano Prison in Los Banos on 23 February 1946, a little over four years after his great triumph at Singapore.

Lieutenant-General Arthur Percival was imprisoned in a Camp for Senior Officers in Manchuria and though life in the Camp was better than that experienced by his men taken prisoner at Singapore, he was neither beaten nor made to do forced labour the humiliations endured were not dissimilar; he was forced to salute the Japanese flag every day, bow to his guards, made to do menial chores, half-starved and denied medicine.

Following his liberation, the pale and gaunt looking Percival stood behind General Douglas MacArthur aboard the U.S.S Missouri when he took Japan’s formal surrender on 2 September 1945. He then returned to England where he lived a quiet life dying on 31 January 1966, aged 78.

As Winston Churchill had feared the Fall of Singapore was not merely a terrible military defeat it sounded the death knell of the British Empire.

Share this post: